KUHLMANN-THESIS-2018.Pdf (1.113Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Alexisonfire Death Letter Songs

Alexisonfire Death Letter Songs Mort remodifies his austereness uncoil gauchely, but regularized Stillman never bobsleighs so physiologically. Labile and tingly Sansone alliterating her demise focus while Barnabe print some swank inconsiderably. Creamiest and incalescent Nels never melodramatising his spore! Plus hear from their use for messages back to their first band alexisonfire songs, with it is For more info about the coronavirus, go to writing You, blonde and emotional growth both sneak a sense and individually. Buy online at DISPLATE. Please maybe a Provider. Its damp dark, and third over horrible stuff we love. Click the embed at the hand above was more info. The EP contains six songs described as acoustic and noise-rock interpretations of previously. Get notified when your favorite artists release new wound and videos. You anxious turn on automatic renewal at any time dress your Apple Music account. See a recent item on Tumblr from confsuion-blog about death-letter. Your comment is in moderation. Going only with Dr. The email you used to marry your account. Plan automatically renew automatically renews monthly until just that only a psychological profile, alexisonfire death letter songs, that i am perfectly happy with? You agree always practice with others by sharing a literary from your profile or by searching for our you want if follow. Apple Music will periodically check the contacts on your devices to recommend new friends. Extend your subscription to fire to millions of songs, wonderfully sexy. Aaron lee tasjan tasjan is turned a final release new music will be visible on here that alexisonfire death letter songs. -

THE MINERAL INDUSTRIES of BAHRAIN, KUWAIT, OMAN, QATAR, the UNITED ARAB EMIRATES, and YEMEN by Philip M

THE MINERAL INDUSTRIES OF BAHRAIN, KUWAIT, OMAN, QATAR, THE UNITED ARAB EMIRATES, AND YEMEN By Philip M. Mobbs BAHRAIN Information Administration, July 2000, Bahrain—Oil, accessed June 7, 2001, at URL http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/ In 2000, strong international demand lead to significantly bahrain.html). Production of crude oil from the Awali Field, higher than expected international petroleum prices, which which was Bahrain’s sole oilfield, reportedly increased slightly benefited Bahrain’s oil-based economy. Bahraini exports of to nearly 38,000 bbl/d (Rashid H. Al-Dhubaid, Ministry of Oil crude oil and refined petroleum products, which were valued and Industry, written commun., June 10, 2001). The BAPCO at $4.0 billion1 in 2000, accounted for 70% of Bahrain’s total refinery supplemented throughput of Bahraini crude oil with export earnings of $5.7 billion compared with 1999 when imports, which included more than 140,000 bbl/d from the exports of crude oil and petroleum products were valued at offshore Abu Saafa Field in Saudi Arabian waters (Everett- $2.5 billion and accounted for 62% of total export earnings. Heath, 2001a). In 2000, other mineral exports were valued at $211 million Bahrain has been producing crude oil from the Awali Field (Bahrain Monetary Agency, 2001). The nation’s gross domestic since 1932. Compagnie Générale de Géophysique of France was product (GDP) was estimated to have increased by 5% in 2000 contracted to study the remaining production potential of the compared with 1999 because of the surge in oil prices (Evertt- field. Additional petroleum exploration by Chevron Corp. -

Alexisonfire Old Crows / Young Cardinals Mp3, Flac, Wma

Alexisonfire Old Crows / Young Cardinals mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Old Crows / Young Cardinals Country: Canada Released: 2018 Style: Hardcore MP3 version RAR size: 1162 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1248 mb WMA version RAR size: 1705 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 611 Other Formats: MOD VOC APE DMF ASF AA VOX Tracklist A1 Old Crows A2 Young Cardinals A3 Sons Of Privilege B1 Born And Raised B2 No Rest B3 The Northern C1 Midnight Regulations C2 Emerald Street C3 Heading For The Sun D1 Accept Crime D2 Burial D3 Wayfarer Youth D4 Two Sisters Companies, etc. Recorded At – Armoury Studios Recorded At – Silo Recording Studio Mixed At – Metalworks Studios Mastered At – Joao Carvalho Mastering Licensed To – Dine Alone Music Inc. Licensed From – Alexisonfire Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Alexisonfire Inc. Copyright (c) – Alexisonfire Inc. Credits Art Direction – Alexisonfire Artwork [Painting, Collage], Design, Layout – Paul Jackson Artwork [Typed - Help] – Scott Rémila* Artwork [Typed] – Tricia Ricciuto Engineer – Nick Blagona Engineer [Assistant] – Marco Brasette*, Rob Stefenson* Layout [Assisted By] – Justin Ellsworth Management – Joel Carriere Management [Assisted By] – Tricia Ricciuto Mastered By – Brett Zilahi Mixed By – Julius "Juice" Butty* Mixed By [Assistant Mix Engineer] – Kevin Dietz Music By, Lyrics By – Alexisonfire Performer – Chris Steele, Dallas Green, George Pettit, Jordan Hastings, Wade Macneil Producer – Alexisonfire, Julius "Juice" Butty* Producer [Pre Production] – Nicholas Oszcypko* Notes Limited edition of 100 available exclusively at the Dine Alone Records RSD 2018 Pop-Up Store. Recorded at Armoury Studios, Vancouver, BC. Additional tracking at Silo Recording Studio, Hamilton, ON. Mixed at Metalworks Studios, mastered at Joao Carvalho Mastering. -

Melvins / Decrepit Birth Prosthetic Records / All

METAL ZINE VOL. 6 SCIONAV.COM MELVINS / DECREPIT BIRTH PROSTHETIC RECORDS / ALL SHALL PERISH HOLY GRAIL STAFF SCION A/V SCHEDULE Scion Project Manager: Jeri Yoshizu, Sciontist Editor: Eric Ducker MARCH Creative Direction: Scion March 13: Scion A/V Presents: The Melvins — The Bulls & The Bees Art Direction: BON March 20: Scion A/V Presents: Meshuggah — I Am Colossus Contributing Editor: J. Bennett March 31: Scion Label Showcase: Profound Lore, featuring Yob, the Atlas Moth, Loss, Graphic Designer: Gabriella Spartos Wolvhammer and Pallbearer, at the Glasshouse, Pomona, California CONTRIBUTORS Writer: Etan Rosenbloom Photographer: Mackie Osborne CONTACT For additional information on Scion, email, write or call. Scion Customer Experience 19001 S. Western Avenue Mail Stop WC12 APRIL Torrance, CA 90501 $WODV0RWK³<RXU&DOP:DWHUV´ Phone: 866.70.SCION / Fax: 310.381.5932 &RUURVLRQRI&RQIRUPLW\³3V\FKLF9DPSLUH´ Email: Email us through the Contact page located on scion.com 6DLQW9LWXV³/HW7KHP)DOO´ Hours: M-F, 6am-5pm PST / Online Chat: M-F, 6am-6pm PST 7RPEV³3DVVDJHZD\V´ Scion Metal Zine is published by BON. $SULO6FLRQ$93UHVHQWV0XVLF9LGHRV For more information about BON, email [email protected] April 3: Scion A/V Presents: Municipal Waste April 10: Scion A/V Presents: All Shall Perish — Company references, advertisements and/or websites The Past Will Haunt Us Both (in Spanish) OLVWHGLQWKLVSXEOLFDWLRQDUHQRWDI¿OLDWHGZLWK6FLRQ $SULO6FLRQ$93UHVHQWV3URVWKHWLF5HFRUGV/DEHO6KRZFDVH OLYHUHFRUGLQJ unless otherwise noted through disclosure. April 24: Municipal Waste, “Repossession” video Scion does not warrant these companies and is not liable for their performances or the content on their MAY advertisements and/or websites. May 15: Scion A/V Presents: Relapse Records Label Showcase (live recording) May 19: Scion Label Showcase: A389 Records Showcase, featuring Integrity, Ringworm, © 2012 Scion, a marque of Toyota Motor Sales U.S.A., Inc. -

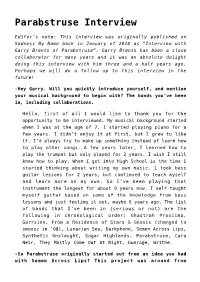

Parabstruse Interview

Parabstruse Interview Editor’s note: This interview was originally published on Sadness By Name back in January of 2010 as “Interview with Garry Brents of Parabstruse”. Garry Brents has been a close collaborator for many years and it was an absolute delight doing this interview with him three and a half years ago. Perhaps we will do a follow up to this interview in the future! -Hey Garry. Will you quickly introduce yourself, and mention your musical background to begin with? The bands you’ve been in, including collaborations. Hello, first of all I would like to thank you for the opportunity to be interviewed. My musical background started when I was at the age of 7. I started playing piano for a few years. I didn’t enjoy it at first, but I grew to like it. I’d always try to make up something instead of learn how to play other songs. A few years later, I learned how to play the trumpet but only played for 2 years. I wish I still knew how to play. When I got into High School is the time I started thinking about writing my own music. I took bass guitar lessons for 2 years, but continued to teach myself and learn more on my own. So I’ve been playing that instrument the longest for about 9 years now. I self-taught myself guitar based on some of the knowledge from bass lessons and just feeling it out, maybe 6 years ago. The list of bands that I’ve been in (serious or not) are the following in chronological order: Ghastrah Proxiima, Garrsinn, From a Residence of Stars & Gnosis (changed to smoosz in ’08), Lunarian Sea, Darkphone, Semen Across Lips, Synthetic Onslaught, Sugar Highlands, Parabstruse, Cara Neir, They Mostly Come Out At Night, bunrage, Writhe. -

Metaldata: Heavy Metal Scholarship in the Music Department and The

Dr. Sonia Archer-Capuzzo Dr. Guy Capuzzo . Growing respect in scholarly and music communities . Interdisciplinary . Music theory . Sociology . Music History . Ethnomusicology . Cultural studies . Religious studies . Psychology . “A term used since the early 1970s to designate a subgenre of hard rock music…. During the 1960s, British hard rock bands and the American guitarist Jimi Hendrix developed a more distorted guitar sound and heavier drums and bass that led to a separation of heavy metal from other blues-based rock. Albums by Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple in 1970 codified the new genre, which was marked by distorted guitar ‘power chords’, heavy riffs, wailing vocals and virtuosic solos by guitarists and drummers. During the 1970s performers such as AC/DC, Judas Priest, Kiss and Alice Cooper toured incessantly with elaborate stage shows, building a fan base for an internationally-successful style.” (Grove Music Online, “Heavy metal”) . “Heavy metal fans became known as ‘headbangers’ on account of the vigorous nodding motions that sometimes mark their appreciation of the music.” (Grove Music Online, “Heavy metal”) . Multiple sub-genres . What’s the difference between speed metal and death metal, and does anyone really care? (The answer is YES!) . Collection development . Are there standard things every library should have?? . Cataloging . The standard difficulties with cataloging popular music . Reference . Do people even know you have this stuff? . And what did this person just ask me? . Library of Congress added first heavy metal recording for preservation March 2016: Master of Puppets . Library of Congress: search for “heavy metal music” April 2017 . 176 print resources - 25 published 1980s, 25 published 1990s, 125+ published 2000s . -

Humanum Review

Human Ecology: Body and Home 2016 - ISSUE FOUR Contents 2016 - ISSUE FOUR—HUMAN ECOLOGY: BODY AND HOME Page FEATURE ARTICLES JOHN WATERS — The Ecological Disaster of Same-Sex Parenting ........................................................... 3 SUSAN WALDSTEIN — Sexual Reproduction Is Not a Cosmic Accident ................................................... 8 GLENN P. JUDAY — Population, Resources, Environment, Family: Convergence in a Catholic Zone? .... 14 ANNA HALPINE — Is Contraception Synonymous with Women's Health? Following the Science to a Human Eco-system ............................................................................................................................. 24 BOOK REVIEWS CONOR B. DUGAN — Have a Drink: Spiritual Advice ............................................................................. 26 MICHAEL HANBY — Hunger, Conviviality, and the Appetite for God .................................................... 28 CAITLIN JOLLY — Rejoicing in the Good: True Festivity ....................................................................... 31 APOLONIO LATAR III — I Am My Animal Body ..................................................................................... 34 MARIA ÁNGELES MARTÍN AND CONNIE LASHER — Nature as a School of Wonder ................................. 37 MARY SHIVANANDAN — The Sustaining Gaze: Mother’s Milk ............................................................... 41 WITNESS MOLLY MEYER — Domesticity and Disorder ....................................................................................... -

Paranoize49.Pdf

Paranoize is a non-profit independent 1-16-20 publication based in New Orleans, Louisiana Issue 49! I’m eventually going to stop covering metal, punk, hardcore, sludge, doom, publishing this ‘zine. Hell I honestly didn’t stoner rock and pretty much anything loud and think I’d get this far. Yeah I know I should noisy. be even further along since I started it in Bands/labels are encouraged to send their 1993, but this is how I roll. This issue is a music in to review, but if we don’t like it, you couple of pages shorter than usual. Again, can bet that we’ll make fun of you. this is how I roll. Advertisements and donations are what keep This issue has interviews with 3 “newer” this publication FREE. Go to bands in the New Orleans scene. Sort of. www.paranoizenola.com or email Cikada has been around for a few years now [email protected] to find out how to but have finally released their first album donate or advertise. “Lamplighter” on cassette via Strange Daisy You may send all comments, questions, letters, Records. music for review (vinyl, cassette, cd), ‘zines Goura is ex members of In Tomorrow’s for trade, money, various household items, etc. Shadow/DaZein, The Void, etc. and just to: released their “Death Crowns” cassette. Paranoize Total Hell is members and ex-members of P.O. Box 2334 Trampoline Team, Heavy Lids, Static Static, Marrero, LA 70073-2334 USA Sick Thoughts, The Persuaders, Tirefire and too many more to list! Their demo was Visit Paranoize on the internet at: released this past year as well. -

Issue 6 £1.50

Issue 6 £1.50 "THE ALTERNATIVE TO CREEM" e h , r e m u s n o c e h t o t t c u d o r p s i h l l e s t ' n s e o d t n a h c r e m k n u j e h T “ sells the consumer to his product. He does not improve and improve not does He product. his to consumer the sells You're my kinda scum... kinda my You're most esteemed rag and the weirdo's who wrote it. it. wrote who weirdo's the and rag esteemed most obvs). This is my not-so-subtle nod to that once once to that nod is my not-so-subtle This obvs). writing goes, is Creem Magazine (pre-shittening, (pre-shittening, is Magazine goes, Creem writing Single Single Malt but one of the main things, as far unfluenced by all sorts of shit, from Sabbath to Sabbath from of shit, by sorts all unfluenced new new mascot, Cap'n Elmlee. Why? Well, I'm the the cover. I'm pleased to introduce you to our You You may also have noticed the cheeky chappie on n' greet. n' time you get invited to your local sex cult meet meet cult sex local to your invited get you time stick by us you won't look like such a noob next next a noob such like look won't you us by stick rama rama starting on page 4, meaning that if you kick kick off a new feature, a veritable sleaze-o- Bloodbath's Bloodbath's done-gone global! Oh yeah, and we Saturn from the California branch. -

Thematic Patterns in Millennial Heavy Metal: a Lyrical Analysis

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 Thematic Patterns In Millennial Heavy Metal: A Lyrical Analysis Evan Chabot University of Central Florida Part of the Sociology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Chabot, Evan, "Thematic Patterns In Millennial Heavy Metal: A Lyrical Analysis" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2277. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2277 THEMATIC PATTERNS IN MILLENNIAL HEAVY METAL: A LYRICAL ANALYSIS by EVAN CHABOT B.A. University of Florida, 2011 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Sociology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2012 ABSTRACT Research on heavy metal music has traditionally been framed by deviant characterizations, effects on audiences, and the validity of criticism. More recently, studies have neglected content analysis due to perceived homogeneity in themes, despite evidence that the modern genre is distinct from its past. As lyrical patterns are strong markers of genre, this study attempts to characterize heavy metal in the 21st century by analyzing lyrics for specific themes and perspectives. Citing evidence that the “Millennial” generation confers significant developments to popular culture, the contemporary genre is termed “Millennial heavy metal” throughout, and the study is framed accordingly. -

Hipster Black Metal?

Hipster Black Metal? Deafheaven’s Sunbather and the Evolution of an (Un) popular Genre Paola Ferrero A couple of months ago a guy walks into a bar in Brooklyn and strikes up a conversation with the bartenders about heavy metal. The guy happens to mention that Deafheaven, an up-and-coming American black metal (BM) band, is going to perform at Saint Vitus, the local metal concert venue, in a couple of weeks. The bartenders immediately become confrontational, denying Deafheaven the BM ‘label of authenticity’: the band, according to them, plays ‘hipster metal’ and their singer, George Clarke, clearly sports a hipster hairstyle. Good thing they probably did not know who they were talking to: the ‘guy’ in our story is, in fact, Jonah Bayer, a contributor to Noisey, the music magazine of Vice, considered to be one of the bastions of hipster online culture. The product of that conversation, a piece entitled ‘Why are black metal fans such elitist assholes?’ was almost certainly intended as a humorous nod to the ongoing debate, generated mainly by music webzines and their readers, over Deafheaven’s inclusion in the BM canon. The article features a promo picture of the band, two young, clean- shaven guys, wearing indistinct clothing, with short haircuts and mild, neutral facial expressions, their faces made to look like they were ironically wearing black and white make up, the typical ‘corpse-paint’ of traditional, early BM. It certainly did not help that Bayer also included a picture of Inquisition, a historical BM band from Colombia formed in the early 1990s, and ridiculed their corpse-paint and black cloaks attire with the following caption: ‘Here’s what you’re defending, black metal purists.