Some of the Most Difficult Cases Forensic Pathologists Usually

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legal Collections Catalogue

Legal Collections Catalogue ©National Justice Museum 1 Introduction The catalogue is in entry number order and lists most collections at individual item level. The catalogue lists each collections entry number, description, date range, and accession numbers. There are two indexes for this catalogue: a subject index and a name index, both of which are arranged in alphabetical order. Enquirers can only request five items at any one time to view. When requesting items for viewing please note down the entry or loan number, and accession number, as this will assist retrieval from the storage areas. ©National Justice Museum 2 E1 Framed facsimile of the original warrant for the beheading of 1648 1995.1 Charles I E6 Collection of legal costume and documents related to Charles 1891-1966 1995.9 Rothera, Coroner of Nottingham E6 Coroner’s robe by Ede & Son belonging to Charles Rothera, 1891-1934 1995.9.1 Coroner of Nottingham E6 Coroner’s wig made by Ravenscroft Star Lincoln’s Inn Fields 1891-1934 1995.9.2 belonging to Charles Rothera E6 Wig box by Ravenscroft Law Wig & Robe Maker belonging to 1891-1934 1995.9.3 Charles Rothera E6 Pair of white cotton gloves belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.4 E6 Pair of white cotton gloves, elasticated wrist belonging to Charles 1891-1934 1995.9.5 Rothera E6 Collar (wing) belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.6 E6 Collar belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.7 E6 Tab wallet by Ede & Ravenscroft belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.8 E6 Tab, button & elastic fastening belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.9 E6 Tab, metal ring & hook and eye fastening belonging to Charles 1891-1934 1995.9.10 Rothera E6 Tab tape tie fastening belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.11 E6 Tab tape tie fastening belonging to Charles Rothera 1891-1934 1995.9.12 E6 Letter to C. -

Bruised Witness: Bernard Spilsbury and the Performance of Early Twentieth-Century English Forensic Pathology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central Medical History, 2011, 55: 41–60 Bruised Witness: Bernard Spilsbury and the Performance of Early Twentieth-Century English Forensic Pathology IAN BURNEY and NEIL PEMBERTON* Abstract: This article explores the status, apparatus and character of forensic pathology in the inter-war period, with a special emphasis on the ‘people’s pathologist’, Bernard Spilsbury. The broad expert and pub- lic profile of forensic pathology, of which Spilsbury was the most promi- nent contemporary representative, will be outlined and discussed. In so doing, close attention will be paid to the courtroom strategies by which he and other experts translated their isolated post-mortem encounters with the dead body into effective testimony. Pathologists built a high-profile practice that transfixed the popular, legal and scientific imagination, and this article also explores, through the celebrated 1925 murder trial of Norman Thorne, how Spilsbury’s courtroom performance focused critical attention on the practices of pathology itself, which threatened to destabilise the status of forensic pathology. In particular, the Thorne case raised questions about the inter- relation between bruising and putrefaction as sources of interpretative anxiety. Here, the question of practice is vital, especially in understand- ing how Spilsbury’s findings clashed with those of rival pathologists whose autopsies centred on a corpse that had undergone further putrefac- tive changes and that had thereby mutated as an evidentiary object. Examining how pathologists dealt with interpretative problems raised by the instability of their core investigative object enables an analysis of the ways in which pathological investigation of homicide was inflected with a series of conceptual, professional and cultural difficul- ties stemming in significant ways from the materiality of the corpse itself. -

St Catharine's Thespians Have Been in the News Name for a Professor of Economic History

St Catharine’s 2014 St Catharine’s Magazine !"#$ Printed in England by Langham Press Ltd (www.langhampress.co.uk) on Picture credits: Cover: Tim Harvey-Samuel; pp5, elemental-chlorine-free paper from 27 (both): Alexander Dodd; pp6, 17, 19, 21, 23 sustainable forests. (thumbnail): Julian Johnson (JJPortraits.co.uk); p9: Jean Thomas; pp18, 20: Tim Rawle; p29: Ella Jackson, p82 Designed and typeset in Linotype Syntax by (left): Andy Rapkins; pp107, 108: Cambridge Collection. Hamish Symington (www.hamishsymington.com). Table of contents Editorial ............................................................4 Society Report Society Committee 2013–14 ...........................56 College Report The Society President ......................................56 Master’s Report ................................................6 Ancient and Modern – Nine Decades ..............57 The Fellowship ................................................11 Report of 86th AGM ......................................57 New Fellows ...................................................14 Accounts for the year to 30 June 2014 ...........61 Retirements and Farewells ..............................15 Society Awards ...............................................62 Professor Sir Peter Hall (1932–2014) ..............16 Society Presidents’ Dinner ...............................62 Senior Tutors’ Reports .....................................17 The Acheson Gray Sports Day 2014 ...............63 Notes from the Admissions Tutor ....................19 Branch News ..................................................64 -

Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE

Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE Steven B. Karch, MD, SERIES EDITOR CRIMINAL POISONING: INVESTIGATIONAL GUIDE FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT, TOXICOLOGISTS, FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, AND ATTORNEYS, SECOND EDITION, by John H. Trestrail, III, 2007 MARIJUANA AND THE CANNABINOIDS, edited by Mahmoud A. ElSohly, 2007 FORENSIC PATHOLOGY OF TRAUMA: COMMON PROBLEMS FOR THE PATHOLOGIST, edited by Michael J. Shkrum and David A. Ramsay, 2007 THE FORENSIC LABORATORY HANDBOOK: PROCEDURES AND PRACTICE, edited by Ashraf Mozayani and Carla Noziglia, 2006 SUDDEN DEATHS IN CUSTODY, edited by Darrell L. Ross and Ted Chan, 2006 DRUGS OF ABUSE: BODY FLUID TESTING, edited by Raphael C. Wong and Harley Y. Tse, 2005 A PHYSICIAN’S GUIDE TO CLINICAL FORENSIC MEDICINE: SECOND EDITION, edited by Margaret M. Stark, 2005 FORENSIC MEDICINE OF THE LOWER EXTREMITY: HUMAN IDENTIFICATION AND TRAUMA ANALYSIS OF THE THIGH, LEG, AND FOOT, by Jeremy Rich, Dorothy E. Dean, and Robert H. Powers, 2005 FORENSIC AND CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF SOLID PHASE EXTRACTION, by Michael J. Telepchak, Thomas F. August, and Glynn Chaney, 2004 HANDBOOK OF DRUG INTERACTIONS: A CLINICAL AND FORENSIC GUIDE, edited by Ashraf Mozayani and Lionel P. Raymon, 2004 DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS: TOXICOLOGY AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, edited by Melanie Johns Cupp and Timothy S. Tracy, 2003 BUPRENOPHINE THERAPY OF OPIATE ADDICTION, edited by Pascal Kintz and Pierre Marquet, 2002 BENZODIAZEPINES AND GHB: DETECTION AND PHARMACOLOGY, edited by Salvatore J. Salamone, 2002 ON-SITE DRUG TESTING, edited by Amanda J. Jenkins and Bruce A. Goldberger, 2001 BRAIN IMAGING IN SUBSTANCE ABUSE: RESEARCH, CLINICAL, AND FORENSIC APPLICATIONS, edited by Marc J. Kaufman, 2001 CRIMINAL POISONING INVESTIGATIONAL GUIDE FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT, TOXICOLOGISTS, FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, AND ATTORNEYS Second Edition John Harris Trestrail, III, RPh, FAACT, DABAT Center for the Study of Criminal Poisoning, Grand Rapids, MI © 2007 Humana Press Inc. -

Capital Domicide: Home and Murder in the Mid-Century Metropolis

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Capital Domicide: Home and Murder in the Mid-Century Metropolis Alexa Hannah Leah Neale Submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex November 2015 1 Contents Summary .......................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 3 List of figures ................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations .................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter one: sources.................................................................................................... -

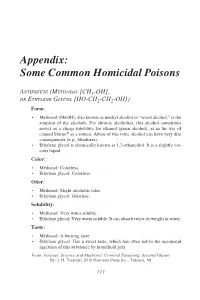

Appendix: Some Common Homicidal Poisons

Appendix 111 Appendix: Some Common Homicidal Poisons ANTIFREEZE (METHANOL [CH3-OH], OR ETHYLENE GLYCOL [HO-CH2-CH2-OH]) Form: • Methanol (MeOH), also known as methyl alcohol or “wood alcohol,” is the simplest of the alcohols. For chronic alcoholics, this alcohol sometimes serves as a cheap substitute for ethanol (grain alcohol), as in the use of canned Sterno® as a source. Abuse of this toxic alcohol can have very dire consequences (e.g., blindness). • Ethylene glycol is chemically known as 1,2-ethanediol. It is a slightly vis- cous liquid. Color: • Methanol: Colorless. • Ethylene glycol: Colorless. Odor: • Methanol: Slight alcoholic odor. • Ethylene glycol: Odorless. Solubility: • Methanol: Very water soluble. • Ethylene glycol: Very water soluble. It can absorb twice its weight in water. Taste: • Methanol: A burning taste. • Ethylene glycol: Has a sweet taste, which has often led to the accidental ingestion of this substance by household pets. From: Forensic Science and Medicine: Criminal Poisoning, Second Edition By: J. H. Trestrail, III © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ 111 112 Common Homicidal Poisons Source: • Methanol: Is a common ingredient in windshield-washing solutions, dupli- cating fluids, and paint removers and is commonly found in gas-line anti- freeze, which may be 95% (v/v) methanol. • Ethylene glycol: Is commonly found in radiator antifreeze (in a concentration of ~95% [v/v]), and antifreeze products used in heating and cooling systems. Lethal Dose: • Methanol: The fatal dose is estimated to be 30–240 mL (20–150 g). • Ethylene glycol: The approximate fatal dose of 95% ethylene glycol is esti- mated to be 1.5 mL/kg. -

Sex & Crime Feature

SEX & CRIME IN HANDWRITING - BY BRIGITTE APPLEGARTH MDIP (BIG) Lecture given to The British Institutes of Graphologists (quarterly meeting) at the Soroptomist Club, London on 13 June 2015 I thought it might be fun to do a “look and learn” session with other graphologists - and what is more fun in graphology than Sex and Crime? One of the best things about our meetings is that we can hear other people’s views and experiences with practical analysis. It gives us the chance to reinforce and update our separate knowledge base with both students and experienced graphologists. Whilst giving this presentation to members of the Women’s Institutes and other interested parties, I found that almost everyone has had an experience with handwriting that caused them to analyse the authors psyche. It’s always rewarding to get an interaction with the audience and interesting points arise, even though they’re new to the concept and workings of graphology. I always include a quick analysis break. “I wish I had known about this years ago” and “Staggered” seem to be the most popular retorts, as they start to look over each other’s shoulders at their handwriting. I suppose in a few years’ time they will be saying “Amazing” and “Awesome” - if I’m still around by then! At first, opinions range from coincidence to scepticism to predictive quality. Although as soon as anyone likens it to a fortune telling tool, I feel compelled to interject, and put them right. Somehow that does not sit easily with me and comparing graphology to astrology only subtracts from its credence. -

HIST 690 Forensic Illusions

1 HIST 690 Forensic illusions: Medico-legal representations, scandals and reform in mid-twentieth century Britain, Canada and New Zealand By Mei-Chien Huang Primary Supervisor: Heather Wolffram Secondary Supervisor: David Monger February 2020 This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History at the University of Canterbury. This thesis is the result of my own work. Material from the published or unpublished work of other historians used in the thesis is credited to the author in the footnote references. The thesis is approximately 47,600 words in length. 2 3 Abstract The media representations of charismatic medico-legists from the British Commonwealth and of the wondrous powers of forensic medicine greatly influenced the perception of the discipline’s reliability and accuracy during the twentieth century. However, as recent reports of crises in the forensic sciences show, the irrefutability of scientific evidence is illusionary. While some scholars have argued that reforms in the forensic sciences were triggered by scandals, this thesis shows that this was not the case during the mid-twentieth century. This work expands on the existing secondary sources on the history of forensic medicine and forensic science by comparing the British, Canadian and New Zealand traditions, and the way forensic pathologists portrayed themselves in the media and through their own writings. It focuses on three notable miscarriage of justice cases, that of Timothy Evans, Steven Truscott and Eric Mareo, to demonstrate how medico-legists successfully minimised the impact of potential scandals in forensic medicine by presenting a united front. -

Overseas 2018

overSEAS 2018 This thesis was submitted by its author to the School of English and American Studies, Eötvös Loránd University, in partial ful- filment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts. It was found to be among the best theses submitted in 2018, therefore it was decorated with the School’s Outstanding Thesis Award. As such it is published in the form it was submitted in overSEAS 2018 (http://seas3.elte.hu/overseas/2018.html) ALAPSZAKOS SZAKDOLGOZAT Józsika Nikolett Anglisztika alapszak Angol szakirány 2018 CERTIFICATE OF RESEARCH By my signature below, I certify that my ELTE B.A. thesis, entitled An Unlikely Public Idol: Bernard Spilsbury and the Derailment of Criminal Justice 1910-1947 is entirely the result of my own work, and that no degree has previously been conferred upon me for this work. In my thesis I have cited all the sources (printed, electronic or oral) I have used faithfully and have always indicated their origin. The electronic version of my thesis (in PDF format) is a true representation (identical copy) of this printed version. If this pledge is found to be false, I realize that I will be subject to penalties up to and including the forfeiture of the degree earned by my thesis. Date: 2018.04.09. Signed: ........................................................... EÖTVÖS LORÁND TUDOMÁNYEGYETEM Bölcsészettudomány Kar ALAPSZAKOS SZAKDOLGOZAT Valószerűtlen hős: Bernard Spilsbury és a brit igazságszolgáltatás kisiklatása 1910-1947 An Unlikely Public Idol: Bernard Spilsbury and the Derailment of Criminal Justice 1910-1947 Témavezető: Készítette: Dr. Lojkó Miklós Józsika Nikolett habilitált egyetemi docens anglisztika alapszak angol szakirány 2018 CONTENTS Abstract Introduction 1 Chapter 1. -

Appendix: COMMON HOMICIDAL POISONS

ApPENDIX: COMMON HOMICIDAL POISONS 105 APPENDIX 107 ARSENIC Form: Metallic arsenic (As) is a steel-gray, brittle metal. Arsenic trichlo ride (AsCI3) is an oily liquid. Arsenic trioxide (AS:203) is a crystalline solid. It can also exist as arsine gas (AsH3). Lewisite, a war gas, is a deriva tive of arsine. Color: Metal (steel-gray), salts (white powder). Odor: Odorless, but arsenic can produce a garlicky odor to the breath. Solubility: Arsenical salts are water-soluble. Taste: Almost tasteless. Source: Pesticides, rodent poison, ant poison, homeopathic medications, weed killers, marine (copper arsenate) and other paints, ceramics, live stock feed. Lethal Dose: Acute, 200 mg (As20 3); chronic, unknown. How it KiUs: Arsenic is a general protoplasmic poison; it combines with sulfhyd ral (-SH) groups on enzymes to inhibit their normal function. This results in disruption of normal metabolic pathways related to energy transfer. Poison Notes: The trivalent arsenic (As .. 3) is more toxic than thepentava lent (As"s) form. Arsenic is one of the oldest poisons used by humans. IVICTIM OF ARSENIC Administered: Often adrrtinistered to victim in food or drink. Symptom Onset Time Interval: Hours to days. Symptoms-Acute: GI (30 minutes to 2 hours post-exposure): vomiting, bloody diarrhea, severe abdominal pain, burning esophageal pain, metallic taste in the mouth. Later symptoms include: jaundice, kidney failure, and peripheral neuropathies (destruction of the nervous system). Death from circulatory failure within 24 hows to 4 days. Symptoms-Chronic: GI (diarrhea, abdorrtinal pain), skin (hyperpigmen tation of palms and soles), nervous system (symmetrical sensory neur apathy with numbness and loss of vibra tory or positional sense, burning pain on the soles of the feet), localized edema (face, ankles), sore throat, 108 CRIMINAL POISON ING stomatitis, pruritis, cough, tearing, salivation, garlic odor on breath, Aldrich-Mees lines (horizontal white Hnes that normally take 5 to 6weeks to appear after the exposed nail bed area grows), hair loss. -

Lethal Witness

Lethal Witness Andrew Rose Barrister and Author A meeting of the Society was held at the Royal Society of Medicine, 1 Wimpole Street, London W1, on Thursday, 2 April 2009. The President, Dr Robin Moffat, was in the Chair. The President: Hello members and guests. Thank you very much for coming out on Obama day. You haven’t been seduced to the East End of London you have stuck with us here in the West. We are very pleased to welcome tonight a distinguished barrister and a retired Immigration Judge, Andrew Rose, who is an author and he has written a number of books, one of which was nominated for a prize. Most of the matters he has written about have been forensic, have they not? Murder on a Common; is that right? One or two things like that. So we are very pleased to have him here and his address, of course, is entitled Lethal Witness, and the lethal witness is not here tonight, he departed many years ago, and his name was Bernard Spilsbury, a household name in the last century, particularly in the twenties and thirties. Bernard Spilsbury was very well known to everybody who practised or who were students in the twenties and thirties and I always compare him to Hamilton Bailey. These two names: they were very similar men. Hamilton Bailey was a surgeon who smoked three packs a day; I think Spilsbury used to smoke about three packs a day. They both lost their sons in tragic circumstances and they both had what amounted to nervous breakdowns. -

An Invisible Threat?

62656 FSS - 8pp No. 55 27/8/08 10:38 Page 1 NNumberNumberNumberNumber 51 51 5551 J July JulJulyuly - - - S - SS eptSepteptept 2 200820 200700707 ISSIISSSSISSNNN1N133153159539-082095-08-08209-082020 TTTHEHEHEFFFOOORENRENRENSICSICSICSSSCCCIENCEIENCEIENCESSSOOOCIETYCIETYCIETY interinterinterAAAA forum forum forum forum for forfor for forensic forensicforensic forensic scientists scientistsscientists scientistsfff and andand and a associatedacesa saacesssoacesssosociaciaciatedtedted pro professionalspro professifessifessionaonaonalslsls A forum for forensic scientists and associated professionals WWirierelelessssnneetwtwoorkrkiningg--aannininvvisisibibleleththrereaat?t? SSoommeeththoouugghhtstsaannddrereccoommmmeennddaatitoionnss bybyAngusAngusMarshall Marshall As this article was being written, news broke that the American retail network within a few seconds and once an infected machine is re- As this article was being written, news broke that the American retail network within a few seconds and once an infected machine is re- group, TJX Corporation – owner of TJ Maxx, Barnes & Noble and introduced to a corporate or other secure network, the infestation may group, TJX Corporation – owner of TJ Maxx, Barnes & Noble and introduced to a corporate or other secure network, the infestation may several others, had been the victim of an international gang's efforts to continue to spread. several others, had been the victim of an international gang's efforts to continue to spread. acquire personal data held on its computer systems. The gang acquired acquire personal data held on its computer systems. The gang acquired In TJX's case, the attackers managed to gain access to the corporation's credit and debit card details of some 40 million consumers by abusing In TJX's case, the attackers managed to gain access to the corporation's credit and debit card details of some 40 million consumers by abusing wireless network and then implanted software which logged transaction the company's wireless network systems.