Space in the Baroque Roman Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valmontone Conference on Mattia Preti

Baroque Routes - 2014 / 15 5 Valmontone Conference on Mattia Preti A scholarly conference focused on the Cavaliere Calabrese, the artist Mattia Preti, was held on Monday 3 November 2014 at Palazzo Pamphilj in Valmontone, around 30 kilometres from Rome. Participants examined the status of research into this artist following the celebrations of the 400th centenary of his birth (1613-2013). The event was titled ‘Sotto la volta dell’aria. Mattia Preti: Approfondimenti e ricerche.’ This conference was organised by the International Institute for Baroque Studies at the University of Malta in association with the Soprintendenza PSAE del Lazio and the Comune di Valmontone. For this purpose an on-site scientific committee composed of Sante Guido, Dora Catalano of the Superintendence extensive decoration of eighteenth-century of the region, Monica Di Gregorio, director palaces throughout Europe. Allegorical figures of the museum of Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, representing the natural elements, such as Day, and Giuseppe Mantella, a leading restorer of Night, Dawn, as well as Love, Fortune and many Mattia’s Preti’s works, was set up. The ‘Volta others, adorn this vault. It is important to note dell’aria’ indicated in the title of the conference that it was during his stay at Valmontone, that refers to a fresco on the ceiling of the grand Preti planned his entire project for the decoration hall of the palace where the event took place, of the Co-cathedral in Valletta. When he arrived and which was painted in the spring of 1661 in Malta in the summer of 1661 and proposed to for Prince Camillo Pamphilj in the piano paint the story of St John the Baptist, his designs nobile of his palace. -

Flemish Masters. and Others Artists

- S ArtiSts WWI ' Masters. and others FlemiSh QA ts froth the' Heritage Fondo Edifici di Cuito 7 mksWO N, "A Irm.."P A^kh I el Wi d-81'inLer HIM S Re way S - - 5 - - ---i gq abln S S 5-- 711 Ms 'v 7q'Vox q Oil S S "Yom twit no, eel ANN S - S -- ON-sios N'111_1 AFT Coo MEW, Z ltvll it ME Am WEEK-5 Zf -. S Too I A I Uzi 111P PRO a 9 P5001"" "S 0, if I (/f t)pi 'lei on (111_^i Tv TWO 1W I r 1111 CA ff j i I I A D 0 IIII - A" j awl M ":jQ!7VW 1 Olt, A op - ma n. 0 / r A A A -: A WA 5/ A A A5 A A 5/ a RAT A / ANO C /AA 4 1 non lj A A •, ,- A ,, oil At A Wy * : ,- low As A -, '1 - I. ME QC Ai 1_1 Al -• '1' A*; At A' Mum A 1 14 . A A -.? 4 / - 5/ - A Am A CAI soy I4 AW ( A A q I!' A , Av Saw to mom Sf aw US all lk OUR ;iP mom 0 Sm TAM AS NMI - - PALAllO ME RUSPOLI FONDAZIONE MEMMO MINIsTER0 DELL'INTERNO DIPARTTh/IENTO PER LE LIBERTA CIVILI E L'IMMIGRAZIONE FLEMISH MASTERS AND OTHERS ARTISTS Foreign Artists from the Heritage of the Fondo Edifici di Culto del Ministero dell'Interno <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER Under the High Patronage of the President of Italy Giorgio Napolitano FLEMISH MASTERS AND OTHERS ARTISTS FOREIGN ARTISTS FROM THE HERITAGE OF THE FONDO EDIFICI DI CULTO DEL MINISTERO DELL'INTERNO Rome - Palazzo Ruspoli 1 July - 10 September 2008 MINISTERO FONDAZIONE COMITATO TECNICO Exhibition designer DELL'INTERNO MEMMO Giuseppe Mario Scalia Rosalia Lilly D'Amico Dipartimento per le liberta Cape dell'Ufficio Pian/icazione eAffari Generali della civili e l'immigrazione Direzione Centrale per l'Amministrazione Graphic design del Fonda Ed/Ici -

006-San Marco

(006/41) Basilica di San Marco Evangelista al Campidoglio San Marco is a 9th century minor basilica and parish and titular church, on ancient foundations, located on Piazza Venezia. The dedication is to St Mark the Evangelist, patron saint of Venice, and it is the the church for Venetian expatriates at Rome. The full official name is San Marco Evangelista al Campidoglio, "St Mark the Evangelist at the Capitol". History The basilica was probably founded by Pope St. Marcus (Mark) in 336 over an older oratory, and is one of Rome's oldest churches. It stands on the site where St Marcus is said to have lived, and was known as the Titulus Pallacinae. The church is thus recorded as Titulus Marci in the 499 synod of Pope Symmachus. [1] The church was modified in the 5th century, and was left facing the opposite direction. It seems from the archaeology that the basilica had a serious fire in the same century or the next, as burnt debris was found in the stratigraphy. [1] It was reconstructed in the 8th century by Pope Adrian I (772-795). It was flooded when the Tiber rose above its banks soon after, in 791. Pope Gregory IV (827-844) was responsible for what is now considered to have been a (006/41) complete rebuilding. The orientation of the church was reversed, with the old apse being demolished and replaced by a main entrance. The old entrance was replaced by a new apse, with a mosaic in the conch which survives. However, the three windows which the apse had were later blocked. -

098-San Carlo Al Corso

(098/8) San Carlo al Corso San Carlo al Corso (formally Santi Ambrogio e Carlo al Corso) is a 17th century minor basilica, a titular and conventual church at Via del Corso in the rione Campo Marzio. The dedication is jointly to St Ambrose and St Charles Borromeo, who are the most famous of the bishops of Milan. [1] It used to be the national church of the Duchy of Milan, but since the unification of Italy has been the regional church of Lombardy. It also contains the Chapel of St Olav, which is the national shrine in Rome for expatriates and pilgrims from Norway. [1] History The first church on the site was called San Niccolò del Tufo. The dedication was to St Nicholas of Myra. The first unambiguous reference is in a document in the archives of San Silvestro dated 1269, and the church is listed in the late mediaeval catalogues. [1] It was granted to the Lombard community by Pope Sixtus IV, after he had approved of the establishment of a Lombard Confraternity in 1471. They rededicated it to their patron St Ambrose, and restored the church. The work, which probably amounted to a rebuilding, was finished in 1520 after seven years' effort. It is on record that Baldassare Peruzzi and Perino del Vaga executed frescoes here. [1] In 1610 St Charles Borromeo was canonized, and it was this event that inspired the building of a much larger church just to the north of the old one. The result is the present edifice. The confraternity, now named the Archconfraternity of Saints Ambrose and Charles of the Lombard Nation, undertook to fund the project and obtained an initial donation from Milanese Cardinal Luigi Alessandro Omodei the Elder which enabled work to begin. -

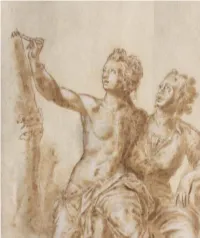

Italian Master Drawings from the Wolfgang Ratjen Collection, 1525-1835 May 8, 2011 - November 27, 2011

Updated Friday, April 22, 2011 | 1:25:45 PM Last updated Friday, April 22, 2011 Updated Friday, April 22, 2011 | 1:25:45 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Italian Master Drawings from the Wolfgang Ratjen Collection, 1525-1835 May 8, 2011 - November 27, 2011 Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. To obtain images and permissions for print or digital reproduction please provide your name, press affiliation and all other information as required(*) utilizing the order form at the end of this page. Digital images will be sent via e-mail. Please include a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned and your phone number so that we may contact you. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. Cat. No. 1 / File Name: 3253-103.jpg Title Title Section Raw Cat. No. 1 / File Name: 3253-103.jpg Giulio Romano Giulio Romano The Four Elements, c. 1530 Display Order The Four Elements, c. 1530 pen and brown ink with brown wash pen and brown ink with brown wash 242 x 337 mm Title Assembly The Four Elements 242 x 337 mm National Gallery of Art, Washington, Wolfgang Ratjen Collection, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 2007 Title Prefix National Gallery of Art, Washington, Wolfgang Ratjen Collection, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 2007 Title Title Suffix Cat. -

The Landscapes of Gaspard Dughet: Artistic Identity and Intellectual Formation in Seventeenth-Century Rome

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE LANDSCAPES OF GASPARD DUGHET: ARTISTIC IDENTITY AND INTELLECTUAL FORMATION IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ROME Sarah Beth Cantor, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Professor Anthony Colantuono, Department of Art History and Archaeology The paintings of Gaspard Dughet (1615-1675), an artist whose work evokes the countryside around Rome, profoundly affected the representation of landscape until the early twentieth century. Despite his impact on the development of landscape painting, Dughet is recognized today as the brother-in-law of Nicolas Poussin rather than for his own contribution to the history of art. His paintings are generally classified as decorative works without subjects that embody no higher intellectual pursuits. This dissertation proposes that Dughet did, in fact, represent complex ideals and literary concepts within his paintings, engaging with the pastoral genre, ideas on spirituality expressed through landscape, and the examination of ancient Roman art. My study considers Dughet’s work in the context of seventeenth-century literature and antiquarian culture through a new reading of his paintings. I locate his work within the expanding discourse on the rhetorical nature of seventeenth-century art, exploring questions on the meaning and interpretation of landscape imagery in Rome. For artists and patrons in Italy, landscape painting was tied to notions of cultural identity and history, particularly for elite Roman families. Through a comprehensive examination of Dughet’s paintings and frescoes commissioned by noble families, this dissertation reveals the motivations and intentions of both the artist and his patrons. The dissertation addresses the correlation between Dughet’s paintings and the concept of the pastoral, the literary genre that began in ancient Greece and Rome and which became widely popular in the early seventeenth century. -

The Chigi Palace in Ariccia Illustrated Guide

The Chigi Palace in Ariccia Illustrated guide The Chigi Palace in Ariccia THE CHIGI PALACE IN ARICCIA Illustrated guide Photography Edited by City of Ariccia Mauro Aspri (Ariccia) Daniele Petrucci Arte Fotografica (Roma) Roberto Di Felice Mauro Coen (Roma) Francesco Petrucci Mayor Augusto Naldoni (Roma) Claudio Fortini Daniele Petrucci 1st Area Director Burial Ground of II Partic Legion (Empereor Septimius Severus) Francesco Petrucci Chigi’s Palace curator Noble Floor Princess Antonietta Green room Bedroom Fountains 17th c. Nun’s room Studio of Albani Service Prince Mario room room Sayn Park Avenue Chapel Wittgenstein Aviary (Cappella) Summer dining Bedroom hall (Camera Rosa) (Uccelliera) Ariosto room Gallery Red and yellow hall Master Hall Landscape Tr ucco room Borghese room Mario de’ Fiori Beauties gallery room room Ruins of Fountains S. Roch 17th c. Grotesque room Pharmacy Neviera Monument of Pandusa (Piazzale Mascherone) 1st c. Ground Floor Square of the mask Ancient Quarry Pump House Chapel Garden of the fallen Peschiera Large Square Room of Room of Room of the Chinese Arquebus Big Flocked Paper wallpaper Kitchen (Cucinone) Public gardens Monumental Bridge of Ariccia Chigi Palace 19th c. Gemini room Piazza di Corte Dog’s hall (Bernini, 1662-65) Leo Virgo Antechamber e Cancer room room room The Chigi Palace in Ariccia Piazza di Corte 14 -00072 Ariccia (Roma) ph. +39 069330053 - fax +39 069330988 - Red bedroom www.palazzochigiariccia.com - [email protected] Publisher Arti Grafiche Ariccia Ariccia - printed in october 2019 View of the Chigi Palace on the Piazza di Corte by Bernini. The Ducal Palace of Ariccia represents an unique example of Roman Baroque residence unaltered in its own context and original furnishings, documenting the splendour of one of the major Italian papal families, once owners of the Chigi Palace in Rome, nowadays seat of the Presidency of the Council of Ministries. -

Material Bernini

Material Bernini Edited by Evonne Levy and Carolina Mangone Routledge R Taylor & Francis Croup LONDON AND NEW YORK Contents List of Illustrations vii Contributors xHi Preface xvii Acknowledgments xxi Abbreviations xxiii Obstacles in the Path to a Material Bernini (1900-Present) 1 Evonne Levy PART I: IMMATERIAL/MATERIAL The Matter of Metaphor: Truth, Sculpture, and the Word 23 Maarten Delbeke Im/material Bernini 39 Fabio Barry Bernini scultore pittoresco 69 Carolina Mangone Body and Clay: Material Agency from an Early Modern Perspective 105 Joris van Gastel PART II: CLAY BOZZETTI What Is a Bozzetto? 123 Michael Cole Bernini's Bozzetti and the Trope of Fire 147 Steven F. Ostrozv The Concept of Bernini's "Calculated Spontaneity" A Critical Reassessment 169 Tara L. Nadeau vi MATERIAL BERNINI Bernini/Not Bernini: Reflections on the Role of Technical Evidence in the Attribution of Bernini's Terracottas 187 CD. Dickerson III and Anthony Sigel Bibliography 219 Index 239 Illustrations Cover image: Gianlorenzo Bernini, 3.4 Gianlorenzo Bernini and Cathedra Petri, detail, 1647-53, gilt bronze, Guillaume Courtois, apse with St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican. (Photo: © Martyrdom of St. Andrew, 1668, Alessandro Vasari) S. Andrea al Quirinale, Rome. (Photo: Fabio Barry) The Matter of Metaphor: Truth, 3.5 Gianlorenzo Bernini, lateral portal Sculpture, and the Word of Cornaro Chapel, 1647-52, S. Maria della Rome. Fabio 2.1 Gianlorenzo Bernini, Truth, 1645, Vittoria, (Photo: marble, Galleria Borghese, Rome. Barry) of (Photo: Scala, Florence—courtesy 3.6 Gianlorenzo Bernini, back wall of le Attivita the Ministero per i Beni e Cornaro Chapel, 1647-52, S. Maria della Culturali) Vittoria, Rome. -

1- Collecting Seventeenth-Century Dutch Painting in England 1689

-1- COLLECTING SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY DUTCH PAINTING IN ENGLAND 1689 - 1760 ANNE MEADOWS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy t University College London, November, 1988. -2- ABSTIACT This thesis examines the collecting of seventeenth century Dutch painting in England from 1689 marking the beginning of auction sales in England to 1760, Just prior to the beginning of the Royal Academy and the rising patronage for British art. An examination of the composition of English collections centred around the period 1694 when William end Mary passed a law permitting paintings to be imported for public sale for the first time in the history of collecting. Before this date paintings were only permitted entry into English ports for private use and enjoyment. The analysis of sales catalogues examined the periods before and after the 1694 change in the law to determine how political circumstances such as Continental wars and changes in fiscal policy affected the composition of collecting paintings with particular reference to the propensity for acquiring seventeenth century Dutch painting in England Chapter Two examines the notion that paintings were Imported for public sale before 1694, and argues that there had been essentially no change In the law. It considered also Charles It's seizure of the City's Charters relaxing laws protecting freemen of the Guilds from outside competition, and the growth of entrepreneur- auctioneers against the declining power of the Outroper, the official auctioneer elected by the Corporation of City of London. An investigation into the Poll Tax concluded that the boom in auction sales was part of the highly speculative activity which attended Parliament's need to borrow public funds to continue the war with France. -

Cataleg-Fires.Pdf

PUBLISHED BY We would like to thank the following for their professional help: Artur Ramon Art Nous tenons à remercier les professionnels suivants pour leur collaboration : Palla, 25. 08002 Barcelona Queremos agradecer la colaboración de los siguientes profesionales: PHOTOGRAPHS Christophe Defrance, Bénédicte de Donker, Viviana Farina, Guillem Fernández, Anna Gabrielli, Guillem F.H. Arianne Garaizabal, Yann le LanLemaître, Pilar Lorte, Manuela Mena Marqués, Benito Navarrete Prieto, Montserrat Pérez, Pere and Horacio Pérez-Hita, Dr Andrew Robinson, Jaume Sanahuja TRANSLATIONS and the entire team at ARTUR RAMON ART. Montserrat Pérez Traductorum GRAPHIC DESIGN Jaume Sanahuja PRINTING AND PHOTOMECHANICAL PROCESSING Gràfiques Ortell S.L. ISBN Member of TEFAF TEFAF MAASTRICHT WORKS ON PAPER 13 – 22 March 2015 Stand 704 SALON DU DESSIN 25 – 30 mars 2015 Paris. Palais Brongniart – Place de la Bourse Stand 29 Seriousness and passion for drawing: from the Raíz del arte to the international fairs I came to drawing through visual education, surrounded by works on paper in the family collec- tion. Then, in my training days, I was initiated into engraving, particularly the work of Giovanni Battista Piranesi. I discovered it through some books my father bought when I started work and delved more deeply into it in the late 80s in London, thanks to Professor John Wilton-Ely. Back in Barcelona, I devoted a number of monographic exhibitions to the Venetian master and through him I returned to drawing, because in it the artists’ first voice, their most intimate and honest part, can be heard. The passion for drawing led me to an outlandish venture for a country like mine, in which there is hardly any tradition of collecting works of this kind: a series of exhibitions under the title Raíz del arte (Root of Art)—to paraphrase Michelangelo, who thus defined drawing—, which brought together works by Spanish and Italian artists. -

Inaugurazione Restauri Della Sala Del Principe

Il Salone del PrIncIPe nel Palazzo dorIa PamPhIlj dI Valmontone Un ponte tra il Quirinale e Valmontone “meSe della cUltUra PamPhIlIa” dal 3 al 30 novembre 2014 Il Salone del PrIncIPe nel Palazzo dorIa PamPhIlj dI Valmontone Inaugurazione dei restauri - 28 novembre 2014 cItta’ dI Valmontone COMITATO D’ONORE COMITATO PROMOTORE COMITATO SCIENTIFICO Francesca Barracciu anna Imponente anna Imponente, Presidente Sottosegretario per i Beni Soprintendente per i Beni Storici Artistici dora catalano e le Attività Culturali e del Turismo ed Etnoantropologici del Lazio Francesco colalucci Vanessa Frazier alberto latini Ambasciatrice della Repubblica Sindaco della Città di Valmontone monica di Gregorio di Malta In Italia eleonora mattia Sante Guido Guido Fabiani Vice Sindaco della Città di Valmontone Giorgio leone Assessore Sviluppo Economico e Attività con delega alle Politiche Culturali e Sociali Giuseppe mantella Produttive Regione Lazio colombo Bastianelli daniele leodori Priore Conaternita del SS. Sacramento Presidente Consiglio Regionale del Lazio e Santo Rosario di San Martino al Cimino louis Godart Gianluca Petrassi Consigliere per la Conservazione del Dirigente Settore I, Città di Valmontone Patrimonio Artistico Palazzo del Quirinale Gianfranco trionfera Direttore "Valmontone Hospital" l’iniziativa Mese della Cultura Pamphilia è ideata e coordinata da eleonora mattia e anna Imponente con il contributo di SEGRETERIA TECNICA ORGANIZZATIVA RESTAURI FOTOGRAFIE monica di Gregorio Il restauro dei dipinti murali è stato realizzato da: archivio Soprintendenza massimiliano lucci masterpiece s.r.l. di antonella docci e Sergio Salvati per i Beni Storici artistici norma tomasi s.r.l. (I lotto) ed etnoantropologici del lazio tecnireco s.r.l. e roberto civetta (II lotto) Foto: marcello Fedeli, UFFICIO STAMPA rUP: rossella Vodret e anna Imponente Pasqualino rizzi marco leone, antonella d’ambrosio, direzione lavori: Giorgio leone e dora catalano Segretariato Generale della Presidenza massimo Sbardella collaboratori: alessandra montedoro della repubblica e maurizio occhetti Foto: G. -

PRINCE GIOVANNI BATTISTA PAMPHILJ (1648–1709) and the DISPLAY of ART in the PALAZZO AL COLLEGIO ROMANO, ROME Stephanie C. Leon

PRINCE GIOVANNI BATTISTA PAMPHILJ (1648–1709) AND THE DISPLAY OF ART IN THE PALAZZO AL COLLEGIO ROMANO, ROME Stephanie C. Leone, Boston College pon the death of his father Camillo in July 1666, Giovanni Battista Pamphilj’s legal status Uchanged dramatically: the eighteen-year-old prince became the primogenito of his wealthy and powerful family. With his inheritance came responsibilities, including the oversight of his father’s unfinished artistic projects at Sant’Agnese in Agone, Sant’Agostino, Sant’Andrea al Quirinale, the Collegio Innocenziano, and the Palazzo al Collegio Romano. The latter was the new wing, begun in 1659, which had been added to the Palazzo Aldobrandini al Corso (fig. 1), owned by his mother, Princess Olimpia Aldobrandini (1622–1681). After Olimpia, the sole heir to the great Aldrobrandini fortune, married Camillo Pamphilj in 1647, the couple moved into her palace rather than his, the Palazzo Pamphilj in Piazza Navona. The architect Antonio Del Grande designed Camillo’s new wing as a trapezoidal block to the northwest of the Aldobrandini property, between the Piazza al Col- legio Romano and the large courtyard (figs. 2, 3). Today, this unified palace is known as the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj al Corso. Under Camillo, construction was completed and the interior decoration was begun, but the task of outfitting the new rooms fell to Giovanni Battista.1 In this article—drawing on the information provided by two inventories of the palace’s con- tents, dating from ca. 1680 and 1709, respectively—I shall analyze and attempt to reconstruct the furnishings in Prince Pamphilj’s noble, winter, and mezzanine apartments.