Trade Marks Inter Partes Decision (O/115/11)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zivame Dot Com

+91-9731359197 Zivame Dot Com https://www.indiamart.com/zivame/ Zivame is India’s premier online lingerie store, featuring over 2000 lingerie styles to choose from:bridal lingerie, plus size lingerie, every day wear, shapewear, leisure ... About Us Zivame is India’s premier online lingerie store, featuring over 2000 lingerie styles to choose from:bridal lingerie, plus size lingerie, every day wear, shapewear, leisure wear, nightwear andswimwear for women. The collection is curated and hand-picked from the top national and international brands like Enamor, Wonderbra, Triumph, Ultimo, Lovable, Plié, Jockey, Amanté, Bw!tch, Curvy Kate, Hanes and many others. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/zivame/aboutus.html APPAREL P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Work Out Crop Top Moonbasa Flowy Shirt With Scarf Moonbasa Flower Sleeves Moonbasa Hidden Lace Cowl Cowl Neck Top Top NIGHTWEAR P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Coucou Cotton Soft Coucou Light Cotton Cozy Sleeveless Top Sleep Tee Coucou Cotton Snug Fit Sleep Shirts Racerback Sleep Tee-Pink PANTIES P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Penny Medium Coverage Penny Luxurious Lace Trim Cotton Hipster Brief Hipster Brief Penny Cotton Soft Rushed Penny Plus High Waist Full Bikini Brief Coverage Brief-Black SHAPEWEAR P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Bust Shaping Bust Shaping Smoothening Penny Plus High Waist Full Coverage Brief-Beige BRAS P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Coverage Wirefree Bra Coucou Soft Cup Full Coverage Wired Bra Lovable Youthful Seamless Wide Strap T-shirt Bra Underwired Demi Cup Bra OTHER PRODUCTS P r o d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Enamor Reversible Multiway Enamor Tropical Flora Bra Balconette Bra Enamor High Coverage FIT Curve Shaping Camisole Double Layered Bra P r o OTHER PRODUCTS: d u c t s & S e r v i c e s Moonbasa Cascading Lace Sleep Shirts Top Biara Mid Rise Bikini Biref Jockey Seamfree High Waist Tummy Shaping Brief F a c t s h e e t Year of Establishment : 2000 Nature of Business : Manufacturer CONTACT US Zivame Dot Com Contact Person: Ajay Kumar No. -

Michelle Mone and MJM International

OnLine Case 9.3 Michelle Mone and MJM International MJM International, the business started by Michelle Mone, is in the lingerie business, albeit focused on selected niches. Michelle left school in Glasgow at the age of 15 to become a fashion model. Her father had been confined to a wheelchair, paralysed by a rare blood disorder, and she wanted to help out with family finances. She was brought up in a one-bedroom tenement and the family were relatively poor. Earlier she had made money from newspaper rounds - taking on the responsibility for a number of rounds and sub- contracting the work - and distributing an Avon catalogue through school. Although she ‘always wanted her own business, telling her teachers she planned to be an entrepreneur when she barely understood the word’, she moved on from being a model to work for a brewery and became head of sales and marketing. When she was made redundant in 1996, she was 24 years old and a mother of two. Supported and encouraged by her husband, Michael, a stockbroker, she started marketing silicone breast enhancers under licence from an American manufacturer. They still work together in the business, although Mone has been known to point out that many husband and wife businesses end up failing! Her heart was in this business - not wafer thin herself, she was always complaining about not being able to find comfortable bras to wear on formal occasions. ‘They were so uncomfortable because they were designed by men’. Unlike a number of other entrepreneurs who have seen opportunities in distributing lingerie products manufactured by the leading brand owners, often via the Internet, it was always Michelle’s intention to design her own products and have them manufactured for her. -

Latin Derivatives Dictionary

Dedication: 3/15/05 I dedicate this collection to my friends Orville and Evelyn Brynelson and my parents George and Marion Greenwald. I especially thank James Steckel, Barbara Zbikowski, Gustavo Betancourt, and Joshua Ellis, colleagues and computer experts extraordinaire, for their invaluable assistance. Kathy Hart, MUHS librarian, was most helpful in suggesting sources. I further thank Gaylan DuBose, Ed Long, Hugh Himwich, Susan Schearer, Gardy Warren, and Kaye Warren for their encouragement and advice. My former students and now Classics professors Daniel Curley and Anthony Hollingsworth also deserve mention for their advice, assistance, and friendship. My student Michael Kocorowski encouraged and provoked me into beginning this dictionary. Certamen players Michael Fleisch, James Ruel, Jeff Tudor, and Ryan Thom were inspirations. Sue Smith provided advice. James Radtke, James Beaudoin, Richard Hallberg, Sylvester Kreilein, and James Wilkinson assisted with words from modern foreign languages. Without the advice of these and many others this dictionary could not have been compiled. Lastly I thank all my colleagues and students at Marquette University High School who have made my teaching career a joy. Basic sources: American College Dictionary (ACD) American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (AHD) Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (ODEE) Oxford English Dictionary (OCD) Webster’s International Dictionary (eds. 2, 3) (W2, W3) Liddell and Scott (LS) Lewis and Short (LS) Oxford Latin Dictionary (OLD) Schaffer: Greek Derivative Dictionary, Latin Derivative Dictionary In addition many other sources were consulted; numerous etymology texts and readers were helpful. Zeno’s Word Frequency guide assisted in determining the relative importance of words. However, all judgments (and errors) are finally mine. -

Estta272541 03/17/2009 in the United States Patent And

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA272541 Filing date: 03/17/2009 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91183558 Party Plaintiff Temple University -- Of the Commonwealth System of Higher Education Correspondence Leslie H Smith Address Liacouras & Smith, LLP 1515 Market Street, Suite 808 Philadelphia, PA 19102 UNITED STATES [email protected] Submission Motion for Summary Judgment Filer's Name Leslie H Smith Filer's e-mail [email protected] Signature /Leslie H Smith/ Date 03/17/2009 Attachments TEMPLE WORKOUT GEAR SJ Motion with Exhibits and Certif of Service.pdf ( 75 pages )(1933802 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD In the Matter of Application No. 77/038246 Published in the Official Gazette on December 18, 2007 Temple University – Of The Commonwealth: System of Higher Education, : : Opposer, : Opposition No. 91183558 : v. : : BCW Prints, Inc., : : Applicant. : SUMMARY JUDGMENT MOTION OF OPPOSER TEMPLE UNIVERSITY – OF THE COMMONWEALTH SYSTEM OF HIGHER EDUCATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………… 2 II. UNDISPUTED FACTS……………………………………………………… 3 III. THE UNDISPUTED FACTS ESTABLISH A LIKELIHOOD OF CONFUSION BETWEEN THE TEMPLE MARKS AND OPPOSER’S TEMPLE WORKOUT GEAR (AND DESIGN) TRADEMARK…………… 7 A. Likelihood of Confusion is a Question of Law Appropriate for Summary Judgment………………………………………………………………….. 7 B. Under the du Pont Test, the Undisputed Facts Establish A Likelihood of Confusion between Temple’s TEMPLE Marks and Opposer’s TEMPLE WORKOUT GEAR (and design) Mark…………………………………… 7 1. The TEMPLE Marks and the TEMPLE WORKOUT GEAR (and design) Mark Are Similar in Appearance, Sound, Connotation, and Commercial Impression………………………… 8 2. -

Intimates a Supplement to WWD July 2009

WWD intimates A Supplement to WWD July 2009 n RomanticR i ffantasiesi come true with spring’s Victorian- infl uenced lingerie. wINTa001B;9.indd 1 7/17/09 4:27:54 PM WWD intimates ®The retailers’ daily newspaper Published by Fairchild Publications Inc., a subsidiary of Advance Publications Inc., 750 Third Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10017 EDWARD NARDOZA Editor in Chief BRIDGET FOLEY Executive Editor JAMES FALLON Editor RICHARD ROSEN Managing Editor DIANNE M. POGODA Managing Editor, Fashion/Special Reports MICHAEL AGOSTA Special Sections Editor BOBBI QUEEN Senior Fashion Editor KARYN MONGET News Editor, Intimates WWD.COM AMY DITULLIO, Managing Editor Bruno Navarro (News Editor); Véronique Hyland (Associate Editor, Fashion); Lauren Benet Stephenson (Associate Editor, Beauty/Lifestyle) CONTRIBUTORS LOUISE BARTLETT JESSICA IREDALE ART DEPARTMENT ANDREW FLYNN, Group Art Director SHARON BER, AMY LOMACCHIO, Associate Art Directors Courtney Mitchell, Kim Gilby, Designers Eric Perry, Junior Designer Tyler Resty, Art Assistant LAYOUT/COPY DESK PETER SADERA Copy Chief MAUREEN MORRISON Deputy Copy Chief LISA KELLY Senior Copy Editor Adam Perkowsky, Kim Romagnuolo, Sarah Protzman Copy Editors PHOTOGRAPHY ANITA BETHEL, Director John Aquino, Talaya Centeno, George Chinsee, Steve Eichner, Kyle Ericksen, Stéphane Feugère, Giovanni Giannoni, Thomas Iannaccone, Tim Jenkins, Davide Maestri, Dominique Maître, Robert Mitra, David Sawyer, Cliff Watts, Kristen Somody Whalen PHOTO CARRIE PROVENZANO, Photo Editor Lexie Moreland, Ashley Linn Martin, Photo Coordinators BUSINESS JOHN COSCIA, Editorial Business Director PATRICK MCCARTHY Chairman and Editorial Director 732-935-1100 | www.hanro.com wINTa_masthead;5.indd 2 7/17/09 1:57:21 PM IN0727_p004_0CA90.indd 1 7/17/09 2:06:43 PM Introducing CONFIDENTIAL by O Lingerie. -

'I'm Not Afraid to Get My Cleavage out in Business'

The Daily Telegraph Monday 26 June 2017 *** 21 INTERVIEW Good Lord: Michelle Mone watches the Queen’s Speech while clutching her £17,000 Hermès Kelly ‘I’m not afraid to get my cleavage out in business’ THE and was made redundant by the brewing company she worked for at CELIA 24, and yet on Mone ploughed, determined to nd a niche and set up WALDEN her own business. She achieved both INTERVIEW with the invention of a silicone- padded push-up bra that didn’t leave ARNSTEIN SVEN you writhing in agony at the end of a Full of surprises: Michelle Mone – now Baroness Mone of Mayfair – has overcome bereavement, poverty and personal drama, and is now launching a global interiors business night out. It spawned an empire – and helped her amass an estimated That she should tone things down a there will be words they use in the losses. I wouldn’t be scared to take any has to do too. She is a modern £50 million fortune. “Remember that bit? “Just the rst few weeks. And my Lords that I don’t understand, and I’ll of them on, but I discovered that being Margaret Thatcher and, although Despite taking a lm Joy with Jennifer Lawrence?” she wardrobe has changed quite a bit.” have to get my iPhone out and look in politics is a no-win situation. Just this will surprise people, I was really says, referring to the story of Joy It’s clear that the Lords intimidate them up. But I’m learning more every look at what has happened to Theresa inspired by Thatcher.” That is seat in the House of Mangano, the American Miracle Mop Mone more than the boardroom ever day and I’m passionate about a lot of May.” surprising. -

Australian Official Journal Of

Vol: 22 , No. 1 3 January 2008 AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS Did you know a searchable version of this journal is now available online? It's FREE and EASY to SEARCH. Find it at http://pericles.ipaustralia.gov.au/ols/epublish/content/olsEpublications.jsp or using the "Online Journals" link on the IP Australia home page. The Australian Official Journal of Designs is part of the Official Journal issued by the Commissioner of Patents for the purposes of the Patents Act 1990, the Trade Marks Act 1995 and Designs Act 2003. This Page Left Intentionally Blank (ISSN 0819-1808) AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS 3 January 2008 Contents General Information & Notices IR means "International Registration" Amendments and Changes Application/IRs Amended and Changes ...................... 515 Registrations/Protected IRs Amended and Changed ................ 517 Registrations Linked ............................... 510 Applications for Extension of Time ...................... 515 Applications for Amendment .......................... 515 Applications/IRs Accepted for Registration/Protection .......... 18 Applications/IRs Filed Nos 1212790 to 1214456 ............................. 1 Applications/IRs Lapsed, Withdrawn and Refused Lapsed ...................................... 518 Withdrawn..................................... 518 Assignments, Transmittals and Transfers .................. 519 Cancellations of Entries in Register ...................... 521 Notices ........................................ 514 Opposition Proceedings ............................ -

Ross Stores Supplier in LA Ordered to Pay $212,000 in Back Wages

NEWSPAPER 2ND CLASS $2.99 VOLUME 72, NUMBER 10 FEBRUARY 26–MARCH 3, 2016 THE VOICE OF THE INDUSTRY FOR 71 YEARS Fred Segal, Barnabas to Move Into New Tech Enclave in Playa Vista By Andrew Asch Retail Editor Major tech companies such as Facebook and Google already have offices in Los Angeles’ Playa Vista district. Now it is time for fashion boutiques. Fred Segal will open a 20,000-square-foot space in the beachside neighborhood, probably after the 2016 holiday season, said Monica Del Borrello, a representative for the pioneering boutique retailer. The retailer will disclose more details on the space in upcoming months. Barnabas Clothing Co., another fashion retailer, is opening the last weekend of February at the exclusive Run- way retail center in Playa Vista, which is located between ➥ Playa Vista page 2 PHOTO COURTESY OF BARNABAS CLOTHING CO. NEW AT PLAYA VISTA: The Runway retail center in Los Angeles’ Playa Vista neighborhood has a movie theater, fitness studios, high-end burgers and a Whole Foods. With the opening of Barnabas Clothing Co., the retail center will get its first fashion boutique. By year end, Playa Vista is scheduled to see the opening of another fashionable retailer when Fred Segal opens a 20,000-square-foot store in the West Los Angeles community. Ross Stores Supplier Carlsbad Voters Give Thumbs Down to Caruso Mall in LA Ordered to Pay By Andrew Asch Retail Editor He has been frequently sought out as a speaker for developer In a tightly contested special election, voters in Carlsbad, Ca- seminars on the success of his malls. -

Underwear Sos!

20 40 60 80 100 20 40 60 80 100 20 40 60 80 100 20 40 60 80 100 100 100 100 UNDERWEAR SOS! £26 SARAH DAWSON SARAH FASHION FORMS SEAMLESS SEAMLESS FORMS FASHION WORDS: WORDS: IMAGE: ASOS BRA, U PLUNGE Backless? Plunging? Strapless? Don’t panic; whatever style of dress you’re rocking for the big day, we’ve got the perfect lingerie for you! PERFECT WEDDING • 75 PWM_135_75.pgs 26.05.2017 14:35 20 40 60 80 100 20 40 60 80 100 20 40 60 80 100 20 40 60 80 100 100 100 100 LINGERIE LOW-DOWN 1. 1. 2. 3. STYLISH STRAPLESS Solutions without a bra strap in sight THE PROBLEM A strapless dress, of course, means a strapless bra – but we’ve all experienced enough dodgy bras that offer zero support, create unsightly lumps and bumps and end up down by your waist by the end of the night. Not what you want on W-day. THE SOLUTION There are some fantastic strapless bras on the high street, which not 5. only hold you in place, but look pretty too – just make sure you try plenty on to fnd which one works for your shape. For more control down your back, go for a long-length bustier style, or try a strapless body – it will hold you LEVINA, ENZOANI LEVINA, in and push you up in all the right places! DRESS: 1. DREAM ANGELS MULTIWAY BRA, VICTORIA’S SECRET £56.82; 2. AUTOGRAPH LISETTE MULTIWAY PADDED BALCONY BRA, MARKS & SPENCER £25; 3. -

Utilisation of 3D Body Scanning

UTILISATION OF 3D BODY SCANNING TECHNOLOGY AS A RESEARCH TOOL WHEN ESTABLISHING ADEQUATE BRA FIT Natasha Anna Mitchell BA (hons) Student Number: 05114018 Manchester Metropolitan University Submitted in application for a Master of Science by Research award Department of Clothing Design and Technology, Hollings Campus, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, United Kingdom July 2013 ABSTRACT Natasha Mitchell Department of Clothing Design and Technology, Hollings Campus, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, United Kingdom Aims Profile the relationship and differences in bust size, position and shape in a sample of UK bra consumers using 3D anthropometric body scan data. Evaluate the presentation of bra sizing by retailers and identify areas of miss communication to characterize effective application to the bra market. Collate and validate criteria for achieving adequate bra fit and quantify the physical impact on the bust size, shape and position. Methods Three quantitative methods were applied rich data to achieve the research aims. Profiling the variation in bust size shape and positioning within a bank of 3D Body scanning data into Bust height, Breast size, Bust Spread, Breast Drop and Breast Symmetry using the 30th and 70th percentiles as category dividers. Evaluating variation found in bra sizing and fit information provided by retailers and the deviation from the British Standard guidelines and Laboratory fit trials to assess the application of retailer bra fit criteria with grades in four categories; Underband, Cup Volume, Underwire and Bra Strap to a sample of UK bra consumers. Findings The findings from this research indicate potential for 3D Body Scanning Technology as a tool to quantify the relationships and differences in five bust characteristics. -

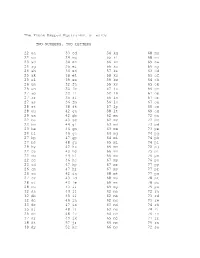

The Phone Keypad Equivalent of Words TWO NUMBERS, TWO

The Phone Keypad Equivalent of words TWO NUMBERS, TWO LETTERS 22 aa 33 ed 54 kg 68 nu 22 ac 34 eg 55 kl 68 nv 23 ad 34 eh 56 km 69 nw 24 ag 35 el 56 ko 69 ny 24 ah 36 en 57 ks 63 od 25 ak 38 et 58 ku 63 of 25 al 39 ex 59 kw 64 oh 26 am 32 fa 59 ky 65 ok 26 an 33 fe 52 la 66 on 27 ap 33 ff 52 lb 67 op 27 ar 35 fl 56 ln 67 or 27 as 36 fm 56 lo 67 os 28 at 38 ft 57 lp 69 ow 28 au 42 ga 58 lt 69 ox 29 ax 42 gb 62 ma 72 pa 22 ba 43 ge 62 mc 72 pc 22 bc 44 gi 63 md 73 pd 23 be 46 gm 63 me 73 pe 24 bi 46 go 64 mg 74 pg 27 bp 47 gp 64 mi 74 ph 27 bs 48 gu 65 ml 74 pi 29 by 42 ha 66 mm 75 pj 22 ca 43 he 66 mn 75 pl 22 cb 44 hi 66 mo 76 pm 22 cc 46 ho 67 mp 76 po 23 cd 47 hp 67 mr 77 pp 26 cm 47 hr 67 ms 77 pr 26 co 42 ia 68 mt 77 ps 27 cs 43 id 68 mu 78 pt 28 ct 43 ie 69 mx 78 pu 28 cu 43 if 69 my 79 px 32 da 44 ii 62 na 72 ra 32 db 45 il 62 nb 73 rd 32 dc 46 in 62 nc 73 re 33 de 47 is 63 nd 74 rh 35 dj 48 it 63 ne 74 ri 36 do 48 iv 64 nh 76 rn 37 dr 49 ix 65 nj 77 rr 38 dt 57 jr 66 nm 79 rx 39 dy 52 kc 66 no 72 sa Phone Number Words--Walton--Page 2 72 sc 73 sd 73 se 73 sf 76 so 78 st 79 sw 82 ta 82 tb 86 tn 86 to 88 tt 88 tv 89 tx 84 uh 85 uk 86 un 87 up 87 us 88 ut 88 uv 82 va 82 vc 83 vd 84 vi 87 vp 88 vt 92 wa 93 we 94 wi 95 wk 97 wp 98 wt 98 wv 99 wy 94 xi 98 xv 99 xx 93 yd 97 yr THREE NUMBERS, THREE LETTERS 222 aaa 222 abc 223 ace 232 ada 235 adj 232 aec 222 aba 223 abe 228 act 233 add 236 ado 235 afl Phone Number Words--Walton--Page 3 238 aft 296 awn 289 buy 288 cut 393 dye 322 fcc 243 age 293 axe 293 bye 298 cwt 327 ear 332 fda 246 ago -

HOW to MEASURE YOURSELF Able at Most Lingerie Retailers

BITEBRA dress, you have the option of going for a corset or a multi-way bra avail- HOW TO MEASURE YOURSELF able at most lingerie retailers. They have interchangeable straps, which YOUR BRA SIZE mean that you can wear it with a one- Measure in inches around your back and under shoulder, strapless, crossed back, your breast. Hold tape firmly but not tightly. halter, or low-back dress. If your measurement is an even number add 4 and if it’s an odd number add 5. SLEEVELESS GOWNS It’s important to ensure that you The resulting number is your bra size avoid side spillage, which could hap- pen if you wear a wrong cup size. YOUR CUP SIZE Ensure you have good coverage by Without a bra on, measure across the fullest getting yourself fitted. Avoid the part of your bust over your nipples. Subtract embarrassment of having to pull up your bra size from the new measurement.The straps that keep falling off the shoul- balance you are left with is your cup size. Debenhams • Mel B Ultimo Lingerie Stockist Number: 08445616161 ders. Make sure the bra you buy has AA Less than 1 inch very good elasticity that won’t be too A No difference rigid or too loose or better still you B 1 inch more can buy a bra with clear plastic C 2 inches more straps. You also have the option of D 3 inches more going for a racer back bra also DD 4 inches more known as a T-strap, that way you E 5 inches more won’t have to worry about straps F 6 inches more showing up uninvited.