Geographies of (In)Equalities: Space and Sexual Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

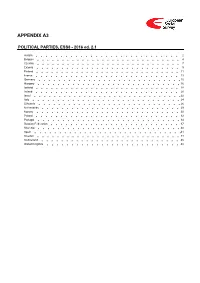

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Portugal a Nearshore Outsourcing Destination

PORTUGAL a nearshore outsourcing destination Research Report Lisbon, October, 2010 ABOUT APO The non-profit organisation “Portugal Outsourcing”, founded in 2008, is one of the top IT and BPO companies in Portugal that holds over 85% of the national market share. APO1 aims to contribute to the Portuguese outsourcing market development, especially in IT Outsourcing and IT enabled BP Outsourcing services. This objective will be achieved by promoting best practices, building and implementing practice codes, stimulating Industry-University relationships, gathering and analysing data and other relevant information, in order to make sourcing managers and market analysts aware of Portugal’s skills, competences and other capabilities, as a potential location for outsourcing services in a nearshore basis. APO will work concomitantly with other private and public institutions prompting the discussion of relevant issues for the sector evolution in order to identify gaps in competiveness and help to define specific actions to bridge those gaps. Portsourcing - Associação das Empresas de Outsourcing de Portugal Rua Pedro Nunes, Nº 11 - 1º, 1050 - 169 Lisboa - Portugal Tel. (+351) 213 958 615 | Mobile: (+351) 926 621 975 www.portugaloutsourcing.pt This report was based on information obtained from several sources deemed as accurate and reliable by entities that have made use of them. No cross- check of information has been performed by the Associação Portugal Outsourcing for the production of the current report. Updates of this report may be carried out by the Associação Portugal Outsourcing in the future; any different perspectives and analysis from those expressed in this report may be produced. This report cannot be copied, reproduced, distributed or made available in any way. -

Internal Politics and Views on Brexit

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8362, 2 May 2019 The EU27: Internal Politics By Stefano Fella, Vaughne Miller, Nigel Walker and Views on Brexit Contents: 1. Austria 2. Belgium 3. Bulgaria 4. Croatia 5. Cyprus 6. Czech Republic 7. Denmark 8. Estonia 9. Finland 10. France 11. Germany 12. Greece 13. Hungary 14. Ireland 15. Italy 16. Latvia 17. Lithuania 18. Luxembourg 19. Malta 20. Netherlands 21. Poland 22. Portugal 23. Romania 24. Slovakia 25. Slovenia 26. Spain 27. Sweden www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The EU27: Internal Politics and Views on Brexit Contents Summary 6 1. Austria 13 1.1 Key Facts 13 1.2 Background 14 1.3 Current Government and Recent Political Developments 15 1.4 Views on Brexit 17 2. Belgium 25 2.1 Key Facts 25 2.2 Background 25 2.3 Current Government and recent political developments 26 2.4 Views on Brexit 28 3. Bulgaria 32 3.1 Key Facts 32 3.2 Background 32 3.3 Current Government and recent political developments 33 3.4 Views on Brexit 35 4. Croatia 37 4.1 Key Facts 37 4.2 Background 37 4.3 Current Government and recent political developments 38 4.4 Views on Brexit 39 5. Cyprus 42 5.1 Key Facts 42 5.2 Background 42 5.3 Current Government and recent political developments 43 5.4 Views on Brexit 45 6. Czech Republic 49 6.1 Key Facts 49 6.2 Background 49 6.3 Current Government and recent political developments 50 6.4 Views on Brexit 53 7. -

Social Democratic Parties and Trade Unions: Parting Ways Or Facing the Same Challenges?

Social Democratic Parties and Trade Unions: Parting Ways or Facing the Same Challenges? Silja Häusermann, Nadja Mosimann University of Zurich January 2020, draft Abstract Both social democratic parties and trade unions in Western Europe have originated from the socio-structural emergence, political mobilization and institutional stabilization of the class cleavage. Together, they have been decisive proponents and allies for the development of so- cial, economic and political rights over the past century. However, parties of the social demo- cratic left have changed profoundly over the past 30 years with regard to their membership composition and – relatedly – their programmatic supply. Most of these parties are still strug- gling to decide on a strategic-programmatic orientation to opt for in the 21st century, both regarding the socio-economic policies they put to the forefront of their programs, as well as regarding the socio-cultural stances they take (and the relative weight of these policies). Since their strategic calculations depend, among others things, on the coalitional options they face when advancing core political claims, we ask if trade unions are still "natural" allies of social democratic parties or if they increasingly part ways both regarding the socio-demographic composition of constituencies as well as the political demands of these constituencies. We study this question with micro-level data on membership composition from the Euroba- rometer and the European Social Survey from 1989 to 2014 as well as data on policy prefer- ences from the European Social Survey from 2016 while focusing on the well-known welfare regimes when presenting and discussing the results. -

Page 01 July 10.Indd

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com BUSINESS | 17 SPORT | 22 Global economy Serena soars to ‘grim’ and G20 seventh heaven at must fix it: China Wimbledon SUNDAY 10 JULY 2016 • 5 SHAWWAL 1437 • Volume 21 • Number 6853 thepeninsulaqatar @peninsulaqatar @peninsula_qatar Eid fervour continues Mercury likely to 182,000 from hit 47 degrees until Tuesday Qatar visited The Peninsula DOHA: The Qatar Meteorology Dubai last year Department has forecast rise in temperature by three to four degree Celsius above average and strong winds with dust at places 32 percent year on year to just shy across the country over three days of 182,000 in 2015,” Issam Abdul starting from today. This upward trend Rahim Kazim, CEO, Dubai Corpo- Due to the extension of Indian has continued in ration for Tourism Marketing and monsoon seasonal low over the Commerce, told The Peninsula. region, fresh to strong northwest- 2016, with a 26 “This upward trend has contin- erly wind is expected to affect percent spike in ued in 2016, with a 26 percent spike most areas of the country during visitor volumes in the in visitor volumes in the first quar- the day until Tuesday, the depart- ter of the year,” he added. ment said in a statement. first quarter of the There are multiple reasons for The wind speed will range year. Dubai being one of the most pre- between 18 and 28 knots, gusting ferred destinations for the people to 38 sometimes over some areas, of Qatar. blowing dust and reducing visibil- Compared to other countries, ity to 2km or less in some areas. -

Beyond Austerity

Imposed cover:Layout 1 16/03/2016 11:03 Page 1 BEYOND AUSTERITY Beyond Austerity argues that the European Union already has the means to finance the equivalent of the Roosevelt BEYOND New Deal, which saved the US from Depression in the 1930s, without needing either fiscal federalism or ‘ever AUSTERITY closer union’. This is highly relevant to the referendum on British membership of the EU. How can Europe’s economic recovery be accomplished? The European Investment Bank Democratic Alternatives and the European Investment Fund can issue Eurobonds that for do not count on the debt of EU member states, nor need national guarantees, nor require fiscal transfers between Europe Germany and Greece or any other countries. Heads of state and government in the European Council have the right to define ‘general economic policies’ that the European Central Bank is obliged to support. The European Commission has by displaced this important capacity, although the structure for European recovery was carefully assembled by Jacques Delors, its former President, in conjunction with the author S STUART HOLLAND during the 1990s. Another Europe is possible. Who will TUART make the first move beyond austerity and start to put Europe back to work? H OLLAND £8.95 SPOKESMAN www.spokesmanbooks.com Holland Book:Layout 1 16/03/2016 09:02 Page 1 ???????????? 1 Beyond Austerity – Democratic Alternatives for Europe Stuart Holland SPOKESMAN Holland Book:Layout 1 16/03/2016 09:02 Page 2 2 ???????????? First published in 2016 by Spokesman Russell House Bulwell Lane Nottingham NG6 0BT England Phone 0115 9708318 Fax 0115 9420433 www.spokesmanbooks.com Copyright © Stuart Holland All rights reserved. -

S Left Bloc Puts Socialist Party on the Spot

Surge in Portugal’s Left Bloc Puts Socialist Party on the Spot By Dick Nichols Global Research, October 27, 2015 Socialist Project 27 October 2015 Will Portugal finally see the end of austerity as administered for four years by the right-wing coalition (known as Portugal Ahead) composed of the Social-Democratic Party (PSD) and Democratic and Social Centre-People’s Party (CDS-PP)? In the country’s legislative October 4 elections this governing alliance, running for the first time as a single ticket called Portugal Ahead (except on the Azores), won the elections, but with only 38.4 per cent of the vote (down from 50.4 per cent at the 2011 national election). Of the 5.4 million Portuguese who voted, 739,000 turned their back on the outgoing government, leaving it with only 107 seats in the 230-seat parliament (down 25). As a result, the PSD-CSD alliance, which boasted during the election campaign of being the most reliable tool of the Troika (European Commission, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund), could even lose government. Some of the votes lost to the right would have joined the ranks of the 4.27 million abstaining (an increase of 238,000 in a country of 9.68 million voters): this 44.1 per cent abstention rate was the highest since the 1974 Carnation Revolution overthrew the dictatorship of António Salazar and his successor Marcelo Caetano. A lot would have gone to the Socialist Party (PS), which governed the country from 2005 until 2011. However, the total PS vote increased by only 4.3 per cent, from 28 per cent to 32.3 per cent (180,000 votes extra), giving it 86 seats (12 more). -

European Integration and the Vote in EP Elections in Times of Crisis

European Integration and the Vote in EP Elections in Times of Crisis Ilke TOYGÜR Autonomous University of Madrid Abstract: Do ideas related to European integration influence vote choice in European Parliament elections in times of crisis? Economic crisis, bailout packages, and austerity measures have been the central agenda in Southern European countries for the last few years, and the strong, subsequent decline of trust in European and national institutions has been alarming. Citizens’ dealignment and realignment proved itself important in various demonstrations around Europe. This situation led citizens to cast votes for new political parties, and decreasing the vote share of older mainstream ones. Political scientists have a vivid interest in this topic, and there is an ever-growing literature available on the effects of economic crisis on elections. Voters, as well as political parties, have received a great deal of academic attention. Southern European countries have faced similar implementations of the crisis and congruent regulations from the European Union. However, there are different implications for their party system change and voting behaviour in these countries. Based on the European Election Studies (EES) data for the last three European Parliament elections of 2004, 2009 and 2014 this paper, however, does not find any major traces of EU issue voting. Key Words: European integration, voting behaviour, issue voting, crisis, Southern Europe Draft version, comments are very welcomed! Paper prepared for presentation at the EES 2014 Conference, November 6-8, 2015, MZES, University of Mannheim. Introduction The global economic and financial crisis and its implications have received a lot of attention in political science research over the last few years. -

PORTUGAL Your Place in Europe

PORTUGAL your place in Europe CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1) GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT PORTUGAL 1.1 Country ID 1.2 European Union and Location within Europe 1.3 World Strategic Location 1.4 Political and Social environment 1.4.1 Government Stability 1.4.2 Quality of life 2) COMPETITIVENESS 2.1 Market and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) 2.1.1 Economic Key Performance Indicators 2.1.2 Market segments recently installed in Portugal and FDI 2.1.3 Financial sector in Portugal 2.1.3.1 Domestic Banking System 2.1.3.2 Portugal as a destination for Financial Services back-offices 2.1.4 Doing Business in Portugal 2.2 Infrastructures 2.2.1 Roads 2.2.2 Railroad Infrastructure 2.2.3 Seaports 2.2.4 International Airports 2.3 Technology and Innovation 2.3.1 Technology 2.3.2 Innovation 2.4 Human Resources and labour Market 2.4.1 Education and talent 2.4.2 Labour Costs 2.4.3 Financial and Employment Incentives 2.5 Tax regime – Non regular resident 2.6 Social Security 2.7 Healthcare Access 3) RELOCATING TO PORTUGAL 3.1 LISBON 3.1.1 Accessibilities 3.1.1.1 Airport Connections 3.1.1.2 Road, Maritime and Public Transport Network 3.1.2 Human Resources 3.1.2.1 Education and Studies in Lisbon 3.2 PORTO 3.2.1 Accessibilities 3.2.2.1 Airport Connections PORTUGAL IN 1 3.2.2.2 Road and Public Transport Network 3.2.2 Human Resources 3.2.3.1 Education and Studies in Porto 3.3 Cost of Living comparison – Lisbon and Porto 3.3.1 Cost of living in Porto 4) BENCHMARKING 4.1 Doing Business 4.2 Innovation & technologies 4.3 Labour Competitive Costs 4.4 Real Estate Costs 4.5 General everyday life costs 5) CONCLUSION: WHY PORTUGAL? 5.1 Competitive advantages 6) OTHER INFORMATION 6.1 Useful websites 6.2 Sources PORTUGAL IN 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PORTUGAL COUNTRY ID Geographically, Portugal is located on the Iberian Peninsula being the westernmost Portugal has a population rounding country of mainland Europe. -

Portuguese Elections: Portugal Is Now a Country Caught Between Stability and Disaffection

blogs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2015/10/09/portuguese-elections-portugal-is-now-a-country-caught-between-stability-and-disaffection/ Portuguese elections: Portugal is now a country caught between stability and disaffection The governing centre-right coalition in Portugal won parliamentary elections on 4 October, but lost its majority in the Portuguese parliament. Luís de Sousa and Fernando Casal Bértoa assess what the results mean for the country’s party system. They write that Portugal has had an exceptionally stable party system in recent years and that this trend has continued, despite the financial crisis badly damaging the Portuguese economy. Nevertheless, there are high levels of disaffection among citizens, evident in the election’s record low turnout. On the morning of 5 October, the 115th birthday of the Portuguese Republic – one of the bank holidays that has been eliminated by the country’s government during the crisis period – Portuguese citizens woke-up to a rainy autumn day with a taste of sweet and sour in their mouths. Portugal re-elected the centre-right Portugal Ahead coalition formed by the ruling Social Democrats (PSD) and Christian Democrats (CDS/PP), the parties responsible for negotiating and implementing the country’s bailout. The question on everybody’s mind is why Portuguese voters did not choose to sanction at the ballot box the parties responsible for implementing austerity measures and for the hardship that has afflicted Portugal over the last four years. Moreover, why, in clear contrast to -

The 2015 Portuguese Legislative Election: Widening the Coalitional Space and Bringing the Extreme Left In

South European Society and Politics ISSN: 1360-8746 (Print) 1743-9612 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fses20 The 2015 Portuguese Legislative Election: Widening the Coalitional Space and Bringing the Extreme Left in Elisabetta De Giorgi & José Santana-Pereira To cite this article: Elisabetta De Giorgi & José Santana-Pereira (2016): The 2015 Portuguese Legislative Election: Widening the Coalitional Space and Bringing the Extreme Left in, South European Society and Politics To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2016.1181862 Published online: 12 May 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 85 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fses20 Download by: [b-on: Biblioteca do conhecimento online UL] Date: 18 May 2016, At: 03:57 SOUTH EUROPEAN SOCIETY AND POLITICS, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2016.1181862 The 2015 Portuguese Legislative Election: Widening the Coalitional Space and Bringing the Extreme Left in Elisabetta De Giorgi and José Santana-Pereira ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article provides an overview of the Portuguese legislative election Portugal; António Costa; BE; held on 4 October 2015 by exploring the economic and political PCP; PS context in which the election took place, the opinion polls, party positions and campaign issues, the results and, finally, the process that led to the formation of the first Socialist minority government supported by far-left parties. Due to this outcome, despite the relative majority of the votes obtained by the incumbent centre-right coalition, we argue that this election result cannot be interpreted as a victory of austerity, but rather as the first step towards contract parliamentarism in Portugal. -

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions.