The Tudor Privy Council, C. 1540–1603

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climatic Variability in Sixteenth-Century Europe and Its Social Dimension: a Synthesis

CLIMATIC VARIABILITY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE AND ITS SOCIAL DIMENSION: A SYNTHESIS CHRISTIAN PFISTER', RUDOLF BRAzDIL2 IInstitute afHistory, University a/Bern, Unitobler, CH-3000 Bern 9, Switzerland 2Department a/Geography, Masaryk University, Kotlar8M 2, CZ-61137 Bmo, Czech Republic Abstract. The introductory paper to this special issue of Climatic Change sununarizes the results of an array of studies dealing with the reconstruction of climatic trends and anomalies in sixteenth century Europe and their impact on the natural and the social world. Areas discussed include glacier expansion in the Alps, the frequency of natural hazards (floods in central and southem Europe and stonns on the Dutch North Sea coast), the impact of climate deterioration on grain prices and wine production, and finally, witch-hlllltS. The documentary data used for the reconstruction of seasonal and annual precipitation and temperatures in central Europe (Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic) include narrative sources, several types of proxy data and 32 weather diaries. Results were compared with long-tenn composite tree ring series and tested statistically by cross-correlating series of indices based OIl documentary data from the sixteenth century with those of simulated indices based on instrumental series (1901-1960). It was shown that series of indices can be taken as good substitutes for instrumental measurements. A corresponding set of weighted seasonal and annual series of temperature and precipitation indices for central Europe was computed from series of temperature and precipitation indices for Germany, Switzerland and the Czech Republic, the weights being in proportion to the area of each country. The series of central European indices were then used to assess temperature and precipitation anomalies for the 1901-1960 period using trmlsfer functions obtained from instrumental records. -

Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1986 Basilisks of the Commonwealth: Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553 Christopher Thomas Daly College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Daly, Christopher Thomas, "Basilisks of the Commonwealth: Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553" (1986). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625366. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-y42p-8r81 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BASILISKS OF THE COMMONWEALTH: Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts fcy Christopher T. Daly 1986 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts . s F J i z L s _____________ Author Approved, August 1986 James L. Axtell Dale E. Hoak JamesEL McCord, IjrT DEDICATION To my brother, grandmother, mother and father, with love and respect. iii TABLE OE CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................. v ABSTRACT.......................................... vi INTRODUCTION ...................................... 2 CHAPTER I. THE PROBLEM OE VAGRANCY AND GOVERNMENTAL RESPONSES TO IT, 1485-1553 7 CHAPTER II. -

Robert Greene and the Theatrical Vocabulary of the Early 1590S Alan

Robert Greene and the Theatrical Vocabulary of the Early 1590s Alan C. Dessen [Writing Robert Greene: Essays on England’s First Notorious Professional Writer, ed. Kirk Melnikoff and Edward Gieskes (Aldershot and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008), pp. 25-37.\ Here is a familiar tale found in literary handbooks for much of the twentieth century. Once upon a time in the 1560s and 1570s (the boyhoods of Marlowe, Shakespeare, and Jonson) English drama was in a deplorable state characterized by fourteener couplets, allegory, the heavy hand of didacticism, and touring troupes of players with limited numbers and resources. A first breakthrough came with the building of the first permanent playhouses in the London area in 1576- 77 (The Theatre, The Curtain)--hence an opportunity for stable groups to form so as to develop a repertory of plays and an audience. A decade later the University Wits came down to bring their learning and sophistication to the London desert, so that the heavyhandedness and primitive skills of early 1580s playwrights such as Robert Wilson and predecessors such as Thomas Lupton, George Wapull, and William Wager were superseded by the artistry of Marlowe, Kyd, and Greene. The introduction of blank verse and the suppression of allegory and onstage sermons yielded what Willard Thorp billed in 1928 as "the triumph of realism."1 Theatre and drama historians have picked away at some of these details (in particular, 1576 has lost some of its luster or uniqueness), but the narrative of the University Wits' resuscitation of a moribund English drama has retained its status as received truth. -

Elizabeth I: a Single Female Ruler at a Time When Men Had the Power

GCSE History –British Depth Studies: Elizabethan England c1568-1603 Elizabeth and her Government KEY INDIVIDUALS KEY WORDS Elizabeth I: A single female ruler at a time when men had the power. Was very intelligent but had a difficult Inherit: An heir receives money, property or a title from someone who has died childhood. Treason: Betraying the country you are from, in particular trying to kill or throw the person or people Henry VIII: The monarch of England between 1509 – 1547, he famously broke from Rome and was the first in charge. Head of the Protestant church in England. He had 6 wives and was the father to Mary I, Elizabeth I and Privy council: A group of people, usually noble men or politicians who give advice to a Monarch. Edward VI. Patronage: Someone who has been given the power to control something and gets privileges. Anne Boleyn: Elizabeth I’s mother, Henry broke from Rome to divorce Catherine his previous wife and Succession: When one person follows another in a position, usually gaining the title of the person marry her. She was executed for adultery. before. Edward VI: Henry I third child and his only son. He was King first (1547 -1553)before his older sisters, he Heir: A person legally entitled to someone's property or title after they have died, they continue the was a Protestant and put in place strict rules against Catholicism. work of the person before them. Mary I : Elizabeth’s older sister. She became Queen in 1553-1558 and tried to make England Catholic. -

How the Elizabethans Explained Their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 Justification: How the Elizabethans Explained their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia Christopher Ludden McDaid College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation McDaid, Christopher Ludden, "Justification: How the Elizabethans Explained their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625918. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4bnb-dq93 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Justification: How the Elizabethans Explained Their Invasions of Ireland and Virginia A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fufillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Christopher Ludden McDaid 1994 Approval Sheet This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts r Lucfclen MoEfaid Approved, October 1994 _______________________ ixJLt James Axtell John Sel James Whittenourg ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.............................................. -

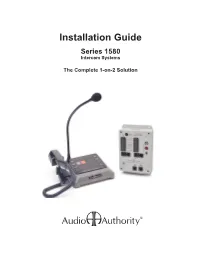

1580 Series Manual

Installation Guide Series 1580 Intercom Systems The Complete 1-on-2 Solution 2048 Mercer Road, Lexington, Kentucky 40511-1071 USA Phone: 859-233-4599 • Fax: 859-233-4510 Customer Toll-Free USA & Canada: 800-322-8346 www.audioauthority.com • [email protected] 2 Contents Introducing Series 1580 Intercom Systems 4 Series 1580 System Components 4 1580S and 1580HS Kits 4 Audio Installation 5 Lane Cable Information 6 Wiring 6 Advertising Messages 7 Traffic Sensors 8 Basic Calibration and Testing 9 Self Setup Mode 9 Troubleshooting Tips 9 Operation 10 Operator Guide 11 Using the 1550A Setup Tool 12 Advanced Calibration and Setup 12 Power User Tips 12 1550A Configuration Example 13 Definitions 14 Appendix 15 WARNINGS • Read these instructions before installing or using this product. • To reduce the risk of fire or electric shock, do not expose components to rain or moisture • This product must be installed by qualified personnel. • Do not expose this unit to excessive heat. • Clean the unit only with a dry or slightly dampened soft cloth. LIABILITY STATEMENT Every effort has been made to ensure that this product is free of defects. Audio Authority® cannot be held liable for the use of this hardware or any direct or indirect consequential damages arising from its use. It is the responsibility of the user of the hardware to check that it is suitable for his/her requirements and that it is installed correctly. All rights are reserved. No parts of this manual may be reproduced or transmitted by any form or means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system without the written consent of the publisher. -

Black British History Tudors & Stuarts Ad 1485 - 1714

A TIMELINE OF BLACK BRITISH HISTORY TUDORS & STUARTS AD 1485 - 1714 The Tudor and Stuart periods saw monumental change in the relationship between Europe and their continental neighbours. As the period begins, we see evidence of integrated societies at different levels of local and national life. By the close, Britain is embarked on a frenzied mission to extend their colonial reach and primed to step into an industrial revolution, powered by the outrageous wealth accumulation made possible by the triangular slave trade. THE COURT OF JAMES IV AD 1488 - 1513 King James IV Scotland had numerous qualities and successes; he united the highlands and lowlands; he created a Scottish navy; and maintained alliances with France and England. It is clear that he was also something of a forerunner in regards multi-culturalism. Records show that many black people were present at the court of James IV – servants yes but also invited guests and musicians. Much of what we know comes from the royal treasurers accounts which show that James’ purse paid wages and gifts to numerous ‘moors’. African drummers and choreographers were paid to perform, to have instruments repainted, or bought horses to accompany James on tour. The records also show black women present being gifted clothing, fabric and large sums of money. CATALINA & CATALINA AD 1501 In 1501 ‘la infant’ Catalina, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, arrived in Plymouth to begin a new life in England. She came from one royal household and was travelling in preparation to be married into another, the fledgling Tudor dynasty. She was promised to Arthur, heir to the English throne. -

The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service

Quidditas Volume 9 Article 9 1988 The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service F. Jeffrey Platt Northern Arizona University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Platt, F. Jeffrey (1988) "The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service," Quidditas: Vol. 9 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol9/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JRMMRA 9 (1988) The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service by F. Jeffrey Platt Northern Arizona University The critical early years of Elizabeth's reign witnessed a watershed in European history. The 1559 Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis, which ended the long Hapsburg-Valois conflict, resulted in a sudden shift in the focus of international politics from Italy to the uncomfortable proximity of the Low Countries. The arrival there, 30 miles from England's coast, in 1567, of thousands of seasoned Spanish troops presented a military and commer cial threat the English queen could not ignore. Moreover, French control of Calais and their growing interest in supplanting the Spanish presence in the Netherlands represented an even greater menace to England's security. Combined with these ominous developments, the Queen's excommunica tion in May 1570 further strengthened the growing anti-English and anti Protestant sentiment of Counter-Reformation Europe. These circumstances, plus the significantly greater resources of France and Spain, defined England, at best, as a middleweight in a world dominated by two heavyweights. -

UCLA Historical Journal

The Early Elizabethan Polity. Stephen Alford. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. xii + 271 pp. Though there has been a recent surge of interest from Hollywood regarding the life, times and events of the reign of England's first Elizabeth, from the excellent whimsical romance of "Shakespeare in Love" to the abominable and inaccurate "Elizabeth I", scholarly attentions paid to Elizabeth and her reign have been scant in most recent years. Indeed, the early years of the Elizabethan era have seen perhaps the least new scholarly activity as the new millennium approaches: the standard work on the formative years of the reign remains Wallace MacCaffrey's The Shaping of the Elizabethan Regime, published in 1967, and the standard biography of her Chief Minister, William Cecil, remains Conyers Read's 1955 work, Mr. Secretary Cecil and Queen Elizabeth, a work which also reinforced the traditional views of a Council rent by faction and Elizabeth as 'Gloriana', playing the factions off one another like a master violinist or puppeteer to gain "harmonious cooperation" within her realm, first proposed in this century by J.E. Neale's 1934 work. Queen Elizabeth.^ Even the standard revisionist views of Elizabeth and of her role in governance, Neville Williams' Elizabeth the First: Queen ofEngland, and Christopher Haigh's Elizabeth I, were published in 1968 and 1988, respectively.'^ Stephen Alford's work. The Early Elizabethan Polity is an important addition to the bodies of work concerned with the early years of Elizabeth's reign and regarding its main subject, William Cecil. Alford presents a prosopographic and institutional study of Cecil, with a focus on his actions and relations at court and in council, particularly as regards the formation of Scottish ' Wallace MacCafTrey, The Shaping ofthe Elizabethan Regime, (Princeton: Princeton Univ. -

Robert Dudley, 1St Earl of Leicester

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, KG (24 June mours that he had arranged for his wife’s death continued 1532 or 1533[note 1] – 4 September 1588) was an English throughout his life, despite the coroner’s jury's verdict of nobleman and the favourite and close friend of Elizabeth accident. For 18 years he did not remarry for Queen Eliz- I from her first year on the throne until his death. The abeth’s sake and when he finally did, his new wife, Lettice Queen giving him reason to hope, he was a suitor for her Knollys, was permanently banished from court. This and hand for many years. the death of his only legitimate son and heir were heavy blows.[2] Shortly after the child’s death in 1584, a viru- Dudley’s youth was overshadowed by the downfall of his family in 1553 after his father, the Duke of Northumber- lent libel known as Leicester’s Commonwealth was circu- land, had unsuccessfully tried to establish Lady Jane Grey lating in England. It laid the foundation of a literary and historiographical tradition that often depicted the Earl as on the English throne. Robert Dudley was condemned to [3] death but was released in 1554 and took part in the Battle the Machiavellian “master courtier” and as a deplorable of St. Quentin under Philip II of Spain, which led to his figure around Elizabeth I. More recent research has led full rehabilitation. On Elizabeth I’s accession in Novem- to a reassessment of his place in Elizabethan government ber 1558, Dudley was appointed Master of the Horse. -

Challenging the Whiteness of Britishness: Co-Creating British Social History in the Blogosphere

Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Special Issue – September 2015 Challenging the Whiteness of Britishness: Co-Creating British Social History in the Blogosphere Deborah Gabriel, Bournemouth University, UK Abstract Blogs are a valuable medium for preserving cultural memory, reflecting the various dimensions of human life (O’Sullivan, 2005) and allowing ordinary individuals and marginalised groups the opportunity to contribute to the ‘dialogue of history’ (Cohen, 2005:10). The diverse perspectives to be found in the blogosphere can help deepen understanding of historical moments. Such examples include 9/11 (Cohen, 2005), the London bombings in 2005 (Allan, 2006) and Hurricane Katrina (Brock, 2009). Using critical race theory (CRT) as a theoretical framework and cultural democracy as the conceptual framework, this study examines the symbolic power of counter-storytelling through the blogosphere. The findings reveal that in relation to coverage of the UK ‘riots’ in 2011 and the Stephen Lawrence verdict in 2012, African Caribbean bloggers advanced alternative perspectives of the events and appropriated blogs as a medium for self-representation through their own constructions of Black identity. In so doing they performed a vital role as co- creators of British social history. 1 Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Special Issue – September 2015 Introduction Historical archives in Britain often exclude or fail to capture the presence and experiences of people of colour (which dates back to the 17th century with the first arrival of slaves from the west coast of Africa), resulting in a ‘whitenening of Britishness’ Bressey (2006:51). The term is defined as a process through which the exclusion of a person’s skin colour in historical records results in the assumption of a white identity (Bressey, 2006). -

Directions for Britain Outside the Eu Ralph Buckle • Tim Hewish • John C

BREXIT DIRECTIONS FOR BRITAIN OUTSIDE THE EU RALPH BUCKLE • TIM HEWISH • JOHN C. HULSMAN IAIN MANSFIELD • ROBERT OULDS BREXIT: Directions for Britain Outside the EU BREXIT: DIRECTIONS FOR BRITAIN OUTSIDE THE EU RALPH BUCKLE TIM HEWISH JOHN C. HULSMAN IAIN MANSFIELD ROBERT OULDS First published in Great Britain in 2015 by The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Westminster London SW1P 3LB in association with London Publishing Partnership Ltd www.londonpublishingpartnership.co.uk The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society by analysing and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2015 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-255-36682-3 (interactive PDF) Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or to reprint should be sought from the Director General at the address above. Typeset in Kepler by T&T Productions Ltd www.tandtproductions.com