Locating the Wallachian Revolution of *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Influence Matrix Romania

N O V E M B E R 2 0 1 9 MEDIA INFLUENCE MATRIX: ROMANIA Author: Dumitrita Holdis Editor: Marius Dragomir Published by CEU Center for Media, Data and Society (CMDS), Budapest, 2019 About CMDS About the authors The Center for Media, Data and Society Dumitrita Holdis works as a researcher for the (CMDS) is a research center for the study of Center for Media, Data and Society at CEU. media, communication, and information Previously she has been co-managing the “Sound policy and its impact on society and Relations” project, while teaching courses and practice. Founded in 2004 as the Center for conducting research on academic podcasting. Media and Communication Studies, CMDS She has done research also on media is part of Central European University’s representation, migration, and labour School of Public Policy and serves as a focal integration. She holds a BA in Sociology from point for an international network of the Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca and a acclaimed scholars, research institutions and activists. MA degree in Sociology and Social Anthropology from the Central European University. She also has professional background in project management and administration. She CMDS ADVISORY BOARD has worked and lived in Romania, Hungary, France and Turkey. Clara-Luz Álvarez Floriana Fossato Ellen Hume Monroe Price Marius Dragomir is the Director of the Center Anya Schiffrin for Media, Data and Society. He previously Stefaan G. Verhulst worked for the Open Society Foundations (OSF) for over a decade. Since 2007, he has managed the research and policy portfolio of the Program on Independent Journalism (PIJ), formerly the Network Media Program (NMP), in London. -

Viața La Sat În Perioada Comunistă

Flavius-Cristian MĂRCĂU Sorin PUREC VIAȚA LA SAT ÎN PERIOADA COMUNISTĂ COORDONATORI: Flavius-Cristian MĂRCĂU Sorin PUREC VIAȚA LA SAT ÎN PERIOADA COMUNISTĂ Editura Academica Brâncuși Editor: Flavius-Cristian MĂRCĂU Corectură: Iuliu-Marius MORARIU ISBN 978-973-144-783-4 EDITURA ACADEMICA BRÂNCUȘI ADRESA: Bd-ul Republicii, nr. 1 Târgu Jiu, Gorj Tel: 0253/218222 COPYRIGHT: Sunt autorizate orice reproduceri fără perceperea taxelor aferente cu condiţia precizării sursei. Responsabilitatea asupra conţinutului lucrării revine în totalitate autorilor. CUPRINS I 1 Sorin PUREC Prefață 7 2 Flavius-Cristian Moștenirile comuniste și memoria 13 MĂRCĂU nostalgică din statele Cetral- Europene 3 Iuliu-Marius Elemente ale opresiunii comuniste în 31 MORARIU localitatea Salva, județul Bistrița- Năsăud 4 Bianca OSMAN Manifestări ale mentalului colectiv. 45 rolul mass-media în formarea conștiinței individuale și de grup în perioada 1965-1990 II 5 Bianca OSMAN Interviu cu ADRIAN GORUN 65 6 Bianca OSMAN Interviu cu GEORGE NICULESCU 87 7 Claudia Interviu cu GHEORGHE GORUN 103 ȘOIOGEA 8 Claudia Interviu cu NICOLAE BRÎNZAN 121 ȘOIOGEA 9 Iuliu-Marius Interviu cu GRIGORE FURCEA 137 MORARIU 5 10 Iuliu-Marius Interviu cu DOREL MITITEAN 149 MORARIU 11 Bianca Interviu cu P. C. 161 LĂZĂROIU 12 Bianca OSMAN Interviu cu SIMA AUREL 167 13 Claudia Interviu cu CĂLUGĂRU ANGELA 173 ȘOIOGEA 14 Oana CALOTĂ Interviu cu NICU PÎRVULEȚ 179 15 Iuliu-Marius Interviu cu RADU BOTIȘ 189 MORARIU 16 Maria Interviu cu CIOCOIU OTILIA 195 VÎLCEANU 17 Costina Vergina Interviu cu CONSTANTIN 201 ȘTEFĂNESCU STEFĂNESCU 6 PREFAȚĂ „Cei care uita trecutul sunt condamnați sa îl repete”. George Santayana Ca să nu uităm dramele care ne-au marcat pe noi sau pe părinții și pe bunicii noștri, cartea de față adună, prin eforturile studenților noștri, o serie de interviuri realizate cu oameni care au petrecut ani ai regimului comunist la țară. -

The Behavioural Dynamics of Romania's Foreign Policy In

THE BEHAVIOURAL DYNAMICS OF ROMANIA’S FOREIGN POLICY IN THE LATE 1990s: THE DRIVE FOR SECURITY AND THE POLITICS OF VOLUNTARY SERVITUDE Eduard Rudolf ROTH Abstract. This article investigates the nature, the magnitude and the impact of the exogenously articulated preferences in the articulation of Romania’s foreign policy agenda and behavioural dynamics during the period 1996-2000. In this context, the manuscript will explore Romania’s NATO and (to a lesser extent) EU accession bids, within an analytical framework defined by an overlapped interplay of heterochthonous influences, while trying to set out for further understanding how domestic preferences can act as a transmission belt and impact on foreign policy change in small and medium states. Keywords: Romanian foreign policy, NATO enlargement, EU enlargement, Russian-Romanian relations, Romanian-NATO relations, Romania-EU relations 1. Introduction By 1995 – with the last stages of the first Yugoslav crisis confirming that Moscow cannot adequately get involved into complex security equations – and fearing the possible creation of a grey area between Russia and Western Europe, Romanian authorities embarked the country on a genuinely pro-Western path, putting a de facto end to the dual foreign policy focus, “ambivalent policy”,1 “double speak”2 or “politics of ambiguity” 3 which dominated Bucharest’s’ diplomatic exercise throughout the early 1990s. This spectral shift (which arguably occurred shortly after Romanian President Iliescu’s visit in Washington) wasn’t however the result of a newly-found democratic vocation of the indigenous government, but rather an expression of the conviction that such behaviour could help the indigenous administration in its attempts to secure the macro-stabilization of the country’s unreformed economy and to acquire security guarantees in order to mitigate the effects of the political and geographical pressures generated by the Transdniestrian and Yugoslav conflicts, or by the allegedly irredentist undertones of Budapest’s foreign policy praxis. -

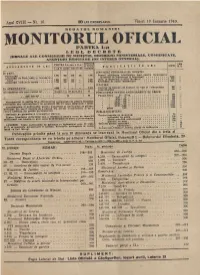

Monitorul Oficial Din a Treiazi Toatà Corespondenta Se Va Trimite Pe Adresa :Monitorul Oficial, Bucureti I.Bulevardul Elisabeta, 29 Telegramemon1toficial

Anul CVIII Nr. 16. lo LEI EXEMPLARCIL Vineri 19 Ianuarie 1940. REGATUL ROMANIEI MONITORULPARTEA I-a OFICIAL LEGI, DECRETE JURNALE ALE CONSILIULUI DE MINISTRY,DECIZIUNI MINISTERIALE, COMUNICATE, ANUNTURI )IUDICIARE (DE INTERES GENERAL). PARTEA I-a sau a II-a Detbaterile LINIA ABONAMENTE IN LEI rlamont. PUBLIC ATII Itt LEI laterbe M. 0, I an 16 luni 3 luni 1 lunftpsesitine JURNALELE CONSILIULUI DE MINISTRI IN TARA: Pentru acordarea avantajelor legil pentru incurajarea 1900 1 950 475 160 1200 Particu lari 3.000 Autoritftti de Stat, judet si comune ur- industriel la industrlasi si fabricantl... ..... 1.200 Idem, la meseriasi si mori taranesti . 700 bane 1 600 800 400 L000 AutoritAti comunale rurale 1.100 '350 275 1.200 Schimbitri de nume 1neetAteniri . CITATIILE 2.400 Curtilor de Casatie, de Conturi, de Apel siI ribunalelor 300 4 0(Xl 150 IN STRAINATATE Judeciitorillor ... .. 1:1n exemplar din anul curent lei 10 part. I-a15 part. Il-a 10 PUBLICATIILE PENTRU AMENAJAMENTE DE PADURI 100 20 Padurl intre 0 10 ha anti trecull . 30 10,01 20 200 2E,01 100 .. 300 Abonamentul la partea Ill-a (Desbateri e parlamentare) pentru sesiunile 100,01 200 1.000 prelunglte sau extraordinare se socoteste 200 lei lunar (minimum 1luni). 200,01 500 1500 500.01-1000 2.000 Abonamentele si publicatille pentru autoritAti si particulari se plAtesc 3 000 anticipat. Ele vor fi insotite de o adresâ din parten utoritAtilor si de o : peste 1000 cerere timbrati din partea particularllor PUBLICATII DIVERSL Institutia nu garanteaza transportul ziarutui. Pentru brevete de inventium 70 Pentru trimiterea chitantelor sau a ziaruluii pentru cereri de lamuriri schimbAri de nume . -

Managementul Timpului În Eficientizarea Activității Instituției De Învățământ

UNIVERSITATEA PEDAGOGICĂ DE STAT „ION CREANGĂ” Cu titlu de manuscris CZU: 37.01(043.3) MELNIC NATALIA MANAGEMENTUL TIMPULUI ÎN EFICIENTIZAREA ACTIVITĂȚII INSTITUȚIEI DE ÎNVĂȚĂMÂNT SPECIALITATEA 531.01 – TEORIA GENERALĂ A EDUCAȚIEI Teză de doctor în științe pedagogice Conducător științific: Cojocaru Vasile, doctor habilitat în pedagogie, profesor universitar Autorul: Melnic Natalia Chișinău, 2019 © MELNIC NATALIA, 2019 2 CUPRINS ADNOTARE (română, rusă, engleză) ………………………………………………… 5 INTRODUCERE ……………………………………………...……………………… 8 1. TIMPUL CA RESURSĂ A EDUCAȚIEI ŞI CONDIŢII DE EFICIENŢĂ ÎN PERSPECTIVA MANAGEMENTULUI INSTITUŢIEI DE ÎNVĂŢĂMÂNT …. 19 1.1. Conceptul și fațetele timpului din perspectiva filosofică, socială, pedagogică …... 19 1.2. Formele de existenţă şi caracteristicile timpului ...................................................... 24 1.3. Timpul ca resursă a educaţiei şi condiţii de eficienţă ............................................... 35 1.4. Managementul instituţiei de învăţământ în context temporal şi de schimbare ......... 41 1.5. Concluzii la capitolul 1 …………………………………………………………..... 52 2. MANAGEMENTUL TIMPULUI ÎN DEZVOLTAREA PERSONALĂ ȘI ORGANIZAȚIONALĂ ………………………………………………………………. 53 2.1. Managementul timpului în perspectiva eficienţei instituţiei de învăţământ ............. 53 2.2. Managementul timpului în implementarea curriculumului educaţional ................... 61 2.3. Proiectarea formării competenţelor în timp .............................................................. 76 2.4. Managementul timpului universitar -

Changing Identities at the Fringes of the Late Ottoman Empire: the Muslims of Dobruca, 1839-1914

Changing Identities at the Fringes of the Late Ottoman Empire: The Muslims of Dobruca, 1839-1914 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Catalina Hunt, Ph.D. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Carter V. Findley, Advisor Jane Hathaway Theodora Dragostinova Scott Levi Copyright by Catalina Hunt 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the Muslim community of Dobruca, an Ottoman territory granted to Romania in 1878, and its transformation from a majority under Ottoman rule into a minority under Romanian administration. It focuses in particular on the collective identity of this community and how it changed from the start of the Ottoman reform era (Tanzimat) in 1839 to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. This dissertation constitutes, in fact, the study of the transition from Ottoman subjecthood to Romanian citizenship as experienced by the Muslim community of Dobruca. It constitutes an assessment of long-term patterns of collective identity formation and development in both imperial and post-imperial settings. The main argument of the dissertation is that during this period three crucial factors altered the sense of collective belonging of Dobrucan Muslims: a) state policies; b) the reaction of the Muslims to these policies; and c) the influence of transnational networks from the wider Turkic world on the Muslim community as a whole. Taken together, all these factors contributed fully to the community’s intellectual development and overall modernization, especially since they brought about new patterns of identification and belonging among Muslims. -

Ethno-Confessional Realities in the Romanian Area: Historical Perspectives (XVIII-XX Centuries)

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Ethno-Confessional Realities in the Romanian Area: Historical Perspectives (XVIII-XX centuries) Brie, Mircea and Şipoş, Sorin and Horga, Ioan University of Oradea, Romania 2011 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/44026/ MPRA Paper No. 44026, posted 30 Jan 2013 09:17 UTC ETHNO-CONFESSIONAL REALITIES IN THE ROMANIAN AREA: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES (XVIII-XX CENTURIES) ETHNO-CONFESSIONAL REALITIES IN THE ROMANIAN AREA: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES (XVIII-XX CENTURIES) Mircea BRIE Sorin ŞIPOŞ Ioan HORGA (Coordinators) Foreword by Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU Oradea 2011 This present volume contains the papers of the international conference Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union’s East Border (workshop: Ethno-Confessional Realities in the Romanian Area: Historical Perspectives), held in Oradea between 2nd-5th of June 2011. This international conference, organized by Institute for Euroregional Studies Oradea-Debrecen, University of Oradea and Department of International Relations and European Studies, with the support of the European Commission and Bihor County Council, was an event run within the project of Action Jean Monnet Programme of the European Commission n. 176197-LLP-1- 2010-1-RO-AJM-MO CONTENTS Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU Foreword ................................................................................................................ 7 CONFESSION AND CONFESSIONAL MINORITIES Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU Confessionalisation and Community Sociability (Transylvania, 18th Century – First Half of the -

Ediția Tipărită

Spitalele COVID-19 din județul Cluj sunt „la limită”! Spitalele clujene abia mai fac față pandemiei, cazurile de COVID-19 fiind într-o creștere continuă. P. 5 monitorul deweekend Anul XXIV, nr. 50 (5962) ¤ 12 – 14 MARTIE 2021 ¤ 12 pagini ¤ 1,50 lei Ediţie de VINERI – SÂMBĂTĂ – DUMINICĂ a cotidianului Nouă țări suspendă Locuitorii din zona Hoia Elevii vor chitanţă vaccinarea cu AstraZeneca cer drumuri decente pe meditaţii Agenţia Italiană a Medicamentului a decis, Proprietarii de case din apropierea Pădurii Elevii cer ca profesorii să fiscalizeze meditaţiile, joi, să oprească imunizarea cu serul produs Hoia vor pietruirea drumurilor: „Nu au iar cei care nu acceptă, să fie sancţionaţi: de Oxford AstraZeneca. Pagina 3 acces pompierii și ambulanțele”. Pagina 2 „Nu mai vrem corupţie”. Pagina 4 Clujenii își iau adio de la cel mai iubit Bunic! A murit Nea Sandu, bunicul din clipurile lui Mircea Bravo Bătrânelul simpatic din clipurile lui Mircea Bravo, știut de români ca Domnu’ Sandu, a murit.„De astăzi, Valea Chintăului din Cluj este mult mai săracă”. Pagina 7 ACTUALITATE SITUAȚIA EPIDEMIOLOGICĂ Vin ninsori și vicol, la Cluj. ÎN JUDEȚUL CLUJ Cod galben în 16 județe. 11 mar e 2021 Administraţia Naţională de Meteorologie a emis o atenţionare VINERI SÂMBĂTĂ DUMINICĂ cod galben de ninsori şi viscol la munte şi precipitaţii mixte, polei şi intensifi cări temporare ale vântului, în restul ţării. METEO 0 0 0 Codul galben intră în vigoare vineri la ora 2:00 şi va expi- cazuri ra la ora 18:00, anunţând ninsori în general moderate canti- 216 7 C 4 C 10 C tativ şi viscol la munte. -

Loving Designs: Gendered Welfare Provision, Activism and Expertise in Interwar Bucharest

LOVING DESIGNS: GENDERED WELFARE PROVISION, ACTIVISM AND EXPERTISE IN INTERWAR BUCHAREST By Alexandra Ghiț Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate in Comparative Gender Studies Supervisor: Professor Susan Carin Zimmermann Budapest, Hungary 2019 CEU eTD Collection Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................................................................i Copyright Notice ......................................................................................................................................................... iii Abstract.........................................................................................................................................................................iv Ackowledgements ........................................................................................................................................................vi List of Figures and Tables ......................................................................................................................................... viii List of Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................................................ix Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. -

Student În Timp De Pandemie

Student în timp de pandemie 50 de povești despre viața în izolare socială Coordonator: Bogdan Nadolu Presa Universitară Clujeană 2020 Referenţi ştiinţifici: Prof. univ. dr. Dan Chiribucă Prof. univ. dr. Alin Gavreliuc ISBN 978-606-37-0789-6 © 2020 Coordonatorul volumului. Toate drepturile rezer‐ vate. Reproducerea integrală sau parţială a textului, prin orice mijloace, fără acordul coordonatorului, este interzisă şi se pedep‐ seşte conform legii. Universitatea Babeş‐Bolyai Presa Universitară Clujeană Director: Codruţa Săcelean Str. Hasdeu nr. 51 400371 Cluj‐Napoca, România Tel./Fax: (+40)‐264‐597.401 E‐mail: [email protected] http://www.editura.ubbcluj.ro/ Cuprins Introducere 5 Și așa a fost trăită pandemia – Delia Nadolu 8 1. Tot cu pandemia, tot cu dorul. Joi, 19 martie 2020, Ionela-Petronela Spătaru 17 2. 2. 26 martie – a 12-a zi de carantină, Ștefania Lazăr 19 3. Dragă jurnalule..., Adina Lupu 20 4. O zi din viața mea, Adina Trușcă 22 5. Jurnal de activități - 29.03.2020, Ana-Maria Fetti 24 6. Jurnal de carantină - 29.03.2020, Renta Trofin 26 7. Jurnalul unui student care trăiește vremurile pandemiei 2020, Lia Moraru 27 8. Jurnal – ziua 8, Flavius Rus 31 9. O zi in (auto)izolare - 31.03.2020, Ștefana Baicu 33 10. Pagini prăfuite, Alexandra Putanu 35 11. Student pe timp de criză - 2 aprilie 2020, Andreea Pantiș 38 12. O zi în izolare – 3 aprilie 2020, Gabriela Iliescu 40 13. Student in Timp de criza – 03 aprilie 2020, Bianca Radic 41 14. Încă o nouă zi de auto-izolare – 3 aprilie 2020, Sorana Diana Blaj 43 15. -

Minorities in the Age of Globalization and Localization: the Vlach

International e-ISSN:2587-1587 SOCIAL SCIENCES STUDIES JOURNAL Open Access Refereed E-Journal & Indexed & Publishing Article Arrival : 21/12/2020 Research Article Published : 10.02.2021 Doi Number http://dx.doi.org/10.26449/sssj.3071 Atasoy, E. & Atış, E. (2021). “Minorities In The Age Of Globalization And Localization: The Vlach Community In Bulgaria From The Reference Perspective Of Political And Cultural Geography” International Social Sciences Studies Journal, (e-ISSN:2587-1587) Vol:7, Issue:78; pp:629-643 MINORITIES IN THE AGE OF GLOBALIZATION AND LOCALIZATION: THE VLACH COMMUNITY IN BULGARIA FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF POLITICAL AND CULTURAL GEOGRAPHY Küreselleşme ve Yerelleşme Çağında Azınlıklar: Siyasi ve Kültürel Coğrafya Perspektifinden Bulgaristan’daki Ulah Topluluğu Prof. Dr. Emin ATASOY Bursa Uludag University, Faculty of Education, Bursa/Turkey ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6073-6461 Asst. Prof. Evren ATIŞ Kastamonu University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Department of Geography, Istanbul/Turkey ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5686-3169 ABSTRACT Wallachs (Vlachs or Wallachians) are one of the most multiple minorities living on the territory of Bulgaria. This ethnos has its own colourful cultural, political and social, folklore and historical characteristics, which distinguish it from the other ethnic groups in the country. In this scientific work we are only going to dwell on some ethno-geographical and socio-cultural characteristics of Wallachs in Bulgaria, as well as to reflect some different scientific viewpoints and positions of various Bulgarian authors and researchers of Wallachian ethnos. Some significant topics discussed in this work are: history of Wallachian population in Bulgaria; political and ethno-cultural attitude of the Bulgarian state towards Wallachs; geographical distribution and number of Wallachian population in Bulgaria, and their socio-cultural characteristics. -

54 Un Dramaturg Din ,,Provincie” Către Centru: Victor Cilincă Asist. Univ. Dr

Un dramaturg din ,,provincie” către centru: Victor Cilincă Asist. univ. dr. BOTEZATU Elena Universitatea „Dunărea de Jos” din Galați Abstract: The dramatic works by Victor Cilincă (born on January 15, 1958 in Pașcani, Iași County) display an obvious intention of nearing the “grand texts” of world literature, in his own manner, of course, by anchoring the view in “the present lived”. Out of the many titles which make up the playwright’s complete works ascribable to the aforesaid grid, one could mention: O scrisoare…. Găsită [A… Found Letter], Dulcețuri și otrăvuri sau Dʼale Caragialelui [Sweets and poisons, or Caragialesques], Generalul generalilor [The Generals’ General] – with another version, Waiting for… Godeaux, Țara / Tzara de sub picior [The Land/ Tzara under the Foot], Romică și Jeanette or, why not, Zimbrul păcălit de vulpe [The Aurochs fooled by the Fox]. Another “dialogue” constructed around a character, around a dominating human type, can be established between Cilincă’s play Paparazzi and the homonymous play by Matei Vișniec. The parallel analysis of the two plays relies on observing the “relation between texts” and the way in which the figure of the journalist is outlined by the two playwrights. Keywords: drama, patterns, “dialogue of texts”, centre, periphery. Născut pe data de 15 ianuarie 1958 la Pașcani, județul Iași, stabilit ulterior la Galați, despre Cilincă se poate spune că este un autor din „provincie”, dar unul mândru de „nestrămutarea sa”10. După cum însuși mărturisește, prin anii 80, găsea până și Bucureștiul a fi undeva „departe și foarte sus”, crezând că pentru a viza capitala, ca scriitor, trebuia „să fii într-o anumită zodie, specială”11.