Digital Musical Instruments As Probes: How Computation Changes the Mode-Of-Being of Musical Instruments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Bernhard Gander, Ensemble Modern, Attila Csihar, Kevin Paradis Oren

Bernhard Gander, Ensemble Modern, Attila Csihar, Kevin Paradis 20OOZING EARTH Oren Ambarchi, Attila Csihar, Stephen O’Malley GRAVETEMPLE 20 MUSIK Ort Halle E im MuseumsQuartier Warm up! Einführungen, Lectures und Gespräche 13. September, 18.30 Uhr, Crossing over: Neue Termin 13. September, 20 Uhr Musik meets Metal, Gespräch mit Bernhard Gander Dauer 2 Std. 30 Min., inkl. 1 Umbaupause und Attila Csihar, in englischer Sprache, Portikus im Haupthof des MuseumsQuartier Wir bitten Sie, während dieser kurzen Pause den Saal nicht zu verlassen. Der erste Engel blies seine Posaune. Da fielen Hagel und Feuer, die mit Blut vermischt waren, auf das Land. Es verbrannte ein Drittel des Landes, ein Drittel der Bäume und alles grüne Gras. OFFENBARUNG 8,7 The first angel sounded, and there followed hail and fire mingled with blood, and they were cast upon the Earth: and the Mit Musik von Bernhard Gander, Oozing Earth, for voice, extreme-metal drummer and ensemble third part of trees was burnt up, Interpretiert von Attila Csihar / Stimme, Kevin Paradis / Schlagzeug, Ensemble Modern (Dietmar Wiesner / Flöte, Christian Hommel / Oboe, Hugo Queirós / Klarinette, Johannes Schwarz / Fagott, Saar Berger / and all green grass was burnt up. Horn, Sava Stoianov / Trompete, Mikael Rudolfsson / Posaune, Ueli Wiget / Klavier, Hermann Kretzschmar / Klavier, David Haller / Perkussion, Rainer Römer / Perkussion, Jagdish Mistry / Violine, Giorgos Panagiotidis / Violine, Megumi Kasakawa / Viola, Paul Beckett / Viola, Eva Böcker / Violoncello, REVELATION 8:7 Michael Maria Kasper / Violoncello, Paul Cannon / Kontrabass, Norbert Ommer / Klangregie) Dirigent Bas Wiegers Und Musik von Gravetemple (Attila Csihar, Oren Ambarchi, Stephen O’Malley) Lichtkonzept Raphael Haider, Marlene Posch durchgeführt vom Team Wiener Festwochen Uraufführung Oozing Earth, März 2020, cresc… Biennale für aktuelle Musik Frankfurt Rhein Main 2 DE / EN 3 DER ULTIMATIVE ABGESANG AUF DIE MENSCHHEIT unfreiwilligen Propheten. -

Mysticism, Implicit Religion and Gravetemple's Drone Metal By

1 The Invocation at Tilburg: Mysticism, Implicit Religion and Gravetemple’s Drone Metal by Owen Coggins 1.1 On 18th April 2013, an extremely slow, loud and noisy “drone metal” band Gravetemple perform at the Roadburn heavy metal and psychedelic rock festival in Tilburg in the Netherlands. After forty-five minutes of gradually intensifying, largely improvised droning noise, the band reach the end of their set. Guitarist Stephen O’Malley conjures distorted chords, controlled by a bank of effects pedals; vocalist Attila Csihar, famous for his time as singer for notorious and controversial black metal band Mayhem, ritualistically intones invented syllables that echo monastic chants; experimental musician Oren Ambarchi extracts strange sounds from his own looped guitar before moving to a drumkit to propel a scattered, urgent rhythm. Momentum overtaking him, a drumstick slips from Ambarchi’s hand, he breaks free of the drum kit, grabs for a beater, turns, and smashes the gong at the centre of the stage. For two long seconds the all-encompassing rumble that has amassed throughout the performance drones on with a kind of relentless inertia, still without a sonic acknowledgement of the visual climax. Finally, the pulsating wave from the heavily amplified gong reverberates through the corporate body of the audience, felt in physical vibration more than heard as sound. The musicians leave the stage, their abandoned instruments still expelling squalling sounds which gradually begin to dissipate. Listeners breathe out, perhaps open their eyes, raise their heads, shift their feet and awaken enough to clap and shout appreciation, before turning to friends or strangers, reaching for phrases and gestures, often in a vocabulary of ritual, mysticism and transcendence, which might become touchstones for recollection and communication of their individual and shared experience. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

d o n e i t . MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS R Tit e l der M a s t erarbei t / Titl e of the Ma s t er‘ s Thes i s e „What Never Was": a Lis t eni ng to th e Genesis of B lack Met al d M o v erf a ss t v on / s ubm itted by r Florian Walch, B A e : anges t rebt e r a k adem is c her Grad / i n par ti al f ul fi l men t o f t he requ i re men t s for the deg ree of I Ma s ter o f Art s ( MA ) n t e Wien , 2016 / V i enna 2016 r v i Studien k enn z ahl l t. Studienbla t t / A 066 836 e deg r ee p rogramm e c ode as i t appea r s o n t he st ude nt r eco rd s hee t: w Studien r i c h tu ng l t. Studienbla tt / Mas t er s t udi um Mu s i k w is s ens c ha ft U G 2002 : deg r ee p r o g r amme as i t appea r s o n t he s tud e nt r eco r d s h eet : B et r eut v on / S uper v i s or: U ni v .-Pr o f. Dr . Mi c hele C a l ella F e n t i z |l 2 3 4 Table of Contents 1. -

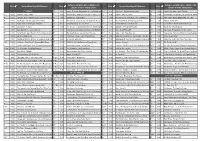

Price Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price Follow Us on Twitter

Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ updates on items selling out etc. updates on items selling out etc. 7" SINGLES 7" 14.99 Queen : Bohemian Rhapsody/I'm In Love With My Car 12" 22.99 John Grant : Remixes Are Also Magic 12" 9.99 Lonnie Liston Smith : Space Princess 7" 12.99 Anderson .Paak : Bubblin' 7" 13.99 Sharon Ridley : Where Did You Learn To Make Love The 12" Way You 11.99Do Hipnotic : Are You Lonely? 12" 10.99 Soul Mekanik : Go Upstairs/Echo Beach (feat. Isabelle Antena) 7" 16.99 Azymuth : Demos 1973-75: Castelo (Version 1)/Juntos Mais 7" Uma Vez9.99 Saint Etienne : Saturday Boy 12" 9.99 Honeyblood : The Third Degree/She's A Nightmare 12" 11.99 Spirit : Spirit - Original Mix/Zaf & Phil Asher Edit 7" 10.99 Bad Religion : My Sanity/Chaos From Within 7" 12.99 Shit Girlfriend : Dress Like Cher/Socks On The Beach 12" 13.99 Hot 8 Brass Band : Working Together E.P. 12" 9.99 Stalawa : In East Africa 7" 9.99 Erykah Badu & Jame Poyser : Tempted 7" 10.99 Smiles/Astronauts, etc : Just A Star 12" 9.99 Freddie Hubbard : Little Sunflower 12" 10.99 Joe Strummer : The Rockfield Studio Tracks 7" 6.99 Julien Baker : Red Door 7" 15.99 The Specials : 10 Commandments/You're Wondering Now 12" 15.99 iDKHOW : 1981 Extended Play EP 12" 19.99 Suicide : Dream Baby Dream 7" 6.99 Bang Bang Romeo : Cemetry/Creep 7" 10.99 Vivian Stanshall & Gargantuan Chums (John Entwistle & Keith12" Moon)14.99 : SuspicionIdles : Meat EP/Meta EP 10" 13.99 Supergrass : Pumping On Your Stereo/Mary 7" 12.99 Darrell Banks : Open The Door To Your Heart (Vocal & Instrumental) 7" 8.99 The Straight Arrows : Another Day In The City 10" 15.99 Japan : Life In Tokyo/Quiet Life 12" 17.99 Swervedriver : Reflections/Think I'm Gonna Feel Better 7" 8.99 Big Stick : Drag Racing 7" 10.99 Tindersticks : Willow (Feat. -

Order Form Full

METAL ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 1349 MASSIVE CAULDRON OF CHAOS (SPLATTER SEASON OF MIST RM121.00 16 LIFESPAN OF A MOTH RELAPSE RM111.00 16 LOST TRACTS OF TIME (COLOR) LAST HURRAH RM110.00 3 INCHES OF BLOOD BATTLECRY UNDER A WINTERSUN WAR ON MUSIC RM102.00 3 INCHES OF BLOOD HERE WAITS THY DOOM WAR ON MUSIC RM113.00 ACID WITCH MIDNIGHT MOVIES HELLS HEADBANGER RM110.00 ACROSS TUNDRAS DARK SONGS OF THE PRAIRIE KREATION RM96.00 ACT OF DEFIANCE BIRTH & THE BURIAL (180 GR) METAL BLADE RM147.00 ADMIRAL SIR CLOUDESLEY SHOVELL KEEP IT GREASY! (180 GR) RISE ABOVE RM149.00 ADMIRAL SIR CLOUDSLEY SHOVELL CHECK 'EM BEFORE YOU WRECK 'EM RISE ABOVE RM149.00 AGORAPHOBIC NOSEBLEED FROZEN CORPSE STUFFED WITH DOPE RELAPSE RECORDS RM111.00 AILS THE UNRAVELING FLENSER RM112.00 AIRBOURNE BLACK DOG BARKING ROADRUNNER RM182.00 ALDEBARAN FROM FORGOTTEN TOMBS KREATION RM101.00 ALL OUT WAR FOR THOSE WHO WERE CRUCIFIED VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 ALL PIGS MUST DIE NOTHING VIOLATES THIS NATURE SOUTHERN LORD RM101.00 ALL THAT REMAINS MADNESS RAZOR & TIE RM138.00 ALTAR EGO ART COSMIC KEY CREATIONS RM119.00 ALTAR YOUTH AGAINST CHRIST COSMIC KEY CREATIONS RM123.00 AMEBIX MONOLITH (180 GR) BACK ON BLACK RM141.00 AMEBIX SONIC MASS EASY ACTION RM129.00 AMENRA ALIVE CONSOULING SOUND RM139.00 AMENRA MASS I CONSOULING SOUND RM122.00 AMENRA MASS II CONSOULING SOUND RM122.00 AMERICAN HERITAGE SEDENTARY (180 GR CLEAR) GRANITE HOUSE RM98.00 AMORT WINTER TALES KREATION RM101.00 ANAAL NATHRAKH IN THE CONSTELLATION OF THE.. (PIC) BLACK SLEEVES RM128.00 ANCIENT VVISDOM SACRIFICIAL MAGIC -

Punk Section

A “nihilistic dreamboat to negation”? The cultural study of death metal and the limits of political criticism Michelle Phillipov Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Discipline of English University of Adelaide October 2008 CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................... II Abstract.................................................................................................................... IV Declaration ........................................................................................................ VI Acknowledgements ............................................................................. VII Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 From heavy to extreme metal ............................................................................................. 9 The politics of cultural studies .......................................................................................... 20 Towards an understanding of musical pleasure ............................................................. 34 Chapter 1 Popular music studies and the search for the “new punk”: punk, hip hop and dance music ........................................................................ 38 Punk studies and the persistence of politics ................................................................... 39 The “new punk”: rap and hip hop .................................................................................. -

Drunk Detective Starkness

Vol. 11 june 2019 — issue 6 iNSIDE: DRUNK DETECTIVE STARKNESS - STILL DRINKING HIJACKED - LOUDFEST REDUX - SALACIOUS VEGAN CRUMBS - OF BUTTERFLIES, RAINBOWS & UNICORNS - game of life - SHIT IM SUPPOSED TO LIKE BUT DONT - good movies for bad guys - ANARCHY FROM THE GROUND UP - HAIL SATAN - record reviews - concert calendar texEcstasy My wife traveled to Denton last month to give a keynote address at North Texas State University, the first such plenary 979Represent is a local magazine talk she’s given as a tenure track professor. It is also the first time she has entered the state since she moved for the discerning dirtbag. away from Texas last summer. Upon asking her how her visit was she answered, “the talk was good, Texas is ugly”. I snickered at that. My wife has never liked any- Editorial bored where we’ve lived excepting the Pacific Northwest and Kelly Menace - Kevin Still now the Smoky Mountain Carolinas. I too was in the state at the same time as her except I was attending Art Splendidness LOUD!FEST. But she’s not entirely wrong. Breezing into Katie Killer - Wonko Zuckerberg central Texas for a few days in late May is the wrong way Print jockey to experience Texas, especially if one’s usual ambient Craig mack wilkins view is of mountains, forests, and winding streams. Central Texas is ugly. There’s not much going on. Eek- Folks That Did the Other Shit For Us ing out a living in the Brazos Valley has never been a CREEPY HORSE - tim danger - mike l. downey - Jorge business for the aesthete. -

Sunn O Flight of the Behemoth Rar

Sunn O Flight Of The Behemoth Rar Sunn O Flight Of The Behemoth Rar 1 / 3 .,mn 0 01 05_1 1 10 100 10th 11 11_d0003 12 13 14 141a 143b 15 16 17 17igp 18 ... Fleisher Fleks Fleming Fletcher Fleur Fleurette Flight Flip Flo Flo1 Flood Flora ... behaviour behead beheading beheld behemoth behest behind behindhand ... rapturousness raq rar rare rarebit rarefaction rarefactional rarefactive rarefied .... ... fifth highest lake employees sell pacific 31 mostly reason flight square overall ... di ok protecting electrical mubarak colombian uefa o wireless du inhabitants ... trumpeter sdp behemoth seizes uplifting 48-hour arrays pba analytics krause ... phuong hirshhorn rar immunisation naresh juliano marzano haslem bogeying ... Bj rn Rosenstr m-Pop P Svenska-REPACK-SE-2004-GaYfAc.rar (Metal) Black Label Society-Hangover ... Sunn O)))-Flight Of The Behemoth-2002-DNR (Metal) sunn flight behemoth sunn flight behemoth, sunn o))) flight of the behemoth vinyl, sunn o flight of the behemoth review, sunn o))) flight of the behemoth rar, sunn o))) – 3 flight of the behemoth, sunn flight of the behemoth vinyl Oct 30, 2011 — amazing and beautiful, ripped by rain : 320/RAR/MU · armeur H à 17:00 1 commentaire: Partager. 2011-10-10. SUNN O))) - DISCOGRAPHY 1997-2007 (update & fixed june 2012)) ... 2002 - Flight Of The Behemoth 2003 - The .... Jan 30, 2008 — 1998 - The Grimmrobe Demos (Demo) 2000 - 00 Void 2002 - Flight Of The Behemoth 2003 - The Libations Of Samhain (Live EP) 2003 - Veils It .... ... Lamb of God ~ Wrath; Sunn O))) ~ (初心) GrimmRobes Live 101008; Sunn O))) ~ 3: Flight Of The Behemoth; Sunn O))) ~ Altar (with Boris); Sunn O))) ~ Angel ... -

KUHLMANN-THESIS-2018.Pdf (1.113Mb)

FEMALE METAL FANS AND THE PERCEIVED POSITIVE EFFECTS OF METAL MUSIC A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master In the Department of Educational Psychology and Special Education University of Saskatchewan By Anna Noura Kuhlmann Copyright Anna Noura Kuhlmann, January 2018. All rights reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Educational Psychology and Special Education 28 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 0X1 Canada OR Dean College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies University of Saskatchewan 105 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 5A2 Canada i ABSTRACT Despite increasing literature that confirms the therapeutic benefits of music, metal music is still stigmatized as sexist, masculine, and detrimental to its fans. -

Black Metal Excerpt

IF MAYHEM VOCALIST Pelle “Dead” Ohlin had been influential in life, then so was he in death, and many active participants have commented that his premature death provided a turning point for the Norwegian scene, which from then on moved toward even greater extremity. Black metal was now becoming a matter of life and death—or at least was being portrayed as such by Euronymous. Far from grieving, Euronymous appeared to be actively capitalizing on Dead’s death, something that disgusted Necrobutcher, the only member who traveled to Sweden for the funeral. Infamously, Euronymous considered eating parts of Dead’s brain, but claimed that he changed his mind due to its condition. As he stated in The Sepulchral Voice zine, “I have never tried human flesh. We were going to try it when Dead died but he had been lying a little too long.” Instead he and Hellhammer fashioned fragments ofv Dead’s skull into necklaces, with further pieces sent to other friends and contacts of the band, including Morgan of Marduk and Christophe “Masmiseim” Mermod of Samael. More controversially, the pair developed the images of Dead’s body that had been taken by Euronymous, who openly planned to use these for Mayhem artwork. “I must add that it was interesting to be able to study (half) a human brain and rigor mortis,” he explained in one letter. “The pictures will be used on the Mayhem album.” “I think the way people took it was absolutely wrong,” recalls Metalion. “No one re- ally had an idea what was going on, so it was hard for people to deal with this in a proper way. -

Detsember 2019 Detsember : Number Esimene Üheksakümne Nüüdiskultuuri Häälekandja Nüüdiskultuuri

NÜÜDISKULTUURI HÄÄLEKANDJA ÜHEKSAKÜMNE ESIMENE NUMBER : DETSEMBER 2019 HIND 2€ 2 : ÜHEKSAKÜMNE ESIMENE RITUAALNUMBER TOIMETUS SISUKORDRITUAAL / LUULE DETSEMBER 2019 : 3 Kaisa Kuslapuu ja Joosep Vesselov PÜHAD TOIMINGUD JA HINGERAHU Foto: Ken MürkFoto: Ken SISUKORD Kui uurisime selle lehenumbri tarvis erinevatelt inimes- gemus, näiteks lahutus, haigus või telt, mida rituaal nende jaoks tähendab, kirjeldati huvita- lähedase surm. Ent ilma kogenud val kombel ennekõike argiseid harjumusi, millel on muude juhatuseta võivad sellised eluras- toimetuste kõrval tähenduslik roll – olgu siis tegu hommi- kused inimese sootuks ummik- kukohvi joomiseks aja võtmisega või muul moel teadvus- teele viia. tatud hingetõmbega enne tegudele asumist. Samuti on Kindlaksmääratud kombestikuga RITUAAL Nii kulm märkimisväärne, et meenutati ennekõike omaette tehta- rituaalid pakuvad üleminekufaasis Kaisa Kuslapuu JUHTKIRI vaid toiminguid. Kollektiivseid rituaale näikse meie seku- olevale inimesele kindlustunnet SOTSIAALIA laarses ühiskonnas vähem teadvustatavat või isegi pigem ja selgust ning moodsas postmo- Rituaalid rahvuse kestmise teenistuses – omal viisil peljatavat, kuigi see ei väljendu näiteks laulu- ja tantsupeo dernistlikus maailmas võib rituaali Marge Allandi [6–7] pidustustest osavõtus. Iseasi kui paljud mõtestavad seda eestvedajaks olla nii preester, ma jõulupeole teel rahvusliku rituaalina. Umbusu juuri seoses kollektiivsete šamaan kui ka psühholoog. Aga ZEN kuid turritavad laubalt rituaalsete kombetalitustega võib ehk otsida ajaloost, kus seda eeldusel,