Paper Teplate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films

South Asian Popular Culture ISSN: 1474-6689 (Print) 1474-6697 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsap20 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard To cite this article: Dickens Leonard (2015) Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films, South Asian Popular Culture, 13:2, 155-173, DOI: 10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Published online: 23 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsap20 Download by: [University of Hyderabad] Date: 25 October 2015, At: 01:16 South Asian Popular Culture, 2015 Vol. 13, No. 2, 155–173, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard* Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India This paper analyses contemporary, popular Tamil films set in Madurai with respect to space and caste. These films actualize region as a cinematic imaginary through its authenticity markers – caste/ist practices explicitly, which earlier films constructed as a ‘trope’. The paper uses the concept of Heterotopias to analyse the recurrence of spectacle spaces in the construction of Madurai, and the production of caste in contemporary films. In this pursuit, it interrogates the implications of such spatial discourses. Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films To foreground the study of caste in Tamil films and to link it with the rise of ‘caste- gestapo’ networks that execute honour killings and murders as a reaction to ‘inter-caste love dramas’ in Tamil Nadu,1 let me narrate a political incident that occurred in Tamil Nadu – that of the formation of a socio-political movement against Dalit assertion in December 2012. -

2. a Superhit Goddess

Ganesh, lord of auspicious beginnings and father of goddess Santoshi Ma. A Superhit Goddess Jai Santoshi Maa and Caste Hierarchy in Indian Films Part One Philip Lutgendorf “Audiences were showering coins, perennials of its vast output, yet they quarter of national cinematic output) flower petals and rice at the screen constitute one of the least-studied enjoys the largest audience in appreciation of the film. They aspects of this comparatively under- throughout the Indian subcontinent entered the cinema barefoot and set studied cinema. Indeed, I will venture and beyond. Sholay (“Flames”) and up a small temple outside…. In that for scholars and critics, Deewar (“The Wall”), were both Bandra, where mythological films mythologicals have generally been heavily-promoted “multi-starrers” aren’t shown, it ran for fifty weeks. It “hard to see.” Yet DeMille’s words belonging to the then-dominant genre was a miracle”. —Anita Guha, also belie the fact that most sometimes referred to as the masala (actress who played goddess mythologicals—like most commercial (“spicy”) film: a multi-course cinematic Santoshi Ma; cited in Kabir films of any genre—flop at the box banquet incorporating suspenseful office. The comparatively few that drama, romance, comedy, violent 2001:115). have enjoyed remarkable and action sequences, and song and Genre, Film & Phenomenon sustained acclaim hence merit study dance. Both were expensive and Cecil B. DeMille’s famously both as religious expressions and as slickly made by the standards of the cynical adage, “God is box office,” successful examples of popular art and industry, and both featured Amitabh may be applied to Indian popular entertainment. -

Analysis on Director Ram's Films

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347-4564; ISSN (E): 2321-8878 Vol. 6, Issue 12, Dec 2018, 155-166 © Impact Journals ANALYSIS ON DIRECTOR RAM’S FILMS Arivuselvan. S & Aasita Bali Research Scholar, Department of Media and Communication Studies, Christ (Deemed to be University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India Received: 15 Nov 2018 Accepted: 12 Dec 2018 Published: 18 Dec 2018 ABSTRACT This case study aims to explore the expertise of a budding, yet prolific director–Director Ram. The paper goes through the work of Director Ram in the Tamil film Industry (Kattradhu Tamizh, ThangaMeengal, Taramani) and aims to focus on the content of the films directed by him. The researcher, in his paper analyzes the types and kind of movies that the director has been a part of and the different types of techniques that he adopted and executed in his films. The researcher also analyses in detail, the type of character and highlighted the multifaceted role of women as portrayed in his films. KEYWORDS: Direction, Cinematography, Protagonist, Women, Characters, Film Industry, Globalization INTRODUCTION Indian cinema has been a standout amongst the most continually developing film ventures everywhere throughout the world. The wide variety and the number of dialects that are used in the nation, make the Indian film industry standout as the leading film producing unit. Indian film is a plethora of numerous dialects, classifications, and social orders. In any case, in a multilingual nation like our own, the significant focal point of the movies is on Bollywood. It is not valid if critiques and reviewers point out that the industry is notwithstanding the pressure or competition from Hollywood. -

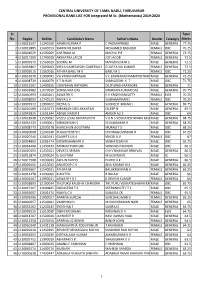

(Mathematics) 2019-2020

CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF TAMIL NADU, THIRUVARUR PROVISIONAL RANK LIST FOR Integrated M.Sc. (Mathematics) 2019-2020 Sl. Total No. RegNo RollNo Candidate's Name Father's Name Gender Cateogry Marks 1 UI10021597 11240150 ASWIN KUMAR P C PADMAPRABU MALE GENERAL 77.75 2 UI10019885 11600159 SHIRIN NILOAFER MOHAMED BASHEER FEMALE OBC 76.25 3 UI10004029 11590009 KARTHIKA M MADHU P B FEMALE GENERAL 73.75 4 UI10017309 11740028 AKSHATHA JACOB JOY JACOB FEMALE GENERAL 73.5 5 UI10009372 11560029 SOORAJ M MANOJKUMAR E MALE GENERAL 72.5 6 UI10033867 12090063 SREYA KAMESWARI GADEPALLY G SATYA SAI KUMAR FEMALE GENERAL 72.5 7 UI10005015 11560016 ATHIRA BABU M B BABU M S FEMALE OBC 72.25 8 UI10016670 11990041 V E KRISHNAPRASAD V E EASWARAN NAMPOOTHIRI MALE GENERAL 72.25 9 UI10008739 11600079 K T SHALIK SAMSUDDIN K T MALE OBC 71.75 10 UI10015367 11490256 UDAYBHAN RATHORE DILIP SINGH RATHORE MALE GENERAL 71 11 UI10033982 11070019 SOMSUVRA DAS SWADHIN KUMAR DAS MALE GENERAL 70.75 12 UI10040993 11600261 ASWATHI K K V KRISHNANKUTTY FEMALE EWS 70.25 13 UI10008003 11740122 NIVYA S V SUBRAMANIAN C FEMALE OBC 70.25 14 UI10007972 11990022 NEERAJ S SUDHEER BHANU J MALE GENERAL 69.75 15 UI10040188 11560273 NIRANJAN NEELAKANTAN DILEEP N MALE GENERAL 69.5 16 UI10043825 11601344 ABDUL NAZER E AMEER ALI E MALE OBC 69 17 UI10018938 11530092 VEZZU LEKAJ SRIHARSHITH V B N S VENKATESHWARA RAO MALE GENERAL 68.75 18 UI10055429 11090061 NIDHARSSAN S SELVAKUMAR R MALE GENERAL 68.25 19 UI10008779 12030178 M MIDHUN GOUTHAM MURALI T S MALE OBC 68.25 20 UI10020008 11240140 PUGAZHENTHI -

M.A.M . PANGALIGAL-RAYAVARAM Updated on 23 Feb 2016 Page 1 Of

M.A.M . PANGALIGAL-RAYAVARAM THIRU.PR.ADAIKKALAM, TMT. AL.VIJAYA, NO.341, D FLAT, 21, CRESCRNT AVENUE, PARK STREET, KESAVAPERUMALPURAM, RAMAKRISHNA NAGAR, CHENNAI-600 028. ALWAR THIRUNAGAR –POST, CHENNAI - 600 087. THIRU.M.ALAGAPPAN THIRU. AL.MUTHURAMAN, 5,EAST STREET, 21, CRESCENT AVENUE, THATCHAN THOTTAM, KESAVAPERUMAL PURAM, NEELIKONANPALAYAM, CHENNAI-600028 COIMBATORE-641 033 SRI.MUTHULAKSHMANAN, “VIJAYASRI”, THIRU.AR.ANNAMALAI BALAJI GARDEN, L-20,T.N.H.B COLONY, 7TH BLOCK; KANDAMPATTI, FLAT NO.3 B, FIRST FLOOR, SURAMANGALAM, V.P.G.AVENUE, METTUKKUPPAM, SALEM-636005 CHENNAI-600096. THIRU.K.ANNAMALAI THIRU.RM.ANNAMALAI NO.5,..SANTHAIPETTAI ROAD, S/O A. RAMANATHAN ARIMALAM-622 201. OLD NO.180, NEW NO.356, K.V.B.GARDEN, Cell: 9443063328. RAJA ANNAMALAIPURAM, E mail: [email protected] CHENNAI-600 028. Mr. MR.MUTHU, THIRU.R.CHELLAPPAN 19 YOGESH FLATS , S-3, SECOND FLOOR, 28, JALAN USJ 9/3 D, RENGANATHASWAMI Ist STREET, SUBANG JAYA-47620, LAKSHMIPURAM, SELANGOR, CHROMPET, MALAYSIA CHENNAI-600044. Cell No.9 600020083. THIRU.K.CHIDAMBARAM THIRU.R.CHIDAMBARAM F-2, FIRST FLOOR, 1, MAIS COURT, NEW NO.16, OLD NO.101, BATEMAN, VEERAPERUMAL KOIL STREET, WA 6150, MYLAPORE, PERTH, CHENNAI-600004 W.AUSTRALIA. THIRU.PR.CHINNAKARUPPAN THIRU.KR.CHOCKALINGAM PLOT NO:461, LAKSHMI ILLAM, BHARATHIAR MAIN STREET, 23/1, INDIRA NAGAR 17 TH STREET, K.K NAGAR AMBATHOOR- POST, MADURAI- 625020 CHENNAI-600 053. Updated on 23 rd Feb 2016 Page 1 of 11 M.A.M . PANGALIGAL-RAYAVARAM THIRU.R.A.CHOCKALINGAM, TMT. G.ALAGAMMAI ACHI, NO.4, ARUNAGIRI STREET, W/O. M.A.M.GOVINDAN CHETTIAR, KARTHIKEYAN NAGAR, NO.470, PUDUMANAI 2 ND STREET, MADURAVAYAL- PO. -

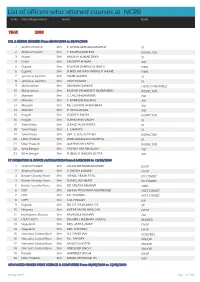

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Unit 2 Radio, Television and Cinema

UNIT 2 RADIO, TELEVISION AND CINEMA 2.0 Objectives 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Origin and Development of Radio in India 2.2.1 The Indian Broadcasting Company 2.2.2 All India Radio 2.2.3 First Three Plans 2.2.4 Chanda Committee 2.25 Code for Broadcasteis 2.2.6 Verghese Committee 2.2.7 The Present Status 1 2.2.8 Audiena Research I 2.2.9 Radio's Effectiveness 23 Origin and Deveiopment of Television in India Ii I 2.3.1 TV Comes to India 2.3.2 SITE 2.3.3 Commercial Servia I 2.3.4 National Broadcest Trust I 23.5 Development in the Eighties 2.3.6 Joshi Committee ! 2.3.7 Video Boom 2.3.8 Cable TV 2.3.9 Effectiveness of Doordarshan 2.4 Origin and Development of Films in India 2.4.1 The Beginning 2.4.2 Film mesto India 2.4.3 The Silent Era 2.4.4 The Talkie 2.4.5 Government Oiganizations 2.4.6 Need for Good Films 2.5 Let Us Sum Up 2.6 Glossary 2.7 Further Reading 2.8 Check Your Pmgms : Model Answers 2.0' OBJECTIVES After going through this unit, you should be able to : trace the development of radio, TV and film over the yeam ae a media of maw cbmrnunication; describe the reach and effectiveness of mdio, TV and film as media of mass communication; compare the development of radio, TV and film in India. 2.1 INTRODUCTION In unit 1 we traced the origin and development of the Indian press. -

Yakshagana Plays Based on Mahabharata

Yakshagana Plays Based on Mahabharata No Prasanga Name Author 1. Akshayambara Vilasa Thalengala Shambhatta 2. Anusalva Garva Bhanga matthu Niladhwajana Kalaga Ajjana Gaddhe Shankaranarayana 3. Abhaya Pradhana Dr D Sadashiva Bhatta 4. Abhimanyu Kalaga matthu Saindhava Vadhe 5. Abhimanyu Kalaga Parameshwara 6. Abhimanyu Kalaga Venkatesha V Pai 7. Ashwaththama Kiriya Balipa Narayana Bhagavatha 8. Ashwamedha Jwale Hosthota Manjunatha Bhagavatha 9. Ashwamedha Parva Kudreppadi Ishwara 10. Ashwamedha Parva Shivarama Hegade Bale Gaddhe 11. Adhiparva Sam. M. V. Hegade 12. Indrakeelaka Vishnu Ramaputra 13. Indhrakeelaka Devidasa 14. Uttharada Paurusha Puttanna, Mangalore 15. Uddhalaka Sheni Gopalakrishna Bhat [or Vishma Dampatya] 16. Ubhaya kula Billoja Bottakere Purushottama Poonja 17. Ekalavya Pandeshwara Kadappa 18. Ekalavya Hosthota Manjunatha Bhatta 19. Eni Bandhana Panduranga Ananta Shenoy 20. Airavata Parthisubba 21. Kanakangi Kalyana Nityananda Avadhoota 22. Karna Kshama Yachana Babu Kudthadka [Or Drona Senadhipatya] 23. Karna Pattabhisheka Seethanadi Ganapayya Shetty 24. Karna Parva Gerasoppe Shanth(ppa)yya 25. Karna Parva Venkatachala Bhatta,Keremane 26. Karna Ratnavathi M G Baravani 27. Karnarjunara Kalaga Venkata 28. Kitnaraja Parsango Badakabailu Parameshwarayya 29. Keechaka Vadham Naraharikeshava Bhatta, Chipageri 30. Kunti Swayamvara Seetanadhi Ganapayya Shetty 31. Kurukshetra Adura Balakila Vishnayya 32. Krishna Garudi Kota Srinivasa Nayaka 33. Krishnarjunara Kalaga Halemakkirama 34. Krishnarjunara Kalaga Mulki Ramakrishna 35. Krishnarjunara Kalaga Peruvadi Sankayya Bhagavata 36. Krishnarjunara Kalaga Balipa Narayana Bhagavata 37. Khandava Vana Dahana Ajjana Gadde Ganapayya Bhagavata 38. Gandugali Bhimasena Seetandi Ganapayya Shetty 39. Gadhaparva Subbanna Shastri, Chakrakodi 40. Gadhaparva Balipa Narayana Bhagavatha 41. Gandhari Anantaram Bangadi 42. Geetopadesha Malpe Ramadasa Samaga 43. Guru Drona Korgi Suryanarayana Upadhyaya 44. Ghatotkacha Janma M G Baravani 45. -

Born Kamal Haasan 7 November 1954 (Age 56) Paramakudi, Madras State, India Residence Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India Occupation Film

Kamal Haasan From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Kamal Haasan Kamal Haasan Born 7 November 1954 (age 56) Paramakudi, Madras State, India Residence Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India Occupation Film actor, producer, director,screenwriter, songwriter,playback singer, lyricist Years active 1959–present Vani Ganapathy Spouse (1978-1988) Sarika Haasan (1988-2004) Partner Gouthami Tadimalla (2004-present) Shruti Haasan (born 1986) Children Akshara Haasan (born 1991) Kamal Haasan (Tamil: கமலஹாசன்; born 7 November 1954) is an Indian film actor,screenwriter, and director, considered to be one of the leading method actors of Indian cinema. [1] [2] He is widely acclaimed as an actor and is well known for his versatility in acting. [3] [4] [5] Kamal Haasan has won several Indian film awards, including four National Film Awards and numerous Southern Filmfare Awards, and he is known for having starred in the largest number of films submitted by India in contest for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.[6] In addition to acting and directing, he has also featured in films as ascreenwriter, songwriter, playback singer, choreographer and lyricist.[7] His film production company, Rajkamal International, has produced several of his films. In 2009, he became one of very few actors to have completed 50 years in Indian cinema.[8] After several projects as a child artist, Kamal Haasan's breakthrough into lead acting came with his role in the 1975 drama Apoorva Raagangal, in which he played a rebellious youth in love with an older woman. He secured his second Indian National Film Award for his portrayal of a guileless school teacher who tends a child-like amnesiac in 1982's Moondram Pirai. -

ENGLISH SBI CLASS 04 APRIL 2019 the 1970S Saw a Transition in Tamil Cinema, Which Had 1

ENGLISH SBI CLASS 04 APRIL 2019 The 1970s saw a transition in Tamil cinema, which had 1. A. limited B. massive acquired enormous political and economic clout but --- C. renowned D. confine --1 artistic success. The Dravidian Movement had E. tantalizing restricted cinema to a propaganda tool and financiers 2. A. orthodox B. absurd only saw money in it. But for exceptions like Unnaippol C. aversion D. romantic Oruvan and Dikkatta Parvati, Tamil cinema was E. melodrama struggling to break free of the formula built on -----2, 3. A. evasive B. doggedly mythology, song and dance, stunts. C. realistic D. abrupt A new crop of directors then arrived and changed the E. awkward grammar of Tamil cinema. They did not reject the 4. Find error/s. market for high art, but sought a middle-ground to tell 1. A and B 2. B and C the stories of ordinary people in a/an -----3 manner. 4 J. 3. Only A 4. A and C Mahendran, the director who died aged 79 on Tuesday, 5. Only C was one such filmmaker, who had a deep influence on 5. A. lacunae B. start-up those who followed him, for instance, Mani Ratnam. C. Film D. Purview The film that made a name for Mahendran, until then E. debut a scriptwriter, was his directorial -----5, Mullum 6. A. ambitious B. antagonist Malarum. The 1978 film had an unusual hero and C. innate D. unconventional Mahendran chose an actor who was known for playing E. pragmatism the villain. The film was a runaway hit and the villain- 7. -

Hero's Journey of Mahendran's Kaali

International Journal of Research in Engineering, Science and Management 508 Volume-2, Issue-10, October-2019 www.ijresm.com | ISSN (Online): 2581-5792 Hero’s Journey of Mahendran’s Kaali (Mullum Mallarum, 1978) M. Arjun M.Sc. Student, Department of Visual Communication, Loyola College, Chennai, India Abstract: This is an attempt to deconstruct various layers of scenes were also filmed in Ooty, Tamil Nadu. Although it narrative embellishments that builds the foundation of the opened to tepid box-office earnings, positive reviews from narrative structure of Mahendran’s Mullum Malarum with the critics and favourable word of mouth in later weeks helped utilization of logical and chronological buildup of hero’s journey to understand the character arc of kaali. The findings hint that make it a success with a theatrical run of The film was noted there is a huge influence social angst that stems from the pristine and we'll received for the protagonist's performance, and traditional portrayal of the protagonist’s behaviour, but cinematography, music, and mainly Mahendran's screenplay deeper is the huge gashes of egoism we tend to witness throughout proving that cinema is a "visual medium". Mahendran’s kaali the film in the form of obsessive matriarchic behaviour and is considered to be one of the greatest characters ever penned in wrongly translates as affection and love. Kaali is portrayed as an the history of tamil cinema. It won the Filmfare Award for Best "angry young man with a kind heart" who does not admit mistakes, despite having committed acts such as breaking car Film – Tamil, the Tamil Nadu State Film Award for Best Film headlights and allowing people to ride the trolley, in violation of and Rajinikanth won the Tamil Nadu State Film Award Special, the powerhouse's rules. -

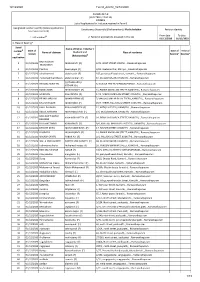

12/16/2020 Form9 AC212 16/12/2020

12/16/2020 Form9_AC212_16/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where applicaons Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Mudhukulathur Revision identy have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial Name of Father / Mother / $ Date of Date of Time of number Name of claimant Husband and Place of residence of receipt hearing* hearing* (Relaonship)# applicaon MUTHUSAMY 1 01/12/2020 MADASAMY (F) 2/22, WEST STREET, ENATHI, , Ramanathapuram MADASAMY 2 01/12/2020 Pavithra Seeniyappa (F) 2/82, Keelamunthal, Mariyur, , Ramanathapuram 3 01/12/2020 sahul hameed abdul razak (F) 102, periya pallivasal street, kamuthi, , Ramanathapuram 4 01/12/2020 mohamed thamthasin abdul rahman (F) 64, MUSLIM BAZAR, KAMUTHI, , Ramanathapuram SULTHAN ABDUL 5 01/12/2020 RISVANA PARVEEN 6, HAJIYAR STREET, SUNDARAPURAM, , Ramanathapuram KATHAR (H) 6 01/12/2020 RAMKUMAR MUNIYASAMY (F) 14, PAKKIR AMBALAM STREET, KAMUTHI, , Ramanathapuram 7 01/12/2020 SAJEEVAN SAHADEVAN (F) 14/2, PAKKIR AMBALAM STREET, KAMUTHI, , Ramanathapuram 8 01/12/2020 PRIYADHARSHINI MAARIYAPPAN (F) 2, MALUKU MALIYA PILLAI THERU, KAMUTHI, , Ramanathapuram 9 01/12/2020 BALACHANDAR MUNIYANDI (F) 15/4, PERIYA PALLIVASAL STREET, KAMUTHI, , Ramanathapuram 10 01/12/2020 HALIL RAHMAN KHAJA MAIDEEN (F) 12, ABDULLA THERU, KAMUTHI, , Ramanathapuram 11 01/12/2020 ABDUL RAHMAN MOHAMED KANI (F) C-1, MUSLIM BAZAR, KAMUTHI, ,