The Importance of the New Start Treaty Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Strong Case for a New START a National Security Briefing Memo

A Strong Case for a New START A National Security Briefing Memo Max Bergmann and Samuel Charap April 6, 2010 What is New START and why do we need it? New START, the agreement between the United States and Russia on a successor to the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, is a historic achievement that will increase the United States’ safety and security. It will help us move beyond the outdated strategic approaches of the Cold War and reduce the threat of nuclear war, and marks a significant step in advancing President Barack Obama’s vision of a world without nuclear weapons. It also shows that his policy of constructive engagement with Russia is working. New START strengthens and modernizes the original START Treaty that President Ronald Reagan initiated in 1982 and George H.W. Bush signed in 1991. That agreement significantly reduced the number of nuclear weapons and launchers, but it also embodied Reagan’s favorite Russian proverb “trust but verify” by establishing an extensive verifica- tion and monitoring system to ensure compliance. This system helped build trust and mutual confidence that decreased the unimaginable consequences of а conflict between the world’s only nuclear superpowers. Yet President George W. Bush’s reckless policies left this cornerstone of nuclear stability’s fate in doubt. Bush effectively cut off relations between the United States and Russia on nuclear issues by unilaterally pulling out of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and refusing to engage in negotiations on a successor to START even though it was set to expire less than a year after he left office. -

Abigail Spanberger Has Been Endorsed by More Than 20 Liberal

Abigail Spanberger has been endorsed by more than 20 liberal groups—including NARAL and End Citizens United—and by more than 30 individuals, including Barack Obama, Joe Biden, and Justin Fairfax: • Spanberger was endorsed by more than 20 liberal groups, including End Citizens United, the New Dems, Moms Demand Action, and NARAL. Organizational Endorsements 1Planet AAPI Victory Fund (Asian American Pacific Islanders) Blue Wave Crowdsource Coalition to Stop Gun Violence EMILY’s List End Citizens United Foreign Policy for America (Foreign Policy Action Network) Human Rights Campaign J Street League of Conservation Voters Moms Demand Action MoveOn.org NARAL Pro-Choice America National Committee for an Effective Congress National Council to Preserve Social Security and Medicare National Women’s Political Caucus New Dem PAC Off the Sidelines Planned Parenthood Action Fund Population Connection Action Fund Serve America Virginia AFL-CIO Virginia Education Association Virginia PBA (Virginia Police Benevolent Association) Women Under Forty Political Action Committee • Spanberger was endorsed by more than 30 individuals, including President Barack Obama, Vice President Joe Biden, Senators Tim Kaine and Mark Warner, and Virginia Lt. Governor Justin Fairfax. Individual Endorsements Honorable Dawn Adams–House of Delegates, District 68 Honorable Lamont Bagby–House of Delegates, District 74 Larry Barnett–2017 Candidate for the 27th District of the Virginia House of Delegates Eileen Bedell–2016 and 2018 Democratic Candidate for Virginia’s 7th Congressional District Joe Biden–47th Vice President of the United States Tony Burgess–7th District Democratic Committee and Nottway County Democratic Committee Co-Chair Sheila Bynum-Coleman–2017 Democratic Candidate for the 62nd District of the Virginia House of Delegates James Corden Harold “Bud” Cothern, EdD.–Former Superintendent of Goochland County Public Schools Melissa Dart–2017 Democratic Candidate for the 56th District of the Virginia House of Delegates Clarence M. -

US Claims of Illegal Russian Nuclear Testing

Policy White Paper Analysis of Weapons-Related Security Threats and Effective Policy Responses U.S. Claims of Illegal Russian Nuclear Testing: Myths, Realities, and Next Steps By Daryl G. Kimball August 16, 2019 Executive Director, Arms Control Association n prepared remarks delivered at the Hudson Institute May 29, the Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), Lt. Gen. Robert Ashley, Jr., charged that “Russia probably is not adhering to its nuclear testing Imoratorium in a manner consistent with the ‘zero-yield’ standard outlined in the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT).” Russia has vigorously denied the allegation. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov called the accusation “a crude provocation” and pointed to the United States’ failure to ratify the CTBT. On June 12, Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said, “we are acting in full and absolute accordance with the treaty ratified by Moscow and in full accordance with our unilateral moratorium on nuclear tests.” The DIA director’s remarks, and a subsequent June 13 statement on the subject, are quite clearly part of an effort by Trump administration hardliners to suggest that Russia is conducting nuclear tests to improve its arsenal, and that the United States must be free of any constraints on its own nuclear weapons development effort, and, indirectly, to try to undermine the CTBT itself—a treaty the Trump administration has already said it will not ratify. The challenges posed by the new U.S. allegations are significant and they demand a proactive plan of action by “friends of the CTBT” governments for a number of reasons. HIGHLIGHTS • Any violation of the CTBT by Russia, which has signed • The Treaty’s Article I prohibition on “any nuclear weapons and ratified the agreement, or any other signatory, would test explosion, or any other nuclear explosion” bans all be a serious matter. -

Ibew Local Union 26 2020 Election Endorsements

IBEW LOCAL UNION 26 2020 ELECTION ENDORSEMENTS The Local 26 staff and the many activist members of our Union have met, interviewed, and questioned nu- merous candidates on both sides of the ballot. We have offered an olive branch to all candidates, in all parties. In some election races, neither candidate received our support. Our endorsements went only to those candidates who best served the members of Local 26, our families, and our future. Please use this endorsement list as a guide when casting your ballot. If you have any questions about registering, voting, ballot initiatives, or candi- dates please contact Tom Clark at 301-459-2900 Ext. 8804 or [email protected] US President/Vice President Joe Biden and Kamala Harris Maryland US House District 2: Dutch Ruppersberger US House District 3: John Sarbanes US House District 4: Anthony Brown US House District 5: Steny Hoyer US House District 6: David Trone US House District 7: Kweisi Mfume US House District 8: Jamie Raskin Question 1: YES Montgomery County Question A: For Question B: Against District of Columbia US House: Eleanor Holmes Norton DC Council at-large: Ed Lazere DC Council at-large: Robert White DC Council Ward 2: Brooke Pinto DC Council Ward 4: Janeese Lewis George DC Council Ward 7: Vincent Gray DC Council Ward 8: Trayon “Ward Eight” White Virginia US House District 1: Qasim Rashid US House District 2: Elaine Luria US House District 3: Bobby Scott US House District 4: Donald McEachin US House District 5: Dr. Cameron Webb US House District 7: Abigail Spanberger US House District 8: Don Beyer US House District 10: Jennifer Wexton US House District 11: Gerald Connolly Arlington Co Board Supervisors: Libby Garvey House of Delegates District 29: Irina Khanin Frederick County Board of Supervisors, Shawnee District: Richard Kennedy Luray Town Council: Leah Pence. -

Images and Dilemmas in International Relations

Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Images and Dilemmas in International Relations Dustin Tingley [email protected] Department of Government, Harvard University Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Introduction Three images of IR I Man I State I System Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Man Man Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Man Man I Motivations, dispositions, pathologies of individuals explains international affairs I \Human nature" matters I Quests for power/status essential because that is what individuals care about Associated with scholars like Hobbes, Morgenthau (at times), Rosen, and Tingley Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Man Man I Motivations, dispositions, pathologies of individuals explains international affairs I \Human nature" matters I Quests for power/status essential because that is what individuals care about Associated with scholars like Hobbes, Morgenthau (at times), Rosen, and Tingley Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Man Man I Motivations, dispositions, pathologies of individuals explains international affairs I \Human nature" matters I Quests for power/status essential because that is what individuals care about Associated with scholars like Hobbes, Morgenthau (at times), Rosen, and Tingley Introduction Man State System Security Dilemma Conclusion Man Man I Motivations, dispositions, pathologies of individuals explains international affairs I \Human nature" matters I Quests -

REPORT 2D Session HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES 104–582 "!

104TH CONGRESS REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 104±582 "! PROVIDING FOR THE CONSIDERATION OF H.R. 3144, THE DEFEND AMERICA ACT OF 1996 MAY 16, 1996.ÐReferred to the House Calendar and ordered to be printed Mr. DIAZ-BALART, from the Committee on Rules, submitted the following REPORT [To accompany H. Res. 438] The Committee on Rules, having had under consideration House Resolution 438, by a nonrecord vote, report the same to the House with the recommendation that the resolution be adopted. BRIEF SUMMARY OF PROVISIONS OF RESOLUTION The rule provides for consideration in the House with two hours of debate divided equally between the chairman and ranking mi- nority member of the Committee on National Security. The rule waives all points or order against the bill and against its consider- ation. The rule also makes in order without intervention of any point of order one minority amendment in the nature of a substitute to be offered by Mr. Spratt or his designee and which is printed in this report. The rule provides that the substitute shall be debatable separately for one hour divided equally between the proponent and an opponent. Finally, the rule provides for one motion to recommit with or without instructions. THE AMENDMENT TO BE OFFERED BY REPRESENTATIVE SPRATT OF SOUTH CAROLINA, OR A DESIGNEE, DEBATABLE FOR 1 HOUR Strike all after the enacting clause and insert the following: SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. This Act may be cited as the ``Ballistic Missile Defense Act of 1996''. SEC. 2. FINDINGS. Congress makes the following findings: 29±008 2 (1) Short-range theater ballistic missiles threaten United States Armed Forces wherever engaged abroad. -

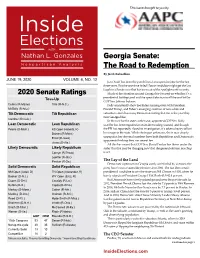

June 19, 2020 Volume 4, No

This issue brought to you by Georgia Senate: The Road to Redemption By Jacob Rubashkin JUNE 19, 2020 VOLUME 4, NO. 12 Jon Ossoff has been the punchline of an expensive joke for the last three years. But the one-time failed House candidate might get the last laugh in a Senate race that has been out of the spotlight until recently. 2020 Senate Ratings Much of the attention around Georgia has focused on whether it’s a Toss-Up presidential battleground and the special election to fill the seat left by GOP Sen. Johnny Isakson. Collins (R-Maine) Tillis (R-N.C.) Polls consistently show Joe Biden running even with President McSally (R-Ariz.) Donald Trump, and Biden’s emerging coalition of non-white and Tilt Democratic Tilt Republican suburban voters has many Democrats feeling that this is the year they turn Georgia blue. Gardner (R-Colo.) In the race for the state’s other seat, appointed-GOP Sen. Kelly Lean Democratic Lean Republican Loeffler has been engulfed in an insider trading scandal, and though Peters (D-Mich.) KS Open (Roberts, R) the FBI has reportedly closed its investigation, it’s taken a heavy toll on Daines (R-Mont.) her image in the state. While she began unknown, she is now deeply Ernst (R-Iowa) unpopular; her abysmal numbers have both Republican and Democratic opponents thinking they can unseat her. Jones (D-Ala.) All this has meant that GOP Sen. David Perdue has flown under the Likely Democratic Likely Republican radar. But that may be changing now that the general election matchup Cornyn (R-Texas) is set. -

Kazakhstan Missile Chronology

Kazakhstan Missile Chronology Last update: May 2010 As of May 2010, this chronology is no longer being updated. For current developments, please see the Kazakhstan Missile Overview. This annotated chronology is based on the data sources that follow each entry. Public sources often provide conflicting information on classified military programs. In some cases we are unable to resolve these discrepancies, in others we have deliberately refrained from doing so to highlight the potential influence of false or misleading information as it appeared over time. In many cases, we are unable to independently verify claims. Hence in reviewing this chronology, readers should take into account the credibility of the sources employed here. Inclusion in this chronology does not necessarily indicate that a particular development is of direct or indirect proliferation significance. Some entries provide international or domestic context for technological development and national policymaking. Moreover, some entries may refer to developments with positive consequences for nonproliferation. 2009-1947 March 2009 On 4 March 2009, Kazakhstan signed a contract to purchase S-300 air defense missile systems from Russia. According to Ministry of Defense officials, Kazakhstan plans to purchase 10 batteries of S-300PS by 2011. Kazakhstan's Air Defense Commander Aleksandr Sorokin mentioned, however, that the 10 batteries would still not be enough to shield all the most vital" facilities designated earlier by a presidential decree. The export version of S- 300PS (NATO designation SA-10C Grumble) has a maximum range of 75 km and can hit targets moving at up to 1200 m/s at a minimum altitude of 25 meters. -

Good Stuff Below. Thanks Again for Helping with the Meeting This Morning

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05794102 Date: 12/31/2015 RELEASE IN PART B6 From: Mills, Cheryl D <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, September 10, 2012 6:17 PM To: Subject: FW: President Obama Announces More Key Administration Posts FYI From: Brett McGurk Sent: Monday, September 10, 2012 5:48 PM To: Mills, Cheryl D Subject: FW: President Obama Announces More Key Administration Posts Good stuff below. Thanks again for helping with the meeting this morning. Bill followed up with me and we had a good talk. Brett ■ THE WHITE HOUSE Office of the Press Secretary FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 10, 2012 President Obama Announces More Key Administration Posts WASHINGTON, DC - Today, President Barack Obama announced his intent to nominate the following individuals to key Administration posts: • Robert Stephen Beecroft - Ambassador to the Republic of Iraq, Department of State • T. Charles Cooper - Assistant Administrator for Legislative and Public Affairs, United States Agency for International Development • Rose Gottemoeller - Under Secretary for Arms Control and International Security, Department of State President Obama said, "I am proud to nominate such impressive individuals to these important roles, and I am grateful they have agreed to lend their considerable talents to this Administration. I look forward to working with them in the months and years ahead." UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05794102 Date: 12/31/2015 UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05794102 Date: 12/31/2015 President ObaMa announced his intent to nominate the following individuals to key Administration posts: Ambassador Robert Stephen Beecroft, Nominee for Ambassador to the Republic of Iraq, Department of State Ambassador Robert Stephen Beecroft, a career member of the Senior Foreign Service, Class of Minister-Counselor, has served at the United States Embassy in Baghdad, Iraq as Deputy Chief of Mission since July 2011 and as Chargé d'Affaires since June 2012. -

Joe Rosochacki - Poems

Poetry Series Joe Rosochacki - poems - Publication Date: 2015 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Joe Rosochacki(April 8,1954) Although I am a musician, (BM in guitar performance & MA in Music Theory- literature, Eastern Michigan University) guitarist-composer- teacher, I often dabbled with lyrics and continued with my observations that I had written before in the mid-eighties My Observations are mostly prose with poetic lilt. Observations include historical facts, conjecture, objective and subjective views and things that perplex me in life. The Observations that I write are more or less Op. Ed. in format. Although I grew up in Hamtramck, Michigan in the US my current residence is now in Cumby, Texas and I am happily married to my wife, Judy. I invite to listen to my guitar works www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 A Dead Hand You got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, Know when to walk away and know when to run. You never count your money when you're sittin at the table. There'll be time enough for countin' when the dealins' done. David Reese too young to fold, David Reese a popular jack of all trades when it came to poker, The bluffing, the betting, the skill that he played poker, - was his ace of his sleeve. He played poker without deuces wild, not needing Jokers. To bad his lungs were not flushed out for him to breathe, Was is the casino smoke? Or was it his lifestyle in general? But whatever the circumstance was, he cashed out to soon, he had gone to see his maker, He was relatively young far from being too old. -

The Agenda for Arms Control Negotiations After the Moscow Treaty

The Agenda for Arms Control Negotiations After the Moscow Treaty PONARS Policy Memo 278 Nikolai Sokov Monterey Institute of International Studies October 2002 Ratification of the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT, or the Moscow Treaty), signed by Vladimir Putin and George W. Bush on May 24, 2002, is all but certain. Critics in both capitals have apparently been proven wrong—it turned out to be possible to break with three decades of arms control experience and traditions and to sign a treaty that almost completely lacks substantive provisions; even those that are included into the treaty cannot be efficiently verified. In contrast, this treaty exemplifies the Bush administration’s assertion that the United States and Russia no longer need complicated treaties that impose many restrictions on the maintenance, operation, and modernization of the two countries’ nuclear arsenals. Optimism about near unlimited flexibility, which the new treaty grants both sides, seems misguided, however. Although traditional concerns about a “bolt out of the blue” first strike have no place in the existing environment, both sides still need the reassurance and mutual trust that only a robust transparency regime could provide. Both sides have already proclaimed their intention to pursue further negotiations: the United States appears to favor the exchange of data whereas Russia seems more interested in measures that would limit the uploading capability of the United States. Either way, at issue is the predictability of the U.S.-Russia strategic relationship. The stable cooperative relations between the United States and Russia offer an opportunity that should not be missed. The two sides feel reasonably safe vis-à-vis one another and can afford approaching transparency negotiations without undue haste. -

The Breach: Ukraine's Territorial Integrity and the Budapest Memorandum

Issue Brief #3 Nuclear Proliferation International History Project The Breach: Ukraine’s Territorial Integrity and the Budapest Memorandum Mariana Budjeryn Russia’s annexation of Crimea and covert invasion of eastern Ukraine places an uncomfortable focus on the worth of the security assurances pledged to Ukraine by the nuclear powers in exchange for its denuclearization. In 1994, the three depository states of the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT)—Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom—extended positive and negative security assurances to Ukraine. The depository states underlined their commitment to Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity by signing the so-called “Budapest Memorandum.”1 Using new archival records, this examination of Ukraine’s search for security guarantees in the early 1990s reveals that, ironically, the threat of border revisionism by Russia was the single gravest concern of Ukraine’s leadership when surrendering the nuclear arsenal. The failure of the Budapest Memorandum to deter one of Ukraine’s security guarantors from military aggression has important implications both for Ukraine’s long-term security and for the value of security assurances for future international nonproliferation and disarmament efforts. Russia’s breach of the Memorandum invites strong scrutiny of other security commitments and opens an enormous rhetorical opportunity for proliferators to lobby for a nuclear deterrent. UKRAINE’S NUCLEAR PREDICAMENT In 1991, Ukraine inherited the world’s third largest more cautious approach to its nuclear inheritance, nuclear arsenal as a result of the collapse of the concerned that Russia’s monopoly on nuclear arms Soviet Union.2 By mid-1996, all nuclear munitions in the post-Soviet space would be conducive to its had been transferred from Ukraine to Russia resurgence as a dominating force in the region.