Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swisstulle AG

Cinte Techtextil China is the ideal trade fair for technical textile and nonwoven products in Asia. This Swisstulle AG year the fair welcomes Swisstulle AG and Swisstulle (Qingdao) Co Ltd from Switzerland to showcase their warp knitted fabric for automobile Swisstulle (Qingdao) Co Ltd sunshade. at Cinte Techtextil China 2021 (Detailed product info featured on page 2.) Visit them at E1 - D01 Swisstulle AG Swisstulle (Qingdao) Co Ltd Company website: https://swisstulle.ch/ Swisstulle is since more than 35 years an important participant in the technical textiles market as a producer of knitting fabrics, as well as a specialist in various finishing processes. In each department well educated and specialized staff is at your disposal in order to realize your specific requirements and specifications. Due to the deep connections between production, product management and sales we are able to fulfill customer requests just in time. Cinte Techtextil China 22 – 24 June 2021 Shanghai New International Expo Centre Developing unique and exclusive Meet Swisstulle AG & Swisstulle products for niche markets (Qingdao) Co Ltd Technical textiles: at Cinte Techtextil China 2021! - Automotive/ Aviation industry (sunblind – safety net) - Medical Textiles - Substrates for coating & gumming- Reinforcement - Silver bobbinet for electro-magnetic "We now have a stable customer group. On the premise of maintaining the current customers, we also hope to get more cooperative relations with enterprises, so as to Swisstulle, the specialist when it comes expand the awareness of our products. We hope to show to textiles! our products to more countries through international trade shows like Cinte Techtextil China, so as to expand our Swisstulle has been present in the worldwide market for reputation and find more potential customers." technical textiles for more than 35 years as a manufacturer and supplier of knitted fabrics. -

Cora Ginsburg Catalogue 2015

CORA GINSBURG LLC TITI HALLE OWNER A Catalogue of exquisite & rare works of art including 17th to 20th century costume textiles & needlework 2015 by appointment 19 East 74th Street tel 212-744-1352 New York, NY 10021 fax 212-879-1601 www.coraginsburg.com [email protected] NEEDLEWORK SWEET BAG OR SACHET English, third quarter of the 17th century For residents of seventeenth-century England, life was pungent. In order to combat the unpleasant odors emanating from open sewers, insufficiently bathed neighbors, and, from time to time, the bodies of plague victims, a variety of perfumed goods such as fans, handkerchiefs, gloves, and “sweet bags” were available for purchase. The tradition of offering embroidered sweet bags containing gifts of small scented objects, herbs, or money began in the mid-sixteenth century. Typically, they are about five inches square with a drawstring closure at the top and two to three covered drops at the bottom. Economical housewives could even create their own perfumed mixtures to put inside. A 1621 recipe “to make sweete bags with little cost” reads: Take the buttons of Roses dryed and watered with Rosewater three or foure times put them Muske powder of cloves Sinamon and a little mace mingle the roses and them together and putt them in little bags of Linnen with Powder. The present object has recently been identified as a rare surviving example of a large-format sweet bag, sometimes referred to as a “sachet.” Lined with blue silk taffeta, the verso of the central canvas section contains two flat slit pockets, opening on the long side, into which sprigs of herbs or sachets filled with perfumed powders could be slipped to scent a wardrobe or chest. -

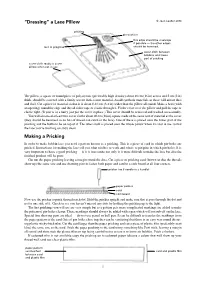

Bobbin Lace You Need a Pattern Known As a Pricking

“Dressing” a Lace Pillow © Jean Leader 2014 pricking pin-cushion this edge should be a selvage if possible — the other edges lace in progress should be hemmed. cover cloth between bobbins and lower part of pricking cover cloth ready to cover pillow when not in use The pillow, a square or round piece of polystyrene (preferably high density) about 40 cm (16 in) across and 5 cm (2 in) thick, should be covered with a firmly woven dark cotton material. Avoid synthetic materials as these will attract dust and fluff. Cut a piece of material so that it is about 8-10 cm (3-4 in) wider than the pillow all round. Make a hem (with an opening) round the edge and thread either tape or elastic through it. Fit the cover over the pillow and pull the tape or elastic tight. (If you’re in a hurry just pin the cover in place.) This cover should be removed and washed occasionally. You will also need at least two cover cloths about 40 cm (16 in) square made of the same sort of material as the cover (they should be hemmed so no bits of thread can catch in the lace). One of these is placed over the lower part of the pricking and the bobbins lie on top of it. The other cloth is placed over the whole pillow when it is not in use so that the lace you’re working on stays clean. Making a Pricking In order to make bobbin lace you need a pattern known as a pricking. -

How to Use Access Commodities Filament Silk Gimp

How to Use Access Commodities Filament Silk Gimp This innovative thread was recreated from 17th century examples found on period needlework. The unique structure of silk gimp consists of a filament silk core wrapped with filament silk. The cord like appearance is both sleek and supple to use, providing an interesting surface texture. It is recommended to treat Filament Silk Gimp like real metal thread passing threads, which are not stitched back and forth through a fabric or canvas, but applied on the surface to great effect. Step 1: First knot the end of the silk gimp before unreeling it off the spool. As you un- reel the silk gimp, it may twist back on itself, due to the composition of the thread. Sim- ply stroke it to smooth it out. Step 2: Unreel a small amount of thread about 4 to 6 inches and snap the top of the spool on the remainder. (See illustration #1) Don’t cut it off the spool but leave it on, unrolling a little more as you stitch. This helps controls the thread as you work and minimizes the twisting. Illustration No. 1 Step 3: The thread can be couched with Au Ver á Soie, Soie 100/3 or a single ply of Au Ver à Soie, Soie de Paris. (See list below for list matching colors.) A Crewel #10 needle is recommended. You will find it helpful if the couching thread is waxed for control. Copyright L. Haidar for Access Commodities, 2013. Date: December 2013 Step 4: Make your couching stitches slanted rather than straight because of the twist of the thread. -

Catalogue of the Famous Blackborne Museum Collection of Laces

'hladchorvS' The Famous Blackbome Collection The American Art Galleries Madison Square South New York j J ( o # I -legislation. BLACKB ORNE LA CE SALE. Metropolitan Museum Anxious to Acquire Rare Collection. ' The sale of laces by order of Vitail Benguiat at the American Art Galleries began j-esterday afternoon with low prices ranging from .$2 up. The sale will be continued to-day and to-morrow, when the famous Blackborne collection mil be sold, the entire 600 odd pieces In one lot. This collection, which was be- gun by the father of Arthur Blackborne In IS-W and ^ contmued by the son, shows the course of lace making for over 4(Xi ye^rs. It is valued at from .?40,fX)0 to $oO,0()0. It is a museum collection, and the Metropolitan Art Museum of this city would like to acciuire it, but hasnt the funds available. ' " With the addition of these laces the Metropolitan would probably have the finest collection of laces in the world," said the museum's lace authority, who has been studying the Blackborne laces since the collection opened, yesterday. " and there would be enough of much of it for the Washington and" Boston Mu- seums as well as our own. We have now a collection of lace that is probablv pqual to that of any in the world, "though other museums have better examples of some pieces than we have." Yesterday's sale brought SI. .350. ' ""• « mmov ON FREE VIEW AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH, NEW YORK FROM SATURDAY, DECEMBER FIFTH UNTIL THE DATE OF SALE, INCLUSIVE THE FAMOUS ARTHUR BLACKBORNE COLLECTION TO BE SOLD ON THURSDAY, FRIDAY AND SATURDAY AFTERNOONS December 10th, 11th and 12th BEGINNING EACH AFTERNOON AT 2.30 o'CLOCK CATALOGUE OF THE FAMOUS BLACKBORNE Museum Collection of Laces BEAUTIFUL OLD TEXTILES HISTORICAL COSTUMES ANTIQUE JEWELRY AND FANS EXTRAORDINARY REGAL LACES RICH EMBROIDERIES ECCLESIASTICAL VESTMENTS AND OTHER INTERESTING OBJECTS OWNED BY AND TO BE SOLD BY ORDER OF MR. -

10/2011 Dress with Galloon Lace Detail By: Burda Style Magazine

10/2011 Dress with galloon lace detail By: burda style magazine http://www.burdastyle.com/projects/102011-dress-with-galloon-lace-detail Dress with galloon lace detail: Galloon lace is a double edge lace with a usable border on both sides that can be separated for matching border trim. burda style magazine patterns FAQ 1 Materials Wool crpe Step 1 — Preparation Paper cut for ANSI A (German DIN A4) prints: This pattern is printed on 8.5″ × 11″ sheets of plain paper. Do not scale or center pages before printing. Wait until all sheets are printed out before beginning to tape them together. Do not cut out pattern pieces yet— Arrange the sheets on a large, hard, flat surface so that they fit together, matching up like numbers and letters (i.e. 6A to 6A). To tape pattern together, fold under the margin of one piece (6A) and tape right against the line of it’s matching number/letter (6A). Trace the pattern pieces from the pattern sheet, follow lines for the respective sizes. The sizes for this dress is 76, 80, 84, 88, 92. 76 / EUR 38 / US 8 80 / EUR 40 / US 10 84 / EUR 42 / US 12 88 / EUR 44 / US 14 92 / EUR 46 / US 16 burda style magazine pattern do not have seam allowance included. Seam and hem allowances to be added: Seams and edges 1.5 cm (5/8 in). Step 2 — Cutting out 2 Cut the following pieces: Main fabric: Pattern piece number 1 – Center front piece, cut on fold x1 Pattern piece number 2 – Side front piece, cut x2 Pattern piece number 3 – Center back piece, cut x2 Pattern piece number 4 – Side back piece, cut x2 Pattern piece number 5 – Sleeve, cut x2 Pattern piece number 6 – Front neck facing, cut x2 Pattern piece number 7 – Back neck facing, cut x2 Lining: Pattern piece number 1 – Center front piece, cut on fold x1 Pattern piece number 2 – Side front piece, cut x2 Pattern piece number 3 – Center back piece, cut x2 Pattern piece number 4 – Side back piece, cut x2 Interfacing: Cut pieces for and iron onto all facing pieces. -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif. -

October 2004 CLASSIFICATION DEFINITIONS 87 - 1

October 2004 CLASSIFICATION DEFINITIONS 87 - 1 CLASS 87, TEXTILES: BRAIDING, NETTING, 245, Wire Fabrics and Structure, particularly sub- AND LACE MAKING classes 7 and 8 for wire fabrics even though for a structure provided for in this class (87) hav- SECTION I - CLASS DEFINITION ing claimed additional features of wire fabric structure. Processes and apparatus for forming strands or fabrics 427, Coating Processes, pertinent subclasses as from yarns, filaments or strands, by braiding, knotting determined by schedule review for processes and/or intertwisting the strands; and the corresponding of coating, per se, not combined with a textile products or fabrics. operation. SECTION II - LINES WITH OTHER CLASSES AND WITHIN THIS CLASS SUBCLASSES The line between this Class (87) and Class 428, Stock 1 Coated or impregnated: Material or Miscellaneous Articles, is that any plural This subclass is indented under the class defini- layer product or stock material which includes a compo- tion. Processes involving the applying of a nent classifiable in this Class (87) will be placed in this coating or impregnating material to the product Class; a plural layer stock material or product in general by application to the strand material at any time with no structure of the Class 87 type will be classified (i.e., before, during and/or after) relative to the in Class 428, Stock Material or Miscellaneous Articles. mechanical interrelation of the strands; and the See also reference to Class 87 in the main definition of resulting products. Class 428, Lines With Other Classes, Intermediate Arti- cles, and subclass 592 for metallic stock material having SEE OR SEARCH THIS CLASS, SUB- a helical component. -

Charles A. Whitaker Auction Co. October 29-30 Session Two Lot 549-1244

Charles A. Whitaker Auction Co. October 29-30 Session Two Lot 549-1244 549 FRENCH CHINOISERIE BROCADE SILK, c. 1740-1750. Four small panels including one pieced, having ivory pattern on raspberry ground. Three pieces 24 wide x 15 1/2, 26 and 31. One 28 1/2 x 17. Holes and tears, fair. $57.50 550 LOT of SILK TEXILES, 18th C. Consisting of a red velvet panel, cushion cover and valance, the valance having shield-form tabs (applique and tassels removed), and a panel with narrow stripes in cream, dusty rose, yellow and green on a tiny checked weave. Fair. $34.50 551 THREE PRINTED COTTON PANELS, 19th C. One striped in teal with small white leaves and white with red and tan botehs, probably Persian. One English floral print. Both excellent. One large pieced panel with pomegranate trees, probably Indian, (oxidizing browns, mends and tears) poor. $103.50 552 BEADED NEEDLEWORK VICTORIAN BELL PULL. Wool flowers with beaded foliage on a ground of crystal beads having a Bohemian glass finial. (Glass cracked, backing shattered, minor bead loss) needlework intact, fair. $230.00 553 LOT of ASSORTED SMALL BEAD and NEEDLEWORK, 18th-19th C. Including two 18th C. petit point rectangles of figures in landscapes, three rectangles of needlework birds, a silk satin embroidered bag having gilt metal doves and chenille bell tassels, two framed 18th C embroideries: one eagle in tree, one basket of fruit. Good-excellent. $345.00 554 TWO PIECED SILK TEXTILES with FLORAL BROCADE, 18th C. Dusty pink damask bedcover with a serpentine floral in pastel hues, backed in blue silk, (some splits, mostly at seams). -

Sew Any Fabric Provides Practical, Clear Information for Novices and Inspiration for More Experienced Sewers Who Are Looking for New Ideas and Techniques

SAFBCOV.qxd 10/23/03 3:34 PM Page 1 S Fabric Basics at Your Fingertips EW A ave you ever wished you could call an expert and ask for a five-minute explanation on the particulars of a fabric you are sewing? Claire Shaeffer provides this key information for 88 of today’s most NY SEW ANY popular fabrics. In this handy, easy-to-follow reference, she guides you through all the basics while providing hints, tips, and suggestions based on her 20-plus years as a college instructor, pattern F designer, and author. ABRIC H In each concise chapter, Claire shares fabric facts, design ideas, workroom secrets, and her sewing checklist, as well as her sewability classification to advise you on the difficulty of sewing each ABRIC fabric. Color photographs offer further ideas. The succeeding sections offer sewing techniques and ForewordForeword byby advice on needles, threads, stabilizers, and interfacings. Claire’s unique fabric/fiber dictionary cross- NancyNancy ZiemanZieman references over 600 additional fabrics. An invaluable reference for anyone who F sews, Sew Any Fabric provides practical, clear information for novices and inspiration for more experienced sewers who are looking for new ideas and techniques. About the Author Shaeffer Claire Shaeffer is a well-known and well- respected designer, teacher, and author of 15 books, including Claire Shaeffer’s Fabric Sewing Guide. She has traveled the world over sharing her sewing secrets with novice, experienced, and professional sewers alike. Claire was recently awarded the prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award by the Professional Association of Custom Clothiers (PACC). Claire and her husband reside in Palm Springs, California. -

The Lacenews Chanel on Youtube October 2011 Update

The LaceNews Chanel on YouTube October 2011 Update http://www.youtube.com/user/lacenews Bobbinlace Instruction - 1 (A-H) 1 1 Preparing bobbins for lace making achimwasp 10/14/2007 music 2 2 dentelle.mpg AlainB13 10/19/2010 silent 3 3 signet.ogv AlainB13 4/23/2011 silent 4 4 napperon.ogv AlainB13 4/24/2011 silent 5 5 Evolution d'un dessin technique d'une dentelle aux fuseaux AlainB13 6/9/2011 silent 6 6 il primo videotombolo alikingdogs 9/23/2008 Italian 7 7 1 video imparaticcio alikingdogs 11/14/2008 Italian 8 8 2 video imparaticcio punto tela alikingdogs 11/20/2008 Italian 9 9 imparaticcio mezzo punto alikingdogs 11/20/2008 Italian 10 10 Bolillos, Anaiencajes Hojas de guipur Blancaflor2776 4/20/2008 Spanish/Catalan 11 11 Bolillos, hojas de guipur Blancaflor2776 4/20/2008 silent 12 12 Bolillos, encaje 3 pares Blancaflor2776 6/26/2009 silent 13 13 Bobbin Lacemaking BobbinLacer 8/6/2008 English 14 14 Preparing Bobbins for Lace making BobbinLacer 8/19/2008 English 15 15 Update on Flower Project BobbinLacer 8/19/2008 English 16 16 Cómo hacer el medio punto - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 17 17 Cómo hacer el punto entero o punto de lienzo - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 18 18 Conceptos básicos - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 19 19 Materiales necesarios - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 20 20 Merletto a fuselli - Introduzione storica (I) casacenina 4/19/2011 Italian 21 21 Merletto a Fuselli - Corso: il movimento dei fuselli (III) casacenina 5/2/2011 Italian 22 -

Hooray for Health Arthur Curriculum

Reviewed by the American Academy of Pediatrics HHoooorraayy ffoorr HHeeaalltthh!! Open Wide! Head Lice Advice Eat Well. Stay Fit. Dealing with Feelings All About Asthma A Health Curriculum for Children IS PR O V IDE D B Y FUN D ING F O R ARTHUR Dear Educator: Libby’s® Juicy Juice® has been a proud sponsor of the award-winning PBS series ARTHUR® since its debut in 1996. Like ARTHUR, Libby’s Juicy Juice, premium 100% juice, is wholesome and loved by kids. Promoting good health has always been a priority for us and Juicy Juice can be a healthy part of any child’s balanced diet. Because we share the same commitment to helping children develop and maintain healthy lives, we applaud the efforts of PBS in producing quality educational television. Libby’s Juicy Juice hopes this health curriculum will be a valuable resource for teaching children how to eat well and stay healthy. Enjoy! Libby’s Juicy Juice ARTHUR Health Curriculum Contents Eat Well. Stay Fit.. 2 Open Wide! . 7 Dealing with Feelings . 12 Head Lice Advice . 17 All About Asthma . 22 Classroom Reproducibles. 30 Taping ARTHUR™ Shows . 32 ARTHUR Home Videos. 32 ARTHUR on the Web . 32 About This Guide Hooray for Health! is a health curriculum activity guide designed for teachers, after-school providers, and school nurses. It was developed by a team of health experts and early childhood educators. ARTHUR characters introduce five units exploring five distinct early childhood health themes: good nutrition and exercise (Eat Well. Stay Fit.), dental health (Open Wide!), emotions (Dealing with Feelings), head lice (Head Lice Advice), and asthma (All About Asthma).