Growing the “Garbage of Eden”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewel Skyline

experience A newsletter of the Singapore Cooperation Programme July - September 2012 ISSUE 44 JEWEL in the SKYLINE MEGA PARK GARDENS BY THE BAY IS A FANTASY IN BLOOM GREEN WITH A PURPOSE THE MAKEOVER OF SINGAPORE’S PARKS REBUILDING A COMMUNITY A HELPING HAND FOR PAKISTAN’S FLOOD VICTIMS FOREWORD QUOTES FROM READERS’ LETTERS n our last issue of Experience Singapore, we revealed Singapore’s plans to “Thank you for the April-June issue of Experience Singapore. I collect all the issues transform from a “Garden City” to a “City in A Garden”. We provide more details that you send me. Any latest news of in this issue. Our cover story Jewel Of A Park is dedicated to Singapore’s new Singapore never fails to impress me. When I Gardens By The Bay which was offi cially opened by Prime Minister Lee Hsien saw the latest cover, my mind went back to ILoong on 28 June 2012. The Gardens, which took 8 years to complete, are set to the Chinese cultural centre in Chinatown – it become an intrinsic part of Singapore’s new downtown. was one of the most striking places I visited in Singapore four years ago.” Outside of the city, the rejuvenation of our community parks is also well underway. In Beautifying With A Purpose, fi nd out how a utilitarian canal in Premachanda Abeywickrama Danapala, Sri Lanka Bishan-Ang Mo Kio park was transformed into a beautiful waterway employing natural bioengineering techniques to keep the water clean. This issue also explores how Singapore NGO Mercy Relief recently completed a “After my wonderful experience in Singapore, project to reconstruct homes for the people in the village of Wazir Ali Jat in Pakistan, where I had the opportunity to participate in the SCP course ‘Enhancing Pedagogy Skills For who were displaced in the nation’s worst-ever fl ood. -

Living Water

LIVING WITH WATER: LIVING WITH WATER: LESSONS FROM SINGAPORE AND ROTTERDAM Living with Water: Lessons from Singapore and Rotterdam documents the journey of two unique cities, Singapore and Rotterdam—one with too little water, and the other with too LESSONS FROM SINGAPORE AND ROTTERDAM LESSONS much water—in adapting to future climate change impacts. While the WITH social, cultural, and physical nature of these cities could not be more different, Living with Water: Lessons from Singapore and Rotterdam LIVING captures key principles, insights and innovative solutions that threads through their respective adaptation WATER: strategies as they build for an LESSONS FROM uncertain future of sea level rise and intense rainfall. SINGAPORE AND ROTTERDAM LIVING WITH WATER: LESSONS FROM SINGAPORE AND ROTTERDAM CONTENTS About the organisations: v • About the Centre for Liveable Cities v • About the Rotterdam Office of Climate Adaptation v Foreword by Minister for National Development, Singapore vi Foreword by Mayor of Rotterdam viii Preface by the Executive Director, Centre for Liveable Cities x For product information, please contact 1. Introduction 1 +65 66459576 1.1. Global challenges, common solutions 1 Centre for Liveable Cities 1.2. Distilling and sharing knowledge on climate-adaptive cities 6 45 Maxwell Road #07-01 The URA Centre 2. Living with Water: Rotterdam and Singapore 9 Singapore 069118 2.1. Rotterdam’s vision 9 [email protected] 2.1.1. Rotterdam’s approach: Too Much Water 9 2.1.2. Learning to live with more water 20 Cover photo: 2.2. A climate-resilient Singapore 22 Rotterdam (Rotterdam Office of Climate Adaptation) and “Far East Organisation Children’s Garden” flickr photo by chooyutshing 2.2.1. -

Waste Minimization & Recycling in Singapore

2016 World Waste to Energy City Summit Sustainable Singapore – Waste Management and Waste-to-Energy in a global city 11 May 2016 Kan Kok Wah Chief Engineer Waste & Resource Management Department National Environment Agency Singapore Outline 1. Singapore’s Solid Waste Management System 2. Key Challenges & Opportunities 3. Waste-to-Energy (WTE) and Resource Recovery 4. Next Generation WTE plants 2 Singapore Country and a City-State Small Land Area 719.1 km2 Dense Urban Setting 5.54 mil population Limited Natural Resources 3 From Past to Present From Direct landfilling From 1st waste-to-energy plant Ulu Pandan (1979) Lim Chu Kang Choa Chu Kang Tuas (1986) Tuas South (2000) Lorong Halus …to Offshore landfill Senoko (1992) Keppel Seghers (2009) 4 Overview of Solid Waste Management System Non-Incinerable Waste Collection Landfill 516 t/d Domestic Total Waste Generated 21,023 t/d Residential Trade 2% Incinerable Waste Recyclable Waste 7,886 t/d 12,621 t/d 38% 60% Ash 1,766 t/d Reduce Reuse Total Recycled Waste 12,739 t/d Metals Recovered 61% 118 t/d Industries Businesses Recycling Waste-to-Energy Non-Domestic Electricity 2,702 MWh/d 2015 figures 5 5 Key Challenges – Waste Growth and Land Scarcity Singapore’s waste generation increased about 7 folds over the past 40 years Index At this rate of waste growth… 4.00 New waste-to-energy GDP 7-10 years 3.00 Current Population: 5.54 mil Land Area: 719 km2 Semakau Landfill Population Density : 7,705 per km2 ~2035 2.00 Population 30-35 years New offshore landfill 1.00 Waste Disposal 8,402 tonnes/day (2015) -

Singapore Raptor Report February 2020

Singapore Raptor Report February 2020 Common Buzzard, juvenile pale morph, at Bedok North Avenue 3, on 27 Feb 2020, by Danny Khoo Summary for migrant species: In February 2020, 126 raptors of 10 migrant species were recorded. A scarce Common Buzzard perched on top of a HDB apartment block at Bedok North Avenue 3 was photographed by Danny Khoo on the 27th. A single dark morph Booted Eagle was photographed in flight at Coney Island on the 23rd by Yip Jen Wei, who also photographed a Grey-faced Buzzard at Puaka Hill, Pulau Ubin on the 29th. Three Chinese Sparrowhawks were recorded, one at Pasir Ris, one at Lorong Halus – Coney Island area, and one female wintering at Ang Mo Kio. Of the six Jerdon's Bazas, five were recorded in the Lorong Halus – Coney Island area between the 7th to the 22nd, and one at Pulau Ubin on the 23rd. At our coastal areas, six Western Ospreys were recorded, including one at Lorong Halus on the 25th, mobbed by a Peregrine Falcon. As for the Peregrine Falcons, seven were recorded around the island, including one that mobbed an Oriental Honey Buzzard at Lorong Halus on the 25th. Page 1 of 9 Nine Japanese Sparrowhawks were recorded, all singles, at various localities. Rounding off the migrant raptors were 45 Oriental Honey Buzzards and 47 Black Bazas, including a flock of 14 at Kranji Marshes on the 28th. Grey-headed Fish Eagle, flying off with a Cinnamon Bittern that it had caught in the river, at Pandan River, on 18 Feb 2020, by Yeak Hwee Lee. -

Building an Offshore Nature Haven on Trash

CASE STUDY Building an Offshore Nature Haven on Trash Landfills are associated with toxic environments, yet the offshore landfill in Singapore has thriving marine life that people come to explore during low tides. Photo credit: Ria Tan. Singapore built an offshore landfill on Pulau Semakau primarily for waste management, but it also ensured that marine life would thrive and it could serve as a public park. Published: 27 November 2017 Overview As a fast-growing island city-state, Singapore has little space on its mainland for the rubbish its residents generate. Its innovative solution was to build one of the world’s earliest and cleanest offshore landfills—an island that today harbours flourishing ecosystems from mangroves to coral reefs. This case study was adapted from Urban Solutions of the Centre for Liveable Cities in Singapore. Challenges In 1992, one of Singapore’s last two landfill sites, a dumping ground at Lim Chu Kang in the north western region of the mainland, reached its maximum capacity and was closed. The other landfill, a 234- hectare site at Lorong Halus in the northeast, was expected to fill up by 1999. Singapore, like any small country or city with a burgeoning economy, faced a trash problem. As it grew, it generated increasing amounts of waste. In 1970, about 1,300 tonnes of solid waste was disposed of each day; by 1992, this had ballooned to about 6,000 tonnes a day. This was despite the fact that Singapore had been incinerating its trash since the late 1970s to generate energy and minimise the land required for dumps. -

One Party Dominance Survival: the Case of Singapore and Taiwan

One Party Dominance Survival: The Case of Singapore and Taiwan DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lan Hu Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor R. William Liddle Professor Jeremy Wallace Professor Marcus Kurtz Copyrighted by Lan Hu 2011 Abstract Can a one-party-dominant authoritarian regime survive in a modernized society? Why is it that some survive while others fail? Singapore and Taiwan provide comparable cases to partially explain this puzzle. Both countries share many similar cultural and developmental backgrounds. One-party dominance in Taiwan failed in the 1980s when Taiwan became modern. But in Singapore, the one-party regime survived the opposition’s challenges in the 1960s and has remained stable since then. There are few comparative studies of these two countries. Through empirical studies of the two cases, I conclude that regime structure, i.e., clientelistic versus professional structure, affects the chances of authoritarian survival after the society becomes modern. This conclusion is derived from a two-country comparative study. Further research is necessary to test if the same conclusion can be applied to other cases. This research contributes to the understanding of one-party-dominant regimes in modernizing societies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the Lord, Jesus Christ. “Counsel and sound judgment are mine; I have insight, I have power. By Me kings reign and rulers issue decrees that are just; by Me princes govern, and nobles—all who rule on earth.” Proverbs 8:14-16 iii Acknowledgments I thank my committee members Professor R. -

Presentation

Frasers Centrepoint Trust Proposed Acquisition of Approximately 63.11% Remaining Interest in a Portfolio of 5 Retail Malls and 1 Office Property & Proposed Divestment of Bedok Point 3 September 2020 This presentation shall be read in conjunction with Frasers Centrepoint Trust’s (“FCT”) announcement “(I) THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION OF APPROXIMATELY 63.11% OF THE TOTAL ISSUED SHARE CAPITAL OF ASIARETAIL FUND LIMITED; AND (II) THE PROPOSED DIVESTMENT OF A LEASEHOLD INTEREST IN THE WHOLE OF THE LAND LOTS 4710W, 4711V, 10529L AND 10530N ALL OF MUKIM 27 TOGETHER WITH THE BUILDING ERECTED THEREON, SITUATED AT 799 NEW UPPER CHANGI ROAD, SINGAPORE 467351, CURRENTLY KNOWN AS BEDOK POINT” released on 3 September 2020 and “CIRCULAR TO UNITHOLDERS IN RELATION TO: (1) THE PROPOSED ARF TRANSACTION; (2) THE PROPOSED EQUITY FUND RAISING; (3) THE PROPOSED ISSUE AND PLACEMENT OF NEW UNITS TO THE SPONSOR GROUP UNDER THE PRIVATE PLACEMENT; (4) THE PROPOSED WHITEWASH RESOLUTION; AND (5) THE PROPOSED BEDOK POINT DIVESTMENT” dated 3 September 2020. This presentation may contain forward-looking statements that involve assumptions, risks and uncertainties. Such forward-looking statements are based on certain assumptions and expectations of future events regarding FCT's present and future business strategies and the environment in which FCT will operate, and must be read together with those assumptions. Although the Manager believes that such forward-looking statements are based on reasonable assumptions, it can give no assurance that these assumptions and expectations are accurate, projections will be achieved, or that such expectations will be met. Actual future performance, outcomes and results may differ materially from those expressed in forward-looking statements as a result of a number of risks, uncertainties and assumptions. -

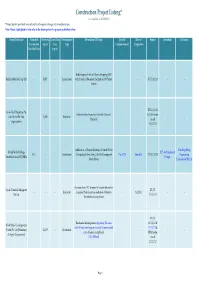

Construction Project Listing* (Last Updated on 20/12/2013) *Project Details Provided May Subject to Subsequent Changes by Owner/Developer

Construction Project Listing* (Last Updated on 20/12/2013) *Project details provided may subject to subsequent changes by owner/developer. Note: Words highlighted in blue refer to the latest updates for projects published before. Owner/Developer Estimated Site Area Gross Floor Development Description Of Project Date Of Date of Source Consultant Contractor Construction (sq m) Area Type Commencement Completion Cost ($million) (sq m) Redevelopment into a 6 Storey Shopping Mall Raffles Medical Group Ltd - 5,827 - Institutional with 2 levels of Basement Carpark at 100 Taman - - ST 17/12/13 - - Warna BT 11/12/13 Grow-Tech Properties Pte Industrial development at Gambas Crescent & URA tender Ltd (Part of Far East - 14,302 - Industrial -- -- (Parcel 3) result Organization) 13/12/13 Addition of a 5 Storey Building to United World Kim Seng Heng United World College BLT Architecture & 42.5 - - Institutional College South East Asia (UWCSEA) campus at Dec-2013 Aug-2015 BT 13/12/13 Engineering South East Asia (UWCSEA) Design Dover Road Construction Pte Ltd Erection of an LPG Terminal to import alternative Vopak Terminals Singapore BT/ST - - - Industrial Liquefied Petroleum Gas feedstock at Banyan - 1Q 2016 -- Pte Ltd 11/12/13 Terminal in Jurong Island BT/ST Residential development comprising 281 units 16/11/12 & World Class Developments with 24 hour concierge service and 18 commercial 11/12/13 & (North) Pte Ltd [Subsidiary - 10,170 - Residential -- -- units at Jalan Jurong Kechil URA tender of Aspial Corporation] (The Hillford) result 22/11/12 Page 1 Construction Project Listing* (Last Updated on 20/12/2013) *Project details provided may subject to subsequent changes by owner/developer. -

Download Tampines Heritage Trail

SUGGESTED SHORT TRAIL ROUTES First recorded in an 1828 map as “R. Tampenus”, Tampines has grown from a once rural locale into an award-winning residential town over the last two centuries. The historical transformation of Tampines can be seen in the maps, images and community stories currently on display at Our Tampines Gallery in Tampines Regional Library. In addition to the gallery, the National Heritage Board has also curated three thematic trails for visitors to explore the unique history and cultural heritage of Tampines. Tampines Town Trail (1.5 hours; bus and walk) Religious Institutions Trail (1.5 hours; bus and walk) Green Spaces Trail (1 hour; on bicycle) Conferred the World Habitat Award in 1991, the development of Tampines is home to many religious institutions that speak of the Tampines is home to a number of parks and green spaces, including Tampines Town was a significant achievement in Singapore’s public diversity of its community. Some of the places of worship featured in some of which were former industrial sites. This cycling trail takes you housing. This trail explores some of the town planning innovations this trail have been in Tampines for more than a century and reflect the through a few scenic locales including a converted quarry, sites where introduced by the Housing & Development Board (HDB) as well as town’s rich cultural heritage. This trail allows visitors to discover these some of Tampines’ former kampongs were once located, as well as sites of everyday heritage that are part and parcel of the Tampines houses of faith, and explore the unique architecture and practices that Lorong Halus, a former landfill turned wetland. -

Current Status of Mangrove Forests in Singapore

Proceedings of Nature Society, Singapore’s Conference on ‘Nature Conservation for a Sustainable Singapore’ – 16th October 2011. Pg. 99–120. THE CURRENT STATUS OF MANGROVE FORESTS IN SINGAPORE YANG Shufen1, Rachel L. F. LIM1, SHEUE Chiou-Rong2 & Jean W. H. YONG3,4* 1National Biodiversity Centre, National Parks Board, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569. 2Department of Life Sciences, National Chung Hsing University, 250, Kuo Kuang Rd., Taichung 402, Taiwan. 3Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA. 4Singapore University of Technology and Design, 20 Dover Drive, Singapore 138682. (*E-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT Even in a small and urbanised country like Singapore, we are still able to find new plant records in our remaining 735 ha of mangrove forests. With only one notable extinction (Brownlowia argentata Kurz), a total of 35 ‘true’ mangrove species can still be found in Singapore. This is half of the world’s total ‘true’ mangrove species recognised by IUCN. The botanical results indicate that Singapore still harbours rich mangrove diversity. The IUCN 'Critically Endangered' mangrove, Bruguiera hainesii C. G. Rogers, was discovered in 2003 as a new record. Thought to be extinct, B. sexangula (Lour.) Poir. trees were re-discovered in 2002 and occur mainly in the back mangrove. In 1999, an uncertain taxon of Ceriops was discovered, and identified as the so-called C. decandra (Griff.) Ding Hou. We later confirmed that the uncertain Ceriops species should be C. zippeliana Blume. Through international collaborative research efforts, the elucidation of the taxonomic identity of Kandelia obovata Sheue, Liu & Yong (the main mangrove of China, Japan, Taiwan and Vietnam) in 2003 was assisted by our local research efforts towards protecting our own Kandelia candel (L.) Druce. -

Waste Minimization & Recycling in Singapore

World Waste to Energy City Summit City Resilience: Integrating Demand-side Solutions into Today’s Cities Singapore’s Integrated Waste Management System Ong Soo San Director Waste & Resource Management Department National Environment Agency Singapore Outline 1. Singapore’s Solid Waste Management Story 2. Overview of Current System 3. Key Challenges & Opportunities 4. Waste-to-Energy (WTE) and Resource Recovery 5. Next Generation WTE Facility 2 From Past to Present FromTransformationDirect landfilling From…and1st waste refuse-to collection-energy plant Of living conditions Ulu Pandan (1979) Lim ChuTransformation KangChinatownChoa Chu Kang of the FromSingapore illegal River street hawkers Tuas (1986) Tuas South (2000) to Lorongal Halusfresco …to Offshore landfill Senoko (1992) Keppel Seghers (2009) 3 Overview of our Waste Management System Consumers Collection 2% Landfill Commercial & Residential Waste Generated Non-Incinerable Waste Retails 20,588 t/d 468 t/d Reduce Ash 1,995 t/d Reuse 60% Waste Recycled 12,250 t/d 38% Incinerable Waste Factories & 7,870 t/d Industries Electricity–2,690 MWh/d Producers Recycle 2014 figures Sustainable Singapore Blueprint 2015 (http://www.mewr.gov.sg/ssb/) • Towards “A Zero Waste Nation” • Achieve 70% overall recycling rate by 2030 4 Singapore Hot & Humid Climate Area : 718.3 sq km Population : 5.47 million Key Challenge : Scarcity of Land 5 Key Challenges – Waste Growth and Land Scarcity Singapore’s waste generation increased about 7 folds over the past 40 years Index At this rate of waste growth… 4.00 New -

Student's Learning Trail Booklet (Secondary)

Contents Come and Discover Sengkang Floating Wetland 1 Treasures on the Trail 2 On a Photo Hunt 3 Our Water Story 4 Punggol Reservoir - Past and Present 5 The Punggol-Serangoon Reservoir Scheme 5 Transformation from Punggol River to Punggol Reservoir 6 The Water Cycle and Journey of Water from Punggol Reservoir 7 ABC Waters Design Features 8 Water Quality Testing 10 Singapore’s Largest Man-made Floating Wetland 12 Life around the Floating Wetland - Wetland Plants 14 Mangrove Plants 15 Animals 16 Keeping Punggol Reservoir Active, Beautiful and Clean 18 Your Reflections 20 Problem-based Activity 22 NEWater Visitor Centre 23 Marina Barrage 24 Copyright © PUB, Singapore’s national water agency 2011. Revised 2017. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publishers. For more information, please visit us at www.pub.gov.sg/getinvolved. Come and Discover Floating Wetland Come join us on the Active, Beautiful, Clean Waters (ABC Waters) Learning Trail @ Sengkang Floating Wetland in Punggol Reservoir, and discover more about the Singapore Water Story. Discover how our small city-state which used to face huge challenges such as droughts and pollution has transformed into a global hydrohub and vibrant City of Gardens and Water. Water sustainability is crucial to Singapore’s success. Singapore has ensured a robust and sustainable water supply capable of catering to the country’s continued growth through the Four National Taps.