International Review of the Red Cross, May 1973, Thirteenth Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Une Miss Belle, Talentueuse Et Engagée ! Sommaire 10 Dimanche 13 Septembre 2020 - N°1696 Mode Et Tendance Du Holographique Dans Vos Dressings

N°1696 SUPPLÉMENT HEBDOMADAIRE DIMANCHE 13 SEPTEMBRE 2020 CULTURE - SOCIÉTÉ - VARIÉTÉS - SPORT CONCOURS MISS TUNISIE 2021 UNE MISS BELLE, TALENTUEUSE ET ENGAGÉE ! SOMMAIRE 10 DIMANCHE 13 SEPTEMBRE 2020 - N°1696 MODE ET TENDANCE DU HOLOGRAPHIQUE DANS VOS DRESSINGS 12 DECO PAPIER PEINT ET SI VOUS AGRANDISSIEZ VOS ESPACES ? EN COUVERTURE CONCOURS MISS TUNISIE 2021 UNE MISS BELLE, 14 TALENTUEUSE 4 ET ENGAGÉE ! Annoncé en décembre 2019, suite à un appel à can- didature, le Concours Miss Tunisie 2021 s’était heurté, quelque peu, aux conditions contraignantes dues à la pandémie du Covid-19. Mme Aïda Antar, organisatrice L’INVITÉ dudit concours, a fi ni par baisser les bras et suspendre JIHED AZAÏEZ, ANCIEN HANDBALLEUR un événement qui lui tient à cœur, et qui représente INTERNATIONAL D’EMS ET DU CA pour elle un challenge bisannuel relevé. «DÉVELOPPER LES ACADÉMIES» PRÉSIDENT-DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL : Nabil GARGABOU A NOS ANNONCEURS Nous informons nos chers clients annonceurs que, DIRECTEUR DE LA RÉDACTION désormais, le dernier délai DES PUBLICATIONS : de dépôt de leurs annonces Supplément distribué Chokri BEN NESSIR dans La Presse- Magazine gratuitement avec le journal La Presse est fi xé au mardi à 13h00. Avec les remerciements RÉDACTEUR EN CHEF : de La Presse-Magazine Jalel MESTIRI RESPONSABLE DE LA RÉDACTION : Samira HAMROUNI EN COUVERTURE CONCOURS MISS TUNISIE 2021 UNE MISS BELLE, TALENTUEUSE ET ENGAGÉE ! Par Dorra BEN SALEM nnoncé en décembre 2019, suite à un appel Miss Tunisia Official », indique Mme Antar. Ainsi ce serait à candidature, le Concours Miss Tunisie aux candidates de se déplacer jusqu’à Tunis pour le 2021 s’était heurté, quelque peu, aux condi- casting, dans l’espoir d’être acceptées et de bénéficier tions contraignantes dues à la pandémie du de la chance de remporter la sublime couronne, digne Covid-19. -

Diplomatic List – Fall 2018

United States Department of State Diplomatic List Fall 2018 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all bilateral missions and delegations (herein after “missions”) and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff of the mission having diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom, or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as an executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -- A diplomatic agent’s family members are entitled to the same immunities unless they are United States Nationals. -

UN Women, the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, with the Support of the United Nations Regional Commissions

Directory of NATIONAL MECHANISMS for Gender Equality July 2013 6 This page is intentionally left blank 7 Directory of NATIONAL MECHANISMS for Gender Equality July 2013 The Directory of National Mechanisms for Gender Equality is maintained by UN Women, the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, with the support of the United Nations Regional Commissions. In order to ensure that the information in the Directory is as comprehensive and accurate as possible, Governments are kindly invited to provide relevant information corrections and/or additions regarding their national machineries to: UN Women United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women New York, NY 10017 Phone: (646) 781-4426 E-mail: [email protected] National Mechanism Country: Name: Address: Telephone: FAX: E-Mail: URL: Head of National Mechanism Name: Title: Appointed by: 8 Secondary data entry form - National mechanisms for gender equality* Country: Name of mechanism: Address: Telephone: FAX: Email: URL: Head of mechanism Name: Title: * For purposes of the Directory, the term ‘national mechanisms for gender equality’ is understood to include those bodies and institutions within different branches of the State (legislative, executive and judicial branches) as well as independent, accountability and advisory bodies that, together, are recognized as ‘national mechanisms for gender equality’ by all stakeholders. They may include, but not be limited to: The national mechanisms for the advancement of women within Government (e.g. a Ministry, Department, or Office. See paragraph 201 of the Beijing Platform for Action) inter-ministerial bodies (e.g. task forces/working groups/commissions or similar arrangements) advisory/consultative bodies, with multi-stakeholder participation gender equality ombud gender equality observatory Parliamentary committee 9 This page is intentionally left blank 10 Afghanistan Women's Affairs Address Park Road Name Mrs. -

Reproductive Rights Are Human Rights

REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS ARE HUMAN RIGHTS A HANDBOOK FOR NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS INSTITUTIONS REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS ARE HUMAN RIGHTS A HANDBOOK FOR NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS INSTITUTIONS NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * Symbols of the United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a figure indicates a reference to a United Nations document. HR/PUB/14/6 © 2014 United Nations All worldwide rights reserved All photographs © UNFPA CONTENTS List of Boxes 7 List of Abbreviations 8 The Role of the United Nations Population Fund 10 The Role of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 10 The Role of the Danish Institute for Human Rights 11 Acknowledgements 11 Preface 12 Introduction 13 Purpose 13 Key Definitions 18 Content 20 1. Promoting the Reproductive Rights Agenda 21 Reproductive Rights are Human Rights 21 Examples of Key Practical Elements of Reproductive Rights 22 Understanding Sexual and Reproductive Health 24 International Commitments – a Historical Overview 24 2. The National Human Rights Institution Mandate 31 Assessing Workplace Policies and Building the Reproductive Rights Competence of Staff 35 Legislative and Administrative Provisions 38 Monitoring and Reporting at the National Level 42 Reproductive Rights: A Tool for Monitoring States’ Obligations 45 Ratification of International Instruments 56 International Reporting 57 Other Forms of International Accountability and Cooperation 60 Human Rights Education and Research 65 Increase Public Awareness 69 Complaints Handling 72 3. -

Diplomatic List

United States Department of State Diplomatic List Spring 2020 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all missions and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are those mission members who have diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom, or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as an executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -- A diplomatic agent’s family members are entitled to the same immunities unless they are United States Nationals. ASTERISKS (*) IDENTIFY UNITED STATES NATIONALS. -

Meteorological Services of the World

\/\(/v) 0 1\ WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION tc-tq ~-- METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES OF THE WORLD SERVICES METEOROLOGIQUES DU MONDE WMO/OMM - N° 2 ORGANISATION METEOROLOGIQUE MONDIALE (--~f ( ") '" ( )- © . World Meteorological Organization Organisation meteorologique mondiale ~ ISBN 92 - 63 - 03002 - 2 I, NOTE The designations employed and the presentation ofmaterial in this publication do not imply the I expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the World Meteorological I Organization concerning the legal status ofany country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation ofits frontiers or boundaries. il Les appellations employees dans cette publication et la presentation des donnees qui y figurent il n'impliquent de la part du Secretariat de l'Organisation meteorologique mondiale aucune prise de position quant au statutjuridique des pays, territoires, villes Oll zones, Oll de leurs autorites, ni quant au I trace de leurs frontieres ou limites. ~.~. C'-'G'd I q;'1v' LI'I'I "," I L_ Supplement/Supplement Inserted by/lnsere par On/Le October/Octobre 1995 'RovNO~ Lt J 1\1\' Cj b October/Octobre 1996 S g~:r c.>/(/'~~'. /1". 11//-/. /;/" .. -I.-~~I?··l/"~ GGtOOeFJGetobre 1997 o" ... c','" October/Octobre 1998 October/Octobre 1999 IT',D' ,S Ir'll .1-r ? ~ 2> c~/ October/Oetobre 2000 2-~. I! (0 U October/Oetobre 2001 J./). J /2./1/ 101 October/Octobre 2002 'u-}) 'S 8/10/OZ October/Octobre 2003 IT<D -S =;-/III{)] October/Octobre 2004 I INTRODUCTION This publication is issued in a composite form from the language viewpoint, i.e., the information is given in either English or French according to the language in which the inform ation has- been supplied to the Secretariat by the respective countries. -

Measuring Capital Flight: Estimates and Interpretations

Working Paper 194 Measuring Capital Flight: Estimates and Interpretations Benu Schneider March 2003 Overseas Development Institute 111 Westminster Bridge Road London SE1 7JD UK Acknowledgements This paper is the first part of a project on Capital Flight from Developing Countries. The project is funded by ESCOR, Department for International Development, UK and we gratefully acknowledge their financial support. The UK Department for International Development (DFID) supports policies, programmes and projects to promote international development. DFID provided funds for this study as part of that objective but the views and opinions expressed are those of the author alone. The author would like to thank Mathieu Sampson and Benno Ferrarini for their research assistance. ISBN 0 85003 633 X © Overseas Development Institute 2002 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. ii Contents Acknowledgements ii Tables and Figures v Abstract vi 1 Introduction 1 2 Defining capital flight 3 2.1 Preferred definition 3 2.2 An overview of definitions of capital flight in the literature 3 2.3 The broad definition of capital flight 4 2.4 Capital flight defined as a response to discriminatory treatment of domestic capital 5 2.5 Defining capital flight as an illegal transaction 6 3 Methods to measure capital flight 8 3.1 Broad measure of capital flight -

NPPES Data Dissemination - Code Values July 2011 I

National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (NPPES) Data Dissemination – Code Values Prepared For Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Updated: July 2011 Effective Date: October 30, 2011 This page intentionally left blank. NPPES Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................... i List of Exhibits ............................................................................................................................. ii 1 NPPES Code Table Values ................................................................................................1 1.1 Entity Type Codes ........................................................................................................1 1.2 Sole Proprietor Codes ..................................................................................................1 1.3 Subpart Codes .............................................................................................................1 1.4 Gender Codes ..............................................................................................................2 1.5 Deactivation Reason Codes ......................................................................................... 2 1.6 Other Provider Name Type Codes ................................................................................ 3 1.7 Name Prefix Codes ......................................................................................................3 1.8 Name Suffix -

In the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts

Case 1:20-cv-10015-DJC Document 29 Filed 07/08/20 Page 1 of 78 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS EQUAL MEANS EQUAL, THE YELLOW ROSES, KATHERINE WEITBRECHT, Plaintiffs, v. Civil Action No. 20-cv-10015-DJC DAVID S. FERRIERO, in his official Capacity as Archivist of the United States, Defendant. ______________________________________________________________________ AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS The United States Conference of Mayors Equal Means ERA 38 Agree for Georgia LARatifyERA Jodi Siegel* Kristine L. Roberts Chelsea Dunn* Mass. BBO No. 651491 *Pro Hac Vice forthcoming SOUTHERN LEGAL COUNSEL, INC. BAKER, DONELSON, 1229 NW 12th Avenue BEARMAN, CALDWELL & Gainesville, FL 32601 BERKOWITZ, P.C. (305) 271-8890 165 Madison Avenue [email protected] First Tennessee Building [email protected] Suite 2000 Washington, D.C. 20001 (901) 526-2000 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae Case 1:20-cv-10015-DJC Document 29 Filed 07/08/20 Page 2 of 78 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTERESTS OF THE AMICI ........................................................................................... 1 ARGUMENT .................................................................................................................... 3 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 3 II. WITH THE RATIFICATION OF THE ERA, THE U.S. JOINS OTHER NATIONS IN GUARANTEEING EQUALITY FOR WOMEN ..................... 3 III. SEX DISCRIMINATION MAY BE -

General Assembly Distr.: General 3 April 2019

United Nations A/CONF.231/INF/2 General Assembly Distr.: General 3 April 2019 Original: English/French/Spanish Intergovernmental Conference to Adopt the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration Marrakech (10–11 December 2018) List of Delegations to the Intergovernmental Conference to Adopt the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration 19-05600 (E) 100419 *1905600* A/CONF.231/INF/2 I. States AFGHANISTAN H.E. Ms. Alema, Deputy Minister of Refugees and Repatriations Representatives Mr. David Jawad Majed, Assistant Mr. Barekzai Barialai, National Security Council Officer ALBANIA H.E. Mr. Ilir Meta, President Representatives Mrs. Artemis Dralo, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Mr. Arben Cici, Chief of Staff Mr. Ilir Kulla, Advisor Mrs. Ilda Zhulali, Advisor Mr. Bujar Bala, Diplomat, Mission of Albania in Geneva Mr. Leart Gjoka, Assistant, Mr. Gerald Gjogjini, Camera person ALGERIA H.E. Mr. Noureddine Bedoui, Minister of Interior and Local Governments Representatives H.E. Mr. Djamel Eddine Grine, Ambassador Counsellor, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Mr. Hassen Kassimi, Director, Ministry of Interior Mr. Mohammed Zergot, Deputy director, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Mr. Ahmed Benyamina, Ambassador of Algeria to the Kingdom of Morocco Mr. Abdellatif Djouder Mahmoud, Director, Ministry of Justice Mr. Ahmed Benyahya, Secretary of Foreign Affairs at the Algerian Embassy in the Kingdom of Morocco ANDORRA H.E. Ms. Elisenda Vives, Permanent Representative of Andorra to the United Nations Representative Ms. Nahia Roche, Desk Officer for Multilateral Affairs and Cooperation, Ministry of Foreign Affairs ANGOLA H.E. Mr. Angelo de Barros da Veiga Tavares, Minister of Interior Representatives H.E. Mr. -

AU Data Standards Manual (PDF)

► At Alfred University DATA STANDARDS DOCUMENT FOR ALL ALFRED UNIVERSITY BANNER SYSTEMS TABLE OF CONTENTS ALFRED UNIVERSITY DATA STANDARDS GENERAL ..............................................................................................................................................4 CONFIDENTIAL RECORDS ……………………………………………….....................................................4 Confidentiality Indicator ......................................................................................................4 Releasing Confidential Information..................................................................................5 DATA MAINTENANCE RESPONSIBIITIES BY FUNCTIONAL AREAS ..........................................5 SEARCH PROCEDURES ....................................................................................................................6 NAME STANDARDS ...........................................................................................................................12 Last Name .............................................................................................................................12 First Name ............................................................................................................................12 Preferred First Name ..........................................................................................................13 Middle Name or Initial ........................................................................................................13 Name Change .......................................................................................................................14 -

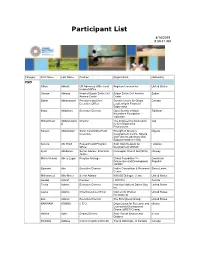

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana