The Power of Lace by Gil Dye

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palmetto Tatters Guild Glossary of Tatting Terms (Not All Inclusive!)

Palmetto Tatters Guild Glossary of Tatting Terms (not all inclusive!) Tat Days Written * or or To denote repeating lines of a pattern. Example: Rep directions or # or § from * 7 times & ( ) Eg. R: 5 + 5 – 5 – 5 (last P of prev R). Modern B Bead (Also see other bead notation below) notation BTS Bare Thread Space B or +B Put bead on picot before joining BBB B or BBB|B Three beads on knotting thread, and one bead on core thread Ch Chain ^ Construction picot or very small picot CTM Continuous Thread Method D Dimple: i.e. 1st Half Double Stitch X4, 2nd Half Double Stitch X4 dds or { } daisy double stitch DNRW DO NOT Reverse Work DS Double Stitch DP Down Picot: 2 of 1st HS, P, 2 of 2nd HS DPB Down Picot with a Bead: 2 of 1st HS, B, 2 of 2nd HS HMSR Half Moon Split Ring: Fold the second half of the Split Ring inward before closing so that the second side and first side arch in the same direction HR Half Ring: A ring which is only partially closed, so it looks like half of a ring 1st HS First Half of Double Stitch 2nd HS Second Half of Double Stitch JK Josephine Knot (Ring made of only the 1st Half of Double Stitch OR only the 2nd Half of Double Stitch) LJ or Sh+ or SLJ Lock Join or Shuttle join or Shuttle Lock Join LPPCh Last Picot of Previous Chain LPPR Last Picot of Previous Ring LS Lock Stitch: First Half of DS is NOT flipped, Second Half is flipped, as usual LCh Make a series of Lock Stitches to form a Lock Chain MP or FP Mock Picot or False Picot MR Maltese Ring Pearl Ch Chain made with pearl tatting technique (picots on both sides of the chain, made using three threads) P or - Picot Page 1 of 4 PLJ or ‘PULLED LOOP’ join or ‘PULLED LOCK’ join since it is actually a lock join made after placing thread under a finished ring and pulling this thread through a picot. -

Katherine Kerswell Chief Executive London Borough of Croydon Bernard Weatherill House 8 Mint Walk Croydon CR0 1EA

Katherine Kerswell Chief executive London Borough of Croydon Bernard Weatherill House 8 Mint Walk Croydon CR0 1EA December 17th Dear Katherine Kerswell, Initially, I wrote to Croydon Council on the 27th July to raise concerns about the impact of the LTN scheme. I also spoke to the former Croydon Cabinet Member for transport and expressed my deep concerns with the scheme, as well as having written to the Secretary of State for Transport to raise my concerns and request any further assistance he can provide. Unfortunately, this matter remains a major issue locally - my constituents have continued to be impacted with reports of increased road rage, traffic and road closures. London Borough of Bromley challenged the legality of the LTN scheme, due to the failure of Croydon to consult with LBB before implementing the scheme. I welcomed the news that Croydon Council allowed a formal consultation on the final agreed proposals, allowing residents to comment formally on the proposals. However, I was disappointed to have been informed last week that the consultation was extended by another 14 days as local businesses were not included in the first consultation. It is right that local businesses are consulted, but I had hoped that this would have been done at the outset. The consultation, therefore, ends on Friday and the outcome will not be known until early January causing further delay and distress to those affected. My view remains unchanged, I believe that if a better scheme can work for both Boroughs, it should be trialled first. If this isn’t possible then the current roadblocks should be voted out and the idea abandoned as it simply has not worked in practice. -

Swisstulle AG

Cinte Techtextil China is the ideal trade fair for technical textile and nonwoven products in Asia. This Swisstulle AG year the fair welcomes Swisstulle AG and Swisstulle (Qingdao) Co Ltd from Switzerland to showcase their warp knitted fabric for automobile Swisstulle (Qingdao) Co Ltd sunshade. at Cinte Techtextil China 2021 (Detailed product info featured on page 2.) Visit them at E1 - D01 Swisstulle AG Swisstulle (Qingdao) Co Ltd Company website: https://swisstulle.ch/ Swisstulle is since more than 35 years an important participant in the technical textiles market as a producer of knitting fabrics, as well as a specialist in various finishing processes. In each department well educated and specialized staff is at your disposal in order to realize your specific requirements and specifications. Due to the deep connections between production, product management and sales we are able to fulfill customer requests just in time. Cinte Techtextil China 22 – 24 June 2021 Shanghai New International Expo Centre Developing unique and exclusive Meet Swisstulle AG & Swisstulle products for niche markets (Qingdao) Co Ltd Technical textiles: at Cinte Techtextil China 2021! - Automotive/ Aviation industry (sunblind – safety net) - Medical Textiles - Substrates for coating & gumming- Reinforcement - Silver bobbinet for electro-magnetic "We now have a stable customer group. On the premise of maintaining the current customers, we also hope to get more cooperative relations with enterprises, so as to Swisstulle, the specialist when it comes expand the awareness of our products. We hope to show to textiles! our products to more countries through international trade shows like Cinte Techtextil China, so as to expand our Swisstulle has been present in the worldwide market for reputation and find more potential customers." technical textiles for more than 35 years as a manufacturer and supplier of knitted fabrics. -

NEEDLE LACES Battenberg, Point & Reticella Including Princess Lace 3Rd Edition

NEEDLE LACES BATTENBERG, POINT & RETICELLA INCLUDING PRINCESS LACE 3RD EDITION EDITED BY JULES & KAETHE KLIOT LACIS PUBLICATIONS BERKELEY, CA 94703 PREFACE The great and increasing interest felt throughout the country in the subject of LACE MAKING has led to the preparation of the present work. The Editor has drawn freely from all sources of information, and has availed himself of the suggestions of the best lace-makers. The object of this little volume is to afford plain, practical directions by means of which any lady may become possessed of beautiful specimens of Modern Lace Work by a very slight expenditure of time and patience. The moderate cost of materials and the beauty and value of the articles produced are destined to confer on lace making a lasting popularity. from “MANUAL FOR LACE MAKING” 1878 NEEDLE LACES BATTENBERG, POINT & RETICELLA INLUDING PRINCESS LACE True Battenberg lace can be distinguished from the later laces CONTENTS by the buttonholed bars, also called Raleigh bars. The other contemporary forms of tape lace use the Sorrento or twisted thread bar as the connecting element. Renaissance Lace is INTRODUCTION 3 the most common name used to refer to tape lace using these BATTENBERG AND POINT LACE 6 simpler stitches. Stitches 7 Designs 38 The earliest product of machine made lace was tulle or the PRINCESS LACE 44 RETICELLA LACE 46 net which was incorporated in both the appliqued hand BATTENBERG LACE PATTERNS 54 made laces and later the elaborate Leavers laces. It would not be long before the narrow tapes, in fancier versions, would be combined with this tulle to create a popular form INTRODUCTION of tape lace, Princess Lace, which became and remains the present incarnation of Belgian Lace, combining machine This book is a republication of portions of several manuals made tapes and motifs, hand applied to machine made tulle printed between 1878 and 1938 dealing with varieties of and embellished with net embroidery. -

Bobbin Lace You Need a Pattern Known As a Pricking

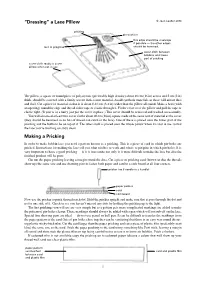

“Dressing” a Lace Pillow © Jean Leader 2014 pricking pin-cushion this edge should be a selvage if possible — the other edges lace in progress should be hemmed. cover cloth between bobbins and lower part of pricking cover cloth ready to cover pillow when not in use The pillow, a square or round piece of polystyrene (preferably high density) about 40 cm (16 in) across and 5 cm (2 in) thick, should be covered with a firmly woven dark cotton material. Avoid synthetic materials as these will attract dust and fluff. Cut a piece of material so that it is about 8-10 cm (3-4 in) wider than the pillow all round. Make a hem (with an opening) round the edge and thread either tape or elastic through it. Fit the cover over the pillow and pull the tape or elastic tight. (If you’re in a hurry just pin the cover in place.) This cover should be removed and washed occasionally. You will also need at least two cover cloths about 40 cm (16 in) square made of the same sort of material as the cover (they should be hemmed so no bits of thread can catch in the lace). One of these is placed over the lower part of the pricking and the bobbins lie on top of it. The other cloth is placed over the whole pillow when it is not in use so that the lace you’re working on stays clean. Making a Pricking In order to make bobbin lace you need a pattern known as a pricking. -

Catalogue of the Famous Blackborne Museum Collection of Laces

'hladchorvS' The Famous Blackbome Collection The American Art Galleries Madison Square South New York j J ( o # I -legislation. BLACKB ORNE LA CE SALE. Metropolitan Museum Anxious to Acquire Rare Collection. ' The sale of laces by order of Vitail Benguiat at the American Art Galleries began j-esterday afternoon with low prices ranging from .$2 up. The sale will be continued to-day and to-morrow, when the famous Blackborne collection mil be sold, the entire 600 odd pieces In one lot. This collection, which was be- gun by the father of Arthur Blackborne In IS-W and ^ contmued by the son, shows the course of lace making for over 4(Xi ye^rs. It is valued at from .?40,fX)0 to $oO,0()0. It is a museum collection, and the Metropolitan Art Museum of this city would like to acciuire it, but hasnt the funds available. ' " With the addition of these laces the Metropolitan would probably have the finest collection of laces in the world," said the museum's lace authority, who has been studying the Blackborne laces since the collection opened, yesterday. " and there would be enough of much of it for the Washington and" Boston Mu- seums as well as our own. We have now a collection of lace that is probablv pqual to that of any in the world, "though other museums have better examples of some pieces than we have." Yesterday's sale brought SI. .350. ' ""• « mmov ON FREE VIEW AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH, NEW YORK FROM SATURDAY, DECEMBER FIFTH UNTIL THE DATE OF SALE, INCLUSIVE THE FAMOUS ARTHUR BLACKBORNE COLLECTION TO BE SOLD ON THURSDAY, FRIDAY AND SATURDAY AFTERNOONS December 10th, 11th and 12th BEGINNING EACH AFTERNOON AT 2.30 o'CLOCK CATALOGUE OF THE FAMOUS BLACKBORNE Museum Collection of Laces BEAUTIFUL OLD TEXTILES HISTORICAL COSTUMES ANTIQUE JEWELRY AND FANS EXTRAORDINARY REGAL LACES RICH EMBROIDERIES ECCLESIASTICAL VESTMENTS AND OTHER INTERESTING OBJECTS OWNED BY AND TO BE SOLD BY ORDER OF MR. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 25 August 2015 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Not peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Johnson, Rachel E. and Armitage, Faith and Spary, Carole and Malley, Rosa (2012) 'A conversation : researching gendered ceremony and ritual in parliaments.', Feminist theory., 13 (3). pp. 325-336. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1464700112456007 Publisher's copyright statement: Johnson, Rachel E. and Armitage, Faith and Spary, Carole and Malley, Rosa (2012) 'A conversation : researching gendered ceremony and ritual in parliaments.', Feminist theory., 13 (3). pp. 325-336. Copyright c 2012 The Author(s). Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Feminist Theory, Vol. 13, Issue 3, pp.325-336. Researching Gendered Ceremony and Ritual in Parliaments In June 2009, John Bercow presided over the British House of Commons in his first session as Speaker. -

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif. -

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identification

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Text copyright © Jeremy Farrell, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name held at The Museum of Costume and Textiles, Nottingham on 21st February 2008. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audiences. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750 -1950 Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740-1890 Front cover image: Detail of a triangular shawl of white cotton Pusher lace made by William Vickers of Nottingham, 1870. The Pusher machine cannot put in the outline which has to be put in by hand or by embroidering machine. The outline here was put in by hand by a woman in Youlgreave, Derbyshire. (NCM 1912-13 © Nottingham City Museums) 2 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Contents Page 1. List of illustrations 1 2. Introduction 3 3. The main types of hand and machine lace 5 4. -

October 2004 CLASSIFICATION DEFINITIONS 87 - 1

October 2004 CLASSIFICATION DEFINITIONS 87 - 1 CLASS 87, TEXTILES: BRAIDING, NETTING, 245, Wire Fabrics and Structure, particularly sub- AND LACE MAKING classes 7 and 8 for wire fabrics even though for a structure provided for in this class (87) hav- SECTION I - CLASS DEFINITION ing claimed additional features of wire fabric structure. Processes and apparatus for forming strands or fabrics 427, Coating Processes, pertinent subclasses as from yarns, filaments or strands, by braiding, knotting determined by schedule review for processes and/or intertwisting the strands; and the corresponding of coating, per se, not combined with a textile products or fabrics. operation. SECTION II - LINES WITH OTHER CLASSES AND WITHIN THIS CLASS SUBCLASSES The line between this Class (87) and Class 428, Stock 1 Coated or impregnated: Material or Miscellaneous Articles, is that any plural This subclass is indented under the class defini- layer product or stock material which includes a compo- tion. Processes involving the applying of a nent classifiable in this Class (87) will be placed in this coating or impregnating material to the product Class; a plural layer stock material or product in general by application to the strand material at any time with no structure of the Class 87 type will be classified (i.e., before, during and/or after) relative to the in Class 428, Stock Material or Miscellaneous Articles. mechanical interrelation of the strands; and the See also reference to Class 87 in the main definition of resulting products. Class 428, Lines With Other Classes, Intermediate Arti- cles, and subclass 592 for metallic stock material having SEE OR SEARCH THIS CLASS, SUB- a helical component. -

Winter Lace Conference

5TH ANNUAL WINTER LACE CONFERENCE February 18-20, 2011 Plus an “add on” additional day with your teacher on February 21 AND EXTRA PRE-CONFERENCE Workshops on February 18 with Louise Colgan, Susie Johnson, and Marji Suhm Hotel Hanford, Costa Mesa, CA Hotel price For more information, contact: same as Betty Ward at 1-714-522-8118 or [email protected] 2007! Belinda Belisle at 1-562-596-7882 or belis92645@aol. com Page 1 Join us for lace classes, vendors, special speakers, and a LOT OF FUN for the . 5th Annual WINTER LACE CONFERENCE! We would like to invite you to be a part of the 5th Annual Winter Lace Conference. In addition to our selection of classes and wonderful teachers, a vendor hall packed with lace Friday, February 18, 2011 EXTRA: Intermediate and supplies, and a special banquet presentation, this year we are Advanced Milanese Workshop pleased to bring you: with Louise Colgan OR Withof Workshop with Susie A special Friday workshop for BEGINNING Johnson FINGER LACERS and INTERMEDIATE and OR ADVANCED MILANESE and WITHOF lacers—and Beginning Greek Finger Lace those wanting one-on-one attention Workshop with Marji Suhm Sunday sit-down, served breakfast! R&R—Registration and Special opening of the vending hall on Friday Reception evening! Vendor Hall Opens We know you will not want to miss the special banquet Saturday, February 19, 2011 presentation by lacemaker and lace historian, Carole Classes McFadzean, on Sunday night. Vendor Hall Luncheon Carol will take you on a historical journey and mystery of lace prickings found in the attic of a school in her area and traced Sunday, February 20, 2011 back to the lace made for Queen Victoria! You will want to Breakfast make a point to attend this special program.