Cataleg-Fires.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valmontone Conference on Mattia Preti

Baroque Routes - 2014 / 15 5 Valmontone Conference on Mattia Preti A scholarly conference focused on the Cavaliere Calabrese, the artist Mattia Preti, was held on Monday 3 November 2014 at Palazzo Pamphilj in Valmontone, around 30 kilometres from Rome. Participants examined the status of research into this artist following the celebrations of the 400th centenary of his birth (1613-2013). The event was titled ‘Sotto la volta dell’aria. Mattia Preti: Approfondimenti e ricerche.’ This conference was organised by the International Institute for Baroque Studies at the University of Malta in association with the Soprintendenza PSAE del Lazio and the Comune di Valmontone. For this purpose an on-site scientific committee composed of Sante Guido, Dora Catalano of the Superintendence extensive decoration of eighteenth-century of the region, Monica Di Gregorio, director palaces throughout Europe. Allegorical figures of the museum of Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, representing the natural elements, such as Day, and Giuseppe Mantella, a leading restorer of Night, Dawn, as well as Love, Fortune and many Mattia’s Preti’s works, was set up. The ‘Volta others, adorn this vault. It is important to note dell’aria’ indicated in the title of the conference that it was during his stay at Valmontone, that refers to a fresco on the ceiling of the grand Preti planned his entire project for the decoration hall of the palace where the event took place, of the Co-cathedral in Valletta. When he arrived and which was painted in the spring of 1661 in Malta in the summer of 1661 and proposed to for Prince Camillo Pamphilj in the piano paint the story of St John the Baptist, his designs nobile of his palace. -

Flemish Masters. and Others Artists

- S ArtiSts WWI ' Masters. and others FlemiSh QA ts froth the' Heritage Fondo Edifici di Cuito 7 mksWO N, "A Irm.."P A^kh I el Wi d-81'inLer HIM S Re way S - - 5 - - ---i gq abln S S 5-- 711 Ms 'v 7q'Vox q Oil S S "Yom twit no, eel ANN S - S -- ON-sios N'111_1 AFT Coo MEW, Z ltvll it ME Am WEEK-5 Zf -. S Too I A I Uzi 111P PRO a 9 P5001"" "S 0, if I (/f t)pi 'lei on (111_^i Tv TWO 1W I r 1111 CA ff j i I I A D 0 IIII - A" j awl M ":jQ!7VW 1 Olt, A op - ma n. 0 / r A A A -: A WA 5/ A A A5 A A 5/ a RAT A / ANO C /AA 4 1 non lj A A •, ,- A ,, oil At A Wy * : ,- low As A -, '1 - I. ME QC Ai 1_1 Al -• '1' A*; At A' Mum A 1 14 . A A -.? 4 / - 5/ - A Am A CAI soy I4 AW ( A A q I!' A , Av Saw to mom Sf aw US all lk OUR ;iP mom 0 Sm TAM AS NMI - - PALAllO ME RUSPOLI FONDAZIONE MEMMO MINIsTER0 DELL'INTERNO DIPARTTh/IENTO PER LE LIBERTA CIVILI E L'IMMIGRAZIONE FLEMISH MASTERS AND OTHERS ARTISTS Foreign Artists from the Heritage of the Fondo Edifici di Culto del Ministero dell'Interno <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER Under the High Patronage of the President of Italy Giorgio Napolitano FLEMISH MASTERS AND OTHERS ARTISTS FOREIGN ARTISTS FROM THE HERITAGE OF THE FONDO EDIFICI DI CULTO DEL MINISTERO DELL'INTERNO Rome - Palazzo Ruspoli 1 July - 10 September 2008 MINISTERO FONDAZIONE COMITATO TECNICO Exhibition designer DELL'INTERNO MEMMO Giuseppe Mario Scalia Rosalia Lilly D'Amico Dipartimento per le liberta Cape dell'Ufficio Pian/icazione eAffari Generali della civili e l'immigrazione Direzione Centrale per l'Amministrazione Graphic design del Fonda Ed/Ici -

006-San Marco

(006/41) Basilica di San Marco Evangelista al Campidoglio San Marco is a 9th century minor basilica and parish and titular church, on ancient foundations, located on Piazza Venezia. The dedication is to St Mark the Evangelist, patron saint of Venice, and it is the the church for Venetian expatriates at Rome. The full official name is San Marco Evangelista al Campidoglio, "St Mark the Evangelist at the Capitol". History The basilica was probably founded by Pope St. Marcus (Mark) in 336 over an older oratory, and is one of Rome's oldest churches. It stands on the site where St Marcus is said to have lived, and was known as the Titulus Pallacinae. The church is thus recorded as Titulus Marci in the 499 synod of Pope Symmachus. [1] The church was modified in the 5th century, and was left facing the opposite direction. It seems from the archaeology that the basilica had a serious fire in the same century or the next, as burnt debris was found in the stratigraphy. [1] It was reconstructed in the 8th century by Pope Adrian I (772-795). It was flooded when the Tiber rose above its banks soon after, in 791. Pope Gregory IV (827-844) was responsible for what is now considered to have been a (006/41) complete rebuilding. The orientation of the church was reversed, with the old apse being demolished and replaced by a main entrance. The old entrance was replaced by a new apse, with a mosaic in the conch which survives. However, the three windows which the apse had were later blocked. -

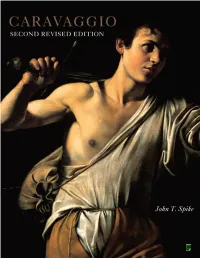

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio. -

Space in the Baroque Roman Architecture

SPACE IN THE BAROQUE ROMAN ARCHITECTURE TOMASZ DZIUBECKI The architecture in Rome in the 17 th century is utmost part of the picture could be located: as on the usually described as baroque par excellence – as preparatory drawing for the Adoration of the Magi a sample for many early modern European archi- (ca. 1481, Gabinetto dei Disegni e Stampe, Uf [ zi) tects. Furthermore the style of buildings erected in (Fig. 1). An example of the architecture, where that Rome was used to be described as overdecorated kind of space perception can bee seen is the way with fantasy both in plans and ornamentation. But Donato Bramante created the presbitery in S. Maria the analysies of some scholars like Rudolf Wit- presso S. Satiro in Milan (1485) so the space illu- tkower and Jan Bia ostocki enabled to describe the sion was convincing and clear in its every part – it baroque style with a greater precision (what also was not the issue of an „optical game” but of lack made possible to see positive values of architecture of space behind the wall because of the street there outside the Italian centres). 1 It is dif [ cult to limit the (Fig. 2). character of art created in the Eternal City to a one In the art of manierism the construction of space group of features – if a conception of style still has was of no interest: for example Pontormo painting a descriptive value. 2 Nevertheless our attention is the Entombment for the Capponi Chapel in S. Felic- attracted by a speci [ c attitude towards the concept ita in Florence (in 1525–1528), crowded all the [ g- of space by the 17 th century Roman architects. -

098-San Carlo Al Corso

(098/8) San Carlo al Corso San Carlo al Corso (formally Santi Ambrogio e Carlo al Corso) is a 17th century minor basilica, a titular and conventual church at Via del Corso in the rione Campo Marzio. The dedication is jointly to St Ambrose and St Charles Borromeo, who are the most famous of the bishops of Milan. [1] It used to be the national church of the Duchy of Milan, but since the unification of Italy has been the regional church of Lombardy. It also contains the Chapel of St Olav, which is the national shrine in Rome for expatriates and pilgrims from Norway. [1] History The first church on the site was called San Niccolò del Tufo. The dedication was to St Nicholas of Myra. The first unambiguous reference is in a document in the archives of San Silvestro dated 1269, and the church is listed in the late mediaeval catalogues. [1] It was granted to the Lombard community by Pope Sixtus IV, after he had approved of the establishment of a Lombard Confraternity in 1471. They rededicated it to their patron St Ambrose, and restored the church. The work, which probably amounted to a rebuilding, was finished in 1520 after seven years' effort. It is on record that Baldassare Peruzzi and Perino del Vaga executed frescoes here. [1] In 1610 St Charles Borromeo was canonized, and it was this event that inspired the building of a much larger church just to the north of the old one. The result is the present edifice. The confraternity, now named the Archconfraternity of Saints Ambrose and Charles of the Lombard Nation, undertook to fund the project and obtained an initial donation from Milanese Cardinal Luigi Alessandro Omodei the Elder which enabled work to begin. -

Italian Master Drawings from the Wolfgang Ratjen Collection, 1525-1835 May 8, 2011 - November 27, 2011

Updated Friday, April 22, 2011 | 1:25:45 PM Last updated Friday, April 22, 2011 Updated Friday, April 22, 2011 | 1:25:45 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Italian Master Drawings from the Wolfgang Ratjen Collection, 1525-1835 May 8, 2011 - November 27, 2011 Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. To obtain images and permissions for print or digital reproduction please provide your name, press affiliation and all other information as required(*) utilizing the order form at the end of this page. Digital images will be sent via e-mail. Please include a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned and your phone number so that we may contact you. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. Cat. No. 1 / File Name: 3253-103.jpg Title Title Section Raw Cat. No. 1 / File Name: 3253-103.jpg Giulio Romano Giulio Romano The Four Elements, c. 1530 Display Order The Four Elements, c. 1530 pen and brown ink with brown wash pen and brown ink with brown wash 242 x 337 mm Title Assembly The Four Elements 242 x 337 mm National Gallery of Art, Washington, Wolfgang Ratjen Collection, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 2007 Title Prefix National Gallery of Art, Washington, Wolfgang Ratjen Collection, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 2007 Title Title Suffix Cat. -

The Landscapes of Gaspard Dughet: Artistic Identity and Intellectual Formation in Seventeenth-Century Rome

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE LANDSCAPES OF GASPARD DUGHET: ARTISTIC IDENTITY AND INTELLECTUAL FORMATION IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ROME Sarah Beth Cantor, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Professor Anthony Colantuono, Department of Art History and Archaeology The paintings of Gaspard Dughet (1615-1675), an artist whose work evokes the countryside around Rome, profoundly affected the representation of landscape until the early twentieth century. Despite his impact on the development of landscape painting, Dughet is recognized today as the brother-in-law of Nicolas Poussin rather than for his own contribution to the history of art. His paintings are generally classified as decorative works without subjects that embody no higher intellectual pursuits. This dissertation proposes that Dughet did, in fact, represent complex ideals and literary concepts within his paintings, engaging with the pastoral genre, ideas on spirituality expressed through landscape, and the examination of ancient Roman art. My study considers Dughet’s work in the context of seventeenth-century literature and antiquarian culture through a new reading of his paintings. I locate his work within the expanding discourse on the rhetorical nature of seventeenth-century art, exploring questions on the meaning and interpretation of landscape imagery in Rome. For artists and patrons in Italy, landscape painting was tied to notions of cultural identity and history, particularly for elite Roman families. Through a comprehensive examination of Dughet’s paintings and frescoes commissioned by noble families, this dissertation reveals the motivations and intentions of both the artist and his patrons. The dissertation addresses the correlation between Dughet’s paintings and the concept of the pastoral, the literary genre that began in ancient Greece and Rome and which became widely popular in the early seventeenth century. -

The Chigi Palace in Ariccia Illustrated Guide

The Chigi Palace in Ariccia Illustrated guide The Chigi Palace in Ariccia THE CHIGI PALACE IN ARICCIA Illustrated guide Photography Edited by City of Ariccia Mauro Aspri (Ariccia) Daniele Petrucci Arte Fotografica (Roma) Roberto Di Felice Mauro Coen (Roma) Francesco Petrucci Mayor Augusto Naldoni (Roma) Claudio Fortini Daniele Petrucci 1st Area Director Burial Ground of II Partic Legion (Empereor Septimius Severus) Francesco Petrucci Chigi’s Palace curator Noble Floor Princess Antonietta Green room Bedroom Fountains 17th c. Nun’s room Studio of Albani Service Prince Mario room room Sayn Park Avenue Chapel Wittgenstein Aviary (Cappella) Summer dining Bedroom hall (Camera Rosa) (Uccelliera) Ariosto room Gallery Red and yellow hall Master Hall Landscape Tr ucco room Borghese room Mario de’ Fiori Beauties gallery room room Ruins of Fountains S. Roch 17th c. Grotesque room Pharmacy Neviera Monument of Pandusa (Piazzale Mascherone) 1st c. Ground Floor Square of the mask Ancient Quarry Pump House Chapel Garden of the fallen Peschiera Large Square Room of Room of Room of the Chinese Arquebus Big Flocked Paper wallpaper Kitchen (Cucinone) Public gardens Monumental Bridge of Ariccia Chigi Palace 19th c. Gemini room Piazza di Corte Dog’s hall (Bernini, 1662-65) Leo Virgo Antechamber e Cancer room room room The Chigi Palace in Ariccia Piazza di Corte 14 -00072 Ariccia (Roma) ph. +39 069330053 - fax +39 069330988 - Red bedroom www.palazzochigiariccia.com - [email protected] Publisher Arti Grafiche Ariccia Ariccia - printed in october 2019 View of the Chigi Palace on the Piazza di Corte by Bernini. The Ducal Palace of Ariccia represents an unique example of Roman Baroque residence unaltered in its own context and original furnishings, documenting the splendour of one of the major Italian papal families, once owners of the Chigi Palace in Rome, nowadays seat of the Presidency of the Council of Ministries. -

Material Bernini

Material Bernini Edited by Evonne Levy and Carolina Mangone Routledge R Taylor & Francis Croup LONDON AND NEW YORK Contents List of Illustrations vii Contributors xHi Preface xvii Acknowledgments xxi Abbreviations xxiii Obstacles in the Path to a Material Bernini (1900-Present) 1 Evonne Levy PART I: IMMATERIAL/MATERIAL The Matter of Metaphor: Truth, Sculpture, and the Word 23 Maarten Delbeke Im/material Bernini 39 Fabio Barry Bernini scultore pittoresco 69 Carolina Mangone Body and Clay: Material Agency from an Early Modern Perspective 105 Joris van Gastel PART II: CLAY BOZZETTI What Is a Bozzetto? 123 Michael Cole Bernini's Bozzetti and the Trope of Fire 147 Steven F. Ostrozv The Concept of Bernini's "Calculated Spontaneity" A Critical Reassessment 169 Tara L. Nadeau vi MATERIAL BERNINI Bernini/Not Bernini: Reflections on the Role of Technical Evidence in the Attribution of Bernini's Terracottas 187 CD. Dickerson III and Anthony Sigel Bibliography 219 Index 239 Illustrations Cover image: Gianlorenzo Bernini, 3.4 Gianlorenzo Bernini and Cathedra Petri, detail, 1647-53, gilt bronze, Guillaume Courtois, apse with St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican. (Photo: © Martyrdom of St. Andrew, 1668, Alessandro Vasari) S. Andrea al Quirinale, Rome. (Photo: Fabio Barry) The Matter of Metaphor: Truth, 3.5 Gianlorenzo Bernini, lateral portal Sculpture, and the Word of Cornaro Chapel, 1647-52, S. Maria della Rome. Fabio 2.1 Gianlorenzo Bernini, Truth, 1645, Vittoria, (Photo: marble, Galleria Borghese, Rome. Barry) of (Photo: Scala, Florence—courtesy 3.6 Gianlorenzo Bernini, back wall of le Attivita the Ministero per i Beni e Cornaro Chapel, 1647-52, S. Maria della Culturali) Vittoria, Rome. -

Caravaggio's Other 'Judith and Holofernes'

1 Caravaggio’s other ‘Judith and Holofernes’ By John Gash The discovery in 2014 in a house in Toulouse of a painting of Judith beheading Holofernes in the style of Caravaggio [Fig. 1, plus Figs. 1a, b & c] has unleashed a groundswell of academic and popular interest and divided scholarly opinion - so much so that the French state placed a three-year export embargo on it, which expired on 16 November 2018, in order to further assess the problem. While some consider it an original by Caravaggio, the only positive counter-suggestion has been to identify it as a work of the Flemish artist, Louis Finson (before 1580-1617), resident in Naples at the time of Caravaggio’s first and second visits there, in 1606-07 and 1609-10. Alternatively, those who are not fully satisfied with the idea of Caravaggio’s authorship, have wondered whether it might be a very good copy of a lost work or, more intriguingly, an original Caravaggio that was either finished, or slightly altered, by another hand. To these one might add the possibility of a partial collaboration, for although Caravaggio is conventionally considered to have painted alone, without assistants, we now know that Cecco del Caravaggio (Francesco Buoneri) at least was a studio assistant of his in Rome in 1605 (and perhaps beyond), albeit as a teenager, while no less an authority than Walter Friedlaender felt that the Madonna of the Rosary in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, probably painted, or at least finished, in Naples in 1606- 07, betrayed the evidence of collaborators.1 More recently, John Spike has argued that the 1 Maurizio Marini: ‘Un estrema residenza e un ignoto aiuto del Caravaggio in Roma’, Antologia di Belle Arti, 19- 20, pp.176-180. -

FB Catalogue Final.Pdf

Seattle, Seattle Art Museum Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum October 17 2019 - January 26 2020 March 01 2020 - June 14 2020 Curated by Sylvain Bellenger with the collaboration of Chiyo Ishikawa, George Shackleford and Guillaume Kientz Embassy of Italy Washington The Embassy of Italy in Washington D.C. Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte Seattle Art Museum Director Illsley Ball Nordstrom Director and CEO Front cover Sylvain Bellenger Amada Cruz Parmigianino Lucretia Chief Curator Susan Brotman Deputy Director for Art and 1540, Oil on panel Linda Martino Curator of European Painting and Sculpture Naples, Museo e Real Bosco Chiyo Ishikawa di Capodimonte Exhibition Department Patrizia Piscitello Curatorial Intern Exhibition Catalogue Giovanna Bile Gloria de Liberali Authors Documentation Department Deputy Director for Art Administration Sylvain Bellenger Alessandra Rullo Zora Foy James P. Anno Christopher Bakke Head of Digitalization Exhibitions and Publications Manager Proofreading and copyediting Carmine Romano Tina Lee Mark Castro Graphic Design Restoration Department Director of Museum Services Studio Polpo Alessandra Golia and Chief Registrar Lauren Mellon Photos credits Legal Consulting Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte Studio Luigi Rispoli Associate Registrar for Exhibitions © Alberto Burri by SIAE 2019, Fig. 5 Megan Peterson © 2019 Andy Warhol Foundation American Friends of Capodimonte President for the Visual Arts by SIAE, Fig. 6 Nancy Vespoli Director of Design and Installation Photographers Nathan Peek and his team Luciano Romano Speranza Digital Studio, Napoli Exhibition Designer Paul Martinez Published by MondoMostre Printed in Italy by Tecnostampa Acting Director of Communications Finished printing on September 2019 Cindy McKinley and her team Copyright © 2019 MondoMostre Chief Development Ofcer Chris Landman and his team All Rights Reserved.