Conflict Trends (No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emergency Plan of Action (Epoa) Niger: Complex Emergency

Page | 1 Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Niger: Complex Emergency Emergency MDRNE021 Glide n°: OT-2014-000126-NER Appeal / n° For Emergency 13 April Expected timeframe: 24 months (extended 12 months) Appeal: Date of 2018 launch: Expected end date: 30 April 2020 Category allocated to the of the disaster or crisis: Orange Emergency Appeal Funding Requirements: Revised to CHF 2,205,000 from CHF 1,680,731 DREF allocated: CHF 168,073 Total number of 461,323 Number of people to be 50,000 people revised from 43,113 people affected: assisted: if the total number of people people targeted is revised, Provinces Three Provinces/Regions targeted: One affected: Project manager: Pierre Danladi, overall responsible for planning, National Society contact: ISSA implementing, reporting and compliances. Mamane, Secretary General Host National Society presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): Diffa branch of the Niger Red Cross Society (NRCS) with 800 volunteers and eight staff Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Luxembourg Red Cross and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, WHO, OCHA, CARE, Save the Children, MSF Spain, OXFAM, World Vision, ACTED, UNFPA, DRC, Plan International, ACF, ONG KARKARA, APBE, ONG DIKO, Ministry of Humanitarian Action and Disaster Management, Ministry of Interior A. Situation analysis Description of the crisis The Diffa region of Niger continues to experience violence, inter-community conflicts, abduction and population movement as a result of armed groups activities. The current security situation remains extremely volatile and attacks by armed groups and military operations have kept people on the move, seeking safety and hoping for peace. -

Senegalese Grasshoppers: Localized Infestations in Niger from Northeastern Niamey Departement Over to Maradi Departement

Report Number 13 July 1987 FEWS Country Report NIGER Africa Bureau U.S. Agency for International Development YAP 1: NIGER Summary Map LIBYA ALGERI A Agadez Rainfall Deficit through 2nd decade As of MLy st oveal level of June Af0 st v,' of vegetation was above tL.attLae of 1986, and the average for 1982-66. As of June 20th, levels were st ll generally higher than // •. .. ... ..,.. -.. .. BEN I BENINNIGERIA Senegalese Grasshoppers: Localized infestations in Niger from northeastern Niamey Departement over to Maradi Departement. Very heavy infestations in Nigeria will likely move northward as rains advance into Niger. FEWSiPWA Famine Early Warning System Country Report NIGER The Rains Begin Prepared for the Africa Bureau of the U.S. Agency for International Development Prepared by Price, Williams & Associates, Inc. July 1987 Contents Page i Introduction 1 Summary 1 Meteorology 4 Vegetation Levels 9 Grasshoppers and Locusts List of Figures PaeC 2 Figure 1 Meteorology 3 Figure 2 Niger NVI Trends by Department 5 Figure 3 NVI Trends - Niamey Department 5 Figure 4 NVI Trends - Dosso Departmcnt 6 Figure 5 NVI Trends - Tahoua Department 7 Figure 6 NVI Trends - Maradi Department 7 Figure 7 NVI Trends - Zinder Department 8 Figure 8 NVI Trends - Diffa Department 9 Figure 9 NVI Trends - Agadez Department 10 Figure 10 Hatching Senegalese Grasshoppers Back Cover Map 2 Niger Reference Map INTRODUCTION This is the thirteenth in a series of monthly reports on Niger issued by the Famine Early Warning System (FEWS). It is designed to provide decisionmakers with current information and analysis on existing and potential nutrition emergency situations. -

Multi-Sectoral Support to Vulnerable Households in Diffa, Niger (Agreement No: 720FDA18GR00280)

Multi-sectoral support to vulnerable households in Diffa, Niger (Agreement No: 720FDA18GR00280) INTERNATIONAL RESCUE COMMITTEE NIGER SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT Multi-sectoral support to vulnerable households in Diffa, Niger AGREEMENT NO: 720FDA18GR00280 REPORTING PERIOD: AUGUST 1, 2018- MARCH 31, 2019 PRESENTED TO: THE USAID OFFICE OF FOREIGN DISASTER ASSISTANCE Collaborating Partner: Agency Headquarters: International Rescue Committee Niger International Rescue Committee c/o Giorgio Faedo, Country Director c/o Amelia Hays, Program Officer Tel: +227 92 18 74 01 Tel : 212.551.0954 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] SUBMITTED: MAY 1, 2019 Multi-sectoral support to vulnerable households in Diffa, Niger (Agreement No: 720FDA18GR00280) I. Executive Summary PROGRAM TITLE: Multi-sectoral support to vulnerable households in Diffa, Niger AGREEMENT: 720FDA18GR00280 AGENCY: International Rescue Committee in Niger CAUSE: WASH, protection, food security, shelter and NFI PROJECT PERIOD: 12 months (August 1, 2018 – July 31, 2019) OBJECTIVE: Improve the living conditions and build the resilience of vulnerable households in Diffa region, through emergency and early recovery interventions in the WASH, protection, food security, shelter, and NFI sectors BENEFICIARIES: Total number of beneficiaries targeted: 26,280 direct beneficiaries, including 14,580 IDPs Total number of beneficiaries reached to date: 15,359 beneficiaries, including 8,728 IDPs LOCATION: Region of Diffa, Niger WASH: Diffa, Maïné Soroa, and Goudoumaria departments Protection: N’Guigmi, Bosso, Diffa, Maïné Soroa, and Goudoumaria departments Agriculture and Food Security: N’Gourti, Diffa, Maïné Soroa, and Goudoumaria departments Shelter and Settlements: Diffa department 1 Multi-sectoral support to vulnerable households in Diffa, Niger (Agreement No: 720FDA18GR00280) I. -

Issue Paper No

Issue cov 139 2/12/06 4:02 PM Page 3 Issue paper no. 139 Land and water rights in the Sahel Tenure challenges of improving access to water for agriculture Edited by Lorenzo Cotula March 2006 Issue Paper 139 2/12/06 4:04 PM Page i Land and water rights in the Sahel Tenure challenges of improving access to water for agriculture Edited by Lorenzo Cotula Contributing authors Lorenzo Cotula, Ced Hesse, Oumar Sylla, Brigitte Thébaud, Gill Vogt and Kees Vogt Issue Paper no. 139 Issue Paper 139 2/12/06 4:04 PM Page ii About the authors This study was carried out by a multidisciplinary team of researchers. Lorenzo Cotula ([email protected]) is Research Associate – Law and Sustainable Development at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). His work focuses on the role of law (international, national and local/customary) in sustainable devel- opment – particularly in the areas of land/natural resource rights and tenure, international law on foreign investment, good governance and human rights. Ced Hesse is the Director of the Drylands Programme at the Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). Supporting the activities of pastoral civil society in their struggle to secure greater tenure security over land and other key natural resources is the main focus of his work in East Africa and the Sahel. Oumar Sylla is a member of the Association of Researchers on Legal Anthropology (Association des Chercheurs en Anthropologie Juridique – ACAJ), based in Paris. His work focuses on the link between decentralisa- tion policies and natural resource management in sub-Saharan Africa. -

Niger Food Security Update: February 25, 2001

Niger Food Security Update: February 25, 2001 Summary The food security situation in the arrondissement of Ouallam is troubling, especially in the cantons of Ouallam and Tondikiwindi. According to personnel of Afrique Verte (an international NGO working in the Department of Tillabéry), GTZ/ Projet Agro-Sylvo Pastorale (PASP) II (an integrated rural development project), and the Government of Niger agriculture service, the 2000 harvest was extremely poor. Farm household cereal stocks are depleted. The pasture situation is also very poor. There have been reports of unusually large migrations of able- bodied men as well as some entire families out of Ouallam in search of work and food. Due to limited coping strategies, many of the remaining people (mostly women and children) are surviving by gathering wild leaves and breaking into ant nests in search of grains to eat. Off- season gardening, which helps to offset the poor harvest, is practiced only in limited areas every year due to lack of sufficient water. Between January 28 and February 3, a joint mission of CILSS/PREGEC, FEWS NET, and RESAL was conducted in Niamey to assess the food security situation of the arrondissements identified as food insecure by the National Early Warning System (SAP) following the 2000/01 harvest. The mission recommended the free distribution of emergency food aid (for approximately 600,000 “severely food insecure” people within the arrondissements of Tchirozerine (Department of Agadez); Maine Soroa and N'Guigmi (Department of Diffa); and Filingue and Ouallam (Department of Tillabéry). This cereal food aid totals 38,535 MT based on a food ration of 20.25 kg/month/person for a period of three months during the peak of the hungry period, June-August. -

01-29-2016 Fact Sheet #4

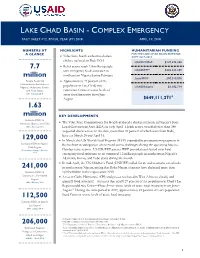

LAKE CHAD BASIN - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #4, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2016 JANUARY 29, 2016 NUMBERS AT A GLANCE HIGHLIGHTS HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE LAKE CHAD BASIN RESPONSE IN WFP reports 5.6 million FY 2015–FY 2016 2.5 food-insecure people in the region USAID/OFDA1 $30,287,761 USAID/FFP2 $77,629,741 million UN announces $31 million in People Displaced by Boko emergency funding to assist State/PRM3 $53,300,000 Haram-Related Insecurity vulnerable households in Lake Chad Basin USAID/Nigeria $33,800,000 OCHA – December 2015 Violence forces humanitarian actors to temporarily suspend response $195,017,502 5.6 interventions in Chad million People in Need of Emergency Food Assistance in the Region WFP – January 2016 KEY DEVELOPMENTS Attacks and raids by armed group Boko Haram continue to disrupt agricultural production and constrain economic activities throughout the Lake Chad Basin, affecting 2.2 Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria. The UN World Food Program (WFP) estimates that 5.6 million people in the region are in need of emergency food assistance—a 19 million percent increase in the food-insecure population since October 2015. IDPs in Nigeria Between December and January, the UN—in coordination with host country IOM – December 2015 governments—released the 2016 humanitarian response plans for Cameroon, Chad, and Nigeria. The plans, which target nearly 4.8 million people across the three countries for humanitarian assistance, require approximately $1.1 billion to implement critical food 58,926 security, health, protection, and shelter interventions. The funding requirement represents a 10 percent increase from the total amount requested in the countries’ 2015 IDPs in Niger OCHA – January 2016 plans, reflecting increased humanitarian needs across the region. -

Niger a Country Profile

REF 910,3 ? 54c'L/5" E92 NIGER ,Niger A Country Profile Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance Agency for International Development Washlngton, D.C. 20523 Niger LIS Y A ALGERIA International boundary Ddpartement bourdary * National capital Tamanrasset 0 DLpartement capital - Railroad Road 0 50 100 150 Kilometers a 50 100 1 Miles eBilma 1 -.. (( M ALI '\lm 9 5 5Ta)oua ae5 1 11 Go ur e' . :5 - . arni . Mha.... iarr7: BENINi~ / ( "-'er,IL" LChad ; ak-i-Tt rs UPPER ' Base 504113 11-79 (544513) NIGER: A COUNTRY PROFILE prepared for The Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance Agency for International Development Department of State Washington, D.C. 20523 by Mary M. Rubino Evaluation Technologies, Inc. c",C1 Arlington, Virginia under contract AID/SOD/PDC-C-3345 The country profile of Niger Is part of a series designed to provide baseline country data in support of the planning and relief operations of the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA). Content, scope, and sources have evolved over the course of the last several years and the relatively narrow focus is intentional. We hope that the information provided will also be useful to others in the disaster assistance and development communities. Every effort is made to obtain current, reliable data; unfortunately it Is not possible to issue updates as fast as changes would warrant. We invite your comments and corrections. Address these and other queries to OFDA, A.I.D., as given above. April 1985 OFDA COUNTRY PROFILES: APRIL 1985 AFRICA CARIBBEAN Burkina Faso CARICOM Regional Profile Cape Verde Antigua Chad Barbados East Africa Regional Profile Belize Djibouti Dominica Ethiopia Grenada Kenya Guyana Somalia Montserrat Sudan St. -

Rev. Ivoir. Sci. Technol., 36 (2020) 26 - 41 26 ISSN 1813-3290

Rev. Ivoir. Sci. Technol., 36 (2020) 26 - 41 26 ISSN 1813-3290, http://www.revist.ci ÉTUDE FLORISTIQUE DES DUNES FIXÉES À BASE DE LEPTADENIA PYROTECHNICA (FORSSK.) DECNE. DANS LA RÉGION DE DIFFA, NIGER 1 * 1 Abdoul Aziz ELHADJI SANOUSSI ISSOUFOU , Habou RABIOU , 2 1 Idrissa SOUMANA , Maman Kamal ABDOU HABOU 1,3 et Ali MAHAMANE 1 Université de Diffa, Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques, BP 78, Diffa, Niger 2 Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique du Niger, BP 429, Niamey, Niger 3 Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Laboratoire Garba Mounkaila, BP 10662, Niamey, Niger (reçu le 31 Octobre 2020 ; accepté le 1 Décembre 2020) _______________________ * Correspondance, e-mail : [email protected] RÉSUMÉ La présente étude a pour objectif, d’étudier la flore des dunes fixées à base de Leptadenia pyrotechnica. L’étude a été conduite dans deux départements de la région de Diffa. Le département de Diffa où les dunes fixées d’Issari ont été investiguées et le département de Maine soroa où les dunes fixées de Darsorom et Guel bayli ont été investiguées. Sur chacun des sites investigués, des placettes de 1000 m2 équidistantes de 100m suivant deux transects linéaires parallèles passant par le site ont été placées. Dans chaque placette, les coefficients d’abondance dominance de Braun blanquet ont été attribués à chacune des espèces présentes dans la placette. Les résultats montrent que les dunes fixées sont riches en espèces tant ligneuses qu’herbacées. La composition floristique montre que la famille de poaceae est la plus représentée sur les dunes fixées. L’analyse des types biologiques montre que les therophytes sont les types les plus représentés tant au niveau du spectre brute que pondéré. -

Lake Chad Basin Complex Emergency Fact Sheet

LAKE CHAD BASIN - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #12, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2018 APRIL 19, 2018 NUMBERS AT HIGHLIGHTS HUMANITARIAN FUNDING A GLANCE FOR THE LAKE CHAD BASIN RESPONSE • Yobe State health authorities declare IN FY 2017–2018 cholera outbreak in Bade LGA USAID/OFDA1 $147,694,288 7.7 • Relief actors reach 2.4 million people with emergency food assistance in USAID/FFP2 $405,224,249 northeastern Nigeria during February million State/PRM3 $90,010,000 People Requiring • Approximately 27 percent of the Humanitarian Assistance in population in Lac, Chad, may Nigeria’s Adamawa, Borno, USAID/Nigeria $6,182,734 and Yobe States experience Crisis or worse levels of UN – February 2018 acute food insecurity from June– 4 August $649,111,271 1.63 million KEY DEVELOPMENTS Estimated IDPs in • Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe The Yobe State Commissioner for Health declared a cholera outbreak in Nigeria’s Bade IOM – February 2018 Local Government Area (LGA) in early April. Health actors recorded more than 340 suspected cholera cases in the state, more than 95 percent of which were from Bade, between March 28 and April 16. 129,000 • In March, the UN World Food Program (WFP) expanded its pre-positioning capacity in Estimated IDPs in Niger’s Borno State in anticipation of increased access challenges during the upcoming May-to- Diffa Region Government of Niger – October October rainy season. USAID/FFP partner WFP provided cash-based or in-kind 2017 emergency food assistance to an estimated 1.2 million people in northeastern Nigeria’s Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe states during the month. -

NIGER Food Security Outlook October 2015 Through March 2016

NIGER Food Security Outlook October 2015 through March 2016 Continuing food insecurity in Diffa even after the end of the lean season KEY MESSAGES Current food security outcomes, October 2015 The average to above-average levels of cumulative rainfall in August-September helped compensate for the late start of the growing season, creating good soil water conditions for what is expected to be near-average crop and pasture production. However, there are localized areas with production deficits, particularly in Tera, Ouallam, Tanout, Abalak, Bermo, and Aderbissinat. There will be good water availability for irrigated crops grown between December 2015 and March 2016 from the heavy rains in August-September 2015. These irrigated crops, harvested between January and March 2015, will bolster household food availability and diversify household diets while, at the same time, boosting household income. Source: FEWS NET This map shows relevant current acute food insecurity outcomes Trends in market supplies and prices are in line with the norm, for emergency decision-making. It does not reflect chronic food insecurity. except on markets in conflict zones in the Diffa region. Barring any large local procurements, these favorable market conditions should extend into March 2016, with prices even liable to come down in December-January-February once all crops have been brought in. Driven by these generally positive factors, there will be Minimal (IPC Phase 1) acute food insecurity in most areas of the country between October 2015 and March 2016. However, conditions in certain pastoral areas of Abalak and Bermo and certain agropastoral areas of Téra, Ouallam, and Tanout will begin to be Stressed (IPC Phase 2) between February and March 2016. -

Displacement in Diffa Region Anticipated the Influx of up to 75,000 Newly Displaced from Bosso Department

ACAPS Briefing Note: Displacement in Niger Briefing Note – 09 June 2016 NIGER Key findings Displacement in Diffa region Anticipated The influx of up to 75,000 newly displaced from Bosso department scope and to spontaneous sites, refugee camps, and towns in Diffa and N’guigmi departments will further strain coping mechanisms and scale Need for international Not required Low Moderate Significant Major aggravate needs. Food insecurity is already at Crisis levels for assistance X many of the host communities and existing displaced, shelter and Very low Low Moderate Significant Major NFIs are lacking, and health and WASH facilities are overburdened. Expected impact X Operations will need to be scaled up dramatically in accessible areas. Crisis overview Priorities for Food and water for newly displaced arrivals. Boko Haram attacks in Yebi and Bosso, two towns in the east of Niger’s Diffa region, have humanitarian Shelter and NFIs, especially for those displaced who are living displaced an estimated 50,000–75,000 people since 19 May. Most of the displaced intervention in the open. population first sought safety in the town of Toumour, 25–30km west of Bosso town, but have since moved westwards and northwards, fearing further BH attacks. Protection for populations who face the threat of further BH Newly displaced populations are being reported among host communities and in attacks and military operations. spontaneous sites along the national highway that connects Diffa and N’guigmi departments. Others are heading to Kablewa, an official camp that is already nearing Humanitarian Access to Bosso department is not possible for humanitarian capacity. -

Appendix 1 Bhincidentsdec2017-Feb2019 Ver3

Appendix 1 . Wikipedia listing of terrorist incidents attributed to Boko Haram for the period Dec. 2017 - Feb. 2019 with corrections and additions by the author. Principal incidents (see Appendix 2) are indicated by color-filled cells in the Type column. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_terrorist_incidents_in_2017 (by month and also in 2018 and 2019). Principal Region Location Type WikiType Dead Injured/ Description and references to Wikipedia monthly Lists of Terrorist Incidents incidents Abducted 2017-12-02 B Suicide Fifteen persons were killed and 53 others injured in twin suicide bomb attacks in Biu 5 Biu, Borno 15 (+2) 53 (2f) bombings market in Borno.[7] 2017-12-10 Mc Ambush Quatre militaires ont été tués et 12 blessés dimanche lors d'une attaque de leur Nyeneri, nr convoy convoi, près de Damboa. Between Nyeneri et Falawani villages. https:// 5 Damboa, - 6+ 12 www.voaafrique.com/a/six-soldats-tues-dans-des-embuscades-tendues-par-boko-haram/ Borno 4159041.html “terrorists came in huge numbers and attacked the convoy using IEDs (improvised explosive devices) and gun trucks,”" 2017-12-11 Kerawa, B Suicide Two civilians and the bomber were killed when suicide bombing attacked a mosque after 4 FNR, (m) 2 (+1) 0 Bombing morning prayers in far northern Cameroon.[52] Cameroon 2017-12-13 Damboa, R 5 Shooting 5 0 Five people were killed by Boko Haram militants near Damboa .[61] Borno 2017-12-22/23 Kerawa- R Mafa, Three people were killed in two attacks in Zeneme and Kerawa-Mafa, Mayo Moskota 4 Shootings 3 0 FNR, region, in northern Cameroon by Boko Haram militants.[106] Cameroon 2017-12-28 Amarwa, B Suicide A suicide bombing caused by a Boko Haram militant at Amarwa, 20 km from Maiduguri, 5 Borno (m) 6 (+1) 13 Bombing in Borno State killed at least six people and injured 13 others.[131] State 2017-12-30 A Boko Haram fighters opened fire on a group of firewood cutters/collectors from Bakin Maiwa, Shooting, Muna in a remote village in northeast Nigeria, killing 25 people.