Folds, Floods, and Fine Wine: Geologic Influences on the Terroir of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terroir of Wine (Regionality)

3/10/2014 A New Era For Fermentation Ecology— Routine tracking of all microbes in all places Department of Viticulture and Enology Department of Viticulture and Enology Terroir of Wine (regionality) Source: Wine Business Monthly 1 3/10/2014 Department of Viticulture and Enology Can Regionality Be Observed (Scientifically) by Chemical/Sensory Analyses? Department of Viticulture and Enology Department of Viticulture and Enology What about the microbes in each environment? Is there a “Microbial Terroir” 2 3/10/2014 Department of Viticulture and Enology We know the major microbial players Department of Viticulture and Enology Where do the wine microbes come from? Department of Viticulture and Enology Methods Quality Filtration Developed Pick Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) Nick Bokulich Assign Taxonomy 3 3/10/2014 Department of Viticulture and Enology Microbial surveillance: Next Generation Sequencing Extract DNA >300 Samples PCR Quantify ALL fungal and bacterial populations in ALL samples simultaneously Sequence: Illumina Platform Department of Viticulture and Enology Microbial surveillance: Next Generation Sequencing Department of Viticulture and Enology Example large data set: Bacterial Profile 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Winery Differences Across 300 Samplings 4 3/10/2014 Department of Viticulture and Enology Microbial surveillance process 1. Compute UniFrac distance (phylogenetic distance) between samples 2. Principal coordinate analysis to compress dimensionality of data 3. Categorize by metadata 4. Clusters represent samples of similar phylogenetic -

Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Open File Report

RECONNAISSANCE SURFICIAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING OF THE LATE CENOZOIC SEDIMENTS OF THE COLUMBIA BASIN, WASHINGTON by James G. Rigby and Kurt Othberg with contributions from Newell Campbell Larry Hanson Eugene Kiver Dale Stradling Gary Webster Open File Report 79-3 September 1979 State of Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Olympia, Washington CONTENTS Introduction Objectives Study Area Regional Setting 1 Mapping Procedure 4 Sample Collection 8 Description of Map Units 8 Pre-Miocene Rocks 8 Columbia River Basalt, Yakima Basalt Subgroup 9 Ellensburg Formation 9 Gravels of the Ancestral Columbia River 13 Ringold Formation 15 Thorp Gravel 17 Gravel of Terrace Remnants 19 Tieton Andesite 23 Palouse Formation and Other Loess Deposits 23 Glacial Deposits 25 Catastrophic Flood Deposits 28 Background and previous work 30 Description and interpretation of flood deposits 35 Distinctive geomorphic features 38 Terraces and other features of undetermined origin 40 Post-Pleistocene Deposits 43 Landslide Deposits 44 Alluvium 45 Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Older Alluvial Fan Deposits 45 Colluvium 46 Sand Dunes 46 Mirna Mounds and Other Periglacial(?) Patterned Ground 47 Structural Geology 48 Southwest Quadrant 48 Toppenish Ridge 49 Ah tanum Ridge 52 Horse Heaven Hills 52 East Selah Fault 53 Northern Saddle Mountains and Smyrna Bench 54 Selah Butte Area 57 Miscellaneous Areas 58 Northwest Quadrant 58 Kittitas Valley 58 Beebe Terrace Disturbance 59 Winesap Lineament 60 Northeast Quadrant 60 Southeast Quadrant 61 Recommendations 62 Stratigraphy 62 Structure 63 Summary 64 References Cited 66 Appendix A - Tephrochronology and identification of collected datable materials 82 Appendix B - Description of field mapping units 88 Northeast Quadrant 89 Northwest Quadrant 90 Southwest Quadrant 91 Southeast Quadrant 92 ii ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. -

2017 COQUEREL Terroir Cabernet Sauvignon NAPA VALLEY

2017 COQUEREL terroir cabernet sauvignon NAPA VALLEY OVERVIEW Coquerel Family Wine Estates is located just beyond the town of Calistoga at the north end of the Napa Valley. The heart and soul of our winery is our estate vineyard, a gorgeous, oak-studded property that sits in the afternoon shadows of the Mayacamas Mountains. Since 2005, we have done extensive enhancement and replanting of the site to ensure world-class fruit from vintage to vintage. The combination of warm temperatures and deep, clay soils makes this ideal terroir for Sauvignon Blanc, our flagship variety. It also produces exceptional Verdelho, Tempranillo, Petite Sirah, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc. In 2015 we planted 4 acres of Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc on our estate. These were planted at a density of 3000 vines/acre using 3309 rootstock and 2 clones 269 and 4. In addition to our estate fruit, we source Cabernet and other noble grapes from a handful of premier growers throughout the Napa Valley. VINTAGE Vintage 2017 was our first crop of Cabernet Sauvignon off our estate vineyard. The year started with high rainfall after six years of drought in the Napa Valley. Due to the rain the vine canopy grew very quickly. As a result, all of our canopy management work had to be done earlier and quicker than in previous years. Overall, the season was relatively cool which gave a nice aroma to the fruit. We hand harvested our first crop on October 19th in the early morning. WINEMAKING The fruit was destemmed into a half ton bin and was cold soaked for 24 hours. -

Horse Heaven Hills, OR135-02

Year 2009 Inventory Unit Number/Name: Horse Heaven Hills, OR135-02 FORM I DOCUMENTATION OF BLM WILDERNESS INVENTORY FINDINGS ON RECORD: 1. Is there existing BLM wilderness inventory information on all or part of this area? No X (Go to Form 2) Yes (if more than one unit is within the area, list the names/numbers ofthose units.): a) Inventory Source:-------- b) Inventory Unit Name(s)INumber(s): _________ c) Map Name(s)INumber(s):_________ d) BLM District(s)/Field Office(s): ________ 2. BLM Inventory Findings on Record: Existing inventory information regarding wilderness characteristics (if more than one BLM inventory unit is associated with the area, list each unit and answer each question individually for each inventory unit): 1 Existing inventory information regarding wilderness characteristics : Inventory Source: ______________ Unit#/ Size Natural Outstanding Outstanding Supplemental Name (historic Condition? Solitude? Primitive & Values? acres) YIN YIN Unconfined YIN Recreation? YIN FORM2 Use additional pages as necessary DOCUMENTATION OF CURRENT WILDERNESS INVENTORY CONDITIONS a. Unit Number/Name: Horse Heaven Hills, OR135-02 (1) Is the unit of sufficient size? Yes ____ No_~x~-- The lands are approximately 6,557 acres of public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management, Spokane District, Border Field Office. The lands are located in Benton County, Washington and are approximately 1 mile south ofthe community of Benton City. The public lands are adjacent to several small parcels of lands owned by the State of Washington. The remainder of the boundary is private land parcels. There are no private lands in-holdings. The lands are broken in smaller subunits by the roads and the powerline. -

Periodically Spaced Anticlines of the Columbia Plateau

Geological Society of America Special Paper 239 1989 Periodically spaced anticlines of the Columbia Plateau Thomas R. Watters Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C. 20560 ABSTRACT Deformation of the continental flood-basalt in the westernmost portion of the Columbia Plateau has resulted in regularly spaced anticlinal ridges. The periodic nature of the anticlines is characterized by dividing the Yakima fold belt into three domains on the basis of spacings and orientations: (1) the northern domain, made up of the eastern segments of Umtanum Ridge, the Saddle Mountains, and the Frenchman Hills; (2) the central domain, made up of segments of Rattlesnake Ridge, the eastern segments of Horse Heaven Hills, Yakima Ridge, the western segments of Umtanum Ridge, Cleman Mountain, Bethel Ridge, and Manastash Ridge; and (3) the southern domain, made up of Gordon Ridge, the Columbia Hills, the western segment of Horse Heaven Hills, Toppenish Ridge, and Ahtanum Ridge. The northern, central, and southern domains have mean spacings of 19.6,11.6, and 27.6 km, respectively, with a total range of 4 to 36 km and a mean of 20.4 km (n = 203). The basalts are modeled as a multilayer of thin linear elastic plates with frictionless contacts, resting on a mechanically weak elastic substrate of finite thickness, that has buckled at a critical wavelength of folding. Free slip between layers is assumed, based on the presence of thin sedimentary interbeds in the Grande Ronde Basalt separating groups of flows with an average thickness of roughly 280 m. -

Appendix a Conceptual Geologic Model

Newberry Geothermal Energy Establishment of the Frontier Observatory for Research in Geothermal Energy (FORGE) at Newberry Volcano, Oregon Appendix A Conceptual Geologic Model April 27, 2016 Contents A.1 Summary ........................................................................................................................................... A.1 A.2 Geological and Geophysical Context of the Western Flank of Newberry Volcano ......................... A.2 A.2.1 Data Sources ...................................................................................................................... A.2 A.2.2 Geography .......................................................................................................................... A.3 A.2.3 Regional Setting ................................................................................................................. A.4 A.2.4 Regional Stress Orientation .............................................................................................. A.10 A.2.5 Faulting Expressions ........................................................................................................ A.11 A.2.6 Geomorphology ............................................................................................................... A.12 A.2.7 Regional Hydrology ......................................................................................................... A.20 A.2.8 Natural Seismicity ........................................................................................................... -

HFE Core Sell Sheet Pdf 1.832 MB

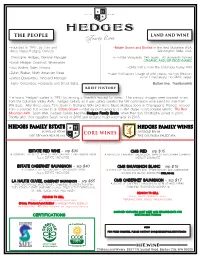

TRADE MARK THE PEOPLE LAND AND WINE amily state -Founded in 1987, by Tom and -Estate Grown and Bottled in the Red Mountain AVA, Anne-Marie Hedges, Owners Washington State, USA. -Christophe Hedges, General Manager -5 Estate Vineyards. 145 acres. All vineyards farmed ORGANIC AND/OR BIODYNAMIC -Sarah Hedges Goedhart, Winemaker -Boo Walker, Sales Director -CMS fruit is from the Columbia Valley AVA -Dylan Walker, North American Sales -Estate Vinification: Usage of wild yeasts, no/min filtration, -James Bukavinsky, Vineyard Manager sulfur if neccesary, no GMO, vegan -Kathy Cortembos, Hospitality and Direct Sales -Bottom line: Traditionalists BRIEF HISTORY The brand ‘Hedges’ started in 1987 by winning a Swedish request for wines. The primary vintages were sourced wines from the Columbia Valley AVA. Hedges Cellars, as it was called, created the first commerical wine blend for sale from WA State. After three years, Tom (born in Richland, WA) and Anne-Marie Hedges (born in Champagne, France), moved from a sourced fruit model to an Estate Grown model, by purchasing land in WA States’ most coveted terroir: The Red Mountain AVA. Soon after, Hedges Cellars became Hedges Family Estate, when their son Christophe joined in 2001. Shortly after, their daughter Sarah joined in 2006 and became head winemaker in 2015. HEDGES FAMILY ESTATE HEDGES FAMILY WINES SOURCED FROM SOURCED FROM THE RED MOUNTAIN AVA CORE WINES THE COLUMBIA VALLEY AVA ESTATE RED WINE - srp $30 CMS RED - srp $15 A DOMINATE BLEND OF MERLOT AND CABERNET SAUVIGNON FROM A BLEND OF CABERNET SAUVIGNON, MERLOT AND SYRAH CURRENT ALL 5 ESTATE VINEYARDS. MERLOT DOMINATE ESTATE CABERNET SAUVIGNON - srp $40 CMS SAUVIGNON BLANC - srp $15 A DOMINATE BLEND CABERNET SAUVIGNON FROM A BLEND OF SAUVIGNON BLANC, CHARDONNAY AND MARSANNE. -

Cabernet Sauvignon

2017 “ARTIST SERIES #26” CABERNET SAUVIGNON Our Woodward Canyon "Artist Series" began in 1992 with the intent to showcase the finest cabernet sauvignon in Washington State and has since become our flagship wine. The vineyards used in the "Artist Series" are among the oldest and most highly regarded in the state, typical vine age is around 25 years old. The label changes every year with work from a different Pacific Northwest artist. The 2017 vintage was a warm dry vintage with lower than normal yields resulting in concentrated fruit aromas and flavors. PAST ACCLAIM 92 Points, Robert Parker’s The Wine Advocate (v2016) 92 Points, Wine Spectator (v2016) 91+ Points, Vinous (v2016) 90 Points, Wine Enthusiast (v2016) Gold & Best of Class, 2019 Great Northwest Wines Invitational Wine Competition (v2016) 94 Points, Jeb Dunnuck (former WA critic for Wine Advocate) (v2015) 93 Points, JamesSuckling.com (v2015) 92 Points, Silver, Decanter World Wine Awards (v2015) VINEYARDS Champoux Vineyard (44%) Founded in 1972 and located in Alderdale Washington within the Horse Heaven Hills AVA. Woodward Canyon has been sourcing from Champoux since 1981. In 1996 Woodward Canyon and fellow Washington State producers Powers/Badger Mountain Winery, Quilceda Creek Winery and Andrew Will Winery became joint owners. Malaga gravelly fine sandy loam - glacial outwash; warden silt loam - loess over lacustrine deposits; Sagehill fine sandy loam - lacustrine deposits with a mantle of loess. Slope 3%, 650ft elevation. WINE DATA Woodward Canyon Estate Vineyard (25%) Established in 1976, Woodward Canyon is the western most vineyard in Walla Walla Valley AVA, roughly 15 miles west of Walla Walla, Washington. -

2016 Champoux Vineyard Red Wine

2016 Champoux Vineyard Red Wine We make the Champoux blend not just because we are such big fans of the vineyard, but because of the way that Merlot and Cabernet Franc shine from this site. This wine is the alter ego to Sorella. We almost always craft this wine with a nod towards a majority Cab Franc or Merlot in this case. This wine allows us to show the full range of Champoux Vineyard. The 2016 Vintage in Washington State started out quick during the spring, but in early June the weather returned to normal and thus lead to a start date of September 12th for picking. Harvest continued until October 25th with Cabernet Sauvignon from Two Blondes vineyard coming in. Right away we saw the high potential of the fruit and how this vintage would end up being another great vintage for us. Reviews: (97 Points)...One of the finest examples of this cuvée I’ve tasted is the 2016 Champoux Vineyard, which comes from one of the top terroirs in the state and is in the slightly cooler Horse Heaven Hills AVA. Young, full-bodied, and primordial, it has incredible potential but is going to need 4-5 years of bottle age. Thrilling notes of blueberries, cassis, lead pencil shavings, and bouquet garni all define the bouquet and it has remarkable purity and elegance. It picks up more floral and high-toned notes with time in the glass and is a brilliant bottle of wine that will keep for 2-3 decades. Jeb Dunnuck - Jebdunnuck.com (94+ Points)…Opens with a rich and ripe expression of dark, dusty fruit interlaced with supporting oak tones on the nose. -

Powers Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon Champoux Vineyard Horse Heaven Hills 2016

2016 Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon Champoux Vineyard TASTING NOTES Exquisite layered aromatics of blueberry, dark cherry, and cedar with hints of violets, vanilla and warm earth. This intriguing nose is followed by dense savory flavors of black currant, dark fruits, and cranberry with touches of cocoa, smoke and spice lingering on this complex palate. Firm, dusty, lush tannins are accented by hints of oak, acidity, and earthiness on the finish. As is typical of Champoux Vineyard, this is a very elegant yet powerful Cabernet Sauvignon that will cellar for many years. BLEND/VINEYARD INFO 94% Cabernet Sauvignon, 2% Cabernet Franc, 2% Merlot, & 2% Malbec 94% Champoux Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon, Horse Heaven Hills 2% Champoux Vineyard Cabernet Franc, Horse Heaven Hills 2% Champoux Vineyard Merlot, Horse Heaven Hills 2% Champoux Vineyard Malbec, Horse Heaven Hills WINEMAKER’S NOTES We have been fortunate to work with Champoux Vineyard fruit since 1992 and we believe it is the most intense and one of the most expressive vineyard sites in Washington State. The varietals were harvested from late Setember to late October with near perfect acididty and fruit flavors. We used the pump-under fermentation process with PDM yeast to enhance the nice richness you would expect from Champoux Vineyard. The wine was then aged for 32 months in 55% new French Oak barrels, 25% in 2nd fill along with the last 20% in neutral French Oak Barrels. TECHNICAL DATA Release Date: January 1, 2020 Alcohol: 14% Residual Sugar: Dry Acidity: 0.64 pH 3.84 Cases: 1190 . -

CSW Work Book 2021 Answer

Answer Key Key Answer Answer Key Certified Specialist of Wine Workbook To Accompany the 2021 CSW Study Guide Chapter 1: Wine Composition and Chemistry Exercise 1: Wine Components: Matching 1. Tartaric Acid 6. Glycerol 2. Water 7. Malic Acid 3. Legs 8. Lactic Acid 4. Citric Acid 9. Succinic Acid 5. Ethyl Alcohol 10. Acetic Acid Exercise 2: Wine Components: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. Tartaric Acid, Malic Acid, Citric Acid, and Succinic Acid 2. Citric Acid, Succinic Acid 3. Tartaric Acid 4. Malolactic Fermentation 5. TA (Total Acidity) 6. The combined chemical strength of all acids present 7. 2.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 8. 3.9 (considering the normal range of wine pH ranges from 2.9 – 3.9) 9. Glucose and Fructose 10. Dry Exercise 3: Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: Matching 1. Flavonols 7. Tannins 2. Vanillin 8. Esters 3. Resveratrol 9. Sediment 4. Ethyl Acetate 10. Sulfur 5. Acetaldehyde 11. Aldehydes 6. Anthocyanins 12. Carbon Dioxide Exercise 4: Phenolic Compounds and Other Components: True or False 1. False 7. True 2. True 8. False 3. True 9. False 4. True 10. True 5. False 11. False 6. True 12. False Chapter 1 Checkpoint Quiz 1. C 6. C 2. B 7. B 3. D 8. A 4. C 9. D 5. A 10. C Chapter 2: Wine Faults Exercise 1: Wine Faults: Matching 1. Bacteria 6. Bacteria 2. Yeast 7. Bacteria 3. Oxidation 8. Oxidation 4. Sulfur Compounds 9. Yeast 5. Mold 10. Bacteria Exercise 2: Wine Faults and Off-Odors: Fill in the Blank/Short Answer 1. -

Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I

Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I November 4 - 7, 2002 Richland, WA FINAL REPORT A Collaborative Workshop: United States Fish & Wildlife Service The Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/IUCN) Hanford Reach National Monument 1 Planning Workshop I, November 2002 A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group in collaboration with the United States Fish & Wildlife Service. CBSG. 2002. Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I. FINAL REPORT. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. 2 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I, November 2002 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I November 4-7, 2002 Richland, WA TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1. Executive Summary 1 A. Introduction and Workshop Process B. Draft Vision C. Draft Goals 2. Understanding the Past 11 A. Personal, Local and National Timelines B. Timeline Summary Reports 3. Focus on the Present 31 A. Prouds and Sorries 4. Exploring the Future 39 A. An Ideal Future for Hanford Reach National Monument B. Goals Appendix I: Plenary Notes 67 Appendix II: Participant Introduction questions 79 Appendix III: List of Participants 87 Appendix IV: Workshop Invitation and Invitation List 93 Appendix V: About CBSG 103 Hanford Reach National Monument 3 Planning Workshop I, November 2002 4 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I, November 2002 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I November 4-7, 2002 Richland, WA Section 1 Executive Summary Hanford Reach National Monument 5 Planning Workshop I, November 2002 6 Hanford Reach National Monument Planning Workshop I, November 2002 Executive Summary A. Introduction and Workshop Process Introduction to Comprehensive Conservation Planning This workshop is the first of three designed to contribute to the Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) of Hanford Reach National Monument.