Violent Deaths and Enforced Disappearances During the Counterinsurgency in Punjab, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Demons Within"

Demons Within the systematic practice of torture by inDian police a report by organization for minorities of inDia NOVEMBER 2011 Demons within: The Systematic Practice of Torture by Indian Police a report by Organization for Minorities of India researched and written by Bhajan Singh Bhinder & Patrick J. Nevers www.ofmi.org Published 2011 by Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc. Copyright © 2011 by Organization for Minorities of India. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise or conveyed via the internet or a web site without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Inquiries should be addressed to: Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc PO Box 392 Lathrop, CA 95330 United States of America www.sovstar.com ISBN 978-0-9814992-6-0; 0-9814992-6-0 Contents ~ Introduction: India’s Climate of Impunity 1 1. Why Indian Citizens Fear the Police 5 2. 1975-2010: Origins of Police Torture 13 3. Methodology of Police Torture 19 4. For Fun and Profit: Torturing Known Innocents 29 Conclusion: Delhi Incentivizes Atrocities 37 Rank Structure of Indian Police 43 Map of Custodial Deaths by State, 2008-2011 45 Glossary 47 Citations 51 Organization for Minorities of India • 1 Introduction: India’s Climate of Impunity Impunity for police On October 20, 2011, in a statement celebrating the Hindu festival of Diwali, the Vatican pled for Indians from Hindu and Christian communities to work together in promoting religious freedom. -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala (Established under Punjab Act No. 35 of 1961) Editor Dr. Shivani Thakar Asst. Professor (English) Department of Distance Education, Punjabi University, Patiala Laser Type Setting : Kakkar Computer, N.K. Road, Patiala Published by Dr. Manjit Singh Nijjar, Registrar, Punjabi University, Patiala and Printed at Kakkar Computer, Patiala :{Bhtof;Nh X[Bh nk;k wjbk ñ Ò uT[gd/ Ò ftfdnk thukoh sK goT[gekoh Ò iK gzu ok;h sK shoE tk;h Ò ñ Ò x[zxo{ tki? i/ wB[ bkr? Ò sT[ iw[ ejk eo/ w' f;T[ nkr? Ò ñ Ò ojkT[.. nk; fBok;h sT[ ;zfBnk;h Ò iK is[ i'rh sK ekfJnk G'rh Ò ò Ò dfJnk fdrzpo[ d/j phukoh Ò nkfg wo? ntok Bj wkoh Ò ó Ò J/e[ s{ j'fo t/; pj[s/o/.. BkBe[ ikD? u'i B s/o/ Ò ô Ò òõ Ò (;qh r[o{ rqzE ;kfjp, gzBk óôù) English Translation of University Dhuni True learning induces in the mind service of mankind. One subduing the five passions has truly taken abode at holy bathing-spots (1) The mind attuned to the infinite is the true singing of ankle-bells in ritual dances. With this how dare Yama intimidate me in the hereafter ? (Pause 1) One renouncing desire is the true Sanayasi. From continence comes true joy of living in the body (2) One contemplating to subdue the flesh is the truly Compassionate Jain ascetic. Such a one subduing the self, forbears harming others. (3) Thou Lord, art one and Sole. -

Reading Modern Punjabi Poetry: from Bhai Vir Singh to Surjit Patar

185 Tejwant S. Gill: Modern Punjabi Poetry Reading Modern Punjabi Poetry: From Bhai Vir Singh to Surjit Patar Tejwant Singh Gill Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar ________________________________________________ The paper evaluates the specificity of modern Punjabi poetry, along with its varied and multi-faceted readings by literary historians and critics. In terms of theme, form, style and technique, modern Punjabi poetry came upon the scene with the start of the twentieth century. Readings colored by historical sense, ideological concern and awareness of tradition have led to various types of reactions and interpretations. ________________________________________________________________ Our literary historians and critics generally agree that modern Punjabi poetry began with the advent of the twentieth century. The academic differences which they have do not come in the way of this common agreement. In contrast, earlier critics and historians, Mohan Singh Dewana the most academic of them all, take the modern in the sense of the new only. Such a criterion rests upon a passage of time that ushers in a new way of living. How this change then enters into poetic composition through theme, motif, technique, form, and style is not the concern of critics and historians who profess such a linear view of the modern. Mohan Singh Dewana, who was the first scholar to write the history of Punjabi literature, did not initially believe that something innovative came into being at the turn of the past century. If there was any change, it was not for the better. In his path-breaking History of Punjabi Literature (1932), he bemoaned that a sharp decline had taken place in Punjabi literature. -

The Sikh Prayer)

Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to: Professor Emeritus Dr. Darshan Singh and Prof Parkash Kaur (Chandigarh), S. Gurvinder Singh Shampura (member S.G.P.C.), Mrs Panninder Kaur Sandhu (nee Pammy Sidhu), Dr Gurnam Singh (p.U. Patiala), S. Bhag Singh Ankhi (Chief Khalsa Diwan, Amritsar), Dr. Gurbachan Singh Bachan, Jathedar Principal Dalbir Singh Sattowal (Ghuman), S. Dilbir Singh and S. Awtar Singh (Sikh Forum, Kolkata), S. Ravinder Singh Khalsa Mohali, Jathedar Jasbinder Singh Dubai (Bhai Lalo Foundation), S. Hardarshan Singh Mejie (H.S.Mejie), S. Jaswant Singh Mann (Former President AISSF), S. Gurinderpal Singh Dhanaula (Miri-Piri Da! & Amritsar Akali Dal), S. Satnam Singh Paonta Sahib and Sarbjit Singh Ghuman (Dal Khalsa), S. Amllljit Singh Dhawan, Dr Kulwinder Singh Bajwa (p.U. Patiala), Khoji Kafir (Canada), Jathedar Amllljit Singh Chandi (Uttrancbal), Jathedar Kamaljit Singh Kundal (Sikh missionary), Jathedar Pritam Singh Matwani (Sikh missionary), Dr Amllljit Kaur Ibben Kalan, Ms Jagmohan Kaur Bassi Pathanan, Ms Gurdeep Kaur Deepi, Ms. Sarbjit Kaur. S. Surjeet Singh Chhadauri (Belgium), S Kulwinder Singh (Spain), S, Nachhatar Singh Bains (Norway), S Bhupinder Singh (Holland), S. Jageer Singh Hamdard (Birmingham), Mrs Balwinder Kaur Chahal (Sourball), S. Gurinder Singh Sacha, S.Arvinder Singh Khalsa and S. Inder Singh Jammu Mayor (ali from south-east London), S.Tejinder Singh Hounslow, S Ravinder Singh Kundra (BBC), S Jameet Singh, S Jawinder Singh, Satchit Singh, Jasbir Singh Ikkolaha and Mohinder Singh (all from Bristol), Pritam Singh 'Lala' Hounslow (all from England). Dr Awatar Singh Sekhon, S. Joginder Singh (Winnipeg, Canada), S. Balkaran Singh, S. Raghbir Singh Samagh, S. Manjit Singh Mangat, S. -

Census of India 2011

Census of India 2011 PUNJAB SERIES-04 PART XII-B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK TARN TARAN VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS PUNJAB CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 PUNJAB SERIES-04 PART XII - B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK TARN TARAN VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations PUNJAB MOTIF GURU ANGAD DEV GURUDWARA Khadur Sahib is the sacred village where the second Guru Angad Dev Ji lived for 13 years, spreading the universal message of Guru Nanak. Here he introduced Gurumukhi Lipi, wrote the first Gurumukhi Primer, established the first Sikh school and prepared the first Gutka of Guru Nanak Sahib’s Bani. It is the place where the first Mal Akhara, for wrestling, was established and where regular campaigns against intoxicants and social evils were started by Guru Angad. The Stately Gurudwara here is known as The Guru Angad Dev Gurudwara. Contents Pages 1 Foreword 1 2 Preface 3 3 Acknowledgement 4 4 History and Scope of the District Census Handbook 5 5 Brief History of the District 7 6 Administrative Setup 8 7 District Highlights - 2011 Census 11 8 Important Statistics 12 9 Section - I Primary Census Abstract (PCA) (i) Brief note on Primary Census Abstract 16 (ii) District Primary Census Abstract 21 Appendix to District Primary Census Abstract Total, Scheduled Castes and (iii) 29 Scheduled Tribes Population - Urban Block wise (iv) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes (SC) 37 (v) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Tribes (ST) 45 (vi) Rural PCA-C.D. blocks wise Village Primary Census Abstract 47 (vii) Urban PCA-Town wise Primary Census Abstract 133 Tables based on Households Amenities and Assets (Rural 10 Section –II /Urban) at District and Sub-District level. -

Saffron Cloud

WAY OF THE SAFFRON CLOUD MYSTERY OF THE NAM-JAP TRANSCENDENTAL MEDITATION THE SIKH WAY A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO CONCENTRATION Dr. KULWANT SINGH PUBLISHED AS A SPECIAL EDITION OF GURBANI ISS JAGG MEH CHANAN, TO HONOR 300TH BIRTHDAY OF THE KHALSA, IN 1999. WAY OF THE SAFFRON CLOUD Electronic Version, for Gurbani-CD, authored by Dr. Kulbir Singh Thind, 3724 Hascienda Street, San Mateo, California 94403, USA. The number of this Gurbani- CD, dedicated to the sevice of the Panth, is expected to reach 25,000 by the 300th birthday of the Khalsa, on Baisakhi day of 1999. saffron.doc, MS Window 95, MS Word 97. 18th July 1998, Saturday, First Birthday of Sartaj Singh Khokhar. Way of the Saffron Cloud. This book reveals in detail the mystery of the Name of God. It is a spiritual treatise for the uplift of the humanity and is the practical help-book (Guide) to achieve concentration on the Naam-Jaap (Recitation of His Name) with particular stress on the Sikh-Way of doing it. It will be easy to understand if labeled "Transcendental Meditation the Sikh -Way," though meditation is an entirely different procedure. Main purpose of this book is to train the aspirant from any faith, to acquire the ability to apply his -her own mind independently, to devise the personalized techniques to focus it on the Lord. Information about the Book - Rights of this Book. All rights are reserved by the author Dr. Kulwant Singh Khokhar, 12502 Nightingale Drive, Chester, Virginia 23836, USA. Phone – mostly (804)530-0160, and sometimes (804)530-5117. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Amritsar, Part XII- a & B

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES-20 PUNJAB DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII - A & B VILLAGE &TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE &TOWNWIS"E PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DISTRICT AMRITSAR Director of Census Operations punjab PUNJAB 'DISTRICT AMRITSAR / () A ·M-'port of t.h.d Patti foil. in tahsil Torn Taron' C.O.BLOCKS A AJNALA B CHOGAWAN C VERKA BOUNDARY, INTERNATIONAl .. .. .. " " .. .. " .. ..' .... _. _. - o MAJITHA DISTRICT ...... " ...................... _._._ TAHSIL ............... "" ............. _._._ E JANDtALA • C.D.BLOCIL F TARSIKKA .... """ .. " ~~-@;@ HEADQUARTERS: DISTRICT; TAHSIL ... .. " " " " .. _:.:;NH",I,--_ G RAYYA NATIONAL HIGHWAY SH25 STATE HIGHWAY H KHADUR SAHIB IMPORTANT METALLI!:D ROAD .. ......... ,,--- I CHOHLA SAHIB RAILWAY LINE WITH STATION, BROAD GAUGE ...... ' .... " ; J NAUSHEHRA PANNUAN RIVER AND STREAM .... " .............. " .. " ...... ~ VILLAGE HAV1NG !!ODD AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME . .. A19OII. K TARN TARAN ~:gA~1 A~~. ~~T~ :.o~ULATION SIZE CLASS .I ~"~:I~~~ ... ...... L GANDIWIND POST AND TELEGRAPH OFFICE .. .. .. .. PTO M BHIKHIWIND DEGREE COLLEGE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION " .. .. .. .. ~[IJ VALTOHA REST HOUSE .... " .. , .. .. .... _........ " .... RH N' ' 0 PATTI , 1. All boundorl •• oro updalH upl" 101 Oece_. le8e. DISTRICT HEADQUARTERS IS ALSO TAHSIL HEADQUARTERS ~~~==~~~~ ______~ ________--------J s-d UI)OII Sllvrt,of india map wlt~ tile ,ponniaolon of tho Sunoo,or General of India. TM cOlIne of IN RAVI/SATLUJ RIVER ....... to conllnual chongt owing 10 "'Ifling of Iho river bed. CENSUS OF INOIA-1991 A-CENTHAL -

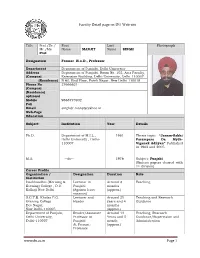

Faculty Detail Page on DU Web-Site

Faculty Detail page on DU Web-site Title Prof./Dr./ First Last Photograph Mr./Ms Name MANJIT Name SINGH Prof. Designation Former H.o.D., Professor Department Department of Punjabi, Delhi University Address Department of Punjabi, Room No. 102, Arts Faculty, (Campus) Extension Building, Delhi University, Delhi-110007 (Residence) B-60, IInd Floor, Fateh Nagar, New Delhi-110018 Phone No 27666621 (Campus) (Residence) optional Mobile 9868773902 Fax Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. Department of M.I.L., 1981 Thesis topic: “Janam-Sakhi Delhi University , Delhi- Parampara Da Myth- 110007 Viganak Adhyan” Published in 1982 and 2005. M.A. --do-- 1976 Subject: Punjabi (Sixteen papers cleared with 1st division) Career Profile Organization / Designation Duration Role Institution Deshbandhu (Morning & Lecturer in Around 2 Teaching Evening) College , D.U. Punjabi months Kalkaji New Delhi (Against leave (approx.) vacancy) S.G.T.B. Khalsa P.G. Lecturer and Around 25 Teaching and Research Evening College Reader years and 4 Guidance Dev Nagar, months New Delhi-110005 (approx.) Department of Punjabi, Reader/Associate Around 13 Teaching, Research Delhi University, Professor in Years and 5 Guidance/Supervision and Delhi-110007 Punjabi month Administration At Present: (approx.) Professor www.du.ac.in Page 1 Research Interests / Specialization Mythology & The Science of Myth and Gurmat Poetry Folkloristics, Cross-disciplinary Semiotics Western Poetics and Culturology, Medieval and Modern Punjabi Literature. Research Supervision A. Supervision of awarded Doctoral Theses ______________________________________________________________________________ S.No. Title of the Thesis Year of Present Name of the Scholar Submission Position 1 “San 1850 ton 1900 tak Di 1995 Approved Ms. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E2580 HON

E2580 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks December 13, 2007 shape of Texas. He has also become popular tion’s schools. These incidents have occurred Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit. Mr. as a cornerstone for community service. all over the country. While some thought Col- Wheeler’s career is marked by numerous hos- After living in the U.S. for a while, he be- umbine was an aberration, it has become pital administration roles and a dedication to came frustrated with the fact that voter turnout clear that this is a serious and growing prob- our men and women who have served in the in American elections was so low. Because of lem in our country that must be addressed. Armed Forces. this, he hosted a voter registration drive at his It is important to point out that in the late Mr. Wheeler was born in Detroit and moved hotel. To encourage residents to participate, 80’s and early 90’s when overall crime was to Canton, Ohio, when he was a teenager. He he offered a free breakfast for registering. going down, youth and young adult arrest received a BS in business administration from Philippe is extremely active as this year’s rates were increasing. the University of Dayton and an MA in hospital president of the Humble Intercontinental Ro- We must ask ourselves why. What makes a administration from Xavier University in Cin- tary and has been named Rotarian of the Year 14-year old feel so disengaged from society cinnati. Mr. Wheeler began his career as a on occasion. -

Satwant Kaur Bhai Vir Singh

Satwant !(aUll BHAI VIR SINGH Translator Rima!· Kaur """"'~"""'Q~ ....#•" . Bhai Vir Singh Sahitya Sadan Bhai Vir Singh Marg New Delhi-110 001 Page 1 www.sikhbookclub.com Satwant Kaur Bhai Vir Singh Translated by BimalKaur © Bhai Vir Singh Sahitya Sadan, New Delhi New Edition: 2008 Publisher: Bhai Vir Singh Sahitya Sadan BhaiVir Singh Marg New Delhi-11 a 001 Printed at: IVY Prints 29216, Joor Bagh Kotla Mubarakpur New Delhi-11 0003 Price; 60/- Page 2 www.sikhbookclub.com , Foreword The Sikh faith founded by Guru Nanak (1469-1539) has existed barely for five centuries; but this relatively short period has been packed with most colourful and inspiring history. Sikhism, as determined by the number of its adherents, is one of the ten great religions of the world. Its principles of monotheism, egalitarianism and proactive martyrdom for freedom of faith represent major evolutionary steps in the development of religious philosophies. Arnold Toynbee, the great world historian, observed: "Mankind's religious future may be obscure; yet one thing can be foreseen. The living higher religions are going to influence each other more than ever before in the days ofincreasing communication between all parts of the world and all branches of the human race. In this coming religious debate, the Sikh religion, and its scripture, the Adi Granth, will have something of special value to say to the rest of the world." Notwithstanding such glowing appreciation oftheir role, information about the Sikhs'contribution to world culture has been very scantily propagated. Bhai Vir Singh, the modem doyen ofSikh world of letters, took upon himself to provide valuable historical accounts of the Sikh way of life. -

Sr. No. Division Centre Name Centre Code Type Tehsil Block Near Land

Sr. No. Division Centre Name Centre Code Type Tehsil Block Near Land Mark 1 Bhikhiwind SUB TEHSIL, BHIKHIWIND PB-050-00259-U004 2 Patti Bhikhiwind Near Sub-Tehsil, Bhikhiwind 2 Bhikhiwind Near Civil Hospital, Khalra Mandi PB-050-00260-R002 3 Patti Bhikhiwind Near Civil Hospital, Khalra Mandi Near Grain Market, Main Road , Algo 3 Bhikhiwind Near Main Road, Algon Kothi PB-050-00259-R039 3 Patti Bhikhiwind Kothi 4 Bhikhiwind Near Panchayat Ghar, Sursingh PB-050-00260-R006 3 Patti Bhikhiwind Opp CHC , Sursingh 5 Khadoor Sahib Tehsil office, Khadur Sahib PB-050-00259-U005 2 Khadoor Sahib Khadoor Sahib Tehsil office, Khadur Sahib 6 Khadoor Sahib Near Community Center, Fatehbad PB-050-00261-R004 3 Khadoor Sahib Khadoor Sahib Near Community Center, Fatehbad 7 Khadoor Sahib Near Panchayat Ghar, Jalalabad PB-050-00261-R015 3 Khadoor Sahib Khadoor Sahib Near Panchayat Ghar, Jalalabad 8 Khadoor Sahib Near Sub Tehsil, Goindwal Sahib PB-050-00261-R006 3 Khadoor Sahib Khadoor Sahib Near Sub Tehsil, Goindwal Sahib 9 Patti NEAR SUB TEHSIL, KHEMKARAN PB-050-00259-U003 2 Patti Valtoha NEAR SUB TEHSIL, KHEMKARAN VETERINARY HOSPITAL, LAHORE ROAD, NEAR VETERINARY HOSPITAL, LAHORE 10 Patti PB-050-00259-U002 2 Patti Patti PATTI ROAD, PATTI 11 Patti Near Community Center, Sabhra PB-050-00260-R032 3 Patti Patti Near Community Center, Sabhra 12 Patti Near Community Center, Mehmoodpura PB-050-00260-R015 3 Patti Valtoha Near Community Center, Mehmoodpura 13 Patti Near Sub Tehsil, Harike PB-050-00260-R035 3 Patti Patti Near Sub Tehsil, Harike 14 Patti On Main Road, Ghariala PB-050-00260-R022 3 Patti Valtoha On Main Road, Ghariala DC OFFICE COMPLEX , VPO PIDDI, TARN 15 Tarn Taran DC OFFICE COMPLEX PB-050-00259-U001 1 Tarn Taran Tarn Taran TARAN 16 Tarn Taran Tehsil office, Tarn Taran PB-050-00259-U006 2 Tarn Taran Tarn Taran OPP. -

GROUND WATER RESOURCES of PUNJAB STATE (As on 31 March

GROUND WATER RESOURCES OF PUNJAB STATE (As on 31st March, 2017) CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD WATER RESOURCES & ENVIRONMENT NORTH WESTERN REGION DIRECTORATE, PUNJAB CHANDIGARH WATER RESOURCES DEPARTMENT MOHALI OCTOBER, 2018 i GROUND WATER RESOURCES OF PUNJAB STATE (As on 31st March, 2017) Prepared by WATER RESOURCES & ENVIRONMENT DIRECTORATE, WATER RESOURCES DEPARTMENT, PUNJAB, MOHALI and CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD NORTH WESTERN REGION CHANDIGARH OCTOBER, 2018 ii FOREWORD One of the prime requisites for self-reliance and development of any state is the optimal development of its Water Resources. Ground Water being easily accessible, less expensive, more dependable and comparatively low in pollution has its merits. In order to develop this precious natural resource in a judicious and equitable manner, it is essential to have knowledge of its availability, present withdrawal and future scope of its development. The present ground water assessment report has been computed by the officers & officials of the Water Resources & Environment Directorate, Water Resources Department Punjab, along with Department of Agriculture & Farmer’s Welfare and Punjab Water Resources Management and Development Corporation Limited on the basis of latest guidelines by the Ground Water Resource Estimation Committee (GEC 2015), Government of India,. The report gives details on total annual recharge to ground water, its present draft and scope for future block-wise development. The present ground water development in the state is 165% as on March 2017. Out of 138 blocks of the state taken for study, 109 blocks are “Over-exploited”, 2 blocks are “Critical”, 5 blocks are “Semi-critical” and 22 blocks are in “Safe” category. There is an urgent need to recharge ground water in the over-exploited blocks and develop available shallow ground water in the safe blocks to avoid water logging in the foreseeable future.