Monsoon Assemblages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zooplankton Diversity of Freshwater Lakes of Chennai, Tamil Nadu with Reference to Ecosystem Attributes

International Journal of Int. J. of Life Science, 2019; 7 (2):236-248 Life Science ISSN:2320-7817(p) | 2320-964X(o) International Peer Reviewed Open Access Refereed Journal Original Article Open Access Zooplankton diversity of freshwater lakes of Chennai, Tamil Nadu with reference to ecosystem attributes K. Altaff* Department of Marine Biotechnology, AMET University, Chennai, India *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Manuscript details: ABSTRACT Received: 18.04.2019 Zooplankton diversity of twelve water bodies of Chennai with reference to Accepted: 05.05.2019 variation during pre-monsoon, monsoon, post-monsoon and summer Published: 20.06.2019 seasons is investigated and reported. Out of 49 zooplankton species recorded, 27 species belonged to Rotifera, 10 species to Cladocera, 9 Editor: Dr. Arvind Chavhan species to Copepoda and 3 species to Ostracoda. The Rotifers dominated compared to all other zooplankton groups in all the seasons. However, the Cite this article as: diversity of zooplankton varied from season to season and the maximum Altaff K (2019) Zooplankton diversity was recorded in pre- monsoon season while minimum was diversity of freshwater lakes of observed in monsoon season. The common and abundant zooplankton in Chennai, Tamil Nadu with reference these water bodies were Brachionus calyciflorus, Brchionus falcatus, to ecosystem attributes, Int. J. of. Life Brachionus rubens, Asplancna brightwelli and Lecane papuana (Rotifers), Science, Volume 7(2): 236-248. Macrothrix spinosa, Ceriodaphnia cornuta, Diaphnosoma sarsi and Moina micrura (Cladocerans), Mesocyclops aspericornis Thermocyclops decipiens Copyright: © Author, This is an and Sinodiaptomus (Rhinediaptomus) indicus (Copepods) and Stenocypris open access article under the terms major (Ostracod). The density of the zooplankton was high during pre- of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial - No monsoon and post-monsoon period than monsoon and summer seasons. -

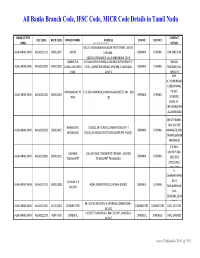

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

Urban and Landscape Design Strategies for Flood Resilience In

QATAR UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING URBAN AND LANDSCAPE DESIGN STRATEGIES FOR FLOOD RESILIENCE IN CHENNAI CITY BY ALIFA MUNEERUDEEN A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science in Urban Planning and Design June 2017 © 2017 Alifa Muneerudeen. All Rights Reserved. COMMITTEE PAGE The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Alifa Muneerudeen defended on 24/05/2017. Dr. Anna Grichting Solder Thesis Supervisor Qatar University Kwi-Gon Kim Examining Committee Member Seoul National University Dr. M. Salim Ferwati Examining Committee Member Qatar University Mohamed Arselene Ayari Examining Committee Member Qatar University Approved: Khalifa Al-Khalifa, Dean, College of Engineering ii ABSTRACT Muneerudeen, Alifa, Masters: June, 2017, Masters of Science in Urban Planning & Design Title: Urban and Landscape Design Strategies for Flood Resilience in Chennai City Supervisor of Thesis: Dr. Anna Grichting Solder. Chennai, the capital city of Tamil Nadu is located in the South East of India and lies at a mere 6.7m above mean sea level. Chennai is in a vulnerable location due to storm surges as well as tropical cyclones that bring about heavy rains and yearly floods. The 2004 Tsunami greatly affected the coast, and rapid urbanization, accompanied by the reduction in the natural drain capacity of the ground caused by encroachments on marshes, wetlands and other ecologically sensitive and permeable areas has contributed to repeat flood events in the city. Channelized rivers and canals contaminated through the presence of informal settlements and garbage has exasperated the situation. Natural and man-made water infrastructures that include, monsoon water harvesting and storage systems such as the Temple tanks and reservoirs have been polluted, and have fallen into disuse. -

Environmental and Social Systems Assessment Report March 2021

Chennai City Partnership Program for Results Environmental and Social Systems Assessment Report March 2021 The World Bank, India 1 2 List of Abbreviations AIIB Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank AMRUT Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission BMW Bio-Medical Waste BOD Biological Oxygen Demand C&D Construction & Debris CBMWTF Common Bio-medical Waste Treatment and Disposal Facility CEEPHO Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation CETP Common Effluent Treatment Plant CMA Chennai Metropolitan Area CMDA Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority CMWSSB Chennai Metro Water Supply and Sewage Board COD Chemical Oxygen Demand COE Consent to Establish COO Consent to Operate CPCB Central Pollution Control Board CRZ Coastal Regulation Zone CSCL Chennai Smart City Limited CSNA Capacity Strengthening Needs Assessment CUMTA Chennai Unified Metropolitan Transport Authority CZMA Coastal Zone Management Authority dBA A-weighted decibels DoE Department of Environment DPR Detailed Project Report E & S Environmental & Social E(S)IA Environmental (and Social) Impact Assessment E(S)MP Environmental (and Social) Management Plan EHS Environmental, Health & Safety EP Environment Protection (Act) ESSA Environmental and Social Systems Assessment GCC Greater Chennai Corporation GDP Gross Domestic Product GL Ground Level GoTN Government of Tamil Nadu GRM Grievance Redressal Mechanism HR Human Resources IEC Information, Education and Communication ICC Internal Complaints Committee JNNRUM Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission -

Archive of Vol. XV No. 14, November 1-15, 2005

Reg. No. TN/PMG (CCR) /814/04-05 Licence No. WPP 506/04-05 Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI R.N. 53640/91 INSIDE Promoting tree culture Preserving heritage MADRAS The homes of Mylapore Flavours of South India MUSINGS Only one grabbed chance Rs. 5 per copy Vol. XV No. 14 November 1-15, 2005 (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) Mumbai ruling food for Chennai thought? Appa, theyve given me an additional 1000 minutes of free talk-time... Now Ive only got to find friends to talk to! n a landmark decision on October 17th, the Bombay High I Court ruled against the sale of mill lands in Central Bombay for Talks cheap large-scale commercial development. Mobile users, persistently wooed The land belonged to five National Textile Corporation Mills and by mobile service providers, are had been sold to bidding developers. The Court ruled that one-third a happy lot today. of the land should be used for low-cost housing, another third as Phones are easily available, and open space and only the rest for commercial development. with free talk times, they can In the Bombay judgment there is much that is of relevance of chatter all night. (Right like Chennai in what has gone on, and is NOW going on apace, in the we, as a nation, need to be Adyar Estuary and its surroundings. But will anyone concerned coaxed to talk more and with building development in Chennai pay any attention to what we longer.) report below on the Mumbai case? But what will this constant THE EDITOR staying-in-touch do to us? (Compiled from reports by D. -

INDIA the Economic Scenario

` ` 6/2020 INDIA Contact: Rajesh Nath, Managing Director Please Note: Jamly John, General Manager Telephone: +91 33 40602364 1 trillion = 100,000 crores or Fax: +91 33 23217073 1,000 billions 1 billion = 100 crores or 10,000 lakhs E-mail: [email protected] 1 crore = 100 lakhs 1 million= 10 lakhs The Economic Scenario 1 Euro = Rs.82 Economic Growth As per the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), India’s economy could prove the most resilient in South Asia and its large market will continue to attract market-seeking investments to the country even as it expects a dramatic fall in global foreign direct investment (FDI). However, inflows may shrink sharply. India jumped to ninth spot in 2019 on the list of global top FDI recipients from the twelfth spot in 2018. Due to the Covid-19 crisis, global FDI flows are forecast to nosedive by upto 40% in 2020, from their 2019 value of € 1.40 ($1.54) trillion, bringing FDI below € 0.91 ($1) trillion for the first time since 2005. FDI is projected to decrease by a further 5-10% in 2021 and a recovery is likely in 2022 amid a highly uncertain outlook. A rebound in 2022, with FDI reverting to the pre-pandemic underlying trend, is possible, but only at the upper bound of expectations. The outlook looks highly uncertain. FDI inflows into India rose 13% on year in FY20 to a record € 45 ($49.97) billion compared to € 40 ($44.36) billion in 2018-19. In 2019, FDI flows to the region declined by 5%, to € 431 ($474) billion, despite gains in South East Asia, China and India. -

Vol XVII MM 01.Pmd

Registered with the Reg. No. TN/PMG (CCR) /814/06-08 Registrar of Newspapers Licence to post without prepayment for India under R.N.I. 53640/91 Licence No. WPP 506/06-08 Rs. 5 per copy (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI INSIDE Short N Snappy Kotturpuram in the 60s MADRAS Travellers tales Presidency College buildings MUSINGS The Birth of Round Table Vol. XVII No. 01 April 16-30, 2007 Can Adyar Creek eco park ignore estuary? (By A Special Correspondent) ow can you ensure a On December 22, 2003, the Hsuccessful eco park with- State Government handed over I am missing you so much and out sustaining its feed water sys- 58 acres of the area to the citys dont know what to do without you tems and the natural wealth Corporation to develop it into darling! around it? Thats the question an eco park modelled on Bye bye love, that has to be answered before Tezozomac in Mexico. Entries hello . peace! work can begin on the Adyar to the park were planned from Bags are packed, ill-used teens Creek Eco Park. Greenways Road and South Ca- sulking over not being al- Chennai is one of the few cit- nal Bank Road. The GO speci- lowed to take a certain outfit ies in the world to have a large fied that the flow of water along The new enclosure for the proposed eco park. (Its too much for your expanse of wetlands within it. the Creek would not be dis- grandparents, dear) are The Adyar Creek, a natural es- turbed, no concrete construc- the conservation of hicle (SPV), Adyar Creek Eco smiling again, AWOL tick- tuarine ecosystem, extends over tion would be allowed and that waterbodies. -

Phyto-Remediation of Urban Lakes in and Around Chennai

ISSN: 0974-2115 www.jchps.com Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sciences Phyto-remediation of urban lakes in and around Chennai G.Priyanga, B.Abhirami, N.R.Gowri* Meenakshi Sundararajan Engineering College, Chennai, India *Corresponding Author: E.Mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Phyto-remediation is an environmental friendly technique which uses plants to improve the condition of the contaminated ecology by absorbing the contaminants. In this research, we have used Water Hyacinth to remediate the waters of Ambattur, Retteri and Korattur. The removal of Lead (Pb), Copper (Cu), Cadmium (Cd) and Iron (Fe) is examined through a model system. These heavy metals were chosen due to their repercussions under high concentration. Batch treatment method is adopted and assessed for 4 weeks. The parameters are tested using Atomic absorption spectroscopy equipment and the results are compared. The results obtained show that water hyacinth is efficient enough in removing almost 95% of harmful heavy metals from urban lake sample. Key words: Green techniques, Phyto-remediation, Water, Plants, Urban lakes, Pollution INTRODUCTION Water is one of the most important constituents needed by living organisms for their day-to-day survival. Even though water is present abundantly on the earth, only 2.5% of it is available to us as freshwater. One of the most important sources of freshwater is lakes which are getting highly contaminated due to increasing urbanization, rapid industrialization and intensification of pesticides in agricultural activities using pesticides. The pollutants are commonly removed through chemical precipitation, reverse osmosis and solvent extraction. These techniques have disadvantages such as incomplete metal removal, high reagent and energy requirements, generation of toxic sludge or other waste products that again require further treatment if required necessary. -

Newletter113125944301.Pdf

8-13 of his classical work, ‘Confessions’ with an open request to all of Archbishop Speaks.... us to do the same: PRAYING FOR THE DEAD IN OUR FAMILY PRAYERS “And inspire, O my Lord my God, inspire Your servants my brethren, Your sons my masters, who with voice and heart and writings I serve, that so many of them as shall read these confessions may at Your The month of November brings with it the privileged responsibility altar remember Monica, Your handmaid, by whose flesh You introduced and opportunity to pray for the departed members of our families and me into this life, in what manner I know not. That so my mother’s last friends. I would like to indicate a few points for our continued reflection entreaty to me may, through my confessions more than through my on the relation between this traditional aspect of our faith with our prayers, be more abundantly fulfilled to her through the prayers of reflections on ‘Family Prayer’. many.” (Confessions IX, 13) The tradition of praying for the dead is a concrete expression of our In remembering to pray for the deceased during our family prayers, conviction that those who have passed his earthly life are separated we continue our communion with them; we affirm that they are still from us physically though spiritually they remain connected to us. It is part of our families; and more importantly that death is conquered by an affirmation of the fact that death does not break the bond of our the power of love and prayer. -

49107-003: Tamil Nadu Urban Flagship Investment Program

Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 49107-003 May 2018 IND: Tamil Nadu Urban Flagship Investment Program (TNUFIP) – Providing Comprehensive Sewerage Scheme to Manali, Chinnasekkadu, Karambakkam and Manapakkam in Chennai City Prepared by Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply & Sewerage Board (CMWSSB), Government of Tamil Nadu for the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 18 April 2018) Currency unit – Indian rupee (₹) ₹1.00 – $0.0152 $1.00 = ₹65.6826 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ASI – Archeological Survey of India CMSC – Construction Management and Supervision Consultant CPCB – Central Pollution Control Board CTE – consent to establish CTO – consent to operate DWC – double wall corrugated EAC – Expert Appraisal Committee EHS – Environmental, Health and Safety EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan IEE – initial environmental examination MOEFCC – Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change NOC – No Objection Certificate PIU – Project -

10Th Social Study Material

Namma Kalvi www.nammakalvi.in tuyhW go¥ngh« ! . òéæaš go¥ngh« ! . tuyhW gil¥ngh« ! . ónfhs¤ij MŸnth« ! . 10 Social Science EnglishMedium 2019 – 2020 Guide for 100 % result Tamil Nadu History Teachers Association Written & Designed by sTUDENT’S FRIEND SOCIAL SCIENCE ENTHUSIAST M. MUNEESWARAN M. A. B.Ed GHS, Iluppaikudi, Devakottai Sivagangai District. Cell No.8072507357 and Social Science Teachers Family www.nammakalvi.in g¤jh« tF¥ò r_f m¿éaš òÂa ghl¤Â£l¤Âš bghJ¤nj®Î vGj¥ nghF« khzt khzéfS¡F thœ¤J¡fŸ. Kj‰f© Áwªj kÂ¥bg© bgwΫ vëjhf nj®éš bt‰¿ailΫ F¿¥ò¡fŸ c§fS¡fhf ! . édh¤jhŸ IªJ gFÂfshf mikªJŸsJ. Kjš Ãçéš 14 rçahd éilia nj®Î brŒJ vGj nt©L«. Ïu©lh« Ãçéš édh v© 15 Kjš 28 tiu Ïu©L kÂ¥bg© édh¡fshf mikªJŸsJ. mt‰WŸ 28 tJ édh f£lha édhthf cŸsJ. nk‰f©l Ïu©lh« Ãçéš tuyhW - 4 òéæaš - 4 Foikæaš - 2 bghUëaš - 2 vd nf£l 14 š 10 édh¡fŸ vGj nt©L«. gF _‹¿š r‰W é¤Âahrkhd tiugl«, fhy¡nfhL, ntWghL édh¡fŸ cl‹ IªJ kÂ¥bg© fyªj gFÂahf tªJŸsJ. Ïj‹go ϧF édh v© 29 nfho£l Ïl§fŸ ãu¥òf, 30 tuyhW bghU¤Jf, 31 òéæaš bghU¤Jf, 32 ntWghL fhuz« TWf, 33 - 34 tuyhW IªJ kÂ¥bg©, 35- 36 òéæaš IªJ kÂ¥bg©, 37 - 38 Foikæaš IªJ kÂ¥bg©, 39 -40 bghUëaš IªJ kÂ¥bg© vdΫ 41 tJ tuyhW fhy¡nfhL tiuf vdΫ, 42 tJ f£lha édhthf, tuyhW cyf tiugl« vdΫ, kh‰W tiuglkhf tuyhW ϪÂah vdΫ tuyh« vd jftš.