Sam Katzman's Switchblade Calypso Bop Reefer Madness Swamp Girl Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Gene Barge

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Gene Barge Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Barge, Gene Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Gene Barge, Dates: January 20, 2012 Bulk Dates: 2012 Physical 6 uncompressed MOV digital video files (2:51:59). Description: Abstract: Saxophonist, songwriter, and music producer Gene Barge (1926 - ) played on Chuck Willis’ pop hit, “C.C. Rider,” co-wrote with Gary U.S. Bonds “Quarter to Three” and received a Grammy Award for co-producing Natalie Cole’s “Sophisticated Lady.” Barge was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on January 20, 2012, in Chicago, Illinois. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2012_043 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Saxophonist, music producer and song writer Gene “Daddy G” Barge was born in Norfolk, Virginia on August, 9 1926. He graduated from Booker T. Washington High School and played clarinet in the school band. Barge then attended West Virginia State College where he first majored in architecture, but quickly switched to music because of his interest in the saxophone. After receiving his B.A. degree from West Virginia State College in 1950, Barge returned to Norfolk, Virginia and played with a number of bands and singing groups including the Griffin Brothers and the Five Keys. In 1955, Barge recorded his first saxophone instrumentals entitled “Country” and “Way Down Home” on Chess Records’ Checker Label. He taught music at Suffolk High School while playing and singing in bands and touring with both Ray Charles and the Philadelphia vocal group The Turbans. -

Issues of Gender in Muscle Beach Party (1964) Joan Ormrod, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-space: Manchester Metropolitan University's Research Repository Issues of Gender in Muscle Beach Party (1964) Joan Ormrod, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK Muscle Beach Party (1964) is the second in a series of seven films made by American International Pictures (AIP) based around a similar set of characters and set (by and large) on the beach. The Beach Party series, as it came to be known, rode on a wave of surfing fever amongst teenagers in the early 1960s. The films depicted the carefree and affluent lifestyle of a group of middle class, white Californian teenagers on vacation and are described by Granat as, "…California's beautiful people in a setting that attracted moviegoers. The films did not 'hold a mirror up to nature', yet they mirrored the glorification of California taking place in American culture." (Granat, 1999:191) The films were critically condemned. The New York Times critic, for instance, noted, "…almost the entire cast emerges as the dullest bunch of meatballs ever, with the old folks even sillier than the kids..." (McGee, 1984: 150) Despite their dismissal as mere froth, the Beach Party series may enable an identification of issues of concern in the wider American society of the early sixties. The Beach Party films are sequential, beginning with Beach Party (1963) advertised as a "musical comedy of summer, surfing and romance" (Beach Party Press Pack). Beach Party was so successful that AIP wasted no time in producing six further films; Muscle Beach Party (1964), Pajama Party (1964) Bikini Beach (1964), Beach Blanket Bingo (1965) How to Stuff a Wild Bikini (1965) and The Ghost in the Invisible Bikini (1966). -

Stage Door Swings Brochure

. 0 A G 6 E C R 2 G , O 1 FEATURING A H . T T D C I O I S F A N O E O A P T B R I . P P G The Palladium Big 3 Orchestra S M . N N R U O E O Featuring the combined orchestras N P L of Tito Puente, Machito and Tito Rodriguez presents Manteca - The Afro-Cuban Music of The Dizzy Gillespie Big Band FROM with special guest Candido CUBAN FIRE Brazilliance featuring TO SKETCHES Bud Shank OF SPAIN The Music of Chico O’ Farrill Big Band Directed by Arturo O’Farrill Bill Holman Band- Echoes of Aranjuez 8 3 0 Armando Peraza 0 - 8 Stan Kenton’s Cuban Fire 0 8 0 Viva Tirado- 9 e The Gerald Wilson Orchestra t A u t C i Jose Rizo’s Jazz on , t s h the Latin Side All-Stars n c I a z Francisco Aguabella e z B a Justo Almario J g n s o Shorty Rogers Big Band- e l L , e Afro-Cuban Influence 8 g 3 n Viva Zapata-The Latin Side of 0 A 8 The Lighthouse All-Stars s x o o L Jack Costanzo B . e O h Sketches of Spain . P T The classic Gil Evans-Miles Davis October 9-12, 2008 collaboration featuring Bobby Shew Hyatt Regency Newport Beach Johnny Richards’ Rites of Diablo 1107 Jamboree Road www.lajazzinstitute.org Newport Beach, CA The Estrada Brothers- Tribute to Cal Tjader about the LOS PLATINUM VIP PACKAGE! ANGELES The VIP package includes priority seats in the DATES HOW TO amphitheater and ballroom (first come, first served JAZZ FESTIVAL | October 9-12, 2008 PURCHASE TICKETS basis) plus a Wednesday Night bonus concert. -

88-Page Mega Version 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010

The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! 88-PAGE MEGA VERSION 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 COMBINED jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! INDEX 2017 Gift Guide •••••• 3 2016 Gift Guide •••••• 9 2015 Gift Guide •••••• 25 2014 Gift Guide •••••• 44 2013 Gift Guide •••••• 54 2012 Gift Guide •••••• 60 2011 Gift Guide •••••• 68 2010 Gift Guide •••••• 83 jazz &blues report jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com 2017 Gift Guide While our annual Gift Guide appears every year at this time, the gift ideas covered are in no way just to be thought of as holiday gifts only. Obviously, these items would be a good gift idea for any occasion year-round, as well as a gift for yourself! We do not include many, if any at all, single CDs in the guide. Most everything contained will be multiple CD sets, DVDs, CD/DVD sets, books and the like. Of course, you can always look though our back issues to see what came out in 2017 (and prior years), but none of us would want to attempt to decide which CDs would be a fitting ad- dition to this guide. As with 2016, the year 2017 was a bit on the lean side as far as reviews go of box sets, books and DVDs - it appears tht the days of mass quantities of boxed sets are over - but we do have some to check out. These are in no particular order in terms of importance or release dates. -

Big Al's R&B, 1956-1959

The R & B Book S7 The greatest single event affecting the integration of rhythm and blues music Alone)," the top single of 195S, with crossovers "(YouVe Got! The Magic Touch" with the pop field occurred on November 2, 1355. On that date. Billboard (No. 4), "The Great Pretender" and "My Prayer" (both No. It. and "You'll Never magazine expanded its pop singles chart from thirty to a hundred positions, Never Know" b/w "It Isn't Bight" (No. 14). Their first album "The Platters" naming it "The Top 100." In a business that operates on hype and jive, a chart reached No. 7 on Billboard's album chart. position is "proof of a record's strength. Consequently, a chart appearance, by Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, another of the year's consistent crossover itself, can be a promotional tool With Billboard's expansion to an extra seventy artists, tasted success on their first record "Why Do Fools Fall In Love" (No. 71, positions, seventy extra records each week were documented as "bonifide" hits, then followed with "I Want You To Be My Girl" (No. 17). "I Promise To and 8 & B issues helped fill up a lot of those extra spaces. Remember" (No. 57), and "ABCs Of Love" (No. 77). (Joy & Cee-BMI) Time: 2:14 NOT FOR S»U 45—K8592 If Um.*III WIlhORtnln A» Unl» SIM meant tea M. bibUnfmcl him a> a ronng Bnc«rtal««r to ant alonic la *n«l«y •t*r p«rjform«r. HI* » T«»r. Utcfo WIIII* Araraa ()•• 2m«B alnft-ng Th« WorM** S* AtUX prafautonaiiQ/ for on manr bit p«» throoghoQC ih« ib« SaiMt fonr Tun Faaturing coont^T and he •llhan«h 6. -

U Clinton County News Dewitt Chief Resigns

A- U Clinton County News 15 Cents ST JOHNS, MICHIGAN 48879 117th Year Vol. 52 34 Pages May 2,1973 DeWitt finder \ Q-There is a blind couple in St Johns 1 who used to go bowling in Lansing last Chief year, but were unable to continue because they couldn't find a ride to the' bowling alley. This seems a shame. Can Fact Finder help locate a ride for them? A-We'll sure try. We contacted them, and learned that they would like to join a league which bowls on Friday nights resigns from 6-10 pm in Lansing, beginning right after Labor Day. If there is ' anyone interested, or any group, in DEWITT -- In an April 23 letter to furnishing transportation for the Daniel Elliott, DeWitt city ad would be temporary until the new fiscal ministrator, DeWitt Police Chief year. As far as I'm concerned, I was couple, please contact Fact Finder at mis-led." 224-2361. We will get in touch with them. Charles Anderson announced his 1 resignation, /stating in part, ".. .the Anderson further stated that he was present administration has made it led to believe that the city had no in impossible to.continue to be employed tention of not re-hiring him as chief. County by the city of DeWitt." He indicated the Police Board gave him a list of approximately a half-dozen Appearing before a near capacity crowd at Rodney B. Wilson Junior High last Wednesday night was the Ahrensburg Mayor Raymond DeWitt told the County News Friday that decision had items they felt should be done by the Youth Orchestra from Ahrensburg, Germany. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Group Tries to Revive Once-Popular Royal Peacock Club

INTOWN EXTRA, FEBRUARYzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaYWVUTSRPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA 7, 1985 The Royal Peacock was given birth in 1949 when a black businesswoman, Carrie "Mama" Cunningham, shown here, Neon signs tsrlifebaWSstill bill the Royal Peacock on Au- purchased what waa then the Top Hat Club from thtee black burn Avenue ae "Atlanta's Club Beautiful." businessmen and gave the club its present name. The current managers are trying to revive the Group tries to revive once-popular Royal Peacock club Blayton, 60, who also served as Bland, Jimmy Reed, Brook Benton, Ambassadors, Riggins "Red " McAl- when programs at the club will be lister and his band, Levi Mann and By Pete Scott held to support youth programs in bookkeeper for the club. Arthur Prysock, Chuck Willis, the Staff Writer "We had a regular chorus line Isley Brothers, Temptations, Su- his band, Lawrence Walker, Chick the nearby Grady Homes public Webb and his band, and Tiny Brad- housing complex. with several local bands. Most of premes, Spinners, Dells, Four Tops, The Royal Peacock, billed as the girls in the chorus line had the Miracles, Gladys Knight and the shaw and his band. "Atlanta's club beautiful," once was Braswell added that with the The Peacock, at 185% Auburn, help of promoter Smith, his group high yellow or mulatto appearance." Pips and many others, the Peacock the show place of Auburn Avenue. With performing artists such as helped bolster Auburn Avenue's just off Piedmont Avenue, is a far Before that, when it was known as hopes to bring in live entertainment cry from the glitter of days gone and have talent shows and dances to Stevie Wonder, Miles Davis, Oscar glamour. -

The R&B Pioneers Series

The Great R&B Files (# 11 of 12) Updated March 1, 2019 The R&B Pioneers Series Compiled by Claus Röhnisch Special Supplement: Top 30 Favorites - featuring the Super Legends’ Ultimate CD compilations, their very first albums, * and ± .. plus their most classic singles. Top Rhythm & Blues Records - The Top R&B Hits from 30 classic years of Rhythm & Blues THE Blues Giants of the 1950s THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden ‘50s Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ‘n’ Roll Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons The True R&B Pioneers – Twelve Hit-Makers of the Early Years Predecessors of the Soul Explosion in the 1960s Clyde McPhatter – The Original Soul Star The John Lee Hooker Session Discography The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters Those Hoodlum Friends – The Coasters Page 1 (94) THE R&B PIONEERS Series - Volume Eleven of twelve Compiled by Claus Röhnisch The R&B Pioneers Series: find them all at The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info (try the links her on the next page for youtube) Vol 1. Top Rhythm & Blues Records The Top R&B Hits from 30 classic years of Rhythm & Blues Vol 2. The John Lee Hooker Session Discography Complete discography, year-by-year recap, CD-Guide, and more John Lee Hooker – The World’s Greatest Blues Singer Vol 3. The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll Todd Baptista’s great Essay on The Coasters, completed with Singles Discography, Chart Hits, Session Discography, and much more Vol 4. -

Bob Gordon Discography

BOB GORDON DISCOGRAPHY BOB GORDON RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS Bob Gordon was born in St. Louis, Missouri, June 11, 1928. He passed away in a car accident between Hollywood and San Diego, CA., August 28, 1955 by Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2019 Bob Gordon DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 INTERNAL INFORMATION Colour markings for physical position: IKEA-boxes with Bob Gordon = GREEN IKEA-boxes with Lars Gullin = YELLOW IKEA-boxes with Gerry Mulligan = BLUE Shelves = ORANGE Cupboard = RED Bob played tenor sax with: Shorty Sherock (1946) Alvino Ray (1948-1951) Billy May (1952) Horace Heidt (1952-1953) George Redman (1954) Search for LPs/CDs: GNP J.S.L.P. 50.042: "Maynard Ferguson - Dimensions" (Trip Jazz LP available) EMArcy LP #MG 36044: "Lyle Murphy: Four saxophones in twelwe tones" (10" LP 1955) Mercury CD EJD-1016: COMPACT JAZZ - Maynard Ferguson with Bob Gordon (released in Japan 1989) EMArcy CD #3071: "Introducing Bob Gordon" Bob Gordon DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 2 Abbreviations used in this discography acc accordion mda mandola arr arranger mdln mandolin as alto saxophone mel melodica b bass (contrabass or double bass) mgs Moog synthesizer b-cl bass clarinet oboe oboe b-tb bass trombone oca ocarina b-tp bass trumpet org organ bars baritone saxophone p piano bgs bongos panfl pan flute bjo banjo perc percussion bnd bandoneon saxes saxophones bs bass saxophone sop soprano saxophone bsn bassoon st-d steel drums cgs -

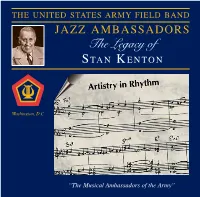

The Legacy of S Ta N K E N to N

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND JAZZ AMBASSADORS The Legacy of S TA N K ENTON Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” he Jazz Ambassadors is the Concerts, school assemblies, clinics, T United States Army’s premier music festivals, and radio and televi- touring jazz orchestra. As a component sion appearances are all part of the Jazz of The United States Army Field Band Ambassadors’ yearly schedule. of Washington, D.C., this internation- Many of the members are also com- ally acclaimed organization travels thou- posers and arrangers whose writing helps sands of miles each year to present jazz, create the band’s unique sound. Concert America’s national treasure, to enthusi- repertoire includes big band swing, be- astic audiences throughout the world. bop, contemporary jazz, popular tunes, The band has performed in all fifty and dixieland. states, Canada, Mexico, Europe, Ja- Whether performing in the United pan, and India. Notable performances States or representing our country over- include appearances at the Montreux, seas, the band entertains audiences of all Brussels, North Sea, Toronto, and New- ages and backgrounds by presenting the port jazz festivals. American art form, jazz. The Legacy of Stan Kenton About this recording The Jazz Ambassadors of The United States Army Field Band presents the first in a series of recordings honoring the lives and music of individuals who have made significant contri- butions to big band jazz. Designed primarily as educational resources, these record- ings are a means for young musicians to know and appreciate the best of the music and musicians of previous generations, and to understand the stylistic developments leading to today’s litera- ture in ensemble music. -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films.