App 3 Thesis Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FIS Congress Preview Costa Navarino FINAL

INTERNATIONAL SKI FEDERATION Blochstrasse 2 3653 Oberhofen/Thunersee Switzerland FOR MORE INFORMATION Jenny Wiedeke FIS Communications Manager Mobile: + 41 79 449 53 99 E-Mail: [email protected] Oberhofen, Switzerland 23.04.2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FIS MEDIA INFO FIS Congress 2018 to take place in Costa Navarino (GRE) Approximately 1,000 delegates representing more than 80 Member National Ski Associations of the International Ski Federation (FIS) are scheduled to participate in the 51st International Ski Congress in Costa Navarino (GRE) from 13 th to 19 th May 2018. As part of the Congress Week, the FIS Council as well as the various FIS Technical Committees, Sub-Committees and Working Groups will meet from Sunday 13 th to Wednesday 16 th May, whilst the FIS Congress (General Assembly) itself takes place on Friday 18 th May. The Organisers of the FIS Ski Flying World Championships 2022 and the FIS Alpine, Nordic, Freestyle Ski and Snowboard World Championships 2023 will be elected by the FIS Council on Thursday 17 th May. The six Candidates (see p. 2) will present their concepts to all Congress participants from display stands and during the respective Technical Committee meetings as well as having a final opportunity to present to the FIS Council on Tuesday 15 th May. The announcement of the four elected Organisers will take place on Thursday at approximately 19:00 local time (20:00 CET). A live stream from the announcement will be available on the FIS Facebook channels. Representing the highest decision-making authority within FIS, the Congress will take place on Friday, 18 th May. -

National Sports Federations (Top Ten Most Funded Olympic Sports)

National Sports Federations (top ten most funded Olympic sports) Coverage for data collection 2020 Country Name of federation EU Member States Belgium (French Community) Associations clubs francophones de Football Association Francophone de Tennis Ligue Belge Francophone d'Athlétisme Association Wallonie-Bruxelles de Basket-Ball Ligue Francophone de Hockey Fédération francophone de Gymnastique et de Fitness Ligue Francophone de Judo et Disciplines Associées Ligue Francophone de Rugby Aile francophone de la Fédération Royale Belge de Tennis de Table Ligue équestre Wallonie-Bruxelles Belgium (Flemish Community) Voetbal Vlaanderen Gymnastiekfederatie Vlaanderen Volley Vlaanderen Tennis Vlaanderen Wind en Watersport Vlaanderen Vlaamse Atletiekliga Vlaamse Hockey Liga Vlaamse Zwemfederatie Cycling Vlaanderen Basketbal Vlaanderen Belgium (German Community) Verband deutschsprachiger Turnvereine Interessenverband der Fußballvereine in der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft Ostbelgischer Reiterverband Ostbelgischer Tischtennisverband Regionaler Sportverband der Flachbahnschützen Ostbelgiens Regionaler Tennisverband der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft Verband Ostbelgischer Radsportler Taekwondo verband der Deutschsprachigen Gemeinschaft Ostbelgischer Ski- und Wintersportverband Regionaler Volleyballverband VoG Bulgaria Bulgarian Boxing Federation Bulgarian Ski Federation Bulgarian Gymnastics Federation Bulgarian Wrestling Federation Bulgarian Volleyball Federation Bulgarian Weightlifting Federation Bulgarian Judo Federation Bulgarian Canoe-Kayak Federation -

Finnish Ski Association Pohjola Sports Cover 1 June 2020 – 31 May 2021 Ski Pass, Policy Code 06-8698959

Finnish Ski Association Pohjola Sports Cover 1 June 2020 – 31 May 2021 Ski Pass, policy code 06-8698959 For whom? Ski Pass, EUR Adults Born 2002 or earlier 37 Youth Born 2003 or later 27 A Ski Pass is an inexpensive licence product for non-competitive skiing of various types (alpine, freestyle, cross-country, ski jumping, Nordic combined). The licence fee always includes Sports Cover for ordinary skiers to cover snow sports. In addition to non-competitive sports, a Ski Pass entitles you to participate in competitions in all age groups as follows: Cross-country skiing and ski jumping/Nordic combined • regional and district competition • national competition organised by your own club or • the Hopeasompa finals • veterans’ Finnish championships in cross-country skiing Alpine and freestyle skiing • in club and regional competitions organised by SHL or SSF (the Finnish- and Swedish-language Ski Associations of Finland) that are outside the national competitive calendar, or • national competition organised by your own club Children aged 12 (born 2009) or younger and adults aged 65 (born 1956) or older may take part in national or higher competitions in all disciplines with a Ski Pass. Persons aged 13-64 (born 1957-2008) must have a competitive licence to participate in national or higher competitions. How to buy a Ski Pass You can buy a Ski Pass at www.suomisport.fi. Read the instructions on the Finnish Ski Association's website www.hiihtoliitto.fi. The licence is valid once it has been paid. Sports Cover in brief Sports Cover provides compensation for injuries resulting from a sudden event, such as rupture of the Achilles tendon or a dislocated knee. -

International Ski Federation (FIS)

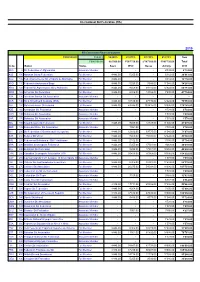

International Ski Federation (FIS) 2019 FIS Calculation Financial Support 5'000'000.00 100.00% 12.500% 21.875% 43.750% 21.875% New 5'000'000.00 625'000.00 1'093'750.00 2'187'500.00 1'093'750.00 Total Code Nation Status Basic WSC Races Activity 2019 AFG 0 Ski Federation of Afghanistan Associate Member - - - 4'734.00 4'734.00 ALB 100 Albanian Skiing Federation Full Member 8'446.00 5'255.00 - 6'312.00 20'013.00 ALG 105 Féd. Algérienne de Ski et Sports de Montagne Full Member 8'446.00 - - 6'312.00 14'758.00 AND 110 Federació Andorrana d'Esquí Full Member 8'446.00 5'255.00 9'546.00 11'046.00 34'293.00 ARG 120 Federación Argentina de Ski y Andinismo Full Member 8'446.00 9'459.00 38'184.00 12'624.00 68'713.00 ARM 125 Armenian Ski Federation Full Member 8'446.00 6'306.00 19'092.00 7'890.00 41'734.00 ASA 130 American Samoa Ski Association Associate Member - - - - - AUS 140 Ski & Snowboard Australia (SSA) Full Member 8'446.00 10'510.00 47'730.00 12'624.00 79'310.00 AUT 150 Österreichischer Skiverband Full Member 8'446.00 48'346.00 103'415.00 18'936.00 179'143.00 AZE 160 Azerbaijan Ski Federation Associate Member - - - 4'734.00 4'734.00 BAH 190 Bahamas Ski Association Associate Member - - - 1'578.00 1'578.00 BAR 170 Barbados Ski Association Associate Member - - - 1'578.00 1'578.00 BEL 180 Royal Belgian Ski Federation Full Member 8'446.00 9'459.00 12'728.00 11'046.00 41'679.00 BER 185 Bermuda Winter Ski Association Associate Member - 1'051.00 - 4'734.00 5'785.00 BIH 200 Ski Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina Full Member 8'446.00 12'612.00 39'775.00 11'046.00 71'879.00 BLR 210 Belarus Ski Union Full Member 8'446.00 8'408.00 15'910.00 12'624.00 45'388.00 BOL 220 Federacion Boliviana de Ski Y Andinismo Full Member 8'446.00 2'102.00 - 3'156.00 13'704.00 BRA 230 Brazilian Snow Sports Federation Full Member 8'446.00 5'255.00 17'501.00 9'468.00 40'670.00 BUL 240 Bulgarian Ski Federation Full Member 8'446.00 9'459.00 17'501.00 14'202.00 49'608.00 CAN 250 Canadian Snowsports Association CSA Full Member 8'446.00 30'479.00 76'368.00 18'936.00 134'229.00 CAY 255 Cayman Islands Conf. -

Sports Injuries in Finnish Elite Cross-Country Skiers, Swimmers

A:32 A :24 AA : :24 32 INVALIDISÄÄTIÖINVALIDISÄÄTIÖ • INVALID • ORTON FOUNDATION FOUNDATION INVALIDISÄÄTIÖINVALIDISÄÄTIÖ • INVALID • ORTON FOUNDATION FOUNDATION TieteellinenTieteellinen tutkimus tutkimus ORTONin ORTONin julkaisusarja julkaisusarja ISBN:ISBN 978-952-9657-60-5952-9657-33-1 (paperback) (paperback) PublicationsPublications of the of ORTONthe ORTON Research Research Institute Institute ISBN:ISBN 978-952-9657-61-2952-10-3408-4 (PDF) (pdf) TieteellinenTieteellinen tutkimus tutkimus ORTONin ORTONin julkaisusarja julkaisusarja P.O.B. 29 FIN-00281 HELSINKI FINLAND ISSNISSN 1455-1330 1455-1330 P.O.B. 29 FIN-00281 HELSINKI FINLAND PublicationsPublications of the of theORTON ORTON Research Research Institute Institute Leena | Ristolainen Esa Alakoski SPORTS INJURIES IN FINNISH ELITE Studies on Diamond-like Carbon and Novel Po SPORTS INJURIES IN FINNISH ELITE CROSS-COUNTRY SKIERS, SWIMMERS, RUNNERS LONG-DISTANCE AND SOCCER PLAYERS CROSS-COUNTRY SKIERS, SWIMMERS, StudiesLONG-DISTANCE on Diamond-like RUNNERS Carbon AND and Novel Diamond-likeSOCCER Carbon PLAYERS Polymer Hybrid Coatings Deposited with Filtered Pulsed Arc Discharge Method Esa Alakoski lymer Hybrid Coatings Deposited with Filtered Pulsed Arc Discha Leena Ristolainen r ge Method Helsinki 2012 2006 UnigrafiaYliopistopaino Oy HelsinkiHelsinki 20062012 Sports Injuries in Finnish Elite Cross-Country Skiers, Swimmers, Long-Distance Runners and Soccer Players Leena Ristolainen Department of Health Sciences, University of Jyväskylä, Finland ORTON Orthopaedic Hospital and ORTON Research Institute, ORTON Foundation, Helsinki, Finland ACADEMIC DISSERTATION Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston liikunta- ja terveystieteiden tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston vanhassa juhlasalissa S212 helmikuun 24. päivänä 2012 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences of the University of Jyväskylä, in auditorium S212, on February 24, 2012 at 12 o'clock noon. -

Finland of the Anti-Doping Convention

Strasbourg, 15 June 2005 T-DO (2005) 12 Anti-Doping Convention (T-DO) Project on Compliance with Commitments Respect by Finland of the Anti-Doping Convention Reports by: - Finland - the evaluation team T-DO (2005) 12 2 Table of contents A. Report by Finland ............................................................................................................... 4 1. FOREWORD........................................................................................................................ 4 2. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................ 4 2.1. Sports in Finland.............................................................................................................. 4 2.2 Antidoping work in Finland.............................................................................................. 6 3. COUNCIL OF EUROPE ANTI-DOPING CONVENTION.......................................... 10 3.1. Article 1 Aim of the Convention ................................................................................... 10 3.2 Article 2 Definition and scope of the Convention .......................................................... 11 3.3. Article 3 Domestic co-ordination................................................................................... 12 3.4 Article 4 Measures to restrict the availability and use of banned doping agents and methods................................................................................................................................ -

National Sports Federations (Top Ten Most Popular Olympic Sports)

National Sports Federations (top ten most popular Olympic sports) Coverage for data collection 2015, 2018-2020 Country Name (EN) EU Member States Belgium Royal Belgian Swimming Federation Royal Belgian Athletics Federation Royal Belgian Basketball Federation Belgian Cycling Belgian Equestrian Federation Royal Belgian Football Association Royal Belgian Golf Federation Royal Belgian Hockey Association Royal Belgian Federation of Yachting Royal Belgian Tennis Federation Bulgaria Bulgarian Athletics Federation Bulgarian Basketball Federation Bulgarian Boxing Federation Bulgarian Football Union Bulgarian Golf Association Bulgarian Rhythmic Gymnastics Federation Bulgarian Wrestling Federation Bulgarian Tennis Federation Bulgarian Volleyball Federation Bulgarian Weightlifting Federation Czech Republic Czech Swimming Federation Czech Athletic Federation Czech Basketball Federation Football Association of the Czech Republic Czech Golf Federation Czech Handball Federation Czech Republic Tennis Federation Czech Volleyball Federation Czech Ice Hockey Association Ski Association of the Czech Republic Denmark Danish Swimming Federation Danish Athletic Federation Badminton Denmark Denmark Basketball Federation Danish Football Association Danish Golf Union Danish Gymnastics Federation Danish Handball Federation Danish Tennis Federation Danish Ice Hockey Union Germany German Swimming Association German Athletics Federation German Equestrian Federation German Football Association German Golf Association German Gymnastics Federation German Handball Federation -

FIS Nordic World Ski Championships 2017 Lahti, Finland 22Nd February – 5Th March 2017 2 © and Database Right 2017 Sportcal Global Communications Ltd

GSI Event Study FIS Nordic World Ski Championships 2017 Lahti, Finland 22nd February – 5th March 2017 2 © and database right 2017 Sportcal Global Communications Ltd. All Rights Reserved. GSI EVENT STUDY / FIS NORDIC WORLD SKI CHAMPIONSHIPS 2017 GSI Event Study FIS Nordic World Ski Championships 2017 Lahti, Finland This Event Study is subject to copyright agreements. No part of this Event Study PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER may be reproduced distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means or 2017 BY SPORTCAL GLOBAL stored in any retrieval system of any nature without prior written permission. Application for permission for use of copyright material shall be made to Sportcal COMMUNICATIONS LTD Global Communications Ltd (“Sportcal”). Sportcal has prepared this Event Study using reasonable skill, care and diligence Publisher/Editor for the sole and confidential use of the Finnish Ministry of Culture and Education, GSI Event Study Production Team the Finnish National Olympic Committee, the City of Lahti, Lahti Region and Lahti Mike Laflin Events for the purposes set out in the Event Study and Sportcal does not assume Tim Smith or accept or owe any responsibility or duty of care to any other person. Any use Colin Stewart that a third party makes of this Event Study or reliance thereon or any decision Andrew Horsewood made based on it, is the responsibility of such third party. Matt Finch Callum Murray The Event Study reflects Sportcal’s best judgement in the light of the information Tim Rollason available at the time of its preparation. Sportcal has relied upon the completeness, Beth McGuire accuracy and fair presentation of all the information, data, advice, opinion or Callum Man representations (the “Information”) obtained from public sources and from FIS, Lahti City, Lahti Region, Lahti Events, the Finnish National Olympic Committee and Market Research various third party providers The findings in the Event Study are conditional upon Sportcal India such completeness, accuracy and fair presentation of the Information. -

FIS Congress 2010 FINAL

FÉDÉRATION INTERNATIONALE DE SKI INTERNATIONAL SKI FEDERATION INTERNATIONALER SKI VERBAND CH-3653 Oberhofen (Switzerland), Tel. +41 (33) 244 61 61, Fax +41 (33) 244 61 71 www.fis-ski.com WEDNESDAY, 26 MAY 2010 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FIS MEDIA INFO More than 1’000 participants at the 47 th International Ski Congress in Antalya Oberhofen, 26th May, 2010/-- More than 1’000 participants representing 74 National Member Associations have registered to participate in the 47 th International Ski Congress in Antalya (TUR), from 30 th May to 5 th June 2010. The 2010 Congress will also see a celebration of the 100 th anniversary of the very first International Ski Congress that was held in Christiania (later renamed Oslo), NOR on 18th February 1910. A commemorative book with a review of the first centenary of international skiing will be presented at Antalya. Returning to Turkey for the second time following the FIS Congress in Istanbul in 1988, the international ski family is pleased to follow the invitation of the Turkish Ski Association. As part of the Congress week, the FIS Council as well as the various FIS Technical Committees and Working Groups will convene from 31 st May-3rd June whilst the FIS Congress (General Assembly) itself takes place on 4 th June. The organizers of the FIS Ski Flying World Championships 2014 and the 2015 FIS Alpine, Nordic, Freestyle and Snowboard World Championships will be elected by the FIS Council on Thursday, 3rd June. The candidates (see p.2) will present their projects to all Congress participants from Monday to Wednesday in the customary exhibition and have a final opportunity to present to the Council on Tuesday 1st June as well as to the Technical Committees. -

Costa Navarino

To the INTERNATIONAL SKI FEDERATION - Members of the FIS Council Blochstrasse 2 - National Ski Associations 3653 Oberhofen/Thunersee - Committee Chairladies/Chairmen Switzerland Tel +41 33 244 61 61 Fax +41 33 244 61 71 Oberhofen, 22nd May 2018 Short Summary FIS Council Meetings, 13th to 19th May 2018, Costa Navarino (GRE) Dear Mr. President, Dear Ski Friends, In accordance with art. 32.2 of the FIS Statutes we have pleasure in sending you today the Short Summary of the most important decisions of the FIS Council Meetings that took place in conjunction with the 51st International Ski Congress Costa Navarino (GRE). The main areas addressed during the Meetings of the Council in Costa Navarino were the review of the Congress Book of the 51st International Ski Congress, discussion of the proposals of the National Ski Associations and Technical Committees, as well as the nomination of the FIS Committees for the period 2018 - 2020. The following “short summary of decisions” is in principle limited to Council decisions not directly related to the Congress Agenda. 1. Members present a) The following Council Members were present at the Meetings in Costa Navarino 13th to 17th May 2018: President Gian Franco Kasper, Vice-Presidents Janez Kocijancic, Aki Murasato, Dexter Paine and Sverre Seeberg. Members: Mats Årjes, Andrey Bokarev, Dean Gosper, Alfons Hörmann, Roman Kumpost, Flavio Roda, Eduardo Roldan, Peter Schröcksnadel, Patrick Smith, Martti Uusitalo, Michel Vion, Athletes’ Commission representative Jessica Lindell-Vikarby and the Secretary General Sarah Lewis. Honorary Member: Milan Jirasek b) At the first Meeting of the newly-elected Council for the period 2018 - 2020 on 19th May 2018, the following Members were present: President: Gian Franco Kasper Members: Mats Årjes, Steve Dong Yang, Dean Gosper, Alfons Hörmann, Janez Kocijancic, Roman Kumpost, Aki Murasato, Flavio Roda, Erik Roeste, Peter Schröcksnadel, Patrick Smith, Martti Uusitalo, Eduardo Valenzuela, Michel Vion, Athletes’ Commission representative Konstantin Schad and the Secretary General Sarah Lewis. -

Home Editorial Vuokatti in a Nutshell Xc-Ski

Click here and download Adobe Reader 1 for free. Jyri Pelkonen, Director of the Vuokatti Sport training center. The place to be for professionals ■ Welcome to Vuokatti, one of the world’s finest training facilities for professional athletes involved in Nordic skiing. When it comes to Cross-Country Skiing, Ski Jumping, Nordic Combined, Biathlon and Snowboarding Vuokatti has been Finland’s centre for elite coaching over decades. Our outstanding infrastructure, the highly-professional and devoted staff plus all the gifts nature has provided us with makes Vuokatti the place to be for professionals. But did you know that almost 50 percent of our customers come from abroad and that we are proud to be serving people from over 30 nations? They all know the advantages Vuokatti’s providing them with – be it summer or winter. So you are cordially invited to take a look as well; first in our magazine – and, hopefully, shortly at our premises. Tervetuloa Vuokattiin – welcome to Vuokatti! Click here and download Adobe Reader 2 for free. Here we are Click here and download Adobe Reader 3 for free. Vuokatti in a nutshell ■ Being one of six high performance training centers in Finland, Vuokatti is the only one spe- cializing on Nordic ski sports. It is the perfect training facility all year ’round. Perfect weather conditions in the summer allow athletes to improve their physical skills for the winter season. From the beginning of October we are able to provide athletes with man-made snow, being one of the first places in the world offering snow-covered outdoor cross-country ski tracks, and a biathlon shooting range. -

Women and Sport Progress Report

From Windhoek From to Montreal: and Women Sport Progress Report 1998-2002 For the Group (IWG) Working International From Windhoek to Montreal International Working Group on Women and Sport Women and Sport Progress Report 1998-2002 Anita White & Deena Scoretz For the International Working Group on women and Sport (IWG) Contact information for the IWG Secretariat from 2002-2006: IWG Secretariat P.O. Box 1111-HHD, Tokyo-Chiyoda Central Station, Tokyo 100-8612 Japan Tel: +81 3 5446 8983 Fax: +81 3 5446 8942 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.iwg-gti.org Photos used in this document have been provided by the following: Aerobics for Pregnant Women Program, Zimbabwe Bernard Brault Bev Smith Canada Games Council and Concepts to Applause Canadian Paralympic Committee Caribbean Coaching Certification Program, St. Lucia Commonwealth Games Canada - International Sport Development K. Terauds Martin Charboneau Sayuri Inoue (JWS) Singapore Sports Council Smith College (USA) WomenSports Federation (I. R. of Iran) IBSN 0-9730719-0-7 This document is also available in French and Spanish: De Windhoek à Montréal : Rapport d'étape sur les femmes et le sport, 1998-2002 De Windhoek a Montreal: Informe de Avance sobre la Mujer y el Deporte, 1998-2002 © International Working Group on Women and Sport, 2002 From Windhoek to Montreal International Working Group on Women and Sport Women and Sport Progress Report 1998-2002 Anita White & Deena Scoretz For the International Working Group (IWG) Table of Contents Acknowledgements . .v Message from the Co-Chairs of the International Working Group on Women and Sport . .vii Introduction . .ix Chapter 1: Background and Context A) First world conference in Brighton, UK in 1994 .