Self-Fulfilling Prophecies and Human Rights in Canada's Foreign Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada's Parliament

Foreign Policy White Papers and the Role of Canada’s Parliament: Paradoxical But Not Without Potential Gerald J. Schmitz Principal analyst, international affairs Parliamentary Information and Research Service Library of Parliament, Ottawa Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association University of Western Ontario, London Panel on “International and Defence Policy Review” 3 June 2005 Note: This paper developed out of remarks to a conference in Quebec City in May 2004 on the subject of white-paper foreign policy management processes, and is a pre- publication draft of an article for the fall 2005 issue of Études internationales. The views expressed are the author’s alone. Please do not cite without permission. Introduction to the Paradoxical Actor on the Hill The observations that follow draw on several decades of direct experience working with that paradoxical, and sometimes overlooked, actor in the foreign policy development process, namely Canada’s Parliament. During that time concerns about the alleged weaknesses of parliamentary oversight of the executive have become a commonplace complaint. They seem also to be a staple assumption in the academic discourse on Canadian foreign policy, when the legislative role merits any mention at all. (Frequently it does not.) Yet if one believes the renewed rhetoric emanating from high places about redressing “democratic deficits” in the Canadian body politic, this was all supposed to change. At the end of 2003, a new prime minister ushering in a new management regime, or at least a different style of governing, said that he and his government were committed to changing the way things work in Ottawa. -

A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993

Canadian Military History Volume 24 Issue 2 Article 8 2015 A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 Greg Donaghy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Greg Donaghy "A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993." Canadian Military History 24, 2 (2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 GREG DONAGHY Abstract: Fifty years ago, Canadian peacekeepers landed on the small Mediterranean island of Cyprus, where they stayed for thirty long years. This paper uses declassified cabinet papers and diplomatic records to tackle three key questions about this mission: why did Canadians ever go to distant Cyprus? Why did they stay for so long? And why did they leave when they did? The answers situate Canada’s commitment to Cypress against the country’s broader postwar project to preserve world order in an era marked by the collapse of the European empires and the brutal wars in Algeria and Vietnam. It argues that Canada stayed— through fifty-nine troop rotations, 29,000 troops, and twenty-eight dead— because peacekeeping worked. Admittedly there were critics, including Prime Ministers Pearson, Trudeau, and Mulroney, who complained about the failure of peacemaking in Cyprus itself. -

Canada and the Kosovo Crisis: an Agenda for Intervention

Canada and the Kosovo Crisis: An Agenda for Intervention Canada and the Kosovo Crisis: An Agenda for Intervention Michael W. Manulak Centre for International Relations, Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada 2011 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Manulak, Michael W., 1983- Canada and the Kosovo crisis : an agenda for intervention / Michael W. Manulak. (Martello papers, ISSN 1183-3661 ; 36) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-55339-245-3 1. Kosovo War, 1998-1999—Participation, Canadian. 2. Canada— Military policy. I. Queen’s University (Kingston, Ont.). Centre for International Relations II. Title. III. Series: Martello papers ; 36 DR2087.6.F652C3 2010 949.7103 C2010-907064-X © Copyright 2011 Martello Paper Series Queen’s University’s Centre for International Relations (QCIR) is pleased to present the latest in its series of monographs, the Martello Papers. Taking their name from the distinctive towers built during the nineteenth century to defend Kingston, Ontario, these papers cover a wide range of topics and issues in foreign and defence policy, and in the study of international peace and security. How governments make decisions in times of crisis is a topic which has long fascinated both theorists and practitioners of international politics. Michael Manulak’s study of the Canadian government’s decision to take part in NATO’s use of force against Serbia in the spring of 1999 deploys a novel social-scientific method to dissect the process whereby that decision was made. In that respect this paper descends from a long line of inquiry going back to the 1960s and the complex flow-charts designed by “scientific” students of foreign policy. -

September 16, 2020 Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People’S Republic of China Wang Yi

September 16, 2020 Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China Wang Yi Re: The Immediate Release of and Justice for Dr Wang Bingzhang Dear Minister Wang Yi, We write to bring to your attention the dire situation of Dr Wang Bingzhang, a Chinese national with a strong Canadian connection languishing in solitary confinement in Shaoguan Prison. In 1979, the Chinese Government sponsored Dr Wang’s studies at McGill University’s Faculty of Medicine. In 1982, Dr Wang became the first Chinese national to be awarded a PhD in North America. Newspapers in China and around the world praised his monumental accomplishments. Dr Wang then decided to forego his promising career in medicine to dedicate his life to human rights, firmly believing that self-sacrifice for his country was the most noble value. He identified as a Chinese patriot, and should have returned home a hero. Instead, in 2002, he was kidnapped in Vietnam and forcibly brought to China. It was only after five months of incommunicado detention that he was notified of the charges brought against him. Not once was he permitted to contact his family or a lawyer. At trial, Dr Wang was denied the opportunity to speak or present evidence, and no credible evidence or live witness testimony was presented against him. Moreover, the trial was closed to the public and lasted only half a day. The Shenzhen People’s Intermediate Court sentenced Dr Wang to life in solitary confinement. Dr Wang appealed the decision, but the sentence was upheld a month later, where he was again barred from speaking. -

A Reformed Senate As a Check on Prime Ministerial Power

A Reformed Senate as a Check on Prime Ministerial Power by Evan Sotiropoulos One problem of Canadian parliamentary democracy is the concentration of power in the hands of the Prime Minister and the ascendancy of the Prime Ministers Office over Parliament. This article looks at some of the reasons for the weakness of the House of Commons vis à vis the Prime Minister. It then looks at the Senate and the place a reformed Senate may have in acting as a counterweight to a system that has been transformed from executive centred to prime ministerial dominated. n a representative democracy, individuals are elected democracy, but should these traditions serve to restrict Ito “represent” the views of the citizenry and, in debate and circumvent the duty of an elected theory, meet in a common place to actually debate representative to question certain conclusions and even public policy. Although the practice of politics is partake in the decision making process? commonly divorced from the theory, the current rift A matter of consternation among MPs is the fact that between the two should concern all Canadians. It should “the rules on what constitutes a government defeat are be noted that as national elections become increasingly vague and hence flexible … [since] an important matter leader-centric, most candidates at the local level pin their remains subject to dispute”3. political aspirations on the performance of their party Liberal Party regimes – including the three under with the hope of punching their ticket to Parliament. Chrétien – would regularly muzzle backbenchers by de- Therefore, when those green seats are distributed in claring various non-money bills matters of confidence. -

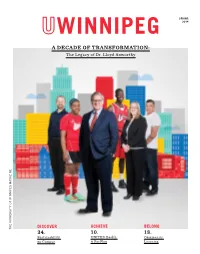

A DECADE of TRANSFORMATION —INSIDE & out the Legacy of Dr

SPRING WINNIPEG 2014 A DECADE OF TRANSFORMatION: The Legacy of Dr. Lloyd Axworthy DISCOVER ACHIEVE BELONG THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG MAGAZINE 34. 10. 18. Sustainability UNITED Health Community on Campus & RecPlex Learning Reward yourself. Get the BMO® University of Winnipeg MasterCard.®* Reward yourself with 1 AIR MILES®† reward mile for every $20 spent or 0.5% CashBack® and pay no annual fee1,2. Give something back With every purchase you make, BMO Bank of Montreal® makes a contribution to help support the development of programs and services for alumni, at no additional cost to you. Apply now! 1-800-263-2263 Alumni: bmo.com/winnipeg Student: bmo.com/winnipegspc Call 1-800-263-2263 to switch your BMO MasterCard to a BMO University of Winnipeg MasterCard. 1 Award of AIR MILES reward miles is made for purchases charged to your Account (less refunds) and is subject to the Terms and Conditions of your BMO MasterCard Cardholder Agreement. The number of reward miles will be rounded down to the nearest whole number. Fractions of reward miles will not be awarded. 2 Ongoing interest rates, interest-free grace period, annual fees and all other applicable fees are subject to change. See your branch, call the Customer Contact Center at 1-800-263-2263, or visit bmo.com/mastercard for current rates.® Registered trade-marks of Bank of Montreal. ®* MasterCard is a registered trademark of MasterCard International Incorporated. ®† Trademarks of AIR MILES International Trading B.V. Used under license by LoyaltyOne, Inc. and Bank of Montreal. Docket #: 13-321 Ad or Trim Size: 8.375" x 10.75" Publication: The Journal (Univ of Winnipeg FILE COLOURS: Type Safety: – Alumni Magazine) Description of Ad: U. -

The Liberal Third Option

The Liberal Third Option: A Study of Policy Development A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fuliiment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science University of Regina by Guy Marsden Regina, Saskatchewan September, 1997 Copyright 1997: G. W. Marsden 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KI A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your hie Votre rdtérence Our ME Notre référence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distibute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substanîial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This study presents an analysis of the nationalist econornic policies enacted by the federal Liberal government during the 1970s and early 1980s. The Canada Development Corporation(CDC), the Foreign Investment Review Agency(FIRA), Petro- Canada(PetroCan) and the National Energy Prograrn(NEP), coliectively referred to as "The Third Option," aimed to reduce Canada's dependency on the United States. -

312 Canadian Foreign Policy the Chrétien-Martin Years Lecture 11 POL 312Y Canadian Foreign Policy Professor John Kirton University of Toronto

312 Canadian Foreign Policy The Chrétien-Martin Years Lecture 11 POL 312Y Canadian Foreign Policy Professor John Kirton University of Toronto Introduction: The Chrétien-Martin Eras Assessed In interpreting Canadian foreign policy during the Chrétien-Martin years, scholars face unusual difficulty (Smith 1995). Unlike Pierre Trudeau and Kim Campbell before him, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien did not set forth during his earlier life, his first election campaign, or his first year in office a comprehensive personal vision of what his foreign policy would be. His definitive “Statement” on foreign policy, unveiled on February 7, 1995, appeared to have been overtaken within a year by a very different doctrine from his new foreign minister Lloyd Axworthy, and ultimately by the “Dialogue” report released by foreign minister Bill Graham in June 2003. Moreover, Chrétien’s foreign policy doctrines, resource distributions, and key decisions were designed at the start to deal with the bright post–Cold War world abroad and the grim world of deficits, debt, and disunity at home. But by the end of the Chrétien decade, his Liberal Party successor Paul Martin had to cope with the great reversal of a grim post 9/11 world at war abroad and a strong, secure, cohesive Canada at home. Martin’s effort to do so, in his April 2005 International Policy Statement, demonstrated the difficulties of doctrinally doing so. The Chrétien Decade: The Debate In assessing Jean Chrétien’s decade as Prime Minister from October 25, 1993 to December 12, 2003, scholars offer three major competing schools of thought. The first sees LI’s disappointing continuity, as once again the prospect of immediate change from a new prime minister was quickly snatched away. -

Canada's Inadequate Response to Terrorism: the Need for Policy

Fraser Institute Digital Publication February 2006 Canada’s Inadequate Response to Terrorism: The Need for Policy Reform by Martin Collacott CONTENTS Executive Summary / 2 Introduction / 3 The Presence of Terrorists in Canada / 4 An Ineffective Response to the Terrorism Threat / 6 New Legislation and Policies / 16 Problems Dealing with Terrorists in Canada / 21 Where Security Needs To Be Strengthened / 27 Problems with the Refugee Determination System / 30 Permanent Residents and Visitors’ Visas / 52 Canada Not Taking a Tough Line on Terrorism / 60 Making Clear What We Expect of Newcomers / 63 Working With the Muslim Community / 69 Concluding Comments and Recommendations / 80 Appendix A: Refugee Acceptance Rates / 87 References / 88 About the Author / 100 About this Publication / 101 About The Fraser Institute / 102 Canada’s Inadequate Response to Terrorism 2 Executive Summary Failure to exercise adequate control over the entry and the departure of non-Canadians on our territory has been a significant factor in making Canada a destination for terror- ists. The latter have made our highly dysfunctional refugee determination system the channel most often used for gaining entry. A survey that we made based on media reports of 25 Islamic terrorists and suspects who entered Canada as adults indicated that 16 claimed refugee status, four were admitted as landed immigrants and the channel of entry for the remaining five was not identified. Making a refugee claim is used by both ter- rorists and criminals as a means of rendering their removal from the country more difficult. In addition to examining specific shortcomings of current policies, this paper will also look at the reasons why the government has not rectified them. -

A Bold New Court CHRISTINA SPENCER EXAMINES the INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT on the EVE of ITS FIRST CHARGES

ROY MACLAREN • LLOYD AXWORTHY • JIM PETERSON • BELINDA STRONACH March–April 2005 ABold New Court CHRISTINA SPENCER EXAMINES THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT ON THE EVE OF ITS FIRST CHARGES LLOYD AXWORTHY LOOKS AT JUSTICE IN A POST-IRAQ WORLD Philippe Kirsch, president and top judge of the International Criminal Court What Frank McKenna takes to Washington Allan Thompson critiques Canada’s immigration policy Canada’s trade minister and his critic on trade with China Why the Commonwealth and the Francophonie still matter ESTABLISHED 1989 CDN $5.95 PM 40957514 ROY MACLAREN • LLOYD AXWORTHY • JIM PETERSON • BELINDA STRONACH March–April 2005 A Bold New Court CHRISTINA SPENCER EXAMINES THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT ON THE EVE OF ITS FIRST CHARGES LLOYD AXWORTHY LOOKS AT JUSTICE IN A POST-IRAQ WORLD Philippe Kirsch, president and top judge of the International Criminal Court What Frank McKennatakes to Washington Allan Thompson critiques Canada’s immigration policy Canada’s trade minister and his critic on the China trade Why the Commonwealth and the Francophonie still matter ESTABLISHED 1989 CDN $5.95 PM 40957514 Volume 16, Number 2 PUBLISHER Lezlee Cribb EDITOR Table of Jennifer Campbell CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Daniel Drolet CONTENTS George Abraham CULTURE EDITOR Margo Roston DIPLOMATICA| COPY EDITOR News and Culture . 3 Roger Bird Beyond the Headlines . 7 CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Recent Arrivals . 8 Lloyd Axworthy Diplo-dates . 11 Stephen Beckta Laura Neilson Bonikowsky Margaret Dickenson DISPATCHES| Chad Gaffield The International Criminal Court Comes of Age Dan Hays Setting the prosecutorial wheels in motion . 12 Daniel Jouanneau Ghazala Malik Lloyd Axworthy on being at its birth . 15 Peter Milliken Jim Peterson Canada’s new man in Washington Christina Spencer Being Frank . -

1994Report.Pdf

Academic CANADIAN HIGEI COMMISSION HAUT-COMMISSARIAT DU CANADA MACDONALD HOUSE 1 GROSVENOR SQUARE LONDON WlX OAB Tel: 071258 6691 ISSN-0269-1256 (IXNiDIAN ACADEMIC NEWSHEET No. 45 - Autumn l!J!M CM’ADA-UK RJ!ilLAmONS: Sm R?E DANCE? Report on ,the Canada-UK Colloquium Montehello, 27-30 September 1994 Introduction The Canadian Foreign Minister, the Hon Andre Ouellet, and the British Foreign Secretary, the Rt Han Douglas Hurd, addressing the recent Canada-UK Colloquium in Ottawa, spoke of the lively present of dealings between Canada and Britain, and of new energy following a traditional path. A characteristic of Canada-UK relations is the extraordinary amount of bilateral business and contacts there are, mostly unseen and unsung. The Canada- UK Colloquia are part of that “lively present”, and deserve wider recognition for the work they do in nurturing exchange between the two countries. The Canada-UK Colloquia hold annual bilateral meetings, usually on social and economic issues. Every five years, as was the case this year, the focus is on Canada-UK relations in the wider international context. The title of this year’s Colloquium was Prosperity and Stability in the International System: Canada-UK Cooperation in the Post Cold War World. The meeting was chaired by Senator Allan MacEachen, former Secretary of State for External Affairs, and currently Co-Chair of the Special Joint Parliamentary Committee reviewing Canada’s foreign policy, the report of which is due to be published in mid-November. The programme of the Colloquium is given at Annex A. The papers presented and a summary of the discussions, edited by Peter Lyon, are to be published in Spring 1995. -

A Precursor of Medicare in Canada?

Holiday Review Past progressive The Check-Off: A precursor of medicare in Canada? he public system of health care insurance that exists made from miners’ wages for a subscription to physician in Canada today was implemented nationally in 1968 services, medications and hospital care. A reference to the 0 and was greatly influenced by the 1964 Royal Com- Check-Off in minutes of the Nova Scotia Provincial Work- 5 6 T 1 0 mission on Health Services, headed by Justice Emmett Hall. men’s Association suggests that it dates from about 1883, 5 0 . j a When, in his final report, Justice Hall described the evolu- although at least one other historical reference places its m 2 c / tion of health care in Canada, he made brief reference to a origin even earlier, in the mid-19th century. It proved to be 3 0 5 1 health insurance system that existed in the Glace Bay col- a durable system, surviving in Cape Breton mining towns . 0 1 : liery district of Cape Breton. Known as the “Check-Off,” until 1969, when it was replaced by provincial medical in- I O D this was a mandatory system whereby deductions were surance administered by Maritime Medical Care. One of us (C.M.) was first introduced to the Check-Off system by a Halifax-based surgeon, Dr. Allan MacDonald, who had done some general practice locums in Glace Bay in the 1960s. He suggested an interview with Dr. Joe Roach, a veteran of the system, who at 83 was still seeing 11 000 to 12 000 patients a year and doing regular house calls.