Tracing and Common Law Claims to Substitute Assets: Separating Myth from Reality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vocalink Blank

LINK Scheme Public - Redacted Copy Network Members Council Minutes of a Meeting of the Network Members Council Held at Cedar Court Hotel, Park Parade, Harrogate, HG1 5AH at 11.00 on Thursday 18th June 2015 Present: Dr Ken Andrew Independent Chairman Sarah Comley American Express Adrian Roberts Bank of Ireland Tim Allen Barclays Jonathan Simpson-Dent Cardtronics UK Craig Dye Co-operative Bank Lyndsay James Cumberland Building Society Bill Hoyne G4S Cash Solutions Glyn Warren HSBC Bank Mike Bullough Lloyds Bank Sue Bentley National Australia Group Anne Dalgleish Nationwide Building Society Kevin McMullan Northern Bank Nigel Constable NoteMachine Tim Watkin-Rees PayPoint Adam Bailey Royal Bank of Scotland Iain Gibson Sainsbury's Bank Helen Matthews Santander Anne Robertson Tesco Personal Finance Mark Akers TSB Bank Janice Aitken Yorkshire Building Society Jenny Campbell YourCash In Attendance: John Howells LINK Sue Wallace LINK Alex Leckenby LINK Graham Mott LINK Mary Buffee LINK Mandy Mahon LINK Deborah Thackwray LINK Sarah Chalmers LINK Katie Hinchley LINK Natalie Dix LINK Mike Newhouse LINK In Attendance for Item 7 only: Alistair Darling Giles Peel DAC Beachcroft LLP In Attendance for Item 9 only: Simon Walker KPMG Michelle Plevey KPMG 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Michael Coffey (AIB Group), Billy McCall (Airdrie Savings Bank), Paul Meehan (Change Group ATMs), Mick Willets (Citibank Savings), Neil Lover (Coventry Building Society), Gordon Rennison (Creation), Jean-Luc Dubois (Credit Mutuel), Tim Wilder (DC Payments UK), Nigel Emery (Metro Bank), Alan Chambers (Moneycorp), Beth Williams (Raphaels), Grant Wells (Travelex), and Dave Walker (Virgin Money). 18th June 2015 1 LINK Scheme Public - Redacted Copy Network Members Council The Independent Chairman welcomed to their first meeting of the NMC: Lyndsay James (Cumberland Building Society), Kevin McMullan (Northern Bank), and Mike Newhouse (LINK Scheme). -

PDF Print Version

HOUSE OF LORDS SESSION 2006–07 [2007] UKHL 34 on appeal from: [2005] EWCA Civ 389 OPINIONS OF THE LORDS OF APPEAL FOR JUDGMENT IN THE CAUSE Sempra Metals Limited (formerly Metallgesellschaft Limited) (Respondents) v. Her Majesty’s Commissioners of Inland Revenue and another (Appellants) Appellate Committee Lord Hope of Craighead Lord Nicholls of Birkenhead Lord Scott of Foscote Lord Walker of Gestingthorpe Lord Mance Counsel Appellants: Respondents: Ian Glick QC Laurence Rabinowitz QC Rupert Baldry Francis Fitzpatrick Gerry Facenna Steven Elliott (Instructed by Solicitor’s Office, HM Revenue and (Instructed by Slaughter & May) Customs ) Hearing dates: 1 and 2 November 2006 Further heard: 16 May 2007 ON WEDNESDAY 18 JULY 2007 HOUSE OF LORDS OPINIONS OF THE LORDS OF APPEAL FOR JUDGMENT IN THE CAUSE Sempra Metals Limited (formerly Metallgesellschaft Limited) (Respondents) v. Her Majesty’s Commissioners of Inland Revenue and another (Appellants) [2007] UKHL 34 LORD HOPE OF CRAIGHEAD My Lords, 1. This is a case about the award of interest. Questions about interest usually arise where the claim is presented as ancillary to a claim for a principal sum for which the court is asked to give judgment for the recovery of a debt or as damages. Less usually they can arise where interest is sought on a principal sum which has been paid before judgment. But in this case interest is the measure of the principal sum itself. 2. The question is how that sum should be measured. It is agreed that the calculation of interest should be the method of measurement for the sum that is to be awarded. -

Simplified Access to the UK's Payments Systems Takes Another

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release 15 December 2016 Simplified access to the UK’s payments systems takes another step forward with the publication of a new, cross-scheme guide to participation The UK’s interbank Payments System Operators (PSOs) – Bacs Payment Schemes Limited (Bacs), CHAPS, Cheque and Credit Clearing Company, Faster Payments and LINK – have today published a new guide entitled, An Introduction to the UK’s Interbank Payment Schemes. Available on each of the PSOs’ websites, the guide is intended for use by payments service providers (PSPs) that are considering joining, or thinking of extending more payments services to their customers. The document provides an overview of the UK’s payment schemes, what each one offers, and how they can be accessed by PSPs. It has been developed collaboratively by the schemes, capturing input from the Payments Strategy Forum, a number of challenger banks and FinTechs. This is another important step forward in the journey to open up the UK’s payments systems. This year has already seen broadening access to the schemes, with Raphaels and Metro Bank joining Faster Payments, and Societe Generale and Northern Trust joining CHAPS. In 2017, the interbank schemes are expecting growth in direct participation to continue to accelerate. Hannah Nixon, Managing Director of the Payment Systems Regulator, said: “Simple, clear and fair requirements will help make it easier to gain access to the UK’s Interbank Payment Systems. As the economic regulator for the £75 trillion UK payment systems industry, we welcome the work that has been undertaken to produce this guide – which should help introduce organisations to the different access options available to them in each of the payment systems. -

The Ritz London, 16Th November 2016 by Invitation Only Confidential – Not for Distribution

® The Ritz London, 16th November 2016 By Invitation Only The AI Finance Summit is the world’s first and only high-level conference exploring the impact of Artificial Intelligence on the financial services industry. The invitation-only event, brings together CxOs from the world’s leading banks, insurance companies, asset management organisations, brokers. The event takes place at London’s most prestigious address, The Ritz, on the 16th of November and features world-class speakers presenting exclusive case studies shedding light into how the 4th industrial revolution will affect specifically affect the financial services industry. DRAFT AGENDA 16tH November 2016, The Ritz London 08:30 Registration, Breakfast refreshments & Networking 09:15 A welcome unlike any other… and Chair’s Opening Remarks 09:20 State of Play opening keynote: the 4th industrial revolution in financial services Where are financial services currently at with artificial intelligence, what technologies in particular are being used, how quickly is it being adopted, and what areas are leading the adoption of new intelligent technologies? These are are some of the pivotal questions answered in the scene-setting opening keynote to the AI Finance Summit. 09:45 Introducing a new era of risk management in investment banking The use of artificial intelligence within the world of investment banking is a phenomenon which is going to propel the industry in more ways than one. This talk will discuss how the advent of AI technologies, focusing on machine learning and cognitive computing, will drastically enhance risk management processes and achieve levels of accuracy previously unseen in the industry 10:10 Customer Experience/ Relations Management through AI platforms AI is revolutionizing customer service across every industry, with financial services already a pioneer in adoption. -

Beyond Unconscionability: the Case for Using "Knowing Assent" As the Basis for Analyzing Unbargained-For Terms in Standard Form Contracts

Beyond Unconscionability: The Case for Using "Knowing Assent" as the Basis for Analyzing Unbargained-for Terms in Standard Form Contracts Edith R. Warkentinet I. INTRODUCTION People who sign standard form contracts' rarely read them.2 Coun- sel for one party (or one industry) generally prepare standard form con- tracts for repetitive use in consecutive transactions.3 The party who has t Professor of Law, Western State University College of Law, Fullerton, California. The author thanks Western State for its generous research support, Western State colleague Professor Phil Merkel for his willingness to read this on two different occasions and his terrifically helpful com- ments, Whittier Law School Professor Patricia Leary for her insightful comments, and Professor Andrea Funk for help with early drafts. 1. Friedrich Kessler, in a pioneering work on contracts of adhesion, described the origins of standard form contracts: "The development of large scale enterprise with its mass production and mass distribution made a new type of contract inevitable-the standardized mass contract. A stan- dardized contract, once its contents have been formulated by a business firm, is used in every bar- gain dealing with the same product or service .... " Friedrich Kessler, Contracts of Adhesion- Some Thoughts About Freedom of Contract, 43 COLUM. L. REV. 628, 631-32 (1943). 2. Professor Woodward offers an excellent explanation: Real assent to any given term in a form contract, including a merger clause, depends on how "rational" it is for the non-drafter (consumer and non-consumer alike) to attempt to understand what is in the form. This, in turn, is primarily a function of two observable facts: (1) the complexity and obscurity of the term in question and (2) the size of the un- derlying transaction. -

Tracing Is a Process Not a Remedy

Tracing - Scenario 1(b): Trustee Mixes Trust Money - Tracing is a process not a remedy. With His Own In His Account, subsequently - It allows us to identify a new asset as the purchases property with some money in the substitute for the old (Foskett v McKeown). account, then exhausts remaining money. - Tracing follows the value of the beneficiaries - SOLUTION: Re Oatway: We get an property, not the property itself (following). exception to the rule in Hallett’s estate: if the wrongdoer purchased assets which still exist, Distinguishing Tracing; Following & Claiming then it is presumed that he did so with the - Following is the process of following the same stolen money and the beneficiaries are asset as it moves from hand to hand. entitled to the assets. - Claiming refers to the process of recovering property, or the substitute for that property (This - Scenario 1(c): Trustee Mixes Money With His refers to the Barnes v Addy; knowing receipt, Own In His Account, and makes payment in knowing assistance doctrine - MUST and out of that account. CONSIDER THIS AFTER TRACING). - SOLUTION: Lofts v McDonald: Lowest Intermediate Balance Rule: trust cannot claim more than the lowest intermediate balance Tracing at Common Law - credited to the wrongdoer’s bank account Tracing is not unique to equity, however at CL it - If it went up from the lowest point, that is requires that the property you are tracing is not the trust’s money. identifiable, giving rise to problems with banks. - - Although you are deprived of a proprietary Equity has developed rules for identifying remedy, not personal remedies. -

C00 Br Eq&Tr Prelims.Ps

衡平法和信托法简明案例s Briefcase on Equity and Trust Third Edition Gary Watt , MA ( Oxon), Solicitor 武 汉 大 学 出 版 社 本 书 导 读 信托制度起源于中世纪英国的 衡平 法 , 因为 当时英 国普 通法院 不承 认 受益人依赖于受托人获得的权利 , 而衡 平法 院则 总是通 过对 受托人 施加 衡 平法上的义务来支持这种权利的。 它是 英美 法系一 个独 特的制 度 , 在大 陆 法系中几乎找不到一个与之相对应的制度。又由于信托制度是建立在双重 所有权观念基础之上的 , 即受托 人享有 普通 法上 的所有 权而 受益人 享有 衡 平法上的所有权 , 所以坚持一物 一权主 义的 大陆 法国家 在接 受和移 植该 制 度的时候难免与英美法中该制度有所差异。对于学习信托法的人来说有必 要参考一下英美法学者有关信 托法的 论著。 本书就 是这 样一 本案例 教材 , 作者在理论和实务的基础上运用各 种案 例讲 述了信 托法 的基本 制度 , 这 对 于我们这些长期接受大陆法系理论教育的人来说的确是一种很新颖的教学 方式。 本书既介绍了衡平法与信托法 的历 史沿 革 , 也介绍 了它 们最近 的一 些 最新发展。全书分为六个部分 , 第一部分主要是介绍衡平法和信托法 ; 第二 部分则叙述了明示信托的设立 , 该部分又分了 8 节 , 逐一介绍了设立明示信 托行为能力与要式的要求 , 确定 性的 要求 , 赠 与的完 成与 信托的 设立 , 永 久 权与信托设立时的公共政策限制 , 目 的信托 , 公益信 托和 特殊种 类信 托 ; 第 三部分探讨了明示信托变更 的各 种方 式以及 1958 年信 托变 更法中 对于 变 更的要求 ; 第四部分则分析了受托人的地位和职责 , 同时也分析了类似于受 托人的人的地位和义务 , 该部分 又分 6 节 , 逐 一介绍 了受 托人 的职的 任命 , 受托人的职的履行 , 受托人的义 务 , 受托 人投 资的权 利及 义务 , 抚养 与预 付 以及信托违约的抗辩与免除 ; 第 五部分 则把 重点 放在拟 制信 托与回 归信 托 之上 , 讲解了推定的回归信托 , 自动的回归信托 , 地产的拟制信托 , 拟制信托 受托人的义务 , 陌生人作为拟制信托的受托人等许多内容 ; 最后作者谈到了 追及与衡平法上的救济 , 在讲到追及的时候既谈到了普通法上的追及 , 又谈 到了衡平法上的追击 , 在讲衡平 法上的 救济 的时 候则讲 到了 衡平法 上对 于 实际履行的救济和衡平法上的禁令。 本书作 为介 绍 英国 信托 法律 制度 的 基本 读物 , 内容 简明 扼要 , 通俗 易 懂。作者理论联系实际 , 借助丰富翔实的案例 , 深入浅出地勾勒出了英国信 托法的基本框架制度。这对于我们 开展 比较 研究 , 理解 和掌 握英国 美法 系 1 相关法律知识 , 借鉴和学习英美法系相对成熟的法律制度是大有裨益的。 本书中文目录、法规一览表、术语及索引部分由武汉大学民商法博士研 究生王茂祺翻译并整理 , 纰漏之处在所难免 , 希望广大读者多提宝贵意见。 译 者 2004 年 4 月 2 Glos sar y 术 语 Abbot t Fund, Re: Two old ladies 两个老年妇女 � Abergavenny’s ( Marquess of) , Re : Advancement used up 预付已用完 Abrahams, Re: 25 year old infant ? 25 岁的婴儿 ? Abrahams v Trustee in Bankruptcy -

(A) Panag. Prelims

RESTITUTION IN PRIVATE INTERNATIONAL LAW Restitution in Private International Law GEORGE PANAGOPOULOS B. A., LL.B (hons.) (Mon.) B.C.L., D.Phil. (Oxon) Barrister and Solicitor of Victoria, Australia Solicitor, England and Wales OXFORD – PORTLAND OREGON 2000 Hart Publishing Oxford and Portland, Oregon Published in North America (US and Canada) by Hart Publishing c/o International Specialized Book Services 5804 NE Hassalo Street Portland, Oregon 97213-3644 USA Distributed in the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg by Intersentia, Churchillaan 108 B2900 Schoten Antwerpen Belgium © George Panagopoulos 2000 The author has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work Hart Publishing Ltd is a specialist legal publisher based in Oxford, England. To order further copies of this book or to request a list of other publications please write to: Hart Publishing Ltd, Salter’s Boatyard, Oxford OX1 4LB Telephone: +44 (0)1865 245533 or Fax: +44 (0)1865 794882 e-mail: [email protected] www.hartpub.co.uk British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data Available ISBN 1 84113–142–3 (cloth) Typeset by Hope Services (Abingdon) Ltd. Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Biddles Ltd, Guildford and King’s Lynn. “λλ πειρ ται τ ζημ α σζειν, φαιρν τ κρδο . στε τ πανορθωτικν δκαιον "ν ε#η τ μσον ζημα κα$ κρδου” &Αριστοτλη, &Ηθικ Νικομχεια, V 4 1132α 9–10, 18–19 “but (the judge) tries to equalize things by the penalty he imposes, taking away the gain . therefore the restitutionary justice is the mean between loss and gain” Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics V 4 1132a 9–10, 18–19 Preface This book is based on my doctoral thesis, which was submitted at the University of Oxford in July 1999. -

Asset Tracing in the British Virgin Islands

Article Asset Tracing in the British Virgin Islands In this article, we will discuss some of the tools available to a party in the British Virgin Islands to seek to recover property, or proceeds of property, which have been misappropriated. It is not surprising that in some cases, the identity of the wrongdoer or the whereabouts of the misappropriated property is unknown. Against that background, it is worth noting that while a BVI, and whether there has been any past judgment which company incorporated in the BVI is required to maintain may shed light on assets held by the company. In addition, certain records at the office of its registered agent (such as upon application the BVI Land Registry can provide certain its memorandum and articles of association, register of details regarding the owner of BVI land or real estate. directors, register of members, minutes of members’ and However, this requires the applicant to first be able to directors’ meetings and copies of resolutions), there is no identify the location or owner of the land. A party may also right for the public to inspect such records. Indeed, obtain certain information regarding vessels registered under confidentiality of corporate documents and information is a BVI flag from the BVI Ship Registry. one of the key attractions of incorporating a company in the BVI. BVI companies are not generally required to maintain or What is “tracing”? file statutory accounts, or meet any particular set of international accounting standards. Under section 98 of the Tracing consists of a series of rules developed by equity to BVI Business Companies Act 2004, all that a company is deal with situations where assets have been required to maintain are records “sufficient to show and misappropriated and the wrongdoer is not in a position to explain the company’s transactions” and which “will, at any compensate, or money compensation is not adequate. -

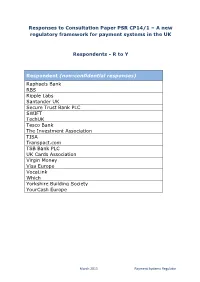

Responses to Consultation Paper PSR CP14/1 – a New Regulatory Framework for Payment Systems in the UK

Responses to Consultation Paper PSR CP14/1 – A new regulatory framework for payment systems in the UK Respondents - R to Y Respondent (non-confidential responses) Raphaels Bank RBS Ripple Labs Santander UK Secure Trust Bank PLC SWIFT TechUK Tesco Bank The Investment Association TISA Transpact.com TSB Bank PLC UK Cards Association Virgin Money Visa Europe VocaLink Which Yorkshire Building Society YourCash Europe March 2015 Payment Systems Regulator RAPHAELS BANK RAPHAELS BANK RAPHAELS BANK Page 2 of 10 Question in relation to our proposed regulatory approach (see Part B of our Consultation Paper and Supporting Paper 1: The PSR and UK payments industry for more details) SP1-Q1: Do you agree with our regulatory approach? If you disagree with our proposed approach, please give your reasons. We broadly support your approach but we are concerned that regulation needs to be joined up between yourselves, the PRA, FCA, CMA and BoE. We have heard and read that this will be the case, however, we have seen major disruption through withdrawal of banking support in the market for payments providers in the past two years which appears to be continuing without any apparent regulatory intervention. You have rightly identified access to payment systems as an important area for your involvement, however, if indirect access is to work, there has to be a range of sponsoring banks providing such services. This market is limited and apparently contracting, exacerbated by the closure and non-availability of bank accounts from clearing banks to the sector. Some sponsoring banks have made significant moves to close bank accounts on policy grounds to UK payments providers and this is continuing today partly, we believe, in response to increased regulation. -

STRANGER LIABILITY: a QUESTION of CONSCIENCE PROPERTY OR STANDARDS? by Kerrell Ma* PART ONE Introduction Trustees Have Some Onerous Duties

STRANGER LIABILITY: A QUESTION OF CONSCIENCE PROPERTY OR STANDARDS? by Kerrell Ma* PART ONE Introduction Trustees have some onerous duties. Their principle duty is to discharge themselves by accounting to their beneficiaries for the trust property. That duty or a duty akin to it should not be imposed lightly on any persons other than an express trustee, unless those persons' actions in relation to the trust property are such that they ought to attract such a duty. Furthermore, before equity imposes a liability on persons other than an express trustee (referred to as strangers to the trust) for participating in a breach of trust or breach of fiduciary duty there should be a clear reason for so doing. Is it because of: 1.the unconscionable behaviour of the stranger in relation to the property; or 2. the stranger's fault in not realising that the dealing with the property constitutes a breach of trust or fiduciary duty or that any assistance rendered enables a breach to be committed; or 3. the stranger's notice in respect of the breach; or 4. the stranger's unjust enrichment by receipt of property, or for more than one of these reasons? Judges and academics cannot agree on the underlying basis for the obligations imposed on strangers for receipt of property received in breach of trust or in breach of fiduciary duties or for the rendering of assistance in such breaches.1 It is then no small wonder that with the offering of different paths, the law in relation to constructive trust liability for strangers to trusts is in disarray. -

Administration of Trusts

Administration of Trusts Administration of Trusts Denis Barlin Barrister 13 Wentworth Selborne Chambers 174-180 Phillip Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 (02) 9231 6646 [email protected] page 1 Administration of Trusts Contents 1 General principles – trusts ................................................................................. 4 1.1 Trustee’ Duties .................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Duty to carry out terms of the trust .................................................................................. 5 1.3 Duty of care in the management of the trust affairs ........................................................ 5 1.4 Duty to act impartially ....................................................................................................... 7 1.5 Duty to perform trusts honestly and in good faith for the benefit of beneficiaries ......... 7 1.6 Bankruptcy Act considerations.......................................................................................... 8 1.7 Undervalue transfers ......................................................................................................... 8 1.8 Transfers to defeat creditors ........................................................................................... 10 2 The Court’s power to remove a trustee ............................................................ 12 3 Statutory power of appointment ..................................................................... 16 4 The