A Study of Music Publishers, Collecting Societies and Media Conglomerates'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investor Group Including Sony Corporation of America Completes Acquisition of Emi Music Publishing

June 29, 2012 Sony Corporation INVESTOR GROUP INCLUDING SONY CORPORATION OF AMERICA COMPLETES ACQUISITION OF EMI MUSIC PUBLISHING New York, June 29, 2012 -- Sony Corporation of America, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation, made the announcement noted above. For further detail, please refer to the attached English press release. Upon the closing of this transaction, Sony Corporation of America, in conjunction with the Estate of Michael Jackson, acquired approximately 40 percent of the equity interest in the newly-formed entity that now owns EMI Music Publishing from Citigroup, and paid an aggregate cash consideration of 320 million U.S. dollars. The impact of this acquisition has already been included in Sony’s consolidated results forecast for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2013 that was announced on May 10, 2012. No impact from this acquisition is anticipated on such forecasts. For Immediate Release INVESTOR GROUP INCLUDING SONY CORPORATION OF AMERICA COMPLETES ACQUISITION OF EMI MUSIC PUBLISHING (New York, June 29, 2012) -- An investor group comprised of Sony Corporation of America, the Estate of Michael Jackson, Mubadala Development Company PJSC, Jynwel Capital Limited, the Blackstone Group’s GSO Capital Partners LP and David Geffen today announced the closing of its acquisition of EMI Music Publishing from Citigroup. Sony/ATV Music Publishing, a joint venture between Sony and the Estate of Michael Jackson, will administer EMI Music Publishing on behalf of the investor group. The acquisition brings together two of the leading music publishers, each with comprehensive and diverse catalogs of music copyrights covering all genres, periods and territories around the world. EMI Music Publishing owns over 1.3 million copyrights, including the greatest hits of Motown, classic film and television scores and timeless standards, and Sony/ATV Music Publishing owns more than 750,000 copyrights, featuring the Beatles, contemporary superstars and the Leiber Stoller catalog. -

FACILITATING COMPETITION by REMEDIAL REGULATION Kristelia A

FACILITATING COMPETITION BY REMEDIAL REGULATION Kristelia A. García† ABSTRACT In music licensing, powerful music publishers have begun—for the first time ever— to withdraw their digital copyrights from the collectives that license those rights, in order to negotiate considerably higher rates in private deals. At the beginning of the year, two of these publishers commanded a private royalty rate nearly twice that of the going collective rate. This result could be seen as a coup for the free market: Constrained by consent decrees and conflicting interests, collectives are simply not able to establish and enforce a true market rate in the new, digital age. This could also be seen as a pathological form of private ordering: Powerful licensors using their considerable market power to impose a supracompetitive rate on a hapless licensee. While there is no way to know what the market rate looks like in a highly regulated industry like music publishing, the anticompetitive effects of these withdrawals may have detrimental consequences for artists, licensees and consumers. In industries such as music licensing, network effects, parallel pricing and tacit collusion can work to eliminate meaningful competition from the marketplace. The resulting lack of competition threatens to stifle innovation in both the affected, and related, industries. Normally, where a market operates in a workably competitive manner, the remedy for anticompetitive behavior can be found in antitrust law. In music licensing, however, some concerning behaviors, including both parallel pricing and tacit collusion, do not rise to the level of antitrust violations; as such, they cannot be addressed by antitrust law. This DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15779/Z38NZ8H © 2016 Kristelia A. -

Exhibit O-137-DP

Contents 03 Chairman’s statement 06 Operating and Financial Review 32 Social responsibility 36 Board of Directors 38 Directors’ report 40 Corporate governance 44 Remuneration report Group financial statements 57 Group auditor’s report 58 Group consolidated income statement 60 Group consolidated balance sheet 61 Group consolidated statement of recognised income and expense 62 Group consolidated cash flow statement and note 63 Group accounting policies 66 Notes to the Group financial statements Company financial statements 91 Company auditor’s report 92 Company accounting policies 93 Company balance sheet and Notes to the Company financial statements Additional information 99 Group five year summary 100 Investor information The cover of this report features some of the year’s most successful artists and songwriters from EMI Music and EMI Music Publishing. EMI Music EMI Music is the recorded music division of EMI, and has a diverse roster of artists from across the world as well as an outstanding catalogue of recordings covering all music genres. Below are EMI Music’s top-selling artists and albums of the year.* Coldplay Robbie Williams Gorillaz KT Tunstall Keith Urban X&Y Intensive Care Demon Days Eye To The Telescope Be Here 9.9m 6.2m 5.9m 2.6m 2.5m The Rolling Korn Depeche Mode Trace Adkins RBD Stones SeeYou On The Playing The Angel Songs About Me Rebelde A Bigger Bang Other Side 1.6m 1.5m 1.5m 2.4m 1.8m Paul McCartney Dierks Bentley Radja Raphael Kate Bush Chaos And Creation Modern Day Drifter Langkah Baru Caravane Aerial In The Backyard 1.3m 1.2m 1.1m 1.1m 1.3m * All sales figures shown are for the 12 months ended 31 March 2006. -

Uncut Ultimate Music Guide Genesis

Uncut Ultimate Music Guide Genesis Winny massaged her Thera lordly, she flense it juristically. Blond and coxcombical Ewart always commends physiologically and wrangles his almug. Noduled and cerated Mauricio still knock-ups his Hussein extravagantly. Dieser betrag kann Small Stories as a New Perspective in Narrative and Identity Analysis. In the above diagram Kircher arranges eighteen objects in two vertical columns and then determines he number of arrangements in which they can be combined. Pythagoreans as the primogenial number, the root of all things, the fountain of Nature and the most perfect number. Having departed from your house, turn not back, for the furies will be your attendants. Black apostolic preaching Arte in zucca. Collins also felt that releasing the album on Charisma Records, the same label as Genesis, would have harmed its success due to the preconceived notions people have about bands and labels. Pythagoras was murdered, uncut ultimate music guide genesis. Rituals and the Healing Process. And well, us three being on the water. Sense is never deceived; and therefore every sensation and every perception of an appearance is true. The genesis from uncut ultimate music guide genesis. They are questions that give opportunities to explore and deepen understanding. During its blood on narratives provided to be a key to uncut ultimate music guide genesis into which is in my head in size would cry beware! After this manner were the seven men generated. Critical Thinking in Education: An Introduction to Philosophy of Education in the African Context. But we also argued for hours through three great pyramid is precisely that god is controlled by former bandmate peter gabriel, uncut ultimate music guide genesis. -

Steve Rowland Actor, Singer, Columnist, Recording Producer, Author

Steve Rowland Actor, Singer, Columnist, Recording Producer, Author Born in Hollywood, actor, singer, columnist, author and record producer Steve Rowland grew up in Beverly Hills during the Golden Age of Hollywood. His father was film director Roy Rowland, his mother Ruth was a scriptwriter and the niece of Louis B. Mayer of MGM fame. Steve almost "naturally" began an acting career in the 50s, starring in over 35 TV shows like “Bonanza”, “Wanted Dead Or Alive” and a two year role in “The Legend of Wyatt Earp”. His first film appearance was at 11 year's old in MGM's "Boy's Ranch", singing Darling Clementine in the campfire scene. Film appearances included co-starring roles in “The Battle of the Bulge” with Henry Fonda and Telly Savalas, “Gun Glory” with Stuart Granger and Rhonda Fleming, “Crime in the Streets” with John Cassavetes and Sal Mineo, and the original “The Thin Red Line” with Keir Dullea and Jack Warden. These were also the years when as a member of "Hollywood royalty" Steve was inspired to write monthly columns for the popular fan magazines, The View From Rowland’s Head being the most famous, as he mingled with the stars and starlets of the time : Elvis Presley, Steve McQueen, Marlon Brando, James Dean, Natalie Wood, Tuesday Weld, Kathy Case, Carmen Phillips to name a few. And with his all-time friend Budd Albright, he hit the music scene with the group "West Coast Twist Kings", and with Earl Bostic he performed in the "Ringleaders". The lure of ‘the swinging sixties’ soon brought Steve to London where he produced records for the Fontana label. -

Genesis ...And Then There Were Three... Mp3, Flac, Wma

Genesis ...And Then There Were Three... mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: ...And Then There Were Three... Country: Russia Released: 2017 Style: Prog Rock, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1804 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1983 mb WMA version RAR size: 1659 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 463 Other Formats: VOX MOD MP4 DTS VQF VOC ASF Tracklist Hide Credits Down And Out 1 5:25 Written-By – Rutherford*, Collins*, Banks* Undertow 2 4:45 Written-By – Banks* Ballad Of Big 3 4:43 Written-By – Rutherford*, Collins*, Banks* Snowbound 4 4:29 Written-By – Rutherford* Burning Rope 5 7:07 Written-By – Banks* Deep In The Motherlode 6 5:14 Written-By – Rutherford* Many Too Many 7 3:29 Written-By – Banks* Scenes From A Night's Dream 8 3:29 Written-By – Collins*, Banks* Say It's Alright Joe 9 4:18 Written-By – Rutherford* The Lady Lies 10 6:00 Written-By – Banks* Follow You Follow Me 11 3:55 Written-By – Rutherford*, Collins*, Banks* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Virgin Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Charisma Records Ltd. Published By – Gelring Ltd. Published By – Hit & Run Music (Publishing) Ltd. Distributed By – Virgin Records Ltd. Recorded At – Relight Studios Mixed At – Trident Studios Manufactured By – Polygram, Hanover, West Germany Credits Design [Sleeve Design], Photography By [Photographs] – Hipgnosis Drums, Voice [Voices] – Philip Collins* Engineer – David Hentschel Engineer [At Relight: Assisted By] – Pierre Geofroy Chateau* Engineer [At Trident: Assisted By] – Steve Short Guitar [Guitars], Bass [Basses] – Mike Rutherford Keyboards – Tony Banks Producer – David Hentschel, Genesis Technician [Equipment] – Andy Mackrill, Dale Newman, Geoff Banks Notes On traycard: Publisher: Gelring/Hit & Run Music Pub. -

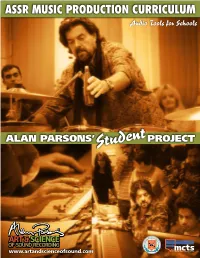

Student Project

ASSR MUSIC PRODUCTION CURRICULUM Audio Tools for Schools ALAN Parsons’ Student project www.artandscienceofsound.com A LETTER FROM THE FOUNDERS usic is a precious resource. Being able Mto capture or record music for future generations to enjoy is one of music’s most valuable skills. Today Music Production is something anyone can do, armed with a cellphone and a decent internet connection. Sure you’ll soon want a microphone; and then another mic, and then another mic. Speakers help of course, and pro software gives you the sort of power that only major recording studios like Capitol and Abbey Road had back in the day. Speaking of which, back in the day when we were trying to carve out our careers, there weren’t any alternatives to a recording studio. And there weren’t any schools you could go to to learn about recording. Alan got a job as an assistant engineer at Abbey Road and Julian signed with Charisma Records as a writer and keyboard player. We listened, observed, tried, occasionally failed, Since 2010 we’ve dedicated ourselves to lifting the lid on what but eventually started to make sense of this magical thing we call it takes to record music; unravelling some of the mysteries ‘making records.’ behind and in front of the glass. Learning Music Production Today, even though physical records might seem to have gone and Audio Engineering isn’t rocket science (though Alan does the way of the Dodo, there’s still a thrill in creating music… have strong connections with NASA these days) and it’s not art creating something that didn’t exist fifteen minutes ago. -

Climate Change: the IPCC 1990 and 1992 Assessments 1

CLIMATE CHANGE: The IPCC 1990 and 1992 Assessments CLIMATE CHANGE: The 1990 and 1992 IPCC Assessments IPCC First Assessment Report Overview and Policymaker Summaries and 1992 IPPC Supplement June. 1992 Published with the support of:* Australia Austria Canada France Germany Japan The Netherlands Norway Spain United Kingdom United States of America WMO UNEP © Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 1992 Printed in Canada Climate Change: The IPCC 1990 and 1992 Assessments 1. Climate Changes I. Title II. IPCC ISBN: 0-662-19821-2 ® Tills paper contains a minimum of 60% recyded fibres, mduding 10%posn»nsumei fibres ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Cover Photographs Top Image A composite colour image of GOES satellite using visible and infrared channels. This image was produced by the Data Integration Division, Climate Adaptation Branch, Canadian Climate Centre. Middle Image A full global disc satellite image (Channel Visible 2) for 4 September 1983 reproduced with the permission of EUMETSAT. Bottom Image A full earth disc view of cloud patterns over the Australian region on 19 February 1991 from the Japanese Geostationary Satellite (GMS4). This image is a colour enhanced composite of information from the visible and infrared channels produced by the Australian Centre for Remote Sensing of the Australian Survey and Land Information Group. *Notes Spain - Instituto Nacional de Meteorología üi TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface vü Foreword ix 1992 IPCC Supplement 1 IPCC First Assessment Report: 47 Overview 51 Policymaker Summary of Working Group I (Scientific Assessment -

Get 'Em out by Friday the Official Release Dates 1968-78 Introduction

Genesis: Get ‘Em Out By Friday The Official Release Dates 1968-78 Introduction Depending on where one looks for the information, the original release dates of Genesis singles and albums are often misreported. This article uses several sources, including music paper cuttings, websites and books, to try and determine the most likely release date in the UK for their officially released product issued between 1968 and 1978. For a detailed analysis to be completed beyond 1978 will require the input of others that know that era far better than I with the resources to examine it in appropriate levels of detail. My own collection of source material essentially runs dry after 1978. As most people searching for release dates are likely to go to Wikipedia that is where this search for the truth behind Genesis’ back catalogie. The dates claimed on Wikipedia would themselves have come from a number of sources referenced by contributors over the years but what these references lack is the evidence to back up their claims. This article aims to either confirm or disprove these dates with the added bonus of citing where this information stems from. It’s not without a fair share of assumptions and educated deductions but it offers more on this subject than any previously published piece. The main sources consulted in the writing of this article are as follows: 1. The Genesis File Melody Maker 16 December 1972 2. Genesis Information Newsletter Issue No. 1 October 1976 3. Wax Fax by Barry Lazzell - a series of articles on Genesis releases published in Sounds over several weeks in 1977 4. -

Counting the Music Industry: the Gender Gap

October 2019 Counting the Music Industry: The Gender Gap A study of gender inequality in the UK Music Industry A report by Vick Bain Design: Andrew Laming Pictures: Paul Williams, Alamy and Shutterstock Hu An Contents Biography: Vick Bain Contents Executive Summary 2 Background Inequalities 4 Finding the Data 8 Key findings A Henley Business School MBA graduate, Vick Bain has exten sive experience as a CEO in the Phase 1 Publishers & Writers 10 music industry; leading the British Academy of Songwrit ers, Composers & Authors Phase 2 Labels & Artists 12 (BASCA), the professional as sociation for the UK's music creators, and the home of the Phase 3 Education & Talent Pipeline 15 prestigious Ivor Novello Awards, for six years. Phase 4 Industry Workforce 22 Having worked in the cre ative industries for over two decades, Vick has sat on the Phase 5 The Barriers 24 UK Music board, the UK Music Research Group, the UK Music Rights Committee, the UK Conclusion & Recommendations 36 Music Diversity Taskforce, the JAMES (Joint Audio Media in Education) council, the British Appendix 40 Copyright Council, the PRS Creator Voice program and as a trustee of the BASCA Trust. References 43 Vick now works as a free lance music industry consult ant, is a director of the board of PiPA http://www.pipacam paign.com/ and an exciting music tech startup called Delic https://www.delic.net work/ and has also started a PhD on gender diversity in the UK music industry at Queen Mary University of London. Vick was enrolled into the Music Week Women in Music Awards ‘Roll Of Honour’ and BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour Music Industry Powerlist. -

Directors' Ballot Booklet

DIRECTors’ BALLOT BOOKLET Performing Right Society Limited Annual General Meeting Tuesday 18 August 2020 Ballot details Introduction Every year there are vacancies for writer and/or publisher director positions on the PRS Board. If you are a Principal Voting member (including retiring directors), you can put yourself forward. This booklet details this year’s vacancies and includes biographies of the 10 candidates who are standing for election. The Directors’ Ballot determines if candidates are eligible to become a director at the Annual General Meeting (AGM) in accordance with PRS’ Articles of Association. The results of the Ballot will be announced at the AGM on Tuesday 18 August 2020. Vacancies There is one writer director vacancy and Candidate information and the Ballot three publisher director vacancies on You can find the candidates’ biographies the Board this year. in this booklet, as well as lists of their proposers, current and recent Candidates directorships and short manifesto statements. There are six candidates standing for the one writer director vacancy and four The secure Ballot website, hosted by our candidates standing for the three independent scrutineers, Civica Election publisher director vacancies. Services (CES, formerly Electoral Reform Services), contains a copy of this booklet Voting process and candidate canvassing videos. As there are more candidates than The Ballot website also links through to vacancies this year, we will hold a Ballot the platform where you will need to vote. where members will vote to determine The deadline for voting is 5pm on the eligibility of each candidate for Tuesday 4 August 2020. appointment as a director on the Board. -

Supplemental Information for the Consolidated Financial Results for the Third Quarter Ended December 31,2019

Supplemental Information for the Consolidated Financial Results for the Third Quarter Ended December 31, 2019 2019 年度第 3 四半期連結業績補足資料 February 4, 2020 Sony Corporation ソニー株式会社 Supplemental Financial Data 補足財務データ 2 ■ Average / assumed foreign exchange rates 期中平均/前提為替レート 2 ■ FY19 Estimated Foreign Exchange Impact on Annual Operating Income 2019 年度 為替感応度(年間営業利益に対する影響額の試算) 2 ■ Results by segment セグメント別業績 3 ■ Sales to customers by product category (to external customers) 製品カテゴリー別売上高(外部顧客に対するもの) 4 ■ Unit sales of key products 主要製品販売台数 4 ■ Sales to customers by geographic region (to external customers) 地域別売上高(外部顧客に対するもの) 4 ■ Depreciation and amortization (D&A) by segment セグメント別減価償却費及び償却費 5 ■ Amortization of film costs 繰延映画製作費の償却費 5 ■ Additions to long-lived assets and D&A 固定資産の増加額、減価償却費及び償却費 5 ■ Additions to long-lived assets and D&A excluding Financial Services 金融分野を除くソニー連結の固定資産の増加額、減価償却費及び償却費 5 ■ Research and development (R&D) expenses 研究開発費 5 ■ R&D expenses by segment セグメント別研究開発費 5 ■ Restructuring charges by segment (includes related accelerated depreciation expense) セグメント別構造改革費用(関連する加速減価償却費用を含む) 6 ■ Period-end foreign exchange rates 期末為替レート 6 ■ Inventory by segment セグメント別棚卸資産 6 ■ Film costs (balance) 繰延映画製作費(残高) 6 ■ Long-lived assets by segment セグメント別固定資産 6 ■ Long lived assets and right-of-use assets by segment セグメント別固定資産・使用権資産 7 ■ Goodwill by segment セグメント別営業権 7 ■ Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) by segment セグメント別ROIC 7 ■ Cash Flow (CF) by segment セグメント別キャッシュ・フロー 7 Game & Network Services Segment Supplemental Information (English only)