Tamil Cinema in the Twenty-First Century Caste, Gender, and Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Camp Sitting at Chennai, Tamil Nadu Full Commission V

NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION (LAW DIVISION – FULL COMMISSION BRANCH) CAMP SITTING AT CHENNAI, TAMIL NADU FULL COMMISSION CAUSE LIST CORAM: Mr. Justice H.L. Dattu - Chairperson Mr. Justice P.C. Pant - Member Mrs. Jyotika Kalra - Member Dr. D.M. Mulay - Member Friday, 13th September, 2019 at 10.00 A.M. Venue: Anna Centenary Library, Gandhi Mandapam Road, Surya Nagar, Kotturpuram, Chennai, Tamil Nadu S. Case No. Complainant/In Name of authority No timation received from 1. 512/22/0/2019 Suo-motu Principal Secretary, Suo-motu cognizance of a news item Labour and published in “Business Line” dated Employment (M2) 21.02.2019 highling the plight of thousands Deptt., Govt of Tamil of garmet factory workers in Tamil Nadu. Nadu 2. 896/22/37/2010 Shri Devika Chief Secretary Illegal arrest of five members of Fact Finding Prasad Director General of Team by Veeravanallur Police, Tiruneveli, Shri Henri Police Tamil Nadu Tiphagne 3. 590/22/42/2019 Shri A.P. Disitrict Collector, Complaint regarding families living without Gowdhamasidha Villupuram, Tamil Nadu shelter in Villupuram District, Tamil Nadu rthan 4. 554/22/12/2017 Shri T.D. Commissioner, Avadi Inaction by District Administration in regard Ramalingam Municipality to the complaint of stagnation of drainage District Collector and rain water in area in Awadi Municipality Tiruvallur 5. 807/22/13/2019 Shri Radhakanta The District Magistrate Complaint regarding gang-rape of a 11 year Tripathy Chennai old deaf girl in Chennai on 17.07.2018 for The Commissioner of which seventeen men were charged. Police,Chennai 6. 308/22/39/2019 Suo-motu Additional Chief Suo-motu cognizance of a news report carried Secretary Home out by “News 18” regarding sexual abuse of 15 (Pol.XII) Department, minor girls who were rescused from a Home in Tamil Nadu Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu. -

Alumni Association of MS Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences

Alumni Association of M.S. Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences (SAMPARK), Bangalore M.S. Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences Department of Automotive & Aeronautical Engineering Program Year of Name Contact Address Photograph E-mail & Mobile Sl NO Completed Admiss ion # 25 Biligiri, 13th cross, 10th A Main, 2nd M T Layout, [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive 574 2013 Pramod M Malleshwaram, Bangalore- 9916040325 Engineering) 560003 S/o L. Srinivas Rao, Sai [email protected] Dham, D-No -B-43, Near M. Sc. (Automotive m 573 2013 Lanka Vinay Rao Torwapool, Bilaspur (C.G)- Engineering) 9424148279 495001 9406114609 3-17-16, Ravikunj, Parwana Nagar, [email protected] Upendra M. Sc. (Automotive Khandeshwari road, Bank m 572 2013 Padmakar Engineering) colony, 7411330707 Kulkarni Dist - BEED, State – 8149705281 Maharastra No.33, 9th Cross street, Dr. Radha Krishna Nagar, [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Venkata Krishna Teachers colony, 571 2013 0413-2292660 Engineering) S Moolakulam, Puducherry-605010 # 134, 1st Main, Ist A cross central Excise Layout [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Bhoopasandra RMV Iind 570 2013 Anudeep K N om Engineering) stage, 9686183918 Bengaluru-560094 58/F, 60/2,Municipal BLDG, G. D> Ambekar RD. Parel [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Tekavde Nitin 569 2013 Bhoiwada Mumbai, om Engineering) Shivaji Maharashtra-400012 9821184489 Thiyyakkandiyil (H), [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Nanminda (P.O), Kozhikode / 568 2013 Sreedeep T K m Engineering) Kerala – 673613 4952855366 #108/1, 9th Cross, themightyone.lohith@ M. Sc. (Automotive Lakshmipuram, Halasuru, 567 2013 Lohith N gmail.com Engineering) Bangalore-560008 9008022712 / 23712 5-8-128, K P Reddy Estates,Flat No.A4, indu.vanamala@gmail. -

15 Sub Ptt MSB-TBM-CGL DOWN WEEK DAYS

CHENNAI BEACH - TAMBARAM - CHENGALPATTU DOWN WEEK DAYS Train Nos 40501 40001 40503 40505 40507 40701 40509 Kms Stations CJ 0 Chennai Beach d 03:55 04:15 04:35 04:55 05:15 05:30 05:50 2 Chennai Fort d 03:59 04:19 04:39 04:59 05:19 05:34 05:54 4 Chennai Park d 04:02 04:22 04:42 05:02 05:22 05:37 05:57 5 Chennai Egmore d 04:05 04:25 04:45 05:05 05:25 05:40 06:00 7 Chetpet d 04:08 04:28 04:48 05:08 05:28 05:43 06:03 9 Nungambakkam d 04:11 04:31 04:51 05:11 05:31 05:46 06:06 10 Kodambakkam d 04:13 04:33 04:53 05:13 05:33 05:48 06:08 12 Mambalam d 04:15 04:35 04:55 05:15 05:35 05:50 06:10 13 Saidapet d 04:18 04:38 04:58 05:18 05:38 05:53 06:13 16 Guindy d 04:21 04:41 05:01 05:21 05:41 05:56 06:16 18 St.Thomas Mount d 04:24 04:44 05:04 05:24 05:44 05:59 06:19 19 Palavanthangal d 04:27 04:47 05:07 05:27 05:47 06:02 06:22 21 Minambakkam d 04:30 04:50 05:10 05:30 05:50 06:05 06:25 22 Tirusulam d 04:32 04:52 05:12 05:32 05:52 06:07 06:27 24 Pallavaram d 04:35 04:55 05:15 05:35 05:55 06:10 06:30 26 Chrompet d 04:38 04:58 05:18 05:38 05:58 06:13 06:33 29 Tambaram Sanatorium d 04:41 05:01 05:21 05:41 06:01 06:16 06:36 30 Tambarm a 05:10 d 04:50 05:30 05:50 06:10 06:25 06:45 34 Perungulathur d 04:56 05:36 05:56 06:16 06:32 06:56 36 Vandalur d 04:59 05:39 05:59 06:19 06:35 06:59 39 Urappakkam d 05:03 05:43 06:03 06:23 06:39 07:03 42 Guduvancheri d 05:07 05:47 06:07 06:27 06:43 07:07 44 Potheri d 05:11 05:51 06:11 06:31 06:47 07:11 46 Kattangulathur d 05:14 05:54 06:14 06:34 06:50 07:14 47 Maraimalai Nagar d 05:16 05:56 06:16 06:36 06:52 07:16 51 Singaperumal -

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal , Free-Standing Articles Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema 2

Edinburgh Research Explorer Madurai Formula Films Citation for published version: Damodaran, K & Gorringe, H 2017, 'Madurai Formula Films', South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (SAMAJ), pp. 1-30. <https://samaj.revues.org/4359> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (SAMAJ) General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal Free-Standing Articles Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema Karthikeyan Damodaran and Hugo Gorringe Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic version URL: http://samaj.revues.org/4359 ISSN: 1960-6060 Electronic reference Karthikeyan Damodaran and Hugo Gorringe, « Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema », South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], Free-Standing Articles, Online since 22 June 2017, connection on 22 June 2017. URL : http://samaj.revues.org/4359 This text was automatically generated on 22 June 2017. -

Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Digitized Theses Digitized Special Collections 2011 CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA Ganga Rudraiah Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses Recommended Citation Rudraiah, Ganga, "CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA" (2011). Digitized Theses. 3315. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses/3315 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Special Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA r , ' (Spine title: CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by : Ganga Rudraiah Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ganga Rudraiah 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION r Supervisor Examiners Dr. Christopher E. Glttings Dr. James Prakash Younger Supervisory Committee Dr. Constanza Burucúa Dr. Chris Holmlund The thesis by Ganga Rudraiah entitled: Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Date Chair of the Thesis Examination Board Abstract The star machinery of Tamil cinema presents itself as a nearly unfathomable system that produces stars and politicians out of actors and fans out of audiences in an organized fashion. -

Psyphil Celebrity Blog Covering All Uncovered Things..!! Vijay Tamil Movies List New Films List Latest Tamil Movie List Filmography

Psyphil Celebrity Blog covering all uncovered things..!! Vijay Tamil Movies list new films list latest Tamil movie list filmography Name: Vijay Date of Birth: June 22, 1974 Height: 5’7″ First movie: Naalaya Theerpu, 1992 Vijay all Tamil Movies list Movie Y Movie Name Movie Director Movies Cast e ar Naalaya 1992 S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Sridevi, Keerthana Theerpu Vijay, Vijaykanth, 1993 Sendhoorapandi S.A.Chandrasekar Manorama, Yuvarani Vijay, Swathi, Sivakumar, 1994 Deva S. A. Chandrasekhar Manivannan, Manorama Vijay, Vijayakumar, - Rasigan S.A.Chandrasekhar Sanghavi Rajavin 1995 Janaki Soundar Vijay, Ajith, Indraja Parvaiyile - Vishnu S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Sanghavi - Chandralekha Nambirajan Vijay, Vanitha Vijaykumar Coimbatore 1996 C.Ranganathan Vijay, Sanghavi Maaple Poove - Vikraman Vijay, Sangeetha Unakkaga - Vasantha Vaasal M.R Vijay, Swathi Maanbumigu - S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Keerthana Maanavan - Selva A. Venkatesan Vijay, Swathi Kaalamellam Vijay, Dimple, R. 1997 R. Sundarrajan Kaathiruppen Sundarrajan Vijay, Raghuvaran, - Love Today Balasekaran Suvalakshmi, Manthra Joseph Vijay, Sivaji - Once More S. A. Chandrasekhar Ganesan,Simran Bagga, Manivannan Vijay, Simran, Surya, Kausalya, - Nerrukku Ner Vasanth Raghuvaran, Vivek, Prakash Raj Kadhalukku Vijay, Shalini, Sivakumar, - Fazil Mariyadhai Manivannan, Dhamu Ninaithen Vijay, Devayani, Rambha, 1998 K.Selva Bharathy Vandhai Manivannan, Charlie - Priyamudan - Vijay, Kausalya - Nilaave Vaa A.Venkatesan Vijay, Suvalakshmi Thulladha Vijay 1999 Manamum Ezhil Simran Thullum Endrendrum - Manoj Bhatnagar Vijay, Rambha Kadhal - Nenjinile S.A.Chandrasekaran Vijay, Ishaa Koppikar Vijay, Rambha, Monicka, - Minsara Kanna K.S. Ravikumar Khushboo Vijay, Dhamu, Charlie, Kannukkul 2000 Fazil Raghuvaran, Shalini, Nilavu Srividhya Vijay, Jyothika, Nizhalgal - Khushi SJ Suryah Ravi, Vivek - Priyamaanavale K.Selvabharathy Vijay, Simran Vijay, Devayani, Surya, 2001 Friends Siddique Abhinyashree, Ramesh Khanna Vijay, Bhumika Chawla, - Badri P.A. -

Heavy Vehicles Factory, Avadi, Chennai Heavy Vehicles Factory, Avadi, Chennai Scheme of Presentation

HEAVY VEHICLES FACTORY, AVADI, CHENNAI HEAVY VEHICLES FACTORY, AVADI, CHENNAI SCHEME OF PRESENTATION • About HVF and its products • Opportunities in HVF • Challenges in Indigenization. • Process of procurement. HEAVY VEHICLES FACTORY, AVADI, CHENNAI PRINCIPAL PRODUCTS 1. T-90S TANKS 2. ARJUN TANKS 3. OVERHAULING OF T-72 TANKS HEAVY VEHICLES FACTORY, AVADI, CHENNAI 4. VARIANTS OF TANK a. BRIDGE LAYER TANK (BLT) HEAVY VEHICLES FACTORY, AVADI, CHENNAI VARIANTS OF TANK CONTINUED…. b. TRAWLS HEAVY VEHICLES FACTORY, AVADI, CHENNAI BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES IN HVF There are huge opportunities for firms possessing process capabilities and expertise in • Fabrication /welding of pressed and machined components. • Manufacturing of pneumatic system operating at 150kgf/cm2 consisting of pneumatic valves. • Fabrication of pipelines of various sizes. • Manufacturing of dc motor , electromagnet with micro switches for armored fighting vehicles. • Mfg. of power, signal and data transmission cables of armored fighting vehicles. • Mfg. of electrical and electronics based control units for armored fighting vehicles. • Lamps/bulbs for armored fighting vehicles. • Mfg. Of rubber products like hoses, gaskets and seals etc. • Mfg. of castings, forgings and machined components and assemblies. HEAVY VEHICLES FACTORY, AVADI, CHENNAI CHALLENGES IN INDIGENISATION Constraints due to limited quantity. Non availability of raw material/inputs. Long lead time. Non availability of ToT. (Black box model) Non availability of design details. HEAVY VEHICLES FACTORY, AVADI, CHENNAI -

Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films

South Asian Popular Culture ISSN: 1474-6689 (Print) 1474-6697 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsap20 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard To cite this article: Dickens Leonard (2015) Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films, South Asian Popular Culture, 13:2, 155-173, DOI: 10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Published online: 23 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsap20 Download by: [University of Hyderabad] Date: 25 October 2015, At: 01:16 South Asian Popular Culture, 2015 Vol. 13, No. 2, 155–173, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard* Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India This paper analyses contemporary, popular Tamil films set in Madurai with respect to space and caste. These films actualize region as a cinematic imaginary through its authenticity markers – caste/ist practices explicitly, which earlier films constructed as a ‘trope’. The paper uses the concept of Heterotopias to analyse the recurrence of spectacle spaces in the construction of Madurai, and the production of caste in contemporary films. In this pursuit, it interrogates the implications of such spatial discourses. Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films To foreground the study of caste in Tamil films and to link it with the rise of ‘caste- gestapo’ networks that execute honour killings and murders as a reaction to ‘inter-caste love dramas’ in Tamil Nadu,1 let me narrate a political incident that occurred in Tamil Nadu – that of the formation of a socio-political movement against Dalit assertion in December 2012. -

ANNUAL REPORT June 2016 – May 2017

MOTHER TERESA WOMEN’S UNIVERSITY KODAIKANAL ANNUAL REPORT June 2016 – May 2017 Edited by : Dr.A.Muthu Meena Losini Assistant Professor Department of English Mother Teresa Women‘s University Kodaikanal Technical Assistance by : Mrs.T.Amutha Technical Assistant Department of Physics Mother Teresa Women‘s University Kodaikanal MOTHER TERESA WOMEN‟S UNIVERSITY (Accredited with „B‟ Grade by NACC) KODAIKANAL – 624 101 This is the Annual Report for the period June 2016 – May 2017 of the Mother Teresa Women‘s University, Kodaikanal. The report gives all Academic, Administrative and other relevant details pertaining to the period June 2016 – May 2017. I take this occasion to thank all the members of the Executive Council, Academic Committee and Finance Committee for all their participation and contribution to the growth and development of the University and look forward to their continued advice and guidance. Dr. G. Valli VICE-CHANCELLOR INTRODUCTION The Executive Council has great pleasure in presenting to the Academic Committee, the Annual report for the period June 2016- May 2017 as per the requirement of the section 26 of Chapter IV of Mother Teresa Women‘s University Act 1984. The report outlines the various activities which have paved for the growth and development of the University through the period June 2016 –May 2017 in the areas of Teaching, Research and Extension; it provides a detailed account of various Academic Achievements, Introduction of new Innovative Courses, Conduct of Seminar/ Workshop/ Conferences at Regional, National and International levels and its extension activities. OFFICERS AND AUTHORITIES OF THE UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR - HIS EXCELLENCY HON‘BLE Banwarilal Purohit Governor of Tamil Nadu PRO – CHANCELLOR - HONOURABLE Thiru. -

Sl. No 5 7 8 9 11 10 1 4 2 6 3 16 13 14 12 17 15 19 18

Sl. No School name & Address Catogery Research Topic Mentor name Student name Class Project title Results V. Jayashree 10 Resource Waste water and a Jai Gopal Garodia Hindu Vidyalaya Mat. Hr. Sec. School, Postal Colony, 4th Street, West N. Haritha 10 1 Junior Conservation - Mrs. N. Umaparvathy miracle Water Selected mambalam, Chennai 33 Utilization S. Lekhakanmani 9 Hyacinth R. Mahalakshmi 11 2 Senior Energy Mrs. Kaveri Hariharan S. Nivetha 11 Start - Stat Not Selected Sruthi Suresh 11 Amritha Vidyalayam, 4/9 Amman Nagar, Nesapakkam, Chennai-78 Resource Ashwin Subramanian 10 3 Junior Conservation - Mrs. Kaveri Hariharan L. Harieaaswar 10 Rice - Fish Culture Selected Utilization Shreyas Krishna Kumar 10 V. Kathiravan 9 4 Chennai High School, 53 West Coovam River Road, Chintadripet, Chennai- 02 Junior Energy D. Jeshitha Padma Sudha R. Vallarasu 9 Energy Selected S. Sabari 9 Resource Best out of Waste 5 National Public School, Gopalapuram, No 48 Poes road, Teynampet, Chennao 600018 Junior Conservation - Dr. Niranjana Shruthi Aravindan 6 Aquaponics and Selected Utilization Hydroponics Chennai High School, Arathoon Road at N.M.F No12, Ponnusamy Street, New Solid Waste A. Priyanka 9 6 Junior Mrs. K. Sasiraka Degradable Plastic Selected Washermenpet, Chennai - 81. Management J. Jenifer 9 7 Kola Saraswathi Vaishnav Senior Sec. School. Brindavan, 41, Barnaby Road, Kilpauk, Junior Resource Mr. Jayashree Aman Shah 10 Renewable Energy Not Selected Chennai - 600 010 Conservation - Aarthi Mundhra 10 Sources V. Rassi Muthu lakshmi 11 Environment Annai Velankanni's Matriculation Higher Sec School, No. 81/33, V.G.P Salai, Saidapet, S. Baktha Nandini 11 8 Senior Environment Mr. Savari Muthu James Cleanup of Coovam Selected Chennai - 15 A.S. -

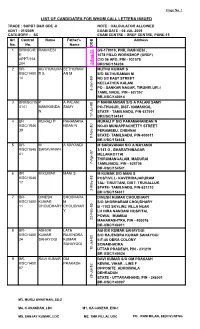

List of Candidates for Whom Call Letters Issued

Page No. 1 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR WHOM CALL LETTERS ISSUED TRADE : SUPDT B&R GDE -II NOTE : CALCULATOR ALLOWED ADVT - 01/2009 EXAM DATE - 06 JUL 2009 CATEGORY - SC EXAM CENTRE - GREF CENTRE, PUNE-15 Srl Control Name Father's Address No. No. Name DOB 1 BRII/SC/R RAM KESI GS-179019, PNR, RAM KESI , E- 1078 FIELD WORKSHOP (GREF) APPT/154 C/O 56 APO, PIN - 931078 204 3-Aug-71 BRII/SC/154204 2 BR- MUTHUKUMA SETHURAM MUTHU KUMAR S II/SC/1400 R S AN M S/O SETHURAMAN M 14 NO 5/2 EAST STREET KEELATHEN KALAM PO - SANKAR NAGAR, TIRUNELUELI 8-Jan-80 TAMIL NADU, PIN - 627357 BR-II/SC/140014 3 BRII/SC/15 P A PALANI P MANIKANDAN S/O A PALANI SAMY 4141 MANIKANDA SAMY PO-THUSUR, DIST- NAMAKKAL N STATE - TAMILNADU, PIN-637001 17-Jul-88 BRII/SC/154141 4 BR MURALI P PARAMANA MURALI P S/O PARAMANANDAN N II/SC/1546 NDAN N NO-83 MUNIAPPACHETTY STREET 38 PERAMBEU, CHENNAI STATE- TAMILNADU, PIN-600011 9-Nov-80 BR II/SC/154638 5 BR- M A MAYANDI M SARAVANAN S/O A MAYANDI II/SC/1545 SARAVANAN 3/143 G , BHARATHINAGAR 41 MELAKKOTTAI THIRUMANGALAM, MADURAI 7-Apr-87 TAMILNADU, PIN - 625706 BR-II/SC/154541 6 BR M KUMAR MANI S M KUMAR S/O MANI S II/SC/1546 POST/VILL- KAVERIRAJAPURAM 17 TAL- TIRUTTANI, DIST- TRUVALLUR STATE- TAMILNADU, PIN-631210 2-May-83 BR II/SC/154617 7 BR- DINESH SHOBHARA DINESH KUMAR CHOUDHARY II/SC/1400 KUMAR M S/O SHOBHARAM CHOUDHARY 11 CHOUDHARY CHOUDHAR B -1102 SKYLINE VILLA NEAR Y LH HIRA NANDANI HOSPITAL POWAI, MUMBAI 22-Feb-85 MAHARASHTRA, PIN - 400076 BR-II/SC/140011 8 BR- ASHOK LATE ASHOK KUMAR SAHAYOGI II/SC/1400 KUMAR RAJENDRA S/O RAJENDRA KUMAR SAHAYOGI 24 SAHAYOGI KUMAR 5-F-46 OBRA COLONY SAHAYOGI SONABHADRA 10-Jul-82 UTTAR PRADESH, PIN - 231219 BR-II/SC/140024 9 BR- RAVI KUMAR OM RAVI KUMAR S/O OM PRAKASH II/SC/1400 PRAKASH KEWAL VIHAR , LINE F 07 OPPOSITE ADHOIWALA DEHRADUN 28-Jul-82 STATE - UTTARAKHAND, PIN - 248001 BR-II/SC/140007 M3. -

FORM 11 List of Applications for Objecting to Particulars in Entries In

ANNEXURE 5.10 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 11 List of Applications for objecting to particulars in entries in electoral roll received in Form 8 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Attur Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial number Date of Name (in full) of elector Particulars of entry Nature of Date of Time of $ of receipt objecting objected at objection hearing* hearing* application Part number Serial number 1 16/11/2020 Boopathi 173 821 2 16/11/2020 Aravinthkumar 265 666 £ In case of Union territories having no Legislative Assembly and the State of Jammu and Kashmir @ For this revision for this designated location Date of exhibition at designated Date of exhibition at Electoral * Place, time and date of hearings as fixed by electoral registration officer location under rule 15(b) Registration Officer¶s Office $ Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each under rule 16(b) designated location 23/11/2020 ANNEXURE 5.10 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 11 List of Applications for objecting to particulars in entries in electoral roll received in Form 8 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Attur Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 17/11/2020 17/11/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial number Date of Name (in full)