Ournal of Law and Public Policy a Reader on Sports & Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of International Sports Events Hosted by India

List of International Sports Events Hosted by India If you are preparing for Banking & SSC Exam it is very important to prepare well for the General Awareness Section. The GA Section has a decent weightage & you can score good marks without investing much time. Nowadays, questions from Static GK are asked more than Current Affairs. Hence, it is important that you are well-versed with topics from History, Geography, Science, Environment & Sports. Read the article below that will help you with the List of International Sports Events Hosted by India & boost your exam preparation. Sports Events Hosted by India India may not be sports hub or may not be listed on the top 10 countries in hosting sporting events. But the enthusiasm and love has not deteriorated for the same rather it persists. India has been successful in conducting numerous national and international sports events. Sports comprise all the nerve wrecking matches which leave a don’t miss attitude to the audience watching the game. Let’s have a quick glance on some major international and domestic sporting events on Indian soil. Sports Events Hosted by India Domestic Sports The list of some major domestic sports events in India are as follows: 1. IPL • Indian Premier League is one of the major sports events of India. • Last 11 years IPL is being held every year in India. • This is the 12th edition of the lavish cricket league. 2. ISL • ISL or Indian Super League was introduced in 2013. • This football league has earned huge popularity as there is presence of famous domestic and international players. -

Live Services Powering Immersive, Addictive Viewing Proven Expertise Business Benefits

Managing The Business Of ContentTM Live Services Powering Immersive, Addictive Viewing Proven Expertise Business Benefits Experiences PFT’s industry first innovations for sports include: Faster time-to-market • A live to VoD ‘Zip Clip’ near real time feature to produce Live streaming allows fans across the globe to catch the action of Lower Total Cost of Operations (TCOP) and deliver VoD clips to sports consumers an event anywhere, anytime, on any device. PFT offers high quality • Getting DAI markers embedded in-stream to work in Realization of new monetization opportunities services for live streaming and VoD packaging with mid-roll and conjunction with Adobe Prime Time player, Ad Server, in-stream markers, for up to 28 concurrent live streams. Our Akamai and client engineering teams Premium streaming service allows insertion of promos, A History of Success • ‘Story Teller’ on Air – a specialized appliance that helps commercials, and branding elements during playout, enabling Indian Premier League (IPL): Live streaming and VoD packaging create compelling stories from MAM/archive for playout on customers to tap into new monetization opportunities. Our strong • Live streaming of 57 cricket matches for IPL 2010, the first air directly; with SDI ports for preview and output expertise in the sports genre, coupled with our armory of tools for sporting event ever to be streamed live on YouTube. • Developed the world’s first and only taxonomy for cricket, live multi-sport coverage, make us an ideal partner for Deliverables also included production set-up, live streaming with each ball being catalogued for over 120 parameters broadcasters, sports federations, OTT platforms, and brands alike. -

List of Indian Sports Achievements (2015-16) Archery Badminton Chess Cricket Cyclist Hockey

List of Indian Sports Achievements (2015-16) Team/ Person Result Event Venue Month Archery Deepika Kumari Won Silver Archery World Cup Mexico Oct'15 Abhishek Verma Won Silver Archery World Cup Mexico Oct'15 Badminton Women's Singles PV Sindhu Macau Open Macau Nov'15 Title World Junior Siril Verma Won Silver Lima Nov'15 Championship PV Sindhu Won Silver Denmark Open Denmark Oct'15 Ajay Jayaram Men’s Singles Title Dutch Open Netherland Oct'15 Malaysia Masters Grand PV Sindhu Won Title Malaysia Jan'16 Prix Chess 36th National Chess Indian Railways Won Title Bhubaneswar Feb'16 Championship FIDE Rating Chess Srishti Pandey Won Title Nagpur Nov'15 Tournament Cricket Multiple Venues Mumbai Won the Trophy Ranji Trophy Feb'16 in India India India won (2-1) T20I (Vs Sri Lanka) Andhra Pradesh Feb'16 India India won (3-0) T20I (Vs Australia) Australia Jan'16 India Won the Cup Blind T20 Asia Cup Kochi Jan'16 Cyclist Deborah Herold 4th Rank in World World Cyclist - Dec'15 Hockey Punjab Warriors Won the League Hockey India League Ranchi Feb'16 India Won Men's Title 8th Junior Asia Cup Malaysia Nov'15 Long Jump Mayookha Johny Won Gold Asian Indoor Athletics Doha Feb'16 Prem Kumar Won Silver Asian Indoor Athletics Doha Feb'16 Racing Jehan Daruvala Won Trophy Lady Wigram Trophy New Zealand Jan'16 Shooting Won 10m Air Rifle Apurvi Chandela Swedish Cup Grand Prix Sweden Jan'16 Event Won 10m Air Rifle 59th National Shooting Apurvi Chandela Delhi Dec'15 Event Championship Won 50m Air Rifle 59th National Shooting Chain Singh Delhi Dec'15 Event Championship -

Professional Sports Leagues Around the World and Sports Became a Business with Owners of Sports Teams on Lines Similar to Owners of Companies

EAMSA 2015 Competitive Paper 1. Introduction: Elite sports, the way we know it, have had a large fan following for more than a 100 years. The modern Olympics starting in 1896 was a turning point in organized elite sports across different types of sporting events. As the Olympics have evolved they have taken in more sports under its umbrella. Individual sports have had their own specialized events at regular intervals. These include the annual Wimbledon tennis tournament that started in 1877 and the Football World Cup held every four years that had its first edition in 1930. Initially elite sports people were amateurs for whom sports was a past time and not a profession. Over the years professionalization of sports took place as sports people converted what used to be a past time into a full-fledged profession. This led to the formation of a large number of professional sports leagues around the world and sports became a business with owners of sports teams on lines similar to owners of companies. Sports as a business opened up different ways to monetize the purchasing power of sports fans and led to the creation of a variety of different revenue models. The advent of professional sports leagues happened in Europe and North America. Europe developed professional sports leagues in football that included the English Premier League (EPL), La Liga in Spain, Bundesliga in Germany and Serie A in Italy. In North America the professional sports leagues revolved around the sports popular in that part of the world. These included Major League Baseball (MLB), National Basketball Association (NBA), National Football League (NFL), and National Hockey League (NHL). -

Coach Profiles Contents Domestic Coaches

Coach Profiles Contents Domestic Coaches HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 1. N Mukesh Kumar Nationality : India Page No. : 1 HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 2. Vasu Thapliyal HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE NaHOCKEYtionality INDIA LEA : GUEIndia HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE Page No. : 2-3 HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 3. Maharaj Krishon Kaushik Nationality : India Page No. : 4-5 HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 4. Sandeep Somesh Nationality : India HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE Page No. : 6 HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 5. Inderjit Singh Gill Nationality : India Page No. : 7-8 HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE Contents Domestic Coaches HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 6. Anil Aldrin Alexander Nationality : India Page No. : 9 HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE HOCKEY INDIA LEAGUE 7. -

Online Tickets Go Live for the Indian Hockey Team Home Matches of the FIH Hockey Pro League 2020 Today

Online Tickets go live for the Indian Hockey Team Home Matches of the FIH Hockey Pro League 2020 today ~ Tickets are available on ticketgenie.in from 1100hrs IST onwards ~ New Delhi, 21 November 2019: With close to two months to go for the second edition of the much-anticipated FIH Hockey Pro League 2020, Hockey India on Thursday announced that the sale of online tickets for the Indian home matches will go live today from 1100hrs IST onwards. It will be the first time that India will be participating in the FIH Hockey Pro League 2020, which will see the Indian Men's Hockey Team play hosts to the likes of The Netherlands, Belgium, Australia and New Zealand in a total of eight matches which will take place at the Kalinga Hockey Stadium in Bhubaneswar spanned from 18th January - 24 May 2020. The six-month long FIH Hockey Pro League 2020 will see World No. 5 Indian Men's Hockey Team start off their campaign by hosting World No. 3 The Netherlands in two home matches on 18th and 19th January 2020, which will be followed by the Indian team playing two more home matches against the World Champions, Belgium on 8th and 9th February 2020 at the Kalinga Hockey Stadium. India, who recently qualified for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games by defeating Russia in the FIH Hockey Olympic Qualifiers Odisha held in Bhubaneswar, will then be hosting World No. 1 Australia for two home matches on 21st and 22nd February 2020. These home matches will be followed by the Indian team touring World No. -

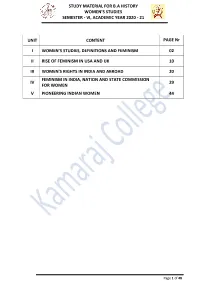

Women's Studies Has Moved Around the World As an Idea, a Concept, a Practice, and Finally a Field Or Fach (German for Specialty Or Field)

STUDY MATERIAL FOR B.A HISTORY WOMEN’S STUDIES SEMESTER - VI, ACADEMIC YEAR 2020 - 21 UNIT CONTENT PAGE Nr I WOMEN’S STUDIES, DEFINITIONS AND FEMINISM 02 II RISE OF FEMINISM IN USA AND UK 10 III WOMEN'S RIGHTS IN INDIA AND ABROAD 20 FEMINISM IN INDIA, NATION AND STATE COMMISSION IV 29 FOR WOMEN V PIONEERING INDIAN WOMEN 44 Page 1 of 48 STUDY MATERIAL FOR B.A HISTORY WOMEN’S STUDIES SEMESTER - VI, ACADEMIC YEAR 2020 - 21 UNIT - I WOMEN’S STUDIES, DEFINITIONS AND FEMINISM In its short history (from the late 1960s in the United States) women's studies has moved around the world as an idea, a concept, a practice, and finally a field or Fach (German for specialty or field). As late as 1982 in Germany Frauenstudium was not considered a Fach and therefore could not be studied in the university but only in special or summer courses. By the early twentieth century women's studies was recognized in higher education from India to Indonesia, from the United States to Uganda, China to Canada, Austria to Australia, England to Egypt, South Africa to South Korea, WOMEN'S STUDIES. In its short history (from the late 1960s in the United States) women's studies has moved around the world as an idea, a concept, a practice, and finally a field or Fach (German for specialty or field). As late as 1982 in Germany Frauenstudium was not considered a Fach and therefore could not be studied in the university but only in special or summer courses. -

Wrestling in Indian Literature

Wrestling in Indian Literature Kush Dhebar1 1. Pelican B flat 605, Raheja Woods, Kalyani Nagar, Pune -411006, Maharashtra, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 28 August 2016; Accepted: 03 October 2016; Revised: 18 October 2016 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 4 (2016): 251-260 Abstract: One can find stray reference to wrestling in Indian Literature, this article is an attempt to collate these references and create a rough time frame of wrestling right from ancient to modern period. Keywords: Wrestling, Physical Culture, History, Archaeology, Sports, Martial Arts, Literature Introduction Wrestling is the structured somatic principles based on how the wrestlers make sense of who they are through the medium of their bodies (Deshpande 1993: 202). The game of wrestling is considered the King of Manly games in India (Mujumdar 1950: 173). In Sanskrit it is known as Mallavidya and the people who practice it were known as Mallas (Joshi 1957: 51). Over a period of time the word wrestling became synonymous with a number of other words like Kushti, Malla-Yuddha, Bāhu-Yuddha, Pahalwani (Deshpande 1993: 202) and Saṅgraha (Agarwala 1953: 158). Wrestling takes place in akhādas or mallaśālas. Membership can range from 5-6 persons to 50-60 as well. All the members show their allegiance to a Guru who is aided by guru bhais or dadas in the management and the running of the akhādas. These akhādas usually have an earthen/mud pit where the wrestlers fight and practice, an exercise floor, a well and a temple or a shrine. Some exquisite akhādas also had vikśanamaṇḍapas (visitors’ galleries) where Mallakrīḍāmahotsavas (grand wrestling festivals) took place (Deshpande 1993: 202, Das 1985: 36, Joshi 1957: 51). -

FITNESS WEEK CELEBRATION” – Reg

CBSE/Dir (Trg. & SE)/2019 Date: November 06, 2019 Circular No.-ACAD-68/2019 All the Heads of the schools affiliated to CBSE SUBJECT: FIT INDIA MOVEMENT – “FITNESS WEEK CELEBRATION” – Reg. For any society or Nation to progress, it’s important that their citizens are physically fit. The challenges of the modern day life has brought along with it the need to be more physically proactive and fit in order to face its challenges with optimum energy and positivity. Fit children are able to handle day-to-day physical and emotional challenges better. However, for a holistic and intrinsically healthy lifestyle, awareness and support for fitness movement is more essential than ever. On 29 Aug 2019, the Honorable Prime Minister launched nation-wide “Fit India Movement” aimed to encourage people to inculcate physical activity and sports in their everyday lives and daily routine. So as to take this mission forward, CBSE has decided that each year SECOND and THIRD WEEK in November, a total of 06 working days, will be celebrated as “Fitness Week” in all its affiliated schools. This movement therefore endeavors to alter this behavior from ‘Passive Screen time’ to ‘Active Field time’ and the aim of the objective is to develop Sports Quotient among all the students to achieve a healthy lifestyle. Such movement will also instill in students the understanding for regular physical activity and higher levels of fitness enhancing in them self-esteem and confidence. It has also been decided to take-up “Ek Bharat – Shreshtha Bharat” on day six of this program. For this purpose, please see attached table as annexure “A”. -

Reading NFHS Data the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (Mohfw) Recently Released the Results from the First Phase of the National Family Health Survey (NHFS)

21st Dec 2020 CURRENT AFFAIRS Reading NFHS data The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) recently released the results from the first phase of the National Family Health Survey (NHFS). This is the fifth such survey and the first phase — for which data was collected in the second half of 2019 — covered 17 states and five Union Territories. The most important takeaway is that between 2015 and 2019, several Indian states have suffered a reversal on several child malnutrition parameters. In other words, instead of improving, several states have either seen child malnutrition increase or improve at a very slow rate. The second phase of the survey was disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic; its results are expected to come out in May 2021. The second phase will cover some of the biggest states such as Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab and Jharkhand. About NFHS NFHS is a large-scale nationwide survey of representative households. The data is collected over multiple rounds. The MoHFW has designated International Institute for Population Sciences in Mumbai as the nodal agency and the survey is a collaborative effort of IIPS; ORC Macro, Maryland (US); and the East-West Center, Hawaii (US). The survey is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) with supplementary support from UNICEF. This is the fifth NFHS and refers to the 2019-20 period. The first four referred to 1992-93, 1998-99, 2005-06 and 2015-16, respectively. The initial factsheet for NFHS-5 provides state-wise data on 131 parameters. These parameters include questions such as how many households get drinking water, electricity and improved sanitation; what is sex ratio at birth, what are infant and child mortality metrics, what is the status of maternal and child health, how many have high blood sugar or high blood pressure etc. -

Rise in Nregs Demand

(PRELIMS + MAINS FOCUS) SCO ONLINE INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION Venkaiah Naidu, Vice President of India & Chair of the SCO Council of Heads of Government in 2020, launched the first ever SCO Online Exhibition on Shared Buddhist Heritage, during the 19th Meeting of the SCO Council of Heads of Government (SCO CHG), held in New Delhi, in video-conference format. About: This SCO online International exhibition, first ever of its kind, is developed and curated by National Museum, New Delhi, in active collaboration with Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) member countries. The exhibition deploys state of the art technologies like 3D scanning, webGL platform, virtual space utilization, innovative curation and narration methodology etc. Buddhist philosophy and art of Central Asia connects Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) countries to each other. The visitors can explore the Indian Buddhist treasures from the Gandhara and Mathura Schools, Nalanda, Amaravati, Sarnath etc. in a 3D virtual format. PEACOCK SOFT-SHELLED TURTLE Recently, Peacock soft-shelled turtle (a turtle of a vulnerable species) has been rescued from a fish market in Assam’s Silchar. Key Points Scientific Name: Nilssonia hurum. Features: They have a large head, downturned snout with low and oval carapace of dark olive green to nearly black, sometimes with a yellow rim. The head and limbs are olive green; the forehead has dark reticulations and large yellow or orange patches or spots, especially behind the eyes and across the snout. Males possess relatively longer and thicker tails than females. Habitat: This species is confined to India, Bangladesh and Pakistan. In india, it is widespread in the northern and central parts of the Indian subcontinent. -

Tamil Cinema in the Twenty-First Century Caste, Gender, and Technology

Tamil Cinema in the Twenty-First Century Caste, Gender, and Technology Edited by Selvaraj Velayutham and Vijay Devadas First published 2021 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2021 selection and editorial matter, Selvaraj Velayutham and Vijay Devadas; individual chapters, the contributors The right of Selvaraj Velayutham and Vijay Devadas to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record has been requested for this book ISBN: 978-0-367-19901-2 (hbk) ISBN: 978-0-429-24402-5 (ebk) Typeset in Times New Roman by Deanta Global Publishing Services, Chennai,