Counting the Music Industry: the Gender Gap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cord Weekly

THE CORD WEEKLY Volume 29, Number 25 Thursday Mar. 23,1989 Wilfrid Laurier University Abandon all hope ye who enter here Cord Photo: Liza Sardi The Cord Weekly 2 Thursday, March 23,1989 THE CORD WEEKLY |1 keliv/f!rent-a-car ; SAVE $5.00 ! March 23,1989 Volume 29, Number 25 ■ ON ANY CAR RENTAL ■ I Editor-in-Chief Cori Ferguson ■ NEWS Editor Bryan C. Leblanc Associate Jonathan Stover Contributors Tim Sullivan Frances McAneney COMMENT ■ ■ Contributors 205 WEBER ST. N. Steve Giustizia l 886-9190 l FEATURES Free Customer Pick-up Delivery ■ Editor vacant and Contributors Elizabeth Chen ENTERTAINMENT Editor Neville J. Blair Contributors Dave Lackie Cori Cusak Jonathan Stover Kathy O'Grady Brad Driver Todd Bird SPORTS Editor Brad Lyon Contributors Brian Owen Sam Syfie Serge Grenier Lucien Boivin Raoul Treadway Wayne Riley Oscar Madison Fidel Treadway Kenneth J. Whytock Janet Smith DESIGN AND ASSEMBLY Production Manager Kat Rios Assistants Sandy Buchanan Sarah Welstead Bill Casey Systems Technician Paul Dawson Copy Editors Shannon Mcllwain Keri Downs Contributors \ Jana Watson Tony Burke CAREERS Andre Widmer 112 PHOTOGRAPHY Manager Vicki Williams Technician Jon Rohr gfCHALLENGE Graphic Arts Paul Tallon Contributors Liza Sardi Brian Craig gfSECURITY Chris Starkey Tony Burke J. Jonah Jameson Marc Leblanc — ADVERTISING INFLEXIBILITY Manager Bill Rockwood Classifieds Mark Hand gfPRESTIGE Production Manager Scott Vandenberg National Advertising Campus Plus gf (416)481-7283 SATISFACTION CIRCULATION AND FILING Manager John Doherty Ifyou want theserewards Eight month, 24-issue CORD subscription rates are: $20.00 for addresses within Canada inacareer... and $25.00 outside the country. Co-op students may subscribe at the rate of $9.00 per four month work term. -

The Creative Conver

TWO PETERRAINMAKERS EDGETHE CREATIVE CONVERSATION s chief of RCA, Peter Edge has presided over one of the splashiest rosters in the biz, which has culminated in big chart successes, top-tier Grammy love and, occa- sionally, pop-cultural godhead for his acts. Edge’s keen A&R chops Aand artist whispering have been integral to his reign, and he has been acutely sensitive to the shifting winds of the marketplace. “I’m always looking for a unique propo- sition,” Edge said a decade and a half ago, and it clearly resonates today. “I’m really attracted to people who have an abundance of talent because I’m just in awe of that, being a music fan.” “Peter Edge loves music so much, it’s his heart and soul,” notes one of Edge’s Grammy-winning, chart-topping signings, Switch, where he booked artists such as Sade Khalid. “I’ve had such meaningful artistic and Grace Jones. His work there caught conversations with him, and I’m always in the eye of Simon Fuller, who hired him as awe of his knowledge and his passion.” an A&R rep at Chrysalis Music Publishing; “I have known and worked with Peter he subsequently moved to the label side at since I first started in this business,” says Chrysalis and was tasked with launching the manager Brandon Creed, “and he has London-based Cooltempo imprint in 1985, always been a very kind and soulful leader in tandem with producer Danny D. and personal mentor to me. His taste and In the U.K., the label would release talent are inspiring, and he’s as authen- music by Erik B and Rakim, EPMD, tic and genuine as an executive as he is a The Real Roxanne, Slick Rick and Doug human being.” E. -

Ebook Download This Is Grime Ebook, Epub

THIS IS GRIME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hattie Collins | 320 pages | 04 Apr 2017 | HODDER & STOUGHTON | 9781473639270 | English | London, United Kingdom This Is Grime PDF Book The grime scene has been rapidly expanding over the last couple of years having emerged in the early s in London, with current grime artists racking up millions of views for their quick-witted and contentious tracks online and filling out shows across the country. Sign up to our weekly e- newsletter Email address Sign up. The "Daily" is a reference to the fact that the outlet originally intended to release grime related content every single day. Norway adjusts Covid vaccine advice for doctors after admitting they 'cannot rule out' side effects from the Most Popular. The awkward case of 'his or her'. Definition of grime. This site uses cookies. It's all fun and games until someone beats your h Views Read Edit View history. During the hearing, David Purnell, defending, described Mondo as a talented musician and sportsman who had been capped 10 times representing his country in six-a-side football. Fernie, aka Golden Mirror Fortunes, is a gay Latinx Catholic brujx witch — a combo that is sure to resonate…. Scalise calls for House to hail Capitol Police officers. Drill music, with its slower trap beats, is having a moment. Accessed 16 Jan. This Is Grime. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. More On: penn station. Police are scrambling to recover , pieces of information which were WIPED from records in blunder An unwillingness to be chained to mass-produced labels and an unwavering honesty mean that grime is starting a new movement of backlash to the oppressive systems of contemporary society through home-made beats and backing tracks and enraged lyrics. -

The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive A Change is Gonna Come: The Future of Copyright and the Artist/Record Label Relationship in the Music Industry A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies And Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of Masters of Laws in the College of Law University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Kurt Dahl © Copyright Kurt Dahl, September 2009. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Dean of the College of Law University of Saskatchewan 15 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A6 i ABSTRACT The purpose of my research is to examine the music industry from both the perspective of a musician and a lawyer, and draw real conclusions regarding where the music industry is heading in the 21st century. -

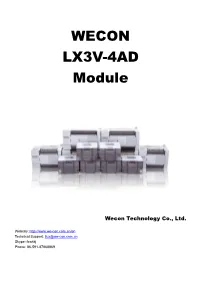

WECON LX3V-4AD Module

WECON LX3V-4AD Module Wecon Technology Co., Ltd. Website: http://www.we-con.com.cn/en Technical Support: [email protected] Skype: fcwkkj Phone: 86-591-87868869 LX3V-4AD Extension Module 1. Introduction The LX3V-4AD special module has four input channels.The input channels receive analog signals and convert them into a digital value.This is called an A/D conversion, the maximum resolution is 12 bits. The selection of voltage or current based input/output is by user wiring.Analog ranges of -10 to 10V DC (resolution:5mV), and/or 4 to 20mA, -20 to 20mA(resolution:20µA) may be selected. Data transfer between the LX3V-4AD and the LX3V main unit is by buffer memory exchange. There are 32 buffer memories (each of 16 bits) in the LX3V-4AD. LX3V-4AD consume 5V voltage from LX3V main unit or active extension unit,90mA current of power supply. 2. Dimensions ① Extension cable and connector ② Com LED:Light when communicating ③ Power LED:Light when connect to 24V ④ State LED:Light when normal condition ⑤ Module name ⑥ Analog signal output terminal ⑦ Extension module interface ⑧ DIN rail mounting slot ⑨ DIN rail hook ⑩ Mounting holes(φ4.5) - 2 - 3. Terminal layouts ① The analog input is received through a twisted pair shielded cable. This cable should be wired separately from power lines or any other lines which may induce electrical noise. ② If a voltage ripple occurs during input, or there is electrically induced noise on the external wiring, connect a smoothing capacitor of 0.1 to 0.47µF, 25V. ③ If you are using current input, connect the V+ and I+ terminals to each other. -

Tx2n-4Ad-Tc Special Function Block User's Guide

HCFA CORPORATION LIMITED TX2N-4AD-TC SPECIAL FUNCTION BLOCK USER’S GUIDE This manual contains text, diagrams and explanations which will guide the reader in the correct installation and operation of the TX2N-4AD-TC special function block and should be read and understood before attempting to install or use the unit. Guidelines for the Safety of the User and Protection of the TX2N-4AD-TC special function block. This manual should be used by trained and competent personnel. The definition of such a person or persons is as follows: a) Any engineer using the product associated with this manual, should be of a competent nature, trained and qualified to the local and national standards. These engineers should be fully aware of all aspects of safety with regards to automated equipment. b) Any commissioning or service engineer must be of a competent nature, trained and qualified to the local and national standards. c) All operators of the completed equipment should be trained to use this product in a safe and coordinated manner in compliance to established safety practices. Note: The term ‘completed equipment’ refers to a third party constructed device which contains or uses the product associated with this manual. Notes on the Symbols Used in this Manual At various times throughout this manual certain symbols will be used to highlight points of information which are intended to ensure the users’ personal safety and protect the integrity of equipment. 1) Indicates that the identified danger WILL cause physical and property damage. 2) Indicates that the identified danger could POSSIBLYcause physical and property damage. -

Investor Group Including Sony Corporation of America Completes Acquisition of Emi Music Publishing

June 29, 2012 Sony Corporation INVESTOR GROUP INCLUDING SONY CORPORATION OF AMERICA COMPLETES ACQUISITION OF EMI MUSIC PUBLISHING New York, June 29, 2012 -- Sony Corporation of America, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation, made the announcement noted above. For further detail, please refer to the attached English press release. Upon the closing of this transaction, Sony Corporation of America, in conjunction with the Estate of Michael Jackson, acquired approximately 40 percent of the equity interest in the newly-formed entity that now owns EMI Music Publishing from Citigroup, and paid an aggregate cash consideration of 320 million U.S. dollars. The impact of this acquisition has already been included in Sony’s consolidated results forecast for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2013 that was announced on May 10, 2012. No impact from this acquisition is anticipated on such forecasts. For Immediate Release INVESTOR GROUP INCLUDING SONY CORPORATION OF AMERICA COMPLETES ACQUISITION OF EMI MUSIC PUBLISHING (New York, June 29, 2012) -- An investor group comprised of Sony Corporation of America, the Estate of Michael Jackson, Mubadala Development Company PJSC, Jynwel Capital Limited, the Blackstone Group’s GSO Capital Partners LP and David Geffen today announced the closing of its acquisition of EMI Music Publishing from Citigroup. Sony/ATV Music Publishing, a joint venture between Sony and the Estate of Michael Jackson, will administer EMI Music Publishing on behalf of the investor group. The acquisition brings together two of the leading music publishers, each with comprehensive and diverse catalogs of music copyrights covering all genres, periods and territories around the world. EMI Music Publishing owns over 1.3 million copyrights, including the greatest hits of Motown, classic film and television scores and timeless standards, and Sony/ATV Music Publishing owns more than 750,000 copyrights, featuring the Beatles, contemporary superstars and the Leiber Stoller catalog. -

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising

19.05.21 Notable Industry Recognition Awards List • ADC Advertising Awards • AFI Awards • AICE & AICP (US) • Akil Koci Prize • American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal in Music • American Cinema Editors • Angers Premier Plans • Annie Awards • APAs Awards • Argentine Academy of Cinematography Arts and Sciences Awards • ARIA Music Awards (Australian Recording Industry Association) Ariel • Art Directors Guild Awards • Arthur C. Clarke Award • Artios Awards • ASCAP awards (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) • Asia Pacific Screen Awards • ASTRA Awards • Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTS) • Australian Production Design Guild • Awit Awards (Philippine Association of the Record Industry) • BAA British Arrow Awards (British Advertising Awards) • Berlin International Film Festival • BET Awards (Black Entertainment Television, United States) • BFI London Film Festival • Bodil Awards • Brit Awards • British Composer Awards – For excellence in classical and jazz music • Brooklyn International Film Festival • Busan International Film Festival • Cairo International Film Festival • Canadian Screen Awards • Cannes International Film Festival / Festival de Cannes • Cannes Lions Awards • Chicago International Film Festival • Ciclope Awards • Cinedays – Skopje International Film Festival (European First and Second Films) • Cinema Audio Society Awards Cinema Jove International Film Festival • CinemaCon’s International • Classic Rock Roll of Honour Awards – An annual awards program bestowed by Classic Rock Clio -

FACILITATING COMPETITION by REMEDIAL REGULATION Kristelia A

FACILITATING COMPETITION BY REMEDIAL REGULATION Kristelia A. García† ABSTRACT In music licensing, powerful music publishers have begun—for the first time ever— to withdraw their digital copyrights from the collectives that license those rights, in order to negotiate considerably higher rates in private deals. At the beginning of the year, two of these publishers commanded a private royalty rate nearly twice that of the going collective rate. This result could be seen as a coup for the free market: Constrained by consent decrees and conflicting interests, collectives are simply not able to establish and enforce a true market rate in the new, digital age. This could also be seen as a pathological form of private ordering: Powerful licensors using their considerable market power to impose a supracompetitive rate on a hapless licensee. While there is no way to know what the market rate looks like in a highly regulated industry like music publishing, the anticompetitive effects of these withdrawals may have detrimental consequences for artists, licensees and consumers. In industries such as music licensing, network effects, parallel pricing and tacit collusion can work to eliminate meaningful competition from the marketplace. The resulting lack of competition threatens to stifle innovation in both the affected, and related, industries. Normally, where a market operates in a workably competitive manner, the remedy for anticompetitive behavior can be found in antitrust law. In music licensing, however, some concerning behaviors, including both parallel pricing and tacit collusion, do not rise to the level of antitrust violations; as such, they cannot be addressed by antitrust law. This DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15779/Z38NZ8H © 2016 Kristelia A. -

Full Music Credits

Music Supervisor Chris Gough Mana Music Mushroom Licensing Ann-Marie Meadows Music Mixer Robin Grey Alan Eaton Studios Original Music Recorded at Hot House - Craig Harnath Original Music Mix Ross Cockle FX & Music Editor Craig Carter Original Music Composed by Martin Lubran David Bowers "Jackson" (Wheeler/Rodgers) EMI Music Publishing Australia, Performed by Catherine Wearne and Andrew Travis, Produced by Jim Bowman, Recorded at Electric Avenue "Don't It Get You Down" (Kennedy/Palmer/Jones) Mushroom Music, Performed by Dead Star, Courtesy of Mushroom Records "Goldfinger" (Wheeler) PolyGram Publishing, Performed by Ash, Courtesy of Infectious/Mushroom Records "Fun For Me" (Brydon/Murphy) Chrysalis Music/Mushroom Music, Performed by Moloko Courtesy of Echo/Liberation "Puppy Love" (Anka) Chrysalis Music/Mushroom Music Performed by Banana Oil, Courtesy of Mushroom Records "Cruise Control" (Matthews/Lawry/Nevison/Fell/Sweeny/ McDonald) Flying Nun Music/Mushroom Music Performed by Headless Chickens Courtesy of Flying Music/Mushroom Records "Help Yourself" (Donida/Mogol/Fishman) Mushroom Music Performed by Tom Jones, Courtesy of PolyGram "No Reason" (Salmon/Perkins) PolyGram Publishing, Performed by Beasts of Bourbon, Courtesy of Red Eye/Polydor Records "Lemonsuck" (Handley) Mushroom Music, Performed by Pollyanna, Courtesy of Bark/Mushroom Records "So Long Marianne" (Cohen) Chrysalis Music/Mushroom Music Performed by The Stone Cold Boners & Hugo Weaving "Rock and Roll" (Reed) Oakfield Avenue/EMI Music Ltd Performed by The Stone Cold Boners & Hugo -

03/31/2018 Daily Program Listing II 02/05/2018 Page 1 of 124 Start Title Thu, Mar 01, 2018 Subtitle Ster

Daily Program Listing II 43.1 Date: 02/05/2018 03/01/2018 - 03/31/2018 Page 1 of 124 Thu, Mar 01, 2018 Title Start Subtitle Distrib Stereo Cap AS2 Episode 00:00:01 Great Decisions In Foreign Policy NETA (S) (CC) N/A #903H China: The New Silk Road China is the second largest economy in the world, and it's expected to bump the U.S. out of the top rank in less than a decade. Beijing is increasingly looking beyond China's borders, toward investment in Asia and across the world. What does China's massive One Belt One Road initiative mean for America? 00:30:00 In Good Shape - The Health Show WNVC (S) (CC) N/A #508H 01:00:00 The Lowertown Line. APTEX (S) (CC) N/A #124H Bruise Violet 01:30:00 Songs at the Center APTEX (S) (CC) N/A #110H Artists: Tim Easton, Talisha Holmes, Nathan Bell, Mark Brinkman, and hosted by songwriter Eric Gnezda. Tim Easton was nominated twice in the 9th Annual Independent Music Awards, including for Best Americana Song. Originally from Akron, he is now based in Nashville. He tours worldwide. He recently re-released his first album, Special 20, on vinyl. He sings "Elmore James." Talisha Holmes is known for her intimacy and energy as a performer. She has opened for Dwele, John Legend, Styx, Stephanie Mills, Ohio Players and others. With an eclectic style fusing jazz, blues, folk, rock and choral music, Talisha performs regularly with the Columbus Jazz Orchestra. She sings "Follow Me." Nathan Bell composed the music for The Day After Stonewall Died, a movie that was awarded first prize at the 2014 Cannes Short Film Festival. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon.