Russ Jones 124 Chaney Sr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eerie Archives: Volume 16 Free

FREE EERIE ARCHIVES: VOLUME 16 PDF Bill DuBay,Louise Jones,Faculty of Classics James Warren | 294 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616554002 | English | Milwaukee, United States Eerie (Volume) - Comic Vine Gather up your wooden stakes, your blood-covered hatchets, and all the skeletons in the darkest depths of your closet, and prepare for a horrifying adventure into the darkest corners of comics history. This vein-chilling second volume showcases work by Eerie Archives: Volume 16 of the best artists to ever work in the comics medium, including Alex Toth, Gray Morrow, Reed Crandall, John Severin, and others. Grab your bleeding glasses and crack open this fourth big volume, collecting Creepy issues Creepy Archives Volume 5 continues the critically acclaimed series that throws back the dusty curtain on a treasure trove of amazing comics art and brilliantly blood-chilling stories. Dark Horse Comics continues to showcase its dedication to publishing the greatest comics of all time with the release of the sixth spooky volume Eerie Archives: Volume 16 our Creepy magazine archives. Creepy Archives Volume 7 collects a Eerie Archives: Volume 16 array of stories from the second great generation of artists and writers in Eerie Archives: Volume 16 history of the world's best illustrated horror magazine. As the s ended and the '70s began, the original, classic creative lineup for Creepy was eventually infused with a slew of new talent, with phenomenal new contributors like Richard Corben, Ken Kelly, and Nicola Cuti joining the ranks of established greats like Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Al Williamson. This volume of the Creepy Archives series collects more than two hundred pages of distinctive short horror comics in a gorgeous hardcover format. -

10221 GJR31 CA Journalism in the Media and Communications

General Certificate of Secondary Education Journalism in the Media and Communications Industry (JMC) Controlled Assessment Task Unit 3: Broadcast Media and Communications Part 1: News Bulletin [GJR31] VALID FROM 1st SEPTEMBER 2015 INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES UNIT 3 TASK INTRODUCTION The overall purpose of the Unit 3 task is to produce two broadcast scripts: • 1 script for a 3-minute news bulletin (Part 1); and • 1 script for a 2-minute news package (Part 2). Format The broadcast media format you will be working in for this task will be: Northern Ireland regional radio – for a public service broadcast at 5 pm. Instructions continue on pages 2 and 3. Candidates’ work to be submitted May 2016 10221 PART 1: NEWS BULLETIN The material contained in this booklet is for Part 1 of the Unit 3 Task. On pages 4 to 21 you will fi nd source material for a 5.00 pm news bulletin. The material contains 14 stories from which you will select the content for your 3-minute news bulletin. Stories are taken from a number of different dates and sources to provide suffi cient variety of material for you to choose from. The source of each story is specifi ed for you to help your background research. The date of each story falls within the month of December 2014. For the purposes of this task, all stories should be treated as though they have occurred on the same day. You may choose your own date. Timescale You must produce a script for the 3-minute news bulletin within 7 weeks of receiving this material. -

APPEARANCES of HORROR HOSTS and HOSTESSES in MAGAZINES Article by Jim Knusch

APPEARANCES OF HORROR HOSTS AND HOSTESSES IN MAGAZINES Article by Jim Knusch Zach postage stamp by Jim Mattern Premier admat of SHOCK! in TV Guide In the 'golden age' the late 1950s and early 1960s of monster fandom a lot was happening. A generation weaned on television and made fearful of the evils of communism and the reality of nuclear war was coming of age. That is, they were into their teens. Both the USA and Great Britain began to resurrect (in more ways than one) and breathe a new life into many of these classic monsters in updated productions for the big screen. These new offerings were embellished with color and gore. Life magazine of Nov 11, 1957 featured a two page spread promoting new and upcoming horror and scifi releases from AmericanInternational Pictures. Big screen horror and monsters were in. Vintage horror movies, especially of the 1930s, were finding a welcome audience on the tube. This acceptance was so strong that it led to a repackaging of select titles being syndicated and offered weekly under the title of SHOCK! The SHOCK! TV package was seen in some areas as SHOCK THEATRE, NIGHTMARE and HOUSE OF HORROR. As was suggested by the SHOCK! promo book, some of these were hosted locally by bizarre personalities. These personalities in themselves became phenomenally popular. This was evidenced by major pictorial articles in national magazines, hundreds of fan clubs, the marketing of premiums andmost importantlyhigh TV ratings. To the teenage fan caught up in all of this a trip to the local newsstand would result in the purchase of a comic book, a humor magazine or an occasional 'Tales of the Crypt' type of periodical that was somewhere in between a comic book and pulp magazine. -

Tom Baker Is Back As the Doctor for the Romance of Crime and the English Way of Death

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES GO FOURTH! TOM BAKER IS BACK AS THE DOCTOR FOR THE ROMANCE OF CRIME AND THE ENGLISH WAY OF DEATH ISSUE 71 • JANUARY 2015 WELCOME TO BIG FINISH! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio dramas and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Big Finish… Subscribers get more We love stories. at bigfinish.com! Our audio productions are based on much- If you subscribe, depending on the range you loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers and of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a Survivors as well as classic characters such as bonus release, downloadable audio readings of Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera new short stories and discounts. and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless and The Adventures of Bernice www.bigfinish.com Summerfield. You can access a video guide to the site at We publish a growing number of books (non- www.bigfinish.com/news/v/website-guide-1 fiction, novels and short stories) from new and established authors. WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH /THEBIGFINISH VORTEX MAGAZINE PAGE 3 Sneak Previews & Whispers Editorial HEN PLANNING ahead for this month’s issue of W Vortex, David Richardson suggested that I might speak to Tom Baker, to preview his new season of adventures, and the Gareth Roberts novel adaptations. That was one of those moments when excitement and fear hit me in equal measure. I mean, this is Tom Baker! TOM BAKER! I was born 11 days after he made his first appearance in Planet of the Spiders, so growing up, he was my Doctor. -

SLAV-T230 Vampire F2019 Syllabus-Holdeman-Final

The Vampire in European and American Culture Dr. Jeff Holdeman SLAV-T230 11498 (SLAV) (please call me Jeff) SLAV-T230 11893 (HHC section) GISB East 4041 Fall 2019 812-855-5891 (office) TR 4:00–5:15 pm Office hours: Classroom: GA 0009 * Tues. and Thur. 2:45–3:45 pm in GISB 4041 carries CASE A&H, GCC; GenEd A&H, WC * and by appointment (just ask!!!) * e-mail me beforehand to reserve a time * It is always best to schedule an appointment. [email protected] [my preferred method] 812-335-9868 (home) This syllabus is available in alternative formats upon request. Overview The vampire is one of the most popular and enduring images in the world, giving rise to hundreds of monster movies around the globe every year, not to mention novels, short stories, plays, TV shows, and commercial merchandise. Yet the Western vampire image that we know from the film, television, and literature of today is very different from its eastern European progenitor. Nina Auerbach has said that "every age creates the vampire that it needs." In this course we will explore the eastern European origins of the vampire, similar entities in other cultures that predate them, and how the vampire in its look, nature, vulnerabilities, and threat has changed over the centuries. This approach will provide us with the means to learn about the geography, village and urban cultures, traditional social structure, and religions of eastern Europe; the nature and manifestations of Evil and the concept of Limited Good; physical, temporal, and societal boundaries and ritual passage that accompany them; and major historical and intellectual periods (the settlement of Europe, the Age of Reason, Romanticism, Neo-classicism, the Enlightenment, the Victorian era, up to today). -

Issues of Gender in Muscle Beach Party (1964) Joan Ormrod, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-space: Manchester Metropolitan University's Research Repository Issues of Gender in Muscle Beach Party (1964) Joan Ormrod, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK Muscle Beach Party (1964) is the second in a series of seven films made by American International Pictures (AIP) based around a similar set of characters and set (by and large) on the beach. The Beach Party series, as it came to be known, rode on a wave of surfing fever amongst teenagers in the early 1960s. The films depicted the carefree and affluent lifestyle of a group of middle class, white Californian teenagers on vacation and are described by Granat as, "…California's beautiful people in a setting that attracted moviegoers. The films did not 'hold a mirror up to nature', yet they mirrored the glorification of California taking place in American culture." (Granat, 1999:191) The films were critically condemned. The New York Times critic, for instance, noted, "…almost the entire cast emerges as the dullest bunch of meatballs ever, with the old folks even sillier than the kids..." (McGee, 1984: 150) Despite their dismissal as mere froth, the Beach Party series may enable an identification of issues of concern in the wider American society of the early sixties. The Beach Party films are sequential, beginning with Beach Party (1963) advertised as a "musical comedy of summer, surfing and romance" (Beach Party Press Pack). Beach Party was so successful that AIP wasted no time in producing six further films; Muscle Beach Party (1964), Pajama Party (1964) Bikini Beach (1964), Beach Blanket Bingo (1965) How to Stuff a Wild Bikini (1965) and The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini (1966). -

John Zacherle, One of the First of the Late-Night Television Horror-Movie

OBITUARIES 10/29/2016 By WILLIAM GRIMES John Zacherle as the playfully spooky Zacherley in the 1950s. Louis Nemeth John Zacherle, one of the first of the late-night television horror-movie hosts, who played a crypt-dwelling undertaker with a booming graveyard laugh on stations in Philadelphia and New York in the late 1950s and early ’60s, died on Thursday at his home in Manhattan. He was 98. His death was announced by friends and a fan website. Mr. Zacherle, billed as Zacherley in New York, was not the first horror host — that honor goes to Maila Nurmi, the Finnish-born actress who began camping it up as Vampira on KABC-TV in Los Angeles in 1954 — but he was the most famous, inspiring a host of imitators at local stations around the country. As Roland in Philadelphia (pronounced ro-LAHND) and Zacherley in New York, he added grisly theatrics and absurdist humor to the entertainment on offer, which more often than not was less than Oscar quality. He became a cult figure, making star appearances at horror conventions across the Northeast. Dressed in a long black frock coat decorated with a large medal from the government of Transylvania, Roland introduced, and interrupted, the evening’s film with comic bits involving characters who existed only as props in his crypt-cum-laboratory. John Zacherle in 2012. Julie Glassberg for The New York Times There was My Dear, his wife, recumbent in a coffin with a stake in her heart, and his son, Gasport, a series of moans within a potato bag suspended from the ceiling. -

Rosemary Ellen Guiley

vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page i The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page ii The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS Rosemary Ellen Guiley FOREWORD BY Jeanne Keyes Youngson, President and Founder of the Vampire Empire The Encyclopedia of Vampires, Werewolves, and Other Monsters Copyright © 2005 by Visionary Living, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guiley, Rosemary. The encyclopedia of vampires, werewolves, and other monsters / Rosemary Ellen Guiley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4684-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4381-3001-9 (e-book) 1. Vampires—Encyclopedias. 2. Werewolves—Encyclopedias. 3. Monsters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF1556.G86 2004 133.4’23—dc22 2003026592 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

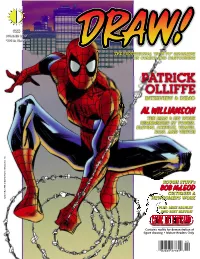

Patrick Olliffe Interview & Demo Al Williamson the Man & His Work Remembered by Torres, Blevins, Schultz, Yeates, Ross, and Veitch

#23 SUMMER 2012 $7.95 In The US THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS AND CARTOONING PATRICK OLLIFFE INTERVIEW & DEMO AL WILLIAMSON THE MAN & HIS WORK REMEMBERED BY TORRES, BLEVINS, SCHULTZ, YEATES, ROSS, AND VEITCH ROUGH STUFF’s BOB McLEOD CRITIQUES A Spider-Man TM Spider-Man & ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc. NEWCOMER’S WORK PLUS: MIKE MANLEY AND BRET BLEVINS’ Contains nudity for demonstration of figure drawing • Mature Readers Only 0 2 1 82658 27764 2 THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS & CARTOONING WWW.DRAW-MAGAZINE.BLOGSPOT.COM SUMMER 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOL. 1, NO. 23 Editor-in-Chief • Michael Manley Designer • Eric Nolen-Weathington PAT OLLIFFE Publisher • John Morrow Mike Manley interviews the artist about his career and working with Al Williamson Logo Design • John Costanza 3 Copy-Editing • Eric Nolen- Weathington Front Cover • Pat Olliffe DRAW! Summer 2012, Vol. 1, No. 23 was produced by Action Planet, Inc. and published by TwoMorrows Publishing. ROUGH CRITIQUE Michael Manley, Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. Bob McLeod gives practical advice and Editorial address: DRAW! Magazine, c/o Michael Manley, 430 Spruce Ave., Upper Darby, PA 19082. 22 tips on how to improve your work Subscription Address: TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Dr., Raleigh, NC 27614. DRAW! and its logo are trademarks of Action Planet, Inc. All contributions herein are copyright 2012 by their respective contributors. Action Planet, Inc. and TwoMorrows Publishing accept no responsibility for unsolicited submissions. All artwork herein is copyright the year of produc- THE CRUSTY CRITIC tion, its creator (if work-for-hire, the entity which Jamar Nicholas reviews the tools of the trade. -

Download Complete-Skywald-Checklist

MAY JUL SEP http://w w w .enjolrasw orld.com/Richard%20Arndt/The%20Complete%20Skyw ald%20Checklist.htmGo Close 44 captures 16 21 Jan 05 - 13 Feb 15 2010 Help2011 2012 Last updated 2 Dec. 2010. The latest version of this document can always be found at www.enjolrasworld.com. See last page for legal & © information. Additions? Corrections? Contact Richard J. Arndt: [email protected]. The Complete Skywald Checklist This index is as complete as possible given Skywald’s custom of often dropping credits off stories, hiding credits in the art of the story {mostly under Hewetson’s reign—in windowsills, gables, panel borders, as debris, etc.}, the heavy use of pseudomyns & single names and the miscrediting of stories to the wrong artist. Many of the mysteries regarding credits have been solved by access to Al Hewetson’s notes & checklists as well as the extensive aid of Christos N. Gage. Check out the end of the bibliography for interviews with Al Hewetson, Ed Fedory, Augustine Funnell & Maelo Cintron. You’ll be glad you did! Nightmare 1. cover: Brendan Lynch? (Dec. 1970) 1) The Pollution Monsters [Mike Friedrich/Don Heck & Mike Esposito] 10p 2) Master Of The Dead! [?/Martin Nodell &Vince Alascia] 6p [reprint from Eerie #14, Avon, 1954] 3) Dance Macabre [?/? & Bill Everett?] 6p [reprint from the 1950s] 4) Orgy Of Blood [Ross Andru & Mike Esposito/Ross Andru & Mike Esposito] 8p 5) A Nightmare Pin-Up [Bill Everett] 1p 6) The Skeletons Of Doom! [Art Stampler/Bill Everett] 3p [text story] 7) Help Us To Die! [?/?] 6p [reprint from the 1950s] 8) The Thing From The Sea! [?/Wally Wood & Mike Esposito?] 7p [reprint from Eerie #2, Avon, 1951] 9) The Creature Within! [?/?] 3p [reprint from the1950s] 10) The Deadly Mark Of The Beast! [Len Wein/Syd Shores & Tom Palmer] 8p open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com 11) Nightmares’s Nightmail [letters’ page] 1p Notes: Publisher: Sol Brodsky & Israel Waldman. -

BERNARD BAILY Vol

Roy Thomas’ Star-Bedecked $ Comics Fanzine JUST WHEN YOU THOUGHT 8.95 YOU KNEW EVERYTHING THERE In the USA WAS TO KNOW ABOUT THE No.109 May JUSTICE 2012 SOCIETY ofAMERICA!™ 5 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 Art © DC Comics; Justice Society of America TM & © 2012 DC Comics. Plus: SPECTRE & HOUR-MAN 6 2 8 Co-Creator 1 BERNARD BAILY Vol. 3, No. 109 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck AT LAST! Comic Crypt Editor ALL IN Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll COLOR FOR $8.95! Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Proofreader Rob Smentek Cover Artist Contents George Pérez Writer/Editorial: An All-Star Cast—Of Mind. 2 Cover Colorist Bernard Baily: The Early Years . 3 Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Ken Quattro examines the career of the artist who co-created The Spectre and Hour-Man. “Fairytales Can Come True…” . 17 Rob Allen Roger Hill The Roy Thomas/Michael Bair 1980s JSA retro-series that didn’t quite happen! Heidi Amash Allan Holtz Dave Armstrong Carmine Infantino What If All-Star Comics Had Sported A Variant Line-up? . 25 Amy Baily William B. Jones, Jr. Eugene Baily Jim Kealy Hurricane Heeran imagines different 1940s JSA memberships—and rivals! Jill Baily Kirk Kimball “Will” Power. 33 Regina Baily Paul Levitz Stephen Baily Mark Lewis Pages from that legendary “lost” Golden Age JSA epic—in color for the first time ever! Michael Bair Bob Lubbers “I Absolutely Love What I’m Doing!” . -

See Page 19 for Details!!

RRegionegion 1177 SSummit/Marineummit/Marine MMusteruster MMayay 220-220-22 128 DDenver,enver, CColoradoolorado APR 2005/ MAY 2005 SSeeee ppageage 1199 fforor ddetails!!etails!! USS Ark Angel’s CoC and Marines’ Fall Muster ’04 see pages 19 & 20 for full story! “Save Star Trek” Rally see page 28 for more great pics! Angeles member Jon Lane with the “Enterprise” writing staff. From left to right: Jon Lane, “Enterprise” writers Judith and Garfi eld Reese-Stevens, and producer Mike Sussman. Many of the the show’s production staff wandered out to see the protest and greet the fans. USPS 017-671 112828 112828 STARFLEET Communiqué Contents Volume I, No. 128 Published by: FROM THE EDITOR 2 STARFLEET, The International FRONT AND CENTER 3 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. EC/AB SUMMARY 3 102 Washington Drive VICARIOUS CHOC. SALUTATIONS 4 Ladson, SC 29456 COMM STATIC 4 Kneeling: J.R. Fisher THE TOWAWAY ZONE 5 (left to right) 1st Row: Steve Williams, Allison Silsbee, Lauren Williams, Alastair Browne, The SHUTTLEBAY 6 Amy Dejongh, Spring Brooks, Margaret Hale. 2nd Row: John (boyfriend of Allison), Katy Publisher: Bob Fillmore COMPOPS 6 McDonald, Nathan Wood, Larry Pischke, Elaine Pischke, Brad McDonald, Dawn Silsbee. Editor in Chief: Wendy Fillmore STARFLEET Flag Promotions 7 Layout Editor: Wendy Fillmore Fellowship...or Else! 7 3rd Row: Colleen Williams, Jonathan Williams. Graphics Editor: Johnathan Simmons COMMANDANTS CORNER 8 Submissions Coordinator: Wendy Fillmore SFI Academy Graduates 8 Copy Editors: Gene Adams, Gabriel Beecham, New Chairman Sought for ASDB! 9 Kimberly Donohoe, Michael Klufas, Tracy Lilly, Star Trek Encyclopedia Project 9 STARFLEET Finances 10 Bruce Sherrick EDITORIALS 11 Why I Stopped Watching..