Sumerian Beer: the Origins of Brewing Technology in Ancient Mesopotamia*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beer and Malt Handbook: Beer Types (PDF)

1. BEER TYPES The world is full of different beers, divided into a vast array of different types. Many classifications and precise definitions of beers having been formulated over the years, ours are not the most rigid, since we seek simply to review some of the most important beer types. In addition, we present a few options for the malt used for each type-hints for brewers considering different choices of malt when planning a new beer. The following beer types are given a short introduction to our Viking Malt malts. TOP FERMENTED BEERS: • Ales • Stouts and Porters • Wheat beers BOTTOM FERMENTED BEERS: • Lager • Dark lager • Pilsner • Bocks • Märzen 4 BEER & MALT HANDBOOK. BACKGROUND Known as the ‘mother’ of all pale lagers, pilsner originated in Bohemia, in the city of Pilsen. Pilsner is said to have been the first golden, clear lager beer, and is well known for its very soft brewing water, which PILSNER contributes to its smooth taste. Nowadays, for example, over half of the beer drunk in Germany is pilsner. DESCRIPTION Pilsner was originally famous for its fine hop aroma and strong bitterness. Its golden color and moderate alcohol content, and its slightly lower final attenuation, give it a smooth malty taste. Nowadays, the range of pilsner beers has extended in such a way that the less hopped and lighter versions are now considered ordinary lagers. TYPICAL ANALYSIS OF PILSNER Original gravity 11-12 °Plato Alcohol content 4.5-5.2 % volume C olor6 -12 °EBC Bitterness 2 5-40 BU COMMON MALT BASIS Pale Pilsner Malt is used according to the required specifications. -

Masonry QA Tap List 3:12

CRAFT BEER BEER CIDER DE RANKE/DUNHAM COMPLEXITÉ BELGIAN PALE 6 oz GREENWOOD SIDRA SIDRA .25L 6.5% a hoppy Belgian beer; zesty 8 6.9% an effervescent cider; sweet up front, tart on the back 8 FLENSBURGER PILS GERMAN PILSNER .5L WHITEWOOD KINGSTON BLACK, DABINETT, BROWNS .25L 4.8% sweet biscuity malt bill meets classic german noble hops 8 8.3% a bone dry cider of great complexity 8 GULDEN DRAAK SMOKE BELGIAN QUAD 6 oz 10.5% a rich, ruby hued Belgian beer; notes of sweet, smoked malt 8 HOLY MOUNTAIN BLACK BEER DARK ALE .5L 4.5% dry, roasty, & sessionable dark ale 7 WINE JESTER KING 2017 DAS WUNDERKIND SAISON 6oz BOTTLE POUR 4.5% a mixed culture, hoppy/funky farmhouse ale 6 BY THE GLASS OXBOW MONTAGE FRUITED FARMHOUSE ALE 6oz COUGAR CREST DEDICATION RED BLEND 6oz 6.5% sour & zesty ale blended w/ raspberries, oranges, & grapes 8 13.2% a rich, balanced blend of cab, merlot and syrah 14 OXBOW PLUM SYNTH FRUITED FARMHOUSE ALE 6oz PETRONI CORSE ROSÉ 6oz 7.5% a nicely tart, mixed fermentation beer with plums 10 12.5% vibrant w/ chalky minerality; strawberries & crushed flowers 12 SCRATCH BLACKBERRY CEDAR FARMHOUSE ALE 6oz PARDAS RUPESTRIS 6oz 5.5% notes of blackberries, juniper, and cedar bark 8 12% refreshing & bright, w/ lemony acidity & mineral finish 12 SCRATCH FILÉ FARMHOUSE FARMHOUSE ALE 6oz LESSE-FITCH CABERNET SAUVIGNON 6oz 4.5% a true Illinois beer, sweet sassafras and citrus notes 7 13.5% dark cherry & supple tannins profile w/ leathery nuance 13 SCRATCH MARIGOLD OAK LEAVES FARMHOUSE ALE 6oz MOOBUZZ PINOT NOIR 6oz 5% fresh, floral; like wild carnation and white oak leaves 8 13.8% red currant, dark cherry, rich mocha, w/ long, velvety finish 12 SKOOKUM TEMPLE RHYTHMS IPA .5L 6.7% juicy, hazy just the way you made me w/ a grapefruit bite 8 STILLWATER ON FLEEK IMPERIAL STOUT .25L 13% a big, rich dark beer with notes of chocolate and coffee 8 STILLWATER CELLAR DOOR SAISON 12oz NOT BOOZE 6.6% a spicy, earthy saison with white sage 8 FINCA COFFEE WAYFINDER CRUSHER DESTROYER SMOKED BOCK 16oz CAN cold brew 5 7.2% beech smoke, dried fruit, and oak. -

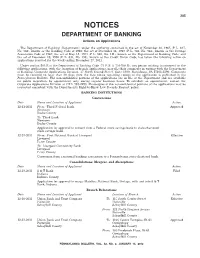

NOTICES DEPARTMENT of BANKING Actions on Applications

205 NOTICES DEPARTMENT OF BANKING Actions on Applications The Department of Banking (Department), under the authority contained in the act of November 30, 1965 (P. L. 847, No. 356), known as the Banking Code of 1965; the act of December 14, 1967 (P. L. 746, No. 345), known as the Savings Association Code of 1967; the act of May 15, 1933 (P. L. 565, No. 111), known as the Department of Banking Code; and the act of December 19, 1990 (P. L. 834, No. 198), known as the Credit Union Code, has taken the following action on applications received for the week ending December 27, 2011. Under section 503.E of the Department of Banking Code (71 P. S. § 733-503.E), any person wishing to comment on the following applications, with the exception of branch applications, may file their comments in writing with the Department of Banking, Corporate Applications Division, 17 North Second Street, Suite 1300, Harrisburg, PA 17101-2290. Comments must be received no later than 30 days from the date notice regarding receipt of the application is published in the Pennsylvania Bulletin. The nonconfidential portions of the applications are on file at the Department and are available for public inspection, by appointment only, during regular business hours. To schedule an appointment, contact the Corporate Applications Division at (717) 783-2253. Photocopies of the nonconfidential portions of the applications may be requested consistent with the Department’s Right-to-Know Law Records Request policy. BANKING INSTITUTIONS Conversions Date Name and Location of Applicant Action 12-21-2011 From: Third Federal Bank Approved Newtown Bucks County To: Third Bank Newtown Bucks County Application for approval to convert from a Federal stock savings bank to state-chartered stock savings bank. -

NSW Health Healthy Food Finder: What Are Fermented Drinks? Fermented Drinks Inlcude Kombucha, Fermented Drinks and Alcohol Ginger Beer, Kvass and Kefir

Fast facts NSW Health Healthy Food Finder: What are fermented drinks? Fermented drinks inlcude kombucha, Fermented drinks and alcohol ginger beer, kvass and kefir. Kombucha is producted from a mixture of steeped tea and sugar, combined with In response to a recent Commonwealth a culture of yeat strains and bacteria. Department of Health Report that shows the Process to list drinks on Healthy Food Finder Some kombucha drinks also have fruit presence of undeclared alcohol in some jucie or other flavours added during fermented beverage products (kombucha, The ABCL encourages Members to list production. ginger beer, kvass and kefir products), the productsby emailing the following NSW Ministry of Health has removed all documentation (developed in Kefir can be produced from milk (or a dairy alternative such as soy milk) , water kombucha, ginger beer, kvass and kefir conjunction with NSW Food Authority) to or coconut water. products from Healthy Food Finder. the Healthy Food Information Service ([email protected]). This Kvass is a traditional fermented Slavic includes products that have previously beverage commonly made from rye Healthy Food Finder been listed in the Healthy Food Finder: bread. Healthy Food Finder is a food and drink look- up tool that is used by Local Health Districts, 1. Evidence (documentation) that the retailers and canteen managers to guide alcohol content of your fermented product selection to meet the NSW Healthy product is less than 0.5% at the time For more information Food and Drink Framework or NSW Health of bottling; and FSANZ, Labelling of Alcoholic School Canteen Strategy. Health facilities Beverages User Guide, 2014 and school canteens are attended by groups 2. -

July 2018 | FREE!

Drink Read local. BEER PAPER local. beerpaperla.com /beerpaperla #beerpaperla @beerpaperla VOLUME 6 | ISSUE 2 | July 2018 | FREE! David Walker at the Firestone Walker Invitational Beer Fest Photo Credit: Nick Gingold, Craft Media L.A. BEER BEFORE GLORY By Daniel Drennon The American (Craft Beer) Revolution continues to rage like a California wildfire with now over 6000 breweries in the US and over 900 here in California. And while this uniquely American Revolution is inspiring new breweries all over the world, there is an ironic twist in that one of the most visible leaders of the country’s love affair with craft beer is not even a brewer and, well, he’s British. (FULL STORY ON PAGE 12) INSIDE BREWER’S CORNER WISHFUL DRINKING PINTS & QUOTES TOPA TOPA LADYBEER PAGE 6 PAGE 9 PAGE 16 PAGE 18 PAGE 22 The Brewers Association presents 40+ Small and Independent Craft Breweries 20+ Celebrated Chefs craft beer + food October 18-19, 2018 | L.A. Center Studios PairedLA.com PAGE 4 JULY 2018 | Beer Paper #beerpaperla BEER PAPER Beer Paper is dedicated to providing news, commentary, and education for the craft beer communities of Los Angeles, Orange County, Inland Empire and Ventura County. OWNER/PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Daniel Drennon CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Josh Cortez @belmontscraftyneighbors HEAD WRITER: Daniel Drennon @daveziol EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT TO THE EDITOR: Renee Imhoff @hashtag_hops SENIOR CONTRIBUTORS: Sarah Bennett, Tomm Carroll, John M. Verive SPECIAL CONTRIBUTORS: Harmony Sage Fried, Erin Peters ORANGE COUNTY ACCOUNTS: Brian Navarro SOUTH BAY ACCOUNTS: Paul Brauner @cbc_torrance @smogcitybeer FOUNDED BY: Aaron Carroll & Rob Wallace @craftbeerfreak Beer Paper is 100% funded by our advertisers. -

Ohio Brew Week 2019 Beer List

Ohio BREw Week 2019 Beer List ROYAL DOCKS Broneys GREAT LAKES BREWERY Devil’s Kettle ☐ Shade Tart Fruit Ale 4.6% ☐ Burning River Blood Orange ☐ Pendragon Witbier 5.3% Pale Ale 6% RHINEGEIST WILD OHIO DEVIL’S KETTLE SEVENTH SON Cheetah Lager 4.8% Peach Tea Beer 8% ☐ Dortmunder Gold Cucumber ☐ Apricoddled Apricot Sour Ale 7% ☐ American Strong Ale Ale 7.7% ☐ Peach Dodo Sour/Gose 4.4% ☐ Lager Lager 5.8% ☐ Base of Acid Golden Sour Ale 6.5% ☐ Rooby Doo Nitro nitro blonde NORTH HIGH ☐ Dortmunder Gold Jalapeno Lager ☐ Baum Fäller Vienna Lager 6% ☐ TAFTS Lager 5.8% Nellies Key Lime Ale 4.8% ☐ Berry Shandy Fruit Ale 4.2% ☐ Bourbon Barrel 9 1/2 Hours ☐ Swizzle Cider 5% ☐ ☐ Rise IPA IPA 6% ☐ Eliot Ness Amber Lager ☐ Truth IPA 7.2% Lager 6.1% Barleywine 11.9% THIRSTY DOG Burr Oak Lodge ☐ Great Lakes IPA IPA 6.5% ☐ Bourbon Barrel Demon Blood SEVENTH SON ☐ Citra Dog IPA 6.5% ☐ Holy Moses Raspberry White Imperial Stout 11% ☐ Almighty Thicket ☐ Raspberry Ale 3.9% WEASEL BOY*See online for Styles ☐ Corm’s Original Kettle Sour Saison 4.5% ☐ Buckin’ Mule Moscow Mule Ale American Lager 4.9% Ginger Ale 6.5% ☐ Brother Jon 6.3% SEVENTH SON ☐ Currant Conditions ☐ Stone Fort Ale 5% BW3 Sour Ale with Currants 7% ☐ Proliferous DIPA 8.3% MOERLEIN ☐ Scientist IPA 7% MARKET GARDEN Big Hazy N.E. IPA 6.2% ☐ DK IV Aged Blended Sour 6.6% RHINEGEIST ☐ ☐ Stone Fort Ale 5% ☐ HellaMango India Pale Ale 6.5% ☐ Brut IPA Brut IPA 5.9% ☐ Drag the Watermelons ☐ Bubbles Ale 6.2% Watermelon Lager 5% ☐ Shandy Shandy 4.5% ☐ Cat’s Eye Ohio Hopped IPL SIXTH SENSE Dunkel Lager 5.2% IPL -

2017 Big Texas Beer Fest Dallas Program.Indd

BIG TEXAS BEER FEST 2017 PARTY MAP OUTDOOR FOOD TRUCKS TEXAS BREWERIES AMERICAN BREWERIES INTERNATIONAL BREWERIES TEXAS BREWERIES BOOTH Company Name: G3 Blue Moon Brewing Company E4 Epic Brewing I6 Karbach Brewing Co. J6 Oak Highlands Brewery G4 Small Town Brewery B10 (512) Brewing Company G2 Boulevard Brewing Company Q3 FC Dallas F3 Lagunitas Brewing Company M5 Oak St Drafthouse/East Side/Dots I7 St. Killian Importing A8 3 Nations Brewing Company L12 BrainDead Brewing J9, J10 Firestone Walker, 805 Beer A1 Lakewood Brewing Company F6 Odell I8 St. Killian Importing O4 903 Brewers K2 Breckenridge F9 Founders Brewing G7 Lazy Magnolia E7 Ommegang, Duvel I4 Stella Artois F4 Ace Premium Craft Cider H5 Brooklyn Brewery C4 Four Bullets Brewery F5 Left Hand Brewing Co. L9 On Rotation H10 Stone Brewing C6 Adelbert’s Brewery G5 Bruery E1 Four Corners Brewing Co. K10 Legal Draft Beer Co. F2 Oskar Blues Brewery J3 Sublime Imports, LLC B2 Alamo Beer Co. Q4 BTBF Merchandise F1 Franconia Brewing G8 Leinenkugel Brewing Company L2 Panther Island Brewing E10 SweetWater Brewing H7 Alaskan Brewing Co. B4 Buffalo Bayou Brewing Q2 Free Play D4 Locust Cider A7 Pedernales Brewing Company P4 Swisher Sweets G6 Alesmith K11 Cedar Creek Brewery H2 Full Sail Brewing O3 LUCK at Trinity Groves C1 Peticolas Brewing Company B8 Texas Ale Project J2 Alltech Lexington N2 Chocolate Moonshine G9 Funkwerks L6 Malai kitchen O1 Purdy Gurl Boutique C8 The Stein Shoppe A3 Argus Cidery L10 Collective Brewing Project M2 Geeks Who Drink L11 Manhattan Project Beer Company A2 Rabbit Hole Brewing H1 Traveler Beer Company K1 Armadillo Ale Works B6 Community Beer Company K6 Good Neighbor Brews L1 Martin House Brewing Co A6 Rahr & Sons Brewing Company B7 True Vine Brewing Company J4 Asahi Beer USA K7 COOP Ale Works J1 Goose Island L3 McKenzie’s Hard Cider D1 Revolver Brewing L7 TUPPs Brewery B9 Audacity Brew House O2 Dallas Caramel Company A10 Gordon Biersch Brewery of Texas J5 Merchant du Vin N3 Roadie C2 Twin Peaks Brewing Co. -

Quality Changes of Naturally Fermented Kvass During

FOODBALT 2014 QUALITY CHANGES OF NATURALLY FERMENTED KVASS DURING PRODUCTION STAGES Ivo Lidums, Daina Karklina, Asnate Kirse Department of Food Technology, Faculty of Food Technology, Latvia University of Agriculture, Liela Street 2, Jelgava, Latvia, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Commercially available beverages sold as kvass are kvass drinks and malt extract drinks, made by diluting grain extract concentrates with water and adding colourings, different flavours and artificial sweeteners. Kvass quality parameters are defined by the Regulation No 926/2010 Quality and classification requirements for kvass and kvass (malt) beverage of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Latvia Naturally fermented kvass is made from rye bread rusks without additional additives. The aim of this research was to assess the quality changes of naturally fermented kvass during production stages. Experiments were carried out at the Latvia University of Agriculture Department of Food Technology. Dry matter (refractometer, ISO 6496), active acidity (LVS EN ISO 10523:2012) and sensory properties (25 panellists; line scale ISO 4121:2003) were analysed in kvass samples during production stages. During fermentation stage of naturally fermented kvass, pH drops from 4.08 to 3.77 and in later production stages pH is between 3.82 and 3.88, pH levels do not exceed the index values of the Regulation of the Cabinet of Ministers. Relative dry matter content reduced from 5.96% to 4.94%. Sensory evaluation showed that the intensity of flavour, aroma and acidity was most pronounced in kvass sample C (total production time 156 h), however, colour was most pronounced in kvass sample A (total production time 36 h). -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Beer Production and Beer

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Beer Production and Beer Judge in United States A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Applied Statistics by Yi Hu 2019 c Copyright by Yi Hu 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Beer Production and Beer Judge in United States by Yi Hu Master of Applied Statistics University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Yingnian Wu, Chair The goal of this thesis is to analyze the current beer market in U.S. according to the manufacturing data. It will also give insights into beer judgement based on consumers' reviews. This thesis presents the market trends for producers and summarizes evaluations for beer lovers. ii The thesis of Yi Hu is approved. Rick Schoenberg Nicolas Christou Yingnian Wu, Committee Chair University of California, Los Angeles 2019 iii Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Beer Manufacture Output in U.S. 2 2.1 Intro to Production and Exports Data . .2 2.2 Total Volume of Production . .3 2.2.1 Time Series Analysis . .3 2.2.2 Stationary Analysis . .5 2.2.3 Forecasts . .6 2.3 The Volume of Production in Bottles and Cans . .6 2.3.1 Time Series Analysis . .6 2.3.2 Stationary Analysis . .7 2.4 The Volume of Production in Kegs . .8 2.4.1 Time Series Analysis . .8 2.4.2 Stationary Analysis . .9 2.4.3 Correlation between the vol. of Bottles & Cans and the vol. of Kegs .9 2.5 The Volume of Exports . 10 2.6 End-of-Month Stocks and the Consumption Volume in U.S. -

BEER FLIGHT $24 Sampler of Eight Loma Beers

BEER FLIGHT $24 Sampler of eight Loma beers boys club warren peace Middle out midnight idol American Lager Kölsch Vienna Lager Black Lager ABV: 4.3% IBU: 13 SRM: 3.2 FG: 2.6 ABV: 4.9% IBU: 25 SRM: 3.8 FG: 2.7 ABV: 4.5% IBU: 30 SRM: 10.8 FG: 3.2 ABV: 4.8% IBU: 26 SRM: 23.7 FG: 3.7 Grist: Pilsner, Flaked Corn, Flaked Rice Grist: Pilsner, Vienna, Pale Wheat Grist: Vienna, Pilsner, Munich I, Munich Grist: Pilsner, Munich I, Carafe Special II Hops: Tettnanger Hop: Hallertauer Mittelfrüh II, Carafa Special II Hops: Hallertaur Mittelfrüh Ales have been brewed in the US with Kölsch is one of the few traditional Ger- Hops:Tettnanger, Hallertauer Mittelfruh Black lager or Schwarzbier dates back to adjuncts, like corn, since the late 16th man ales still brewed in Germany today. In Vienna lager is one of the few beer styles the 14th century in southern Germany. century, but it was German immigrants response to the lager revolution in the late with documented origins that can be Centuries before refrigeration, this beer that started to use the local ingredients 1800s, the brewers in Cologne started to traced back to the first brewer to ever was fermented cool in deep caves to give it to make pale lagers similar to what they lighten the beer using modern pale malt make it: Anton Dreher in 1841. Dreher a smooth, rich, low ester profile from the made in Europe. Rice became a popular and smooth it out using new lagering tech- and his contemporary, Gabriel Sadlmayer yeast. -

Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences

ISSN: 0975-8585 Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences Identification Of Soft Drinks And Kvass Fermentation Drinks. Michail N Eliseev*, and Olga M Alexeyeva. Doctor of technical sciences professor Candidate of economic sciences Plekhanov Russian University of Economics (Stremyanny lane, 36, Moscow, 117997, Russia) ABSTRACT Kvass is the national fermentation drink. It has growing popularity both from consumers and manufacturers in most countries, and as a national Russian brand it is needed in protection of the authenticity and compliance according to the state standards. This protection also includes the intellectual property protection. Small businesses began to show special attention to its production. Kvass popularity and praise of its consumer properties, give rise to opportunities to create not only real drink, but also imitation forms of soft drinks with preservatives, food dyes, sugar and flavorings (Eliseev & Alexeyeva, 2017). Keywords: identification, Kvass, Components, Fermentation, Amino acids, Chromamoto-mass spectroscopy. *Corresponding author May–June 2018 RJPBCS 9(3) Page No. 697 ISSN: 0975-8585 INTRODUCTION Functional food is a new direction in the science of nutrition. Nutrition development includes theoretical foundations development, production, sale and consumption of functional foods. In some countries, development of functional foods and beverages is highly important process. Functional food is the most comfortable, natural form of saturation and enrichment the human body with micronutrients, as vitamins, minerals and other useful components. Bread kvass is a product of heterofermentative fermentation of alcoholic and (or) lactic acidic wort. Amino acids in kvass are formed as a result of hydrolysis of proteins in the process of mashing rye fermented malt with unmalted grain products and fermentation of leavened wort. -

History V. Stories

History v. Stories • Grandma’s quilt • Our brains on stories: meaning • Historians or journalists • Never easy • Connecting the dots • We need to get this right! Bad Information • Beer history very specialized • Blame the marketing guys, too • Internet’s helping…or not • Question authority and everything! We Like Simple Answers • Style guidelines a modern thing • Always a lot of variability… • …especially the further back you go • Styles always have a context that changes by time and place The Literature • Period books; many online • Trade journals • General journalism, too • Technical works reliable • Popular accounts suspect Research • Academic papers • Experimental archaeology • Visuals can be rich, independent information source Kvass in Livonia, c. 1880 Visual Sources and Tools • Labels and advertising materials • Antique prints • Illustrations in books and articles • Paintings • Physical objects Early Hydrometer • German, c. 1800 • Shows: • Starckbier 1.033 (?) • Mittelbier • Tischbier • Schwach Bier Ancient Boot • Ancient Persia • c. 500 BCE! Answers or Questions? • I’ll have some of each for you today • Some of these are BIG problems • Usually, reality more interesting anyway • Mark Twain: • “History doesn’t repeat, but it does rhyme.” Many Early Mysteries • Hopped beer invented in Lombardy? • What the hell was gruit? • …and how did people drink that stuff? • Always: What did it taste like? English Porter • “Three threads” blends probably true • Spurious story about R. Harwood: • Magazine article, c.1770 • “Porter” name 1725 •