Urban Floods and Case Studies Project: an Overview 1 Anil K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anchoring Heritage with History—Minto Hall

Oprint from & PER is published annually as a single volume. Copyright © 2014 Preservation Education & Research. All rights reserved. Articles, essays, reports and reviews appearing in this journal may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, except for classroom and noncommercial use, including illustrations, in any form (beyond copying permitted by sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law), without written permission. ISSN 1946-5904 PRESERVATION EDUCATION & RESEARCH Preservation Education & Research (PER) disseminates international peer-reviewed scholarship relevant to historic environment education from fields such as historic EDITORS preservation, heritage conservation, heritage studies, building Jeremy C. Wells, Roger Williams University and landscape conservation, urban conservation, and cultural ([email protected]) patrimony. The National Council for Preservation Education (NCPE) launched PER in 2007 as part of its mission to Rebecca J. Sheppard, University of Delaware exchange and disseminate information and ideas concerning ([email protected]) historic environment education, current developments and innovations in conservation, and the improvement of historic environment education programs and endeavors in the United BOOK REVIEW EDITOR States and abroad. Gregory Donofrio, University of Minnesota Editorial correspondence, including manuscripts for ([email protected]) submission, should be emailed to Jeremy Wells at jwells@rwu. edu and Rebecca Sheppard at [email protected]. Electronic submissions are encouraged, but physical materials can be ADVISORY EDITORIAL BOARD mailed to Jeremy Wells, SAAHP, Roger Williams University, One Old Ferry Road, Bristol, RI 02809, USA. Articles Steven Hoffman, Southeast Missouri State University should be in the range of 4,500 to 6,000 words and not be Carter L. Hudgins, Clemson University/College of Charleston under consideration for publication or previously published elsewhere. -

Zooplankton Diversity of Freshwater Lakes of Chennai, Tamil Nadu with Reference to Ecosystem Attributes

International Journal of Int. J. of Life Science, 2019; 7 (2):236-248 Life Science ISSN:2320-7817(p) | 2320-964X(o) International Peer Reviewed Open Access Refereed Journal Original Article Open Access Zooplankton diversity of freshwater lakes of Chennai, Tamil Nadu with reference to ecosystem attributes K. Altaff* Department of Marine Biotechnology, AMET University, Chennai, India *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Manuscript details: ABSTRACT Received: 18.04.2019 Zooplankton diversity of twelve water bodies of Chennai with reference to Accepted: 05.05.2019 variation during pre-monsoon, monsoon, post-monsoon and summer Published: 20.06.2019 seasons is investigated and reported. Out of 49 zooplankton species recorded, 27 species belonged to Rotifera, 10 species to Cladocera, 9 Editor: Dr. Arvind Chavhan species to Copepoda and 3 species to Ostracoda. The Rotifers dominated compared to all other zooplankton groups in all the seasons. However, the Cite this article as: diversity of zooplankton varied from season to season and the maximum Altaff K (2019) Zooplankton diversity was recorded in pre- monsoon season while minimum was diversity of freshwater lakes of observed in monsoon season. The common and abundant zooplankton in Chennai, Tamil Nadu with reference these water bodies were Brachionus calyciflorus, Brchionus falcatus, to ecosystem attributes, Int. J. of. Life Brachionus rubens, Asplancna brightwelli and Lecane papuana (Rotifers), Science, Volume 7(2): 236-248. Macrothrix spinosa, Ceriodaphnia cornuta, Diaphnosoma sarsi and Moina micrura (Cladocerans), Mesocyclops aspericornis Thermocyclops decipiens Copyright: © Author, This is an and Sinodiaptomus (Rhinediaptomus) indicus (Copepods) and Stenocypris open access article under the terms major (Ostracod). The density of the zooplankton was high during pre- of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial - No monsoon and post-monsoon period than monsoon and summer seasons. -

Thiruvallur District

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR 2017 TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT tmt.E.sundaravalli, I.A.S., DISTRICT COLLECTOR TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT TAMIL NADU 2 COLLECTORATE, TIRUVALLUR 3 tiruvallur district 4 DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT - 2017 INDEX Sl. DETAILS No PAGE NO. 1 List of abbreviations present in the plan 5-6 2 Introduction 7-13 3 District Profile 14-21 4 Disaster Management Goals (2017-2030) 22-28 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability analysis with sample maps & link to 5 29-68 all vulnerable maps 6 Institutional Machanism 69-74 7 Preparedness 75-78 Prevention & Mitigation Plan (2015-2030) 8 (What Major & Minor Disaster will be addressed through mitigation 79-108 measures) Response Plan - Including Incident Response System (Covering 9 109-112 Rescue, Evacuation and Relief) 10 Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 113-124 11 Mainstreaming of Disaster Management in Developmental Plans 125-147 12 Community & other Stakeholder participation 148-156 Linkages / Co-oridnation with other agencies for Disaster 13 157-165 Management 14 Budget and Other Financial allocation - Outlays of major schemes 166-169 15 Monitoring and Evaluation 170-198 Risk Communications Strategies (Telecommunication /VHF/ Media 16 199 / CDRRP etc.,) Important contact Numbers and provision for link to detailed 17 200-267 information 18 Dos and Don’ts during all possible Hazards including Heat Wave 268-278 19 Important G.Os 279-320 20 Linkages with IDRN 321 21 Specific issues on various Vulnerable Groups have been addressed 322-324 22 Mock Drill Schedules 325-336 -

Region PINCODES Discription Area Svc DP ETAIL SOUTH 2 515872

Region PINCODES Discription Area Svc DP ETAIL SOUTH 2 515872 HERIAL YBL YBL YES YES SOUTH 2 621704 ARIYALUR CEMENT FACTORY ALR ALR YES YES SOUTH 2 621713 PILIMISAI ALR ALR YES YES SOUTH 2 621802 JAYANKONDA CHOLAPURAM JKM JKM YES YES SOUTH 2 621803 EARAVANGUDI CB JKM JKM YES YES SOUTH 2 621804 THATHANUR JKM JKM YES YES SOUTH 2 587101 BAGALKOT BAZAR BAG BAG YES YES SOUTH 2 587102 BAGALKOT BAG BAG YES YES SOUTH 2 587103 BAGALKOT HOUSING COL BAG BAG YES YES SOUTH 2 587104 BAGALKOT UHS CAMPUS S.O BAG BAG YES YES SOUTH 2 587111 HERKAL BIL BIL YES YES SOUTH 2 587113 SORGAON MUH MUH YES YES SOUTH 2 587114 BALLOLLI BDM BDM YES YES SOUTH 2 587116 BILGI (BAGALKOT) BIL BIL YES YES SOUTH 2 587118 TIMMAPUR IKL IKL YES YES SOUTH 2 587119 HUNNUR JAM JAM YES YES SOUTH 2 587122 LOKAPUR MUH MUH YES YES SOUTH 2 587124 TALLIKERI IKL IKL YES YES SOUTH 2 587125 ILKAL IKL IKL YES YES SOUTH 2 587154 TUMBA IKL IKL YES YES SOUTH 2 587201 BADAMI BDM BDM YES YES SOUTH 2 587203 GULDEGUDDA BDM BDM YES YES SOUTH 2 587204 KALADGI BAG BAG YES YES SOUTH 2 587205 KATAGERI BDM BDM YES YES SOUTH 2 587301 JAMKHANDI JAM JAM YES YES SOUTH 2 587311 RABKAVI BANHATTI BNT BNT YES YES SOUTH 2 587312 SAIDAPUR BNT BNT YES YES SOUTH 2 587313 YADAHALLI MUH MUH YES YES SOUTH 2 587314 RAMPUR BNT BNT YES YES SOUTH 2 587315 TERDAL JAM JAM YES YES SOUTH 2 587316 SAMEERWADI MUH MUH YES YES SOUTH 2 560018 AZAD NAGAR TR MILLS BLR JNR YES YES SOUTH 2 560024 HEBBAL AGRICULTURAL BLR MYT YES YES SOUTH 2 560029 BISMILLANAGAR BLR BXZ YES YES SOUTH 2 560039 NAYANDAHALLI BLR RRN YES YES SOUTH 2 560043 H R B R LAYOUT BLR CGM YES YES SOUTH 2 560045 GOVINDPURAM BLR MYT YES YES SOUTH 2 560059 R.V. -

SCS-CN Method for Surface Runoff Calculation of Agricultural Watershed Area of Bhojtal Priyanka Dwivedi1, Abhishek Mishra2, Sateesh Karwariya3*, Sandeep Goyal4, T

SGVU J CLIM CHANGE WATER Vol. 4, 2017 pp. 9-12 Dwivedi et al. SGVU J CLIM CHANGE WATER Vol. 1 (2), 9-12 ISSN: 2347-7741 SCS-CN Method for Surface Runoff Calculation of Agricultural Watershed Area of Bhojtal Priyanka Dwivedi1, Abhishek Mishra2, Sateesh Karwariya3*, Sandeep Goyal4, T. Thomas5 1Research Trainee Centre for policy Studies, Associated with MPCST, Bhopal 2Research Associate Madhya Pradesh Council of Science and Technology, Bhopal (MP) 3*Research Associate Indian Institute of Soil Science, Bhopal (MP) 4Principle Scientist Madhya Pradesh Council of Science and Technology, Bhopal (MP) 5Scientist ‘C’ National Institute of Hydrology WALMI Campus, Bhopal *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Upper Lake, (Bhojtal) is situated in the city Bhopal.Upper Lake is the major source of water for the city Bhopal. Economic as well as recreational activities of the city Bhopal are dependent on the water availability in the upper Bhopal Lake. This receives water as surface runoff only during monsoon period of each and every year. The upper lake has a catchment area of 375.55km2. The Land use Pattern of about 80% of the catchment is an agricultural area. Whereas 5% is of the forest and rest comes in urban area. Since the inset of monsoon in the catchment area is by 15th June in every year. The agricultural area starts contributing by the end of august. Whereas the lake start receiving surface runoff right from the beginning of monsoon season. Bhojtal Basin has a good surface hydro environment potential to reduce the water scarcity problem of the district. -

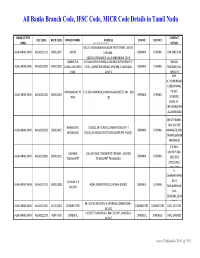

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

Adv. No. 12/2019, Cat No. 65, Junior Programer, SKIL DEVELOPMENT and INDUSTRIAL TRAINING DEPARTMENT, HARYANA Evening Session

Adv. No. 12/2019, Cat No. 65, Junior Programer, SKIL DEVELOPMENT AND INDUSTRIAL TRAINING DEPARTMENT, HARYANA Evening Session Q1. A. B. C. D. Q2. A. B. C. D. Q3. A. B. C. D. Q4. A. B. C. D. Q5. A. B. C. D. February 23, 2020 Page 1 of 26 Adv. No. 12/2019, Cat No. 65, Junior Programer, SKIL DEVELOPMENT AND INDUSTRIAL TRAINING DEPARTMENT, HARYANA Evening Session Q6. __________ is the synonym of "JOIN." A. Release B. Attach C. Disconnect D. Detach Q7. __________ is the antonym of "SYMPATHETIC." A. Insensitive B. Thoughtful C. Caring D. Compassionate Q8. Identify the meaning of the idiom "Miss the boat." A. Let too much time go by to complete a task. B. Long for something that you don't have. C. Miss out on an opportunity. D. Not know the difference between right and wrong. Q9. The sentence has an incorrect phrase, which is in bold and underlined. Select the option that is the correct phrase to be replaced so that the statement is grammatically correct. "I train to be a pilot because my dream is to join the Air Force." A. am training B. would train C. are training D. will have trained Q10. Complete the sentence by choosing the correct form of the verb given in brackets. I was very grateful that he _____ (repair) my computer so promptly. A. repairs B. will be repairing C. will repair D. repaired Q11. Which was the capital of Ashoka's empire? A. Ujjain B. Taxila C. Indraprastha D. Pataliputra February 23, 2020 Page 2 of 26 Adv. -

Monsoon Assemblages

MONSOON ASSEMBLAGES ELEMENTS OF THE URBAN HYDROLOGY OF SOUTH CHENNAI Literature Review Author: Michele Vianello Date: February 2017 ProJect Document Number: OV_Vianello_2017A Monsoon Assemblages sis a proJect funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme. Grant Agreement No. 679873. This review looks at the literature regarding the hydrology and the built up environment of South Chennai as well as the different types of knowledge shaped around them. It examines academic papers, books and book chapters originating in a wide variety of disciplines (eg. architecture, social sciences, geography, hydrology) as well as non-academic texts (eg. newspaper articles, official administrative body websites, NGO reports) and maps (eg. from official agencies, academic papers). It particularly attempts to understand how the different monsoonal cycles have been playing a role in shaping the hydrology and the built up environment as well as the different types of knowledge used to interpret them and act upon them, or else how these cycles failed to be effectively captured in the knowledge production. Addressing these themes required to examine a very diverse literature, at times tackling very specific aspects of the issues at hand. A consistent attempt has been made to coherently extract those bits of information and build an overall picture of the area while laying out the context and identifying relevant issues for the Monsoon Assemblages research project. In spite of this, this review does not claim to be a complete investigation on the elements of the hydrology of South Chennai: the objective has been rather that of identifying which gaps, pertinent to the Monsoon Assemblages line of enquiry, will have to be filled as well as scoping the field for the overall research. -

Bhoj Wetland), Bhopal, India

Vol. 6(8), pp. 252-270, August 2014 DOI: 10.5897/JENE2014.0458 Article Number: A0E622247557 ISSN 2006-9847 Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment Copyright © 2014 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/JENE Full Length Research Paper Spatio-temporal variation of the zooplankton community in a tropical wetland (Bhoj Wetland), Bhopal, India Najeeb Ahmad Bhat1*, Ashwani Wanganeo1 and Rajni Raina2 1Department of Environmental Sciences and Limnology, Barkatullah University, Bhopal (M.P) -462026, India. 2Department of Zoology, Government Benazir Science and Commerce College, Bhopal (MP) India. Received 3 July, 2014; Accepted 22 July, 2014 Bhopal, the capital city of the state of Madhya Pradesh, India is famous for its numerous lakes. The Bhoj Wetland is a wetland of international importance (Ramsar Site). In the two years of study period, a total of 82 zooplankton species were recorded from February 2008-January 2010. Out of which 66 species were recorded in the 1st year (2008-2009), and 70 species documented during the 2nd year (2009-2010). The zooplankton population belongs to five major groups namely: Rotifera (46%), followed by Cladocera (34%), Protozoa (10%) and Copepoda and Ostracoda contributing 6 and 4%, respectively. With regards to Rotifera, in the major peak of June 2009 (38 species), was dominated by the various species of Brachionus and Keratella. The population density data revealed that cumulative site mean density ranged from 84 to 1579 Ind. l-1, with an overall mean of 399 Ind. l-1. The 24 months of mean site density indicated a major peak of 1579 Ind. -

Annual Report 2017-18

KALAKSHETRA FOUNDATION 2017 - 2018 ANNUAL REPORT Our Annual Report this year features images and design elements which are from the Rukmini Devi Museum collection. This museum is found within the premises of Kalakshetra and it houses objects, books, writings, photographs, art, sculpture and many other rarities. All these artefacts were collected by Smt. Rukmini Devi during her travels or were gifted to her by friends and well- wishers from across the world. Rukmini Devi Museum Annual Report 2017-2018 INTRODuCTION Founded in the year 1936 by the KALAKSHETRA FOUNDATION legendary cultural ambassador Smt. Rukmini Devi Arundale, Kalakshetra Foundation was declared as an Institution of National Importance by an Act of Parliament in 1993. The pioneering vision of Smt. Rukmini Devi’s philosophical bedrock of ‘art without vulgarity, beauty without cruelty and education without fear’ inspires Kalakshetra. As a leading institution for teaching Bharatanatyam and Carnatic Music in the country, Kalakshetra creates a cultural ambience which nurtures the various units under it, which include the Rukmini Devi College of Fine Arts which is devoted to Bharatanatyam, Carnatic Music and the visual arts. Also,there are two high schools, a centre for weaving and natural dyeing and printing, two libraries that address the knowledge-based needs of students and scholars alike on arts and allied subjects; and a hostel for school and college students. Between April 2017 and March 2018, Kalakshetra Foundation has been involved in a range of activities in consonance with its vision to promote India’s ancient culture and set a standard of true art. Towards this, it has focussed on festivals, workshops, lectures, enhancement of its repertoire, performances, field trips and research and documentation projects as well as hosted several high profile visitors to its campus. -

Urban and Landscape Design Strategies for Flood Resilience In

QATAR UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING URBAN AND LANDSCAPE DESIGN STRATEGIES FOR FLOOD RESILIENCE IN CHENNAI CITY BY ALIFA MUNEERUDEEN A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science in Urban Planning and Design June 2017 © 2017 Alifa Muneerudeen. All Rights Reserved. COMMITTEE PAGE The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Alifa Muneerudeen defended on 24/05/2017. Dr. Anna Grichting Solder Thesis Supervisor Qatar University Kwi-Gon Kim Examining Committee Member Seoul National University Dr. M. Salim Ferwati Examining Committee Member Qatar University Mohamed Arselene Ayari Examining Committee Member Qatar University Approved: Khalifa Al-Khalifa, Dean, College of Engineering ii ABSTRACT Muneerudeen, Alifa, Masters: June, 2017, Masters of Science in Urban Planning & Design Title: Urban and Landscape Design Strategies for Flood Resilience in Chennai City Supervisor of Thesis: Dr. Anna Grichting Solder. Chennai, the capital city of Tamil Nadu is located in the South East of India and lies at a mere 6.7m above mean sea level. Chennai is in a vulnerable location due to storm surges as well as tropical cyclones that bring about heavy rains and yearly floods. The 2004 Tsunami greatly affected the coast, and rapid urbanization, accompanied by the reduction in the natural drain capacity of the ground caused by encroachments on marshes, wetlands and other ecologically sensitive and permeable areas has contributed to repeat flood events in the city. Channelized rivers and canals contaminated through the presence of informal settlements and garbage has exasperated the situation. Natural and man-made water infrastructures that include, monsoon water harvesting and storage systems such as the Temple tanks and reservoirs have been polluted, and have fallen into disuse. -

Journal of Chemical, Biological and Physical Sciences Seasonal

JCBPS; Section D; November 2019 –January 2020, Vol. 10, No. 1; 053-065. E- ISSN: 2249 –1929 [DOI: 10.24214/jcbps.D.10.1.05365. Journal of Chemical, Biological and Physical Sciences An International Peer Review E-3 Journal of Sciences Available online atwww.jcbsc.org Section D: Environmental Sciences CODEN (USA): JCBPAT Research Article Seasonal Variation in Planktonic Fauna of Sarangpani Pond, Bhopal Pramod Kumar1, Ashwani Wanganeo1 Rajni Raina2 and Fozia Sonaullah1 1Department of Environmental Sciences and Limnology, Barkatullah University, Bhopal, India. 2Department of Zoology, Government Science and Commerce College (Benazir), Bhopal, M.P., India. Received: 10 January 2020; Revised: 24 January 2020; Accepted: 30 January 2020 Abstract: Present study was aimed to assess the zooplankton diversity and entire ecological condition of Sarangpani pond of Bhopal city. Total of 78 zooplankton species were recorded from the ponds waters during two years of study period which consisted of Rotifera 29 species (37%), Cladocera &Protozoa 16 species each (20% each), Copepoda 13 species (17%) and Ostracoda 4 species (5%). Among all the zooplankton classes, species belongs to the class Rotifera were recorded their dominance during both the years of study. The dominance of Rotifers population in terms of quality has been recorded. Seasonal variation of zooplankton population recorded maximum species diversity of class Rotifera during summer (1st year) and winter season (2nd year). On the other hand, minimum population density was contributed by class Copepoda in all the season. Presence of various pollution indicator zooplankton species indicates and evidences the high anthropogenic pressure and direct mixing sewage from the nearby catchment in the pond waters which has accelerated the eutrophication in the Sarangpani pond.