Mise En Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M Ard I 6 Jan Vier

Roch-Olivier Maistre, Président du Conseil d’administration Laurent Bayle, Directeur général Mardi 6 janvier Orpheus Dans le cadre du cycle Le modèle Lully Samedi 20 décembre 2008 et mardi 6 janvier 2009 Mardi 6 janvier | Vous avez la possibilité de consulter les notes de programme en ligne, 2 jours avant chaque concert, Orpheus à l’adresse suivante : www.citedelamusique.fr ORPHEUS 06-01.indd 1 31/12/08 13:05 MARDI 6 JANVIER – 20H Salle des concerts Georg Philipp Telemann Orpheus Opéra en trois actes sur un livret anonyme basé sur Orphée de Michel du Boullay – Version de concert Acte I entracte Acte II pause Acte III Opera Fuoco, chœur, orchestre et troupe-atelier David Stern, direction musicale Jay Bernfeld, viole de gambe et co-direction artistique Dietrich Henschel, baryton (Orpheus) Daphné Touchais, soprano (Eurydice) Ann Hallenberg, mezzo-soprano (Orasia) Rainer Trost, ténor (Eurimedes) Marc Labonnette, baryton (Pluto) Camille Poul, soprano (Ismène) Clémentine Margaine, mezzo-soprano (Ascalax) Caroline Meng, soprano (Cephisa) Luanda Siqueira, soprano (La Prêtresse) Matthieu Chapuis, ténor (Un Esprit) Aurélia Marchais, Dorothée Leclair, sopranos (Suivantes d’Orasia) Benoît Pocherot, ténor, Thomas van Essen, basse (Suivants de Pluton) Édition de la partition : Peter Huth. Ce concert est surtitré. Fin du concert vers 23h10. 3 ORPHEUS 06-01.indd 3 31/12/08 13:05 Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) Orpheus On ignore combien Telemann a pu composer d’opéras – lui-même, sans doute, l’avait oublié ! Car l’opéra fut la grande affaire de sa vie, jusqu’en 1735, que ce soit pour Leipzig, dès sa jeunesse, puis pour Bayreuth et surtout à Hambourg. -

Cpo 555 057–2 Booklet.Indd 1 15.01.2020 10:45:20 Florian Leopold Gassmann

Florian Gassmann Ah, ingrato amor Opera Arias Ania Vegry NDR RADIOPHILHARMONIE David Stern cpo 555 057–2 Booklet.indd 1 15.01.2020 10:45:20 Florian Leopold Gassmann cpo 555 057–2 Booklet.indd 2 15.01.2020 10:45:21 Florian Leopold Gassmann (1729–1774) Opera Arias 1 Involarmi, from: Achille in Sciro (Pietro Metastasio) 4'40 2 Se in campo armato, from: Catone in Utica (Pietro Metastasio) 3'26 3 Dovea svenarti allora, from: Catone in Utica (Pietro Metastasio) 2'58 4 Per darvi alcun pegno, from: Catone in Utica (Pietro Metastasio) 5'30 5 Ah, ingrato, amor, from: Achille in Sciro (Pietro Metastasio) 7'39 6 Nessuno consola un povero core, from: L’egiziana bzw. La Zingara 3'39 (Franceso Ronzi) 7 Ah, che son fuor di me, from: L’amore artigiano (Carlo Goldoni) 2'14 8 Che vuoi dir con questi palpiti, from: L’amore artigiano (Carlo Goldoni) 4'53 9 Come mi sprezza ancora (unknown) 2'50 10 Cogli amanti, from: Le serve rivali (Pietro Chiari) 3'33 11 Barbara e non rammenti, from: L’opera seria (Ranieri de‘ Calzabigi) 5'29 12 Delfin che al laccio infido, from: L’opera seria (Ranieri de‘ Calzabigi 4'01 cpo 555 057–2 Booklet.indd 3 15.01.2020 10:45:21 13 Dove son, from: L’opera seria (Ranieri de‘ Calzabigi) 4'36 14 Pallid´ombra, from: L’opera seria (Ranieri de‘ Calzabigi) 6'01 15 Saprei costante e ardita, from: L’opera seria (Ranieri de‘ Calzabigi) 3'20 T.T.: 64'59 Ania Vegry, Soprano NDR RADIOPHILHARMONIE David Stern cpo 555 057–2 Booklet.indd 4 15.01.2020 10:45:21 Ania Vegry (© Simon Pauly) cpo 555 057–2 Booklet.indd 5 15.01.2020 10:45:21 Florian Leopold -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XIX, Number 1 April 2004 THE THOMAS BAKER COLLECTION In 1985 the Music Library of The University of Western Ontario acquired the bulk of the music collection of Thomas Baker (c.1708-1775) of Farnham, Surrey from the English antiquarian dealer Richard Macnutt with Burnett & Simeone. Earlier that same year what is presumed to have been the complete collection, then on deposit at the Hampshire Record Office in Winchester, was described by Richard Andrewes of Cambridge University Library in a "Catalogue of music in the Thomas Baker Collection." It contained 85 eighteenth-century printed titles (some bound together) and 10 "miscellaneous manuscripts." Macnutt described the portion of the collection he acquired in his catalogue The Music Collection of an Eighteenth Century Gentleman (Tunbridge Wells, 1985). Other buyers, including the British Library, acquired 11 of the printed titles and 4 of the manuscripts. Thomas Baker was a country gentleman and his library, which was "representative of the educated musical amateur’s tastes, include[d] works ranging from short keyboard pieces to opera" (Macnutt, i). Whether he was related to the Rev. Thomas Baker (1685-1745) who was for many years a member of the choirs of the Chapel Royal, St. Paul’s Cathedral, and Westminster Abbey, is not clear. Christoph Dumaux as Tamerlano – Spoleto Festival USA 2003 However, his collection did contain several manuscripts of Anglican Church music. TAMERLANO AT SPOLETO The portion of the Thomas Baker Collection now at The University of Western Ontario, consisting of 83 titles, is FESTIVAL USA 2003 admirably described on the Music Library’s website Composer Gian Carlo Menotti founded the Festival dei (http://www.lib.uwo.ca/music/baker.html) by Lisa Rae Due Mondi in 1958, locating it in the Umbrian hilltown of Philpott, Music Reference Librarian. -

L'elisir D'amore, Malatesta Dans Don Pasquale, Le Père Dans Hansel Et Gretel, Frank Dans Die Fledermaus Ou Encore Enée Dans Didon Et Enée

L’Elisir d’Amore Musique Gaetano Donizetti Livret Felice Romani d’après Le Philtre d’Eugène Scribe Avec Vannina Santoni, Adina, Sahy Ratianarinaivo, Nemorino, Oded Reich, Belcore, Hyalmar Mittroti, Dulcamara, Eleonora de la Pena, Giannetta Orchestre Opera Fuoco Direction David Stern Avec l’Ensemble Vocal de Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, sous la direction de Valérie Josse Claude Massoz, professeur de technique vocale de l’EVSQY Création En Famille dès 11 ans Dossier de presse Scènes ouvertes Les 16 et 17 janvier 2014 __ Spectacle à 20h30 Prix des places : 11 à 21 € Réservation au 01 30 96 99 00 Photo : © D.R. Contact presse Véronique Cartier - Tél : 01 30 96 99 36 - Fax : 01 30 96 99 29 Mail : [email protected] L’Elisir d’Amore Gaetano Donizetti / David Stern Le Théâtre de Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines présente L’Elisir d’Amore, musique Gaetano Donizetti, livret Felice Romani d’après Le Philtre d’Eugène Scribe, les 16 et 17 janvier prochains. Sous la direction de David Stern, Opera Fuoco se saisit avec brio et légèreté de ce petit bijou du répertoire lyrique. Un mélodrame joyeux, tout en finesse et en ironie, sur l’amour et ses mystères, entre bel canto et envolées romantiques. Délicieux ! La scène se passe dans un village basque à la fin du XVIIIe siècle. Amoureux transi de la riche et capricieuse fermière Adina, le jeune Nemorino, sans le sou et timide, ne fait pas le poids face au fringant sergent Belcore. Celui-ci a sorti la grosse artillerie pour emporter le beau coeur d’Adina : bouquet de fleurs en-veux- tu-en-voilà, déclaration enflammée et demande en mariage express ! Le soupirant éconduit tente alors de forcer le destin en achetant à un charlatan ambulant un philtre d’amour (produit dans les vignobles bordelais !).. -

Edition 1 | 2019-2020

insidewhat’s 2019-2020 SEASON Letter from Chairman 9 Palm Beach Opera Orchestra 42 Board of Directors 10 Artist Training Programs 43 General Director’s Welcome 11 Alumni Highlights 44 Co-Producer Society & Benenson Young Artists 48 Program Sponsors 12 Bailey Apprentice Artists 49 Hansel and Gretel 26 Palm Beach Opera Studio 51 Cast of Characters 27 Education & Community Director’s Notes 28 Engagement Programs 52 Synopsis 29 PBO Young Friends 53 The History of Hansel and Gretel 31 Community Events & Production Team 32 Adult Engagement 54 Artists 35 Palm Beach Opera Guild 55 Creative Team 38 Supporters 56 Production Staff 40 Palm Beach Opera Staff 64 Children’s Chorus 41 Orpheus Legacy Society 65 ADVERTISING This program is published in association with Onstage Publications Onstage Publications, 1612 Prosser Avenue, Kettering, OH 45409. This program may not be 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 reproduced in whole or in part without written e-mail: [email protected] permission from the publisher. JBI Publishing is a www.onstagepublications.com division of Onstage Publications, Inc. Contents © 2019. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. PALM BEACH OPERA 7 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN DEAR PALM BEACH OPERA PATRONS, Welcome to the first production of the 19-20 season! We are grateful that you decided to spend the evening with us and we look forward to sharing the season with you. Thanks to your continued patronage and support, last season Palm Beach Opera achieved an operating surplus for the third year in a row. At the same time, we expanded our young artist and community outreach programs to have a greater impact in our community. -

Cosi Fan Tutte Ok

Cosi fan Tutte Cosi fan Tutte (K.588) ou L’école des amants Musique Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Livret Lorenzo da Ponte Avec Chantal Santon (Fiordiligi - soprano), Caroline Meng (Dorabella - soprano ), Natalie Perez (Despina - soprano ), Pierrick Boisseau (Don Alfonso - baryton ), - Cyrille Dubois (Ferrando- ténor), Jean-Gabriel Saint-Martin (Guglielmo- baryton) Opera Fuoco / Direction David Stern David Stern et sa compagnie Opera Fuoco sont en résidence au Théâtre de Saint-Quentin-en- Yvelines Dossier de presse e Scènes ouvertes Les 29 et 30 mars 2013 __ Vendredi 29 et samedi 30 mars à 20h30 Prix des places : 6 à 21 € Réservation au 01 30 96 99 00 Photo : © D.R. Contact presse Véronique Cartier - Tél : 01 30 96 99 36 - Fax : 01 30 96 99 29 Mail : [email protected] Cosi fan Tutte Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart / Opera Fuoco / David Stern Le Théâtre de Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines présente Cosi fan Tutte, musique de Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, livret Lorenzo da Ponte, avec Opera Fuoco, direction David Stern, les 29 et 30 mars prochains. David Stern et les interprètes d’Opera Fuoco s’emparent du chef-d’œuvre de Mozart, avec le talent et l’énergie qui les caractérisent. Un pur moment de bonheur, entre gravité et légèreté, sur un thème universel : l’amour et ses mésaventures ! Cosi fan Tutte ou L’école des amants est une expérience amoureuse diabolique. Sous la baguette d'un philosophe désabusé, Don Alfonso, deux jeunes officiers acceptent un pari apparemment stupide : séduire la promise de l'autre pour éprouver ses sentiments et tester sa fidélité… Dans cet opéra de la double inconstance - l'infidélité des deux soeurs, Fiordiligi et Dorabella, comme le jeu trouble de leurs fiancés, Guglielmo et Ferrando – tout s'entremêle et s'embrouille : le cynisme des manipulateurs et la naïveté des manipulés, les bons sentiments et les désirs secrets, la mascarade des déguisements et la gravité des révélations amoureuses. -

Giovanni Legrenzi La Divisione Del Mondo

Giovanni Legrenzi La divisione del mondo Freitag 30. August 2019 19:00 Kölner Philharmonie Felix_Cover_Vordruck.indd 2 15.07.19 09:51 Felix_Cover_Vordruck.indd 3-4 15.07.19 09:51 Baroque ... Classique 1 Carlo Allemano TENOR (GIOVE) Stuart Jackson TENOR (NETTUNO) André Morsch BARITON (PLUTONE) Arnaud Richard BARITON (SATURNO) Axelle Fanyo SOPRAN (JUNO) Sophie Junker SOPRAN (VENERE) Jake Arditti COUNTERTENOR (APOLLO) Paul-Antoine Bénos-Djian COUNTERTENOR (MARTE) Soraya Mafi SOPRAN (DIANA) Ada Elodie Tuca SOPRAN (AMore | CuPIDO) Rupert Enticknap COUNTERTENOR (MERCURIO) Alberto Miguélez Rouco COUNTERTENOR (DISCORDIA) Les Talens Lyriques Christophe Rousset DIRIGENT Freitag 30. August 2019 19:00 Pause gegen 20:40 Ende gegen 22:00 Gefördert durch das Kuratorium KölnMusik e. V. Felix_Cover_Vordruck.indd 3-4 15.07.19 09:51 Eva Kleinitz war ein Begriff in der Welt der Oper Am 30. Mai 2019 verstarb Eva Kleinitz. Sie war viele Jahre eine treibende Kraft bei den Bregenzer Festspielen. Nach Stationen als Betriebsdirektorin der Oper La Monnaie in Brüssel und Direktorin der Stuttgarter Staatsoper wurde sie 2017 Intendantin der Opéra national du Rhin in Straßburg, wo sie eine fulminante Programmierung durchsetzen konnte. Ihr herausragendes Gespür, begabte Sängerinnen und Sänger zu entdecken und diese dann zu fördern, ermöglichte es ihr, großartige Rollendebüts zu initiieren. Eine Fähigkeit, für die sie weithin geschätzt wurde. Überhaupt standen die Künst lerinnen und Künstler immer im Mittelpunkt ihrer Arbeit als Intendantin. Eva Kleinitz hatte eine geradezu enzyklopädische Repertoire kenntnis und sie scheute sich nicht, völlig unbekannte, seit Jahrhunderten nicht aufgeführte Werke wieder auf die Bühne zu bringen, und das mit großem Erfolg. 2 Giovanni Legrenzis La divisione del mondo war eines der Werke, die sie an der Operá national du Rhin in Straßburg programmiert hat, wo sie Christophe Rousset als musika lischen Partner an ihrer Seite wusste. -

La Finta Giardiniera

Pasquale Anfossi Samedi 1er avril - 19h30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Dimanche 2 avril - 16h00 Durée de chaque ouvrage : 3h avec un entracte Pourquoi ce projet ? A l‘occasion du 250e anniversaire de la naissance de Mozart (1756-1791), la Fondation Royaumont souhaite proposer un projet original qui permet une écoute renouvelée de l'oeuvre de Mozart, en fonc- tion des interrogations actuelles des artistes et musicologues sur l'interprétation de son oeuvre. En par- ticulier l'idée est de replacer Mozart parmi ses contemporains : les voyages de Mozart en Italie et son amour de l'opéra sont connus, à une époque où l'opéra italien, en particulier l'opéra bouffe napolitain, était le grand modèle dominant dans toute l'Europe. Quelle est l'influence de ce style sur l'écriture de Mozart ? La découverte d'une partition napolitaine directement à l'origine d'une commande à Mozart, celle de Pasquale Anfossi à la Bibliothèque Nationale de France, a permis d'imaginer concrètement cette confrontation, en présentant deux versions de La Finta Giardiniera. Le choix de chefs avec leurs orchestres sur instruments d'époque est déterminant aussi par le renouvel- lement que chacun d'eux apporte à l'interprétation des oeuvres de cette époque charnière entre baroque et classique au XVIIIème siècle : respectivement les napolitains Antonio Florio et sa Cappella de'Tur- chini pour l'opéra napolitain, style qu'ils défendent depuis de nombreuses années, et David Stern, grand mozartien qui a créé son orchestre consacré à l'opéra sur instruments d'époque, Opera Fuoco, en 2003. Les deux oeuvres sont confiées au même metteur en scène, Stephan Grögler, qui aime puiser son ins- piration dans la musique, ce qui permettra de mieux souligner les ressemblances et les originalités profondes de chaque oeuvre. -

Discograhy-Oratorios Dramas Serenades Odes

George Frideric Handel Oratorios, Dramas, Serenades and Odes Discography The following spreadsheet, prepared by Philippe Gelinaud, isn't an exhaustive discography of Handel's oratorios, dramas, serenades and odes, but represents a compilation assembled from LP, CD and DVD collections and various catalogs. If you are aware of any additional (commercial) Handel oratorio, drama, serenade or ode, recordings not listed here, please provide Mr. Gelinaud ([email protected]) with this information. Aci, Galatea e Polifemo - HWV 72 Joshua - HWV 64 HWV 46a - Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno HWV 56 - Messiah Acis and Galatea - HWV 49 Judas Maccabaeus - HWV 63 HWV 47 - La Resurrezione HWV 57 - Samson Alexander Balus - HWV 65 Messiah - HWV 56 HWV 72 - Aci, Galatea e Polifemo HWV 58 - Semele Alexander's Feast - HWV 75 Occasional Oratorio - HWV 62 HWV 74 - Eternal Source of Light Divine HWV 59 - Joseph and his brethren L'Allegro, il Moderato ed il Penseroso - HWV 55 Il Parnasso in Festa - HWV 73 HWV 48 - Brockes Passion HWV 60 - Hercules Athalia - HWV 52 La Resurrezione - HWV 47 HWV 49 - Acis and Galatea HWV 61 - Belshazzar Belshazzar - HWV 61 Samson - HWV 57 HWV 50a - Esther HWV 62 - Occasional Oratorio Brockes Passion - HWV 48 Saul - HWV 53 HWV 50b - Esther HWV 63 - Judas Maccabaeus The Choice of Hercules - HWV 69 Semele - HWV 58 HWV 51 - Deborah HWV 64 - Joshua Deborah - HWV 51 Solomon - HWV 67 HWV 52 - Athalia HWV 65 - Alexander Balus Esther - HWV 50a Song for St Cecilia's Day - HWV 76 HWV 73 - Parnasso in Festa HWV 66 - Susanna Esther -

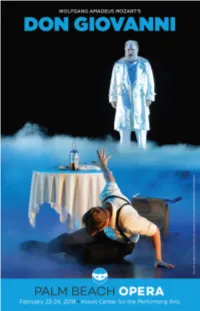

Edition 3 | 2018-2019

insidewhat’s 2018-2019 SEASON Letter from Chairman 9 Artists 35 Board of Directors 10 Creative Team 41 General Director’s Welcome 11 Production Staff 43 Co-Producer Society & Palm Beach Opera Chorus 44 Program Sponsors 12 Palm Beach Opera Orchestra 46 Don Giovanni 29 Benenson Young Artists 48 Cast of Characters 30 Apprentice Artists 49 Director’s Notes 31 Orpheus Legacy Society 56 Synopsis 32 Supporters 58 Production Team 33 Palm Beach Opera Staff 64 ADVERTISING Onstage Publications 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 e-mail: [email protected] www.onstagepublications.com This program is published in association with Onstage Publications, 1612 Prosser Avenue, Kettering, OH 45409. This program may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher. JBI Publishing is a division of Onstage Publications, Inc. Contents © 2019. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. PALM BEACH OPERA 5 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN DEAR OPERA FRIENDS, Welcome to our mid-season production of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Don Giovanni! Hopefully, many of you were able to attend one of our La traviata performances. The singers, the chorus and orchestra, and in particular also the large scale production received wonderful audience acclaim and generated a lot of excitement. Thanks to all of your support, we are able to present large scale productions. I’d like to thank, in particular, all the Co-Producer Society members for their ongoing generosity. We endeavor to bring you an engaging variety of productions. This weekend’s production of Don Giovanni takes a much different dramatic approach. -

Cosi Fan Tutte Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Opera Fuoco / David Stern

2012 THÉÂTRE 2013 DE ST-QUENTIN- EN-YVELINES Scène nationale COSI FAN TUTTE WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART OPERA FUOCO / DAVID STERN opéra Version concert vendredi 29 mars 20h30 samedi 30 mars 20h30 grand théâtre - durée 3h avec entracte David Stern et Opera Fuoco, dans le cadre de leur résidence à la Scène na- tionale, s’emparent avec talent du chef- d’œuvre le plus radieux écrit par Mozart, Cosi fan tutte. Farce invraisemblable, fable philoso- phique sur l’amour, tragi-comédie ro- mantique et désespérée, Cosi fan tutte est tout cela… et plus. Mozart et son librettiste Lorenzo Da Ponte imagi- nent un sujet original sur la fidélité des femmes. Ils sont six chanteurs-comédiens-musi- ciens sur scène pour jouer cette médi- tation douce-amère sur fond de travestissements, de faux adieux et de tromperies – Cosi fan tutte signifiant « Ainsi font-elles toutes », autrement dit « Toutes les femmes trompent les © D.R. hommes ». Un pur moment de bonheur, entre gra- vité et légèreté, sur un thème univer- 01 30 96 99 00 sel : l’amour et ses mésaventures ! www.theatresqy.org © D.R L’intrigue se déroule au XVIIIe siècle dans la - En juin 2013, Concert Mozart associant baie de Naples. Ferrando et Guglielmo pa- 250 enfants de primaire et collège à l’or- rient avec Don Alfonso sur la fidélité de leurs chestre d’Opera Fuoco. amantes, Fiordiligi et Dorabella. Après avoir - En mai 2014, création d’une production simulé un départ pour la guerre, Ferrando et mettant en scène un Opéra, Cosi Fanciulli, Guglielmo reviennent déguisés et tentent commande passée par Opera Fuoco à Nico- chacun de séduire la belle de l’autre. -

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Monteverdi Choir & English Baroque Soloists

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Monteverdi Choir & English Baroque Soloists Màrius Sampere, “Subllum”, Subllum (2000) “[...] El món és cruel i només hi ha un llum, el que il·lumina la crueltat del món i també la meva, més oculta. Alba, mira’m!, veuràs que duc escrites a la cara les paraules dels morts. Aquell Qui n’encapçala la taula no em permet de somriure. No hi ha prou claror.” Programa Palau 100 Escena III Dimecres, 24.04.2019 – 20 h Recitatiu. Ah, wretched prince (Cadmus, Athamas) Sala de Concerts 14. Acompanyat. Wing’d with our fears and pious haste (Cadmus) Escena IV Louise Alder, Semele 15. Cor. Hail Cadmus, hail! Hugo Hymas, Júpiter 17. Cor. Endless pleasure, endless love Lucile Richardot, Ino/Juno Carlo Vistoli, Athamas Gianluca Burratto, Cadmus/Somnus ACTE II Monteverdi Choir 18. Simfonia English Baroque Soloists Sir John Eliot Gardiner, director Escena I Thomas Guthrie, codirector Recitatiu. Iris, impatient of thy stay (Juno, Iris) 19. There, from mortal cares retiring (Iris) Rick Fisher, dissenyador de llums Recitatiu. No more! I’ll hear no more! (Juno) Patricia Hofstede, vestuari 20. Awake, Saturnia, from thy lethargy! (Juno, Iris) 21. Hence, hence, Iris, hence away (Juno) Georg Friedrich Händel (1685-1759) Escena II Semele, HWV 58 (versió de concert) Ària. Come, Zephyrs, come (Cupid) 22. Oh sleep, why dost thou leave me? (Semele) Overtura Escena III Recitatiu. Let me not another moment (Semele) Gavotte 23. Lay your doubts and fears aside (Jupiter) Recitatiu. You are mortal (Jupiter) 24. With fond desiring (Semele) ACTE I 25. Cor. How engaging, how endearing Recitatiu.