HIST 690 Forensic Illusions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legal Collections Catalogue

Legal Collections Catalogue ©National Justice Museum 1 Introduction The catalogue is in entry number order and lists most collections at individual item level. The catalogue lists each collections entry number, description, date range, and accession numbers. There are two indexes for this catalogue: a subject index and a name index, both of which are arranged in alphabetical order. Enquirers can only request five items at any one time to view. When requesting items for viewing please note down the entry or loan number, and accession number, as this will assist retrieval from the storage areas. ©National Justice Museum 2 E1 Framed facsimile of the original warrant for the beheading of 1648 1995.1 Charles I E6 Collection of legal costume and documents related to Charles 1891-1966 1995.9 Rothera, Coroner of Nottingham E6 Coroner’s robe by Ede & Son belonging to Charles Rothera, 1891-1934 1995.9.1 Coroner of Nottingham E6 Coroner’s wig made by Ravenscroft Star Lincoln’s Inn Fields 1891-1934 1995.9.2 belonging to Charles Rothera E6 Wig box by Ravenscroft Law Wig & Robe Maker belonging to 1891-1934 1995.9.3 Charles Rothera E6 Pair of white cotton gloves belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.4 E6 Pair of white cotton gloves, elasticated wrist belonging to Charles 1891-1934 1995.9.5 Rothera E6 Collar (wing) belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.6 E6 Collar belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.7 E6 Tab wallet by Ede & Ravenscroft belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.8 E6 Tab, button & elastic fastening belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.9 E6 Tab, metal ring & hook and eye fastening belonging to Charles 1891-1934 1995.9.10 Rothera E6 Tab tape tie fastening belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.11 E6 Tab tape tie fastening belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.12 E6 Letter to C. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1963-06-15

1'1 First 'La'dy Cosmonaut May Be Launched ,dall MOSCOW (AP) - The SO- I nau~ in ~ p~ralJel orbit sometime craft was not given. Previous So· The Bykovsky flight puts the Popovich aloft at the same time An excbange ol radJatelepbooe you In our homelaDd," he said. pose II to contlDue sl1IdiN 01 the rea· viet Union's fifth cosmonaut during hi S fligh t. viet space ships have weighed five Soviet Union one-up on the United as "The Heavenly Twins" in mid· messag between KbnIsbchev and Bykovsky said he w protouodly tnfIUl'IJ(!e of varioul fllC1Ol'l III . PREMIER KHRUSHCHEV also tons. States in manned orbital missions August 1962, Wilson asked how the cosmonaut was publicized by moved. He thanked the premier space nJgblln the bUDIIII bod)' IIId 'ne: circled the earth FrIday mght hinted at an extended flight in an· There was no official confirma. and prospects are that there will many were up this time. Tass. "!rom the bottom of my heart for to study eooditiona of a kloi fliIht. and \lnofficinl Com m u n i s t nouncing that Bykovsky was in or· tion that a woman was ready to be no further challenge from "Only one so far," Khrushchev Bykovsky reported to the Com· your fatherly .... "_, ..... _... This iDd~ted ~t Bykovaty may 0[[ sources S81'd a woman WOll Id bitA' M t I . ... take but the reports said Mos· across the Atlantic for more than said. munist party, the Government aDd .,v"""..... be up quite while. F we . -

An Affair of State: the Profumo Case And

Also by Phillip Knightley THE SECOND OLDEST PROFESSION AN AFFAIR The Spy as Bureaucrat, Patriot, Fantasist and Whore THE FIRST CASUALTY From the Crimea to Vietnam, OF STATE the War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist and Myth-maker THE PROFUMO CASE THE VESTEY AFFAIR AND THE THE DEATH OF VENICE FRAMING- OF STEPHEN WARD (co-author) SUFFER THE CHILDREN The Story of Thalidomide (co-author) Phillip Knightley THE SECRET LIVES OF LAWRENCE OF ARABIA and (co-author) Caroline Kennedy PHILBY THE SPY WHO BETRAYED A GENERATION (co-author) JONATHAN CAPE THIRTY-TWO BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON CONTENTS For Elisar, Mayumi, Jasmine, Aliya, Marisa and Kim - Introduction and for Stephen Ward Acknowledgments Scandal in High Places 2 The Crusading Osteopath 3 Ward Cracks the Social Scene 4 A Magnet for Girls 5 A Rising Star in the Tory Party 33 6 The Waif and the Crooked Businessman 37 7 Delightful Days at Cliveden 46 8 The Promiscuous Showgirl 53 9 Living Together 58 to The Artist and the Royals 61 I Enter Ivanov, Soviet Spy 67 12 Mandy and Christine Run Riot 78 13 Astor's Summer Swimming Party 84 14 Playing International Politics 90 15 Wigg Seeks Revenge 93 16 The FBI and the London Call Girl 97 First published 1987 17 The New York Caper Too Copyright © 1987 by Phillip Knightley and Caroline Kennedy 18 Cooling the Cuban Missile Crisis 1os Jonathan Cape Ltd, 32 Bedford Square, London acts JEL 19 Problems with Profumo 113 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data 20 A Knife Fight in Soho 117 21 A Shooting in Marylebone 121 Knightley, Phillip An affair of state: the Profumo case and zz Ward Stops the Presses 129 the framing of Stephen Ward 23 The Police Show Interest 138 1. -

Bruised Witness: Bernard Spilsbury and the Performance of Early Twentieth-Century English Forensic Pathology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central Medical History, 2011, 55: 41–60 Bruised Witness: Bernard Spilsbury and the Performance of Early Twentieth-Century English Forensic Pathology IAN BURNEY and NEIL PEMBERTON* Abstract: This article explores the status, apparatus and character of forensic pathology in the inter-war period, with a special emphasis on the ‘people’s pathologist’, Bernard Spilsbury. The broad expert and pub- lic profile of forensic pathology, of which Spilsbury was the most promi- nent contemporary representative, will be outlined and discussed. In so doing, close attention will be paid to the courtroom strategies by which he and other experts translated their isolated post-mortem encounters with the dead body into effective testimony. Pathologists built a high-profile practice that transfixed the popular, legal and scientific imagination, and this article also explores, through the celebrated 1925 murder trial of Norman Thorne, how Spilsbury’s courtroom performance focused critical attention on the practices of pathology itself, which threatened to destabilise the status of forensic pathology. In particular, the Thorne case raised questions about the inter- relation between bruising and putrefaction as sources of interpretative anxiety. Here, the question of practice is vital, especially in understand- ing how Spilsbury’s findings clashed with those of rival pathologists whose autopsies centred on a corpse that had undergone further putrefac- tive changes and that had thereby mutated as an evidentiary object. Examining how pathologists dealt with interpretative problems raised by the instability of their core investigative object enables an analysis of the ways in which pathological investigation of homicide was inflected with a series of conceptual, professional and cultural difficul- ties stemming in significant ways from the materiality of the corpse itself. -

Anoufae62.261� LARGEST CIRCULATION of ANY PAPER .IN11 AMERICA J PAGE 6) to *,Nvestigatoris 12-Year Probe Reveals

TiONAL 30' May 4, 1976 ANOUfAE62.261 LARGEST CIRCULATION OF ANY PAPER .IN11 AMERICA j PAGE 6) To *,nvestigatoris 12-Year Probe Reveals. sSossin Was Trained as .0.001d .Double • , . , Michael . Eddesies;'-eneted I ilsh. Invesil--7 T "-..` 1 '.. • ' t --- gotPre writer, won wide wreaks,' In Europe %lop nvestgator s 12-Year Probe Reveals . .---"-- by proving thot,Timothy Evans, an English- Man' who Wei mistakenly hanged - ler the. - . murder of‘,his baby daughter, was Innocent - of the crime. Evans was given sr posthumous F ' Was• Killed, „._,. ... by, a Russ;, . end pardon offer Eddowes proved beyond a doubt ., that the reel killee W(.12 mail murderer John _. Reginald Holliday Christie. In his new beak, "November • 22 — How They killed Kennedy," Eddowes presents shocking new evidence that a Russian KGB agent, posing as Lee Harvey Orweldi assassinated President Keene,* A spokesman for Sen. Richard Schweiker IR.-Pe.), who heeds a Senate suheomnsittee investigating the JFK assassination. told The ENQUIR- ER: "fletaose of Mr..Eddowel' previous record in the Timothy Evens case, the panel is taking a very careful 'and serious look at the information he has supplied an Lee Herter COtir4TY MroiCikt: EXAMINER Oswald and the isssasilnation 'of President Kennedy." ...••., - • . ... • • ' • ••• ,. • By WILLIAM DICK and ART DWORKEN . -, ' , . – •. .,. 1111. !..1, r President John F. {Kennedy was slain :by a Russian KGB, agent posing as Lee HarVey Oswald, says British author Michael Eddowes )4,t.., /,,,7 .n.v.t*ri . if4.3...)56 after a 12-year investigation of the crime of the century. • , rit,-;11 (KINLIA, Lee HoTroT ranal Vlitn Cris, lid* Eddowes, 72, one of England's foremost investigative writers, has 1, published a new book unraveling what he describes' as a devious Soviet i,k-1.001 &Itelt 11-24-63, a/45 r..K. -

St Catharine's Thespians Have Been in the News Name for a Professor of Economic History

St Catharine’s 2014 St Catharine’s Magazine !"#$ Printed in England by Langham Press Ltd (www.langhampress.co.uk) on Picture credits: Cover: Tim Harvey-Samuel; pp5, elemental-chlorine-free paper from 27 (both): Alexander Dodd; pp6, 17, 19, 21, 23 sustainable forests. (thumbnail): Julian Johnson (JJPortraits.co.uk); p9: Jean Thomas; pp18, 20: Tim Rawle; p29: Ella Jackson, p82 Designed and typeset in Linotype Syntax by (left): Andy Rapkins; pp107, 108: Cambridge Collection. Hamish Symington (www.hamishsymington.com). Table of contents Editorial ............................................................4 Society Report Society Committee 2013–14 ...........................56 College Report The Society President ......................................56 Master’s Report ................................................6 Ancient and Modern – Nine Decades ..............57 The Fellowship ................................................11 Report of 86th AGM ......................................57 New Fellows ...................................................14 Accounts for the year to 30 June 2014 ...........61 Retirements and Farewells ..............................15 Society Awards ...............................................62 Professor Sir Peter Hall (1932–2014) ..............16 Society Presidents’ Dinner ...............................62 Senior Tutors’ Reports .....................................17 The Acheson Gray Sports Day 2014 ...............63 Notes from the Admissions Tutor ....................19 Branch News ..................................................64 -

Stephen Ward

How The English Establishment Framed STEPHEN WARD Caroline Kennedy & Phillip Knightley with additional material by Caroline Kennedy Copyright Phillip Knightley & Caroline Kennedy 2013 All rights reserved. ISBN: XXXXXX ISBN 13: XXXXX Library of Congress Control Number: XXXXX (If applicable) LCCN Imprint Name: City and State (If applicable) INTRODUCTION It was in the attic of an old English farmhouse, on a lovely autumn evening in September 1984, that this book had its beginnings. Two years earlier Caroline Kennedy, doing some research for a television film, had arrived at this same house to interview the owner, Pelham Pound. As they talked she found out he was an old friend of her late brother-in-law, Dominick Elwes. Later in the day the discussion turned to Elwes's friendship with Dr Stephen Ward, the society osteopath, who had committed suicide at the height of the Profumo scandal in 1963. Elwes, her host said, had stood bail for Stephen Ward, had worked with him on a proposed television programme about his life and had produced a film entitled, The Christine Keeler Story. In a trunk in his attic, Pound explained, he had tape recordings and scripts that Elwes had given him years ago. Would she be interested in taking a look some time? Caroline Kennedy was intrigued. Like nearly everyone else she remembered the Profumo scandal but only faintly remembered Ward. So, on her return visit that autumn evening, after riffling through the contents of the trunk, she returned home with a box full of old letters, voluminous pages of handwritten and typed filmscript and reels of tape. -

The Abolition of the Death Penalty in the United Kingdom

The Abolition of the Death Penalty in the United Kingdom How it Happened and Why it Still Matters Julian B. Knowles QC Acknowledgements This monograph was made possible by grants awarded to The Death Penalty Project from the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, the United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the Sigrid Rausing Trust, the Oak Foundation, the Open Society Foundation, Simons Muirhead & Burton and the United Nations Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture. Dedication The author would like to dedicate this monograph to Scott W. Braden, in respectful recognition of his life’s work on behalf of the condemned in the United States. © 2015 Julian B. Knowles QC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Copies of this monograph may be obtained from: The Death Penalty Project 8/9 Frith Street Soho London W1D 3JB or via our website: www.deathpenaltyproject.org ISBN: 978-0-9576785-6-9 Cover image: Anti-death penalty demonstrators in the UK in 1959. MARY EVANS PICTURE LIBRARY 2 Contents Foreword .....................................................................................................................................................4 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................5 A brief -

Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE

Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE Steven B. Karch, MD, SERIES EDITOR CRIMINAL POISONING: INVESTIGATIONAL GUIDE FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT, TOXICOLOGISTS, FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, AND ATTORNEYS, SECOND EDITION, by John H. Trestrail, III, 2007 MARIJUANA AND THE CANNABINOIDS, edited by Mahmoud A. ElSohly, 2007 FORENSIC PATHOLOGY OF TRAUMA: COMMON PROBLEMS FOR THE PATHOLOGIST, edited by Michael J. Shkrum and David A. Ramsay, 2007 THE FORENSIC LABORATORY HANDBOOK: PROCEDURES AND PRACTICE, edited by Ashraf Mozayani and Carla Noziglia, 2006 SUDDEN DEATHS IN CUSTODY, edited by Darrell L. Ross and Ted Chan, 2006 DRUGS OF ABUSE: BODY FLUID TESTING, edited by Raphael C. Wong and Harley Y. Tse, 2005 A PHYSICIAN’S GUIDE TO CLINICAL FORENSIC MEDICINE: SECOND EDITION, edited by Margaret M. Stark, 2005 FORENSIC MEDICINE OF THE LOWER EXTREMITY: HUMAN IDENTIFICATION AND TRAUMA ANALYSIS OF THE THIGH, LEG, AND FOOT, by Jeremy Rich, Dorothy E. Dean, and Robert H. Powers, 2005 FORENSIC AND CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF SOLID PHASE EXTRACTION, by Michael J. Telepchak, Thomas F. August, and Glynn Chaney, 2004 HANDBOOK OF DRUG INTERACTIONS: A CLINICAL AND FORENSIC GUIDE, edited by Ashraf Mozayani and Lionel P. Raymon, 2004 DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS: TOXICOLOGY AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, edited by Melanie Johns Cupp and Timothy S. Tracy, 2003 BUPRENOPHINE THERAPY OF OPIATE ADDICTION, edited by Pascal Kintz and Pierre Marquet, 2002 BENZODIAZEPINES AND GHB: DETECTION AND PHARMACOLOGY, edited by Salvatore J. Salamone, 2002 ON-SITE DRUG TESTING, edited by Amanda J. Jenkins and Bruce A. Goldberger, 2001 BRAIN IMAGING IN SUBSTANCE ABUSE: RESEARCH, CLINICAL, AND FORENSIC APPLICATIONS, edited by Marc J. Kaufman, 2001 CRIMINAL POISONING INVESTIGATIONAL GUIDE FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT, TOXICOLOGISTS, FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, AND ATTORNEYS Second Edition John Harris Trestrail, III, RPh, FAACT, DABAT Center for the Study of Criminal Poisoning, Grand Rapids, MI © 2007 Humana Press Inc. -

Capital Domicide: Home and Murder in the Mid-Century Metropolis

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Capital Domicide: Home and Murder in the Mid-Century Metropolis Alexa Hannah Leah Neale Submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex November 2015 1 Contents Summary .......................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 3 List of figures ................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations .................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter one: sources.................................................................................................... -

Appendix: Some Common Homicidal Poisons

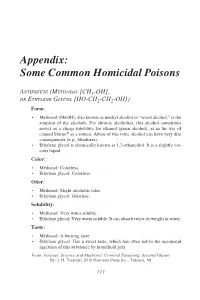

Appendix 111 Appendix: Some Common Homicidal Poisons ANTIFREEZE (METHANOL [CH3-OH], OR ETHYLENE GLYCOL [HO-CH2-CH2-OH]) Form: • Methanol (MeOH), also known as methyl alcohol or “wood alcohol,” is the simplest of the alcohols. For chronic alcoholics, this alcohol sometimes serves as a cheap substitute for ethanol (grain alcohol), as in the use of canned Sterno® as a source. Abuse of this toxic alcohol can have very dire consequences (e.g., blindness). • Ethylene glycol is chemically known as 1,2-ethanediol. It is a slightly vis- cous liquid. Color: • Methanol: Colorless. • Ethylene glycol: Colorless. Odor: • Methanol: Slight alcoholic odor. • Ethylene glycol: Odorless. Solubility: • Methanol: Very water soluble. • Ethylene glycol: Very water soluble. It can absorb twice its weight in water. Taste: • Methanol: A burning taste. • Ethylene glycol: Has a sweet taste, which has often led to the accidental ingestion of this substance by household pets. From: Forensic Science and Medicine: Criminal Poisoning, Second Edition By: J. H. Trestrail, III © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ 111 112 Common Homicidal Poisons Source: • Methanol: Is a common ingredient in windshield-washing solutions, dupli- cating fluids, and paint removers and is commonly found in gas-line anti- freeze, which may be 95% (v/v) methanol. • Ethylene glycol: Is commonly found in radiator antifreeze (in a concentration of ~95% [v/v]), and antifreeze products used in heating and cooling systems. Lethal Dose: • Methanol: The fatal dose is estimated to be 30–240 mL (20–150 g). • Ethylene glycol: The approximate fatal dose of 95% ethylene glycol is esti- mated to be 1.5 mL/kg. -

Sex & Crime Feature

SEX & CRIME IN HANDWRITING - BY BRIGITTE APPLEGARTH MDIP (BIG) Lecture given to The British Institutes of Graphologists (quarterly meeting) at the Soroptomist Club, London on 13 June 2015 I thought it might be fun to do a “look and learn” session with other graphologists - and what is more fun in graphology than Sex and Crime? One of the best things about our meetings is that we can hear other people’s views and experiences with practical analysis. It gives us the chance to reinforce and update our separate knowledge base with both students and experienced graphologists. Whilst giving this presentation to members of the Women’s Institutes and other interested parties, I found that almost everyone has had an experience with handwriting that caused them to analyse the authors psyche. It’s always rewarding to get an interaction with the audience and interesting points arise, even though they’re new to the concept and workings of graphology. I always include a quick analysis break. “I wish I had known about this years ago” and “Staggered” seem to be the most popular retorts, as they start to look over each other’s shoulders at their handwriting. I suppose in a few years’ time they will be saying “Amazing” and “Awesome” - if I’m still around by then! At first, opinions range from coincidence to scepticism to predictive quality. Although as soon as anyone likens it to a fortune telling tool, I feel compelled to interject, and put them right. Somehow that does not sit easily with me and comparing graphology to astrology only subtracts from its credence.