The Tung Wah Times and the Origins of Chinese Australian Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integra Calendar

THe INTEGRA Project is co-funded by the European Union's INTEGRA CALENDAR Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund 2019 01 02 03 04 05 06 1/2 New Year's Day 4 Spring Festival Eve (China) 1 Martisor (Moldova, Romania), Maharishi 1 April Fools 1 Labour Day 1 Children's Day (Moldova, CHina, 4 Youth Day (China) 5 Chinese New Year 4 Independence Day (Senegal) Romania) 7/8 Orthodox Christmas Day Dayanand Saraswati Jayanti (India) 5 Mother's Day (Romania) 5-7 Qing Ming Jie (China) 4 6 Spring Festival Golden Week holiday 6 Memorial Day (Romania), Ramadam Koritè (Senegal) 6 11 Independence Manifesto (Morocco) 1-6 Carnival (Brazil) Chaitra Sukhladi (India) 7 Birthday of Ravindranath (india) 5 Eid al-Fitr, Ramzan Id/Eid-ul-Fitar (China) 9 Day of Valor (philippines), Martyrs' Day 9 Victory Day (Serbia, Moldova, Ukraine), (India) 13 8 Mothers' Day, Longtaitou Festival (China) Guru Govind Singh Jayanti (India) 10 Vasant Panchami (India) (Tunisia) Europe Day (Moldova) 6 Orthodox Ascension (Romania) 10 Monarchy Day (Romania) 14 Revolution and Youth Day (Tunusia) 11 Youth Day 12 Arbor Day (china) 13 Sinhala and Tamil New Year's Eve (Sri 12 Mother's Day (Sri Lanka, Brazil, 7 Dragon Boat Festival (China) Lanka), Special Working Day (Moldova), 14 Valentine's Day Ukraine), Father's Day (Romania) Orthodox New Year 14 Summer Day (Albania) 10 With Monday (Senegal) Rama Navami (India) 13 Special Non-Working Day (Philippines) 15-16 Statehood Day (Serbia) 12 Independence Day (Philippines), 14 Ambedkar Jayanti (India) 15 20 Duruthu Full Moon Poya Day (sri Lanka) 20 -

Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 385 489 SO 025 360 AUTHOR Yu-ning, Li, Ed. TITLE Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240p. AVAILABLE FROM Johnson & Associates, 257 East South St., Franklin, IN 46131-2422 (paperback: $25; clothbound: ISBN-1-880938-008, $39; shipping: $3 first copy, $0.50 each additional copy). PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chinese Culture; *Cultural Images; Females; Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Legends; Mythology; Role Perception; Sexism in Language; Sex Role; *Sex Stereotypes; Sexual Identity; *Womens Studies; World History; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Asian Culture; China; '`Chinese Literature ABSTRACT This book examines the ways in which Chinese literature offers a vast array of prospects, new interpretations, new fields of study, and new themes for the study of women. As a result of the global movement toward greater recognition of gender equality and human dignity, the study of women as portrayed in Chinese literature has a long and rich history. A single volume cannot cover the enormous field but offers volume is a starting point for further research. Several renowned Chinese writers and researchers contributed to the book. The volume includes the following: (1) Introduction (Li Yu- Wing);(2) Concepts of Redemption and Fall through Woman as Reflected in Chinese Literature (Tsung Su);(3) The Poems of Li Qingzhao (1084-1141) (Kai-yu Hsu); (4) Images of Women in Yuan Drama (Fan Pen Chen);(5) The Vanguards--The Truncated Stage (The Women of Lu Yin, Bing Xin, and Ding Ling) (Liu Nienling); (6) New Woman vs. -

Holiday Sales Calendar China

Important Marketing Holidays of the China JANUARY 01 FEBRUARY 02 MARCH 03 01 New Year’s Day 05 Chinese Lunar New Year's Day 08 International Women's Day 24-25 Spring Festival 08 Lantern Festival 14 White Day 25 Chinese New Year 14 Valentine’s Day 15 Consumer Rights Day 28 Earth hour day APRIL 04 MAY 05 JUNE 06 01 April Fool’s Day 01 Labor Day 01 Children’s Day 04 Qingming Festival 10 Mother’s Day 25 Dragon Boat Festival 17 517 Festival 10-12 CES Asia 20 Online Valentine’s Day 18 618 Shopping Festival 21 Father’s Day JULY 07 AUGUST 08 SEPTEMBER 09 24 Tokyo Olympics will Begin 03 Men’s Day 10 Teacher’s Day 30 International Day of Friendship 08 Closing of the Tokyo Olympics 15 Harvest Celebration 25 Qixi / Chinese Valentine's Day Back to School Sales (Whole Month) OCTOBER 10 NOVEMBER 11 DECEMBER 12 01 Mid-autumn Festival 11 Single’s Day / Double Eleven 12 Double Twelve 01-07 National Day Golden Week 27 Black Friday 21 Winter Solstice 24 China Programmer Day 26 Thanksgiving Day 25 Christmas Day 25 Double Ninth Festival 30 Cyber Monday 31 Halloween https://www.mconnectmedia.com/blog/category/holiday-sales/ https://www.mconnectmedia.com/magento-2-extensions https://www.mconnectmedia.com/blog/category/holiday-sales/ https://www.mconnectmedia.com/magento-2-extensions Holidayhttps://www.mconnectmedia.com/blog/category/holiday-sales/ Sales Tips Magento Extensions https://www.mconnectmedia.com/blog/category/trends-and-statistics/ https://www.mconnectmedia.com/magento-developers-for-hire https://www.mconnectmedia.com/blog/category/trends-and-statistics/Latest eCommerce Trends Hirehttps://www.mconnectmedia.com/magento-developers-for-hire Magento Developer For more information visit - www.mconnectmedia.com https://www.mconnectmedia.com https://www.mconnectmedia.com. -

Holidays and Observances, 2020

Holidays and Observances, 2020 For Use By New Jersey Libraries Made by Allison Massey and Jeff Cupo Table of Contents A Note on the Compilation…………………………………………………………………….2 Calendar, Chronological……………….…………………………………………………..…..6 Calendar, By Group…………………………………………………………………………...17 Ancestries……………………………………………………....……………………..17 Religion……………………………………………………………………………….19 Socio-economic……………………………………………………………………….21 Library……………………………………...…………………………………….…...22 Sources………………………………………………………………………………....……..24 1 A Note on the Compilation This listing of holidays and observances is intended to represent New Jersey’s diverse population, yet not have so much information that it’s unwieldy. It needed to be inclusive, yet practical. As such, determinations needed to be made on whose holidays and observances were put on the calendar, and whose were not. With regards to people’s ancestry, groups that made up 0.85% of the New Jersey population (approximately 75,000 people) and higher, according to Census data, were chosen. Ultimately, the cut-off needed to be made somewhere, and while a round 1.0% seemed a good fit at first, there were too many ancestries with slightly less than that. 0.85% was significantly higher than any of the next population percentages, and so it made a satisfactory threshold. There are 20 ancestries with populations above 75,000, and in total they make up 58.6% of the New Jersey population. In terms of New Jersey’s religious landscape, the population is 67% Christian, 18% Unaffiliated (“Nones”), and 12% Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and Hindu. These six religious affiliations, which add up to 97% of the NJ population, were chosen for the calendar. 2% of the state is made up of other religions and faiths, but good data on those is lacking. -

Holidays Top Famous Numbers Chinese – – – – – Day3 Day4 Day5 Day1 Day2 Week1 Week2 Week3 Week4 Agenda Holidays in China Useful Words for Mandarin Entry Day 3 Holidays

知 行 Gee Sing Mandarin 汉 语 Agenda Week1 Phonetic Transcription Week2 Tones and rules Week3 Strokes and writing Week4 Useful words Day1 – Numbers Day2 – Chinese Zodiac Day3 – Holidays in China Day4 – Top cities Day5 – Famous attractions Holidays in China Useful words for Mandarin Entry Day 3 Holidays jié rì 节日 The traditional Chinese holidays are an essential part of harvests or prayer offerings. The most important Chinese holiday is the Chinese New Year (Spring Festival), which is also celebrated in Taiwan and overseas ethnic Chinese communities. All traditional holidays are scheduled according to the Chinese calendar. Day 3 Holidays chú xī 除夕 dà nián sān shí 大年三十 Chinese New Year Eve, Last day of lunar year Family get together and celebrate the end of the year. Usually, we stay up to midnight to embrace the lunar new year. The elderly will give lucky money(红hóng包bāo) to the young generations. Day 3 Holidays chūn jié 春节 dà nián chū yī 大年初一 Chinese New Year (Spring Festival), The first day of January (lunar calendar) Set off fireworks after midnight; visit family members; Many ceremonies and celebration activities. Day 3 Holidays yuán xiāo jié 元宵节 zhēng yuè shí wǔ 正月十五 Lantern Festival , Fifteenth day of January (lunar calendar) Lantern parade and lion dance celebrating the first full moon. Eating 汤圆(tāngyuán). This day is also the last day of new year celebration. Day 3 Holidays qīng míng jié 清明节 sì yuè wǔ rì 四月五日 Qingming Festival (Tomb Sweeping Festival, Tomb Sweeping Day, Clear and Bright Festival) Visit, clean, and make offerings at ancestral gravesites, spring outing Day 3 Holidays duān wǔ jié 端午节 wǔ yuè chū wǔ 五月初五 Duanwu Festival (Dragon Boat Festival), Fifth day of May (lunar calendar) Dragon boat race, eat sticky rice wrapped in lotus leaves 粽子(zòngzǐ). -

Research on the Customs of Festival Sports Entertainment in Tang Dynasty from Angles of Poems and Proses

International Academic Workshop on Social Science (IAW-SC 2013) Research on the Customs of festival sports entertainment in Tang Dynasty from Angles of Poems and Proses Junli Yu Department of Sports Media and Cultural Studies Xi’an Physical Education University Xi’an 710068,China e-mail: [email protected] Abstract—This paper textually investigates festival sports and recreational custom in the Tang Dynasty—its origin, II. FESTIVAL SPORTS AND RECREATIONAL CUSTOMS underlying cultural implication, spectacularity and evolution A. Ascending a height on Man Day in the Tang Dynasty by document research method. There were a great number of festivals at that time to stage so many Man Day had been celebrated before the Tang Dynasty. colorful festival folk custom activities,such as Man Day, Festivals in Jinchu Area records, “Man Day is celebrated on Shangyuan Festival, Shangsi Festival (3rd day of 3rd lunar January 7 (lunar calendar)… when people ascend a height month),Qingming Festival and Cold Food Day,Dragon Boat and compose poetic proses.”[2] This is the very festival Festival, Double Ninth Festival,Lari Festival,Winter Solstice which is themed by human, demonstrating the rich cultural Festival and New Year’s Eve.Some Poems and Proses of the implications of valuing human, birth and new things, which Tang Dynasty feature festival sports and recreational activities, apparently were enriched and developed in such a vigorous presenting clear pictures of such spectacular events and society of the Tang Dynasty. helping preserve our fine folk customs, their rites and more. On Man Day, plants begin to sprout in new spring, and if the weather was cooperative, people in the Tang Dynasty Keywords—the Tang Dynasty; Sports; Poems and Proses; usually ascended a height for celebration. -

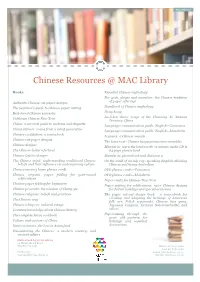

Chinese Resources @ MAC Library

China Bib 0517 Chinese Resources @ MAC Library Books Essential Chinese mythology For gods, ghosts and ancestors: the Chinese tradition of paper offerings Authentic Chinese cut-paper designs The beginner’s guide to Chinese paper cutting Handbook of Chinese mythology Best-loved Chinese proverbs Hong Kong La-li-lou dance songs of the Chuxiong Yi, Yunnan Celebrate Chinese New Year Province, China China: a survival guide to customs and etiquette Language communication guide: English—Cantonese China witness: voices from a silent generation Language communication guide: English—Mandarin Chinese civilization: a sourcebook Legacies: a Chinese mosaic Chinese cut-paper designs The lions roar: Chinese luogu percussion ensembles Chinese designs Mandarin: learn the basics with 71-minute audio CD & The Chinese lantern festival 64 page phrase book Chinese Lattice designs Mandarin: phrasebook and dictionary The Chinese mind: understanding traditional Chinese On the smell of an oily rag: speaking English, thinking beliefs and their influence on contemporary culture Chinese and living Australian Chinese nursing home phrase cards OYO phrase cards—Cantonese Chinese origami: paper folding for year-round OYO phrase cards—Mandarin celebrations Paper crafts for Chinese New Year Chinese paper folding for beginners Paper cutting for celebrations: 100+ Chinese designs Chinese proverbs: the wisdom of Cheng-yu for festive holidays and special occasions Chinese religions: beliefs and practices The paper cut-out design book : a sourcebook for The Chinese way creating -

Spring Festival Or Chinese New Year (Chun Fie) -The First Day of First Lunar

The dragon in Chinese culture is a symbol of the etheric force, the master of all elements. There is a dragon in the water, in the fire, in the earth, and in the snow, etc. People will gain the protection from such etheric force or gain growing and life forces from celebrating and worshiping the Dragon. We can see the dragon appear in many festival celebrations such as the Spring Festival, Dragon Head Lifting Festival, and Dragon Boat Festival. The Dao (Tao) had a Yery strong influence on people's life and culture in the past. Some festival celebrations also have to do with Dao. The food, the time, and the procedures of ceremony have to follow certain regulations of Yi |ing or fengshui. The ways in which Chinese festivals were celebrated in the past were quite rich and diverse. Of course' the main parts were wonderful banquets and family gatherings. Sharing a particular food is a way to show our gratitude to nature, earth and heaven. The family gathering and performing some kind of ceremony are ways to express our gratitude to the family, the ancestors, and the gods. In addition to eating, having special rituals, the process of making food, d.ecorating the house, making crafts, playing special games, wearing fine clothes, parades of dragon dances, an4 dance were also elements of traditional celebrations in the old times according ti the different parts of China. Today, a festive celebration only consists of a banquet and family gathering and not much ceremony or ritual. Especially the younger generation no longer has much experience of the old ways of celebrating festivals. -

Holiday Calendar 2021 Rough Draft

Holidays and Observances, 2021 For Use By New Jersey Libraries Made by Allison Massey and Jeff Cupo Table of Contents A Note on the Compilation…………………………………………………………………….2 Calendar, Chronological……………….…………………………………………………..…..6 Calendar, By Group…………………………………………………………………………...16 Ancestries……………………………………………………....……………………..16 Religion……………………………………………………………………………….18 Socio-economic……………………………………………………………………….20 Library……………………………………...…………………………………….…...21 Sources………………………………………………………………………………....……..22 1 A Note on the Compilation This listing of holidays and observances is intended to represent New Jersey’s diverse population, yet not have so much information that it’s unwieldy. It needed to be inclusive, yet practical. As such, determinations needed to be made on whose holidays and observances were put on the calendar, and whose were not. With regards to people’s ancestry, groups that made up 0.85% of the New Jersey population (approximately 75,000 people) and higher, according to Census data, were chosen. Ultimately, the cut-off needed to be made somewhere, and while a round 1.0% seemed a good fit at first, there were too many ancestries with slightly less than that. 0.85% was significantly higher than any of the next population percentages, and so it made a satisfactory threshold. There are 20 ancestries with populations above 75,000, and in total they make up 58.6% of the New Jersey population. In terms of New Jersey’s religious landscape, the population is 67% Christian, 18% Unaffiliated (“Nones”), and 12% Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and Hindu. These six religious affiliations, which add up to 97% of the NJ population, were chosen for the calendar. 2% of the state is made up of other religions and faiths, but good data on those is lacking. -

List of 2014 China Public Ho 014 China Public Holidays Lic Holidays

List of 2014 China public holidays Day Date Holiday Comments Wednesday Jan-01 New Years Day Thursday Jan-30 Chinese New Year Eve Eve of 1st lunar month Friday Jan-31 Chinese New Year 1st day of 1st lunar month Saturday Feb-01 Chinese New Year 2nd day of 1st lunar month Sunday Feb-02 Chinese New Year 3rd day of 1st lunar month Monday Feb-03 Chinese New Year 4th day of 1st lunar month Tuesday Feb-04 Chinese New Year 5th day of 1st lunar month Qing Ming Jie, Tomb Sweeping Day or Saturday Apr-05 Ching Ming Festival Mourning Day Thursday May-01 Labour Day Friday May-02 Labour Day Monday Jun-02 Dragon Boat Festival Tuen Ng Festival Monday Sep-08 Mid Autumn Festival Moon Festival Wednesday Oct-01 National Day Double Ninth Festival or Dual-Yang Thursday Oct-02 Chung Yeung Festival Festival Thursday Oct-02 National Day Friday Oct-03 National Day List of 2014 Hong Kong public holidays Day Date Holiday Comments Wednesday Jan-01 New Years Day Friday Jan-31 Chinese New Year Chinese New Year' s Day Saturday Feb-01 Chinese New Year 2nd day of 1st lunar month Sunday Feb-02 Chinese New Year 3rd day of 1st lunar month Monday Feb-03 Chinese New Year 4th day of 1st lunar month Saturday Apr-05 Ching Ming Festival Tomb Sweeping Day or Mourning Day Friday Apr-18 Good Friday Catholic or protestant Monday Apr-21 Easter Monday Catholic or protestant Thursday May-01 Labour Day May Day TBC. 8th day of the 4th month in the Tuesday May-06 The Buddhas Birthday Chinese lunar calendar Monday Jun-02 Dragon Boat Festival Tuen Ng Festival Special Administration Tuesday Jul-01 -

January Report 2019 Contents

intelligence January Report 2019 Contents Tax Free Trends Summary 03 Tax Free Sales Trends 05 A Glance at Indian tourists' spending habits 06 Tax Free Sales by Destination and Source 07 Top 5 Visitor Nations per Destination Country 09 Currency Trends 11 Arrivals Forecast Europe Overview 13 France 14 United Kingdom 15 Italy 16 Spain 17 Germany 18 Austria 19 Finland 20 Portugal 21 Ireland 22 Czech Republic 23 Planet International Calendar 24 January Report 2019 Planet Intelligence | 2 Shopping & Arrivals Growth Summary - January 2019 Top 5 Destination Markets +1% Total Sales Tax Free Vouchers/ Avg. Transaction Arrival Sales Turnover Transaction Values (ATV) Numbers France +5% -3% +8% -5% United Kingdom -1% -8% +8% +2% Italy +6% +9% -3% 0% -2% Total Vouchers Spain -3% +14% -14% +7% Germany -11% -10% -2% -3% Top 5 Source Markets Tax Free Vouchers/ Avg. Transaction Arrival Sales Turnover Transaction Values (ATV) Numbers +3% Total ATV China +8% +1% +8% +32% USA +21% +7% +13% +6% Russia -22% -18% -5% -10% Taiwan +51% +4% +45% +21% +1% South Korea +6% +4% +2% -2% Total Arrivals January Report 2019 Planet Intelligence | 3 Shopping & Arrivals Growth Summary - YTD Top 5 Destination Markets +1% Total Sales Tax Free Vouchers/ Avg. Transaction Arrival Sales Turnover Transaction Values (ATV) Numbers France +5% -3% +8% -5% United Kingdom -1% -8% +8% +2% Italy +6% +9% -3% 0% -2% Total Vouchers Spain -3% +14% -14% +7% Germany -11% -10% -2% -3% Top 5 Source Markets Tax Free Vouchers/ Avg. Transaction Arrival Sales Turnover Transaction Values (ATV) Numbers +3% Total ATV China +8% +1% +8% +32% USA +21% +7% +13% +6% Russia -22% -18% -5% -10% Taiwan +51% +4% +45% +21% +1% South Korea +6% +4% +2% -2% Total Arrivals January Report 2019 Planet Intelligence | 4 Tax Free Shopping Sales Trends – January 2019 Overview Sterling hits two-month high The start of the year saw a modest lift in Tax Free shopping against euro and US dollar sales, increasing 1% year-on-year in January 2019. -

Chinese Holidays Quick Start Guide a Year of Family-Friendly Recipes, Activities & Crafts!

Chinese Holidays Quick Start Guide A Year of Family-Friendly Recipes, Activities & Crafts! ChineseAmericanFamily.com 2018 Chinese Holiday Calendar 1 12/30 – 1/1 NEW YEAR JAN China Public Holiday 16 2/15 - 2/21 • Clean the House CHINESE NEW YEAR • Cook Reunion Dinner FEB China Public Holiday • Give Red Envelopes 2 • Make Tang Yuan LANTERN FESTIVAL • Visit Lantern Displays MAR • Solve Lantern Riddles 5 4/5 - 4/7 • Sweep Family Graves QINGMING FESTIVAL • Spend Time Outdoors APR China Public Holiday • Fly Kites 1 4/29 - 5/1 LABOR DAY MAY China Public Holiday 18 6/16 - 6/18 • Make Zongzi DRAGON BOAT FESTIVAL • Attend Dragon Boat JUN China Public Holiday Races 17 • Go Stargazing QIXI FESTIVAL AUG • Plan a Date Night • 25 HUNGRY GHOST Burn Joss Paper • Attend Chinese Opera AUG FESTIVAL • Make Floating Lantern 24 9/22 - 9/24 • Gift Mooncakes MID-AUTUMN FESTIVAL • Make a Lantern SEP China Public Holiday • Eat Under Moonlight 1 10/1 - 10/7 NATIONAL DAY OCT China Public Holiday • Go for a Hike 17 • Visit Older Relatives DOUBLE NINTH FESTIVAL OCT • Drink Chrysanthemum Tea 21 • Make Tang Yuan DONGZHI FESTIVAL DEC • Eat Lamb Dumplings The Chinese Holidays Quick Start Guide Chinese New Year FEBRUARY 16, 2018 Chinese New Year, also referred to as Lunar New Year, is the most important holiday on the Chinese calendar. The holiday is actually a two week festival filled with reunions among family and friends, an abundance of delicious food and wishes for a new year filled with prosperity, joy and good fortune. Do Cook Gift Clean the Home Plan a Reunion Give Red Envelopes Dinner Visit ChineseAmericanFamily.com For More :: 3 The Chinese Holidays Quick Start Guide Lantern Festival MARCH 2, 2018 The Lantern Festival, also known as the Yuan Xiao Festival, welcomes the lunar year’s first full moon.