THE EARLY HISTORY of GOTHIC SPIRES Chapter 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Truss Terminology

TRUSS TERMINOLOGY BEARING WIDTH The width dimension of the member OVERHANG The extension of the top chord beyond the providing support for the truss (usually 3 1/2” or 5 1/2”). heel joint. Bearing must occur at a truss joint location. PANEL The chord segment between two adjacent joints. CANTILEVER That structural portion of a truss which extends PANEL POINT The point of intersection of a chord with the beyond the support. The cantilever dimension is measured web or webs. from the outside face of the support to the heel joint. Note that the cantilever is different from the overhang. PEAK Highest point on a truss where the sloped top chords meet. CAMBER An upward vertical displacement built into a truss bottom chord to compensate for defl ection due to dead load. PLATE Either horizontal 2x member at the top of a stud wall offering bearing for trusses or a shortened form of connector CHORDS The outer members of a truss that defi ne the plate, depending on usage of the word. envelope or shape. PLUMB CUT Top chord cut to provide for vertical (plumb) TOP CHORD An inclined or horizontal member that establishes installation of fascia. the upper edge of a truss. This member is subjected to compressive and bending stresses. SCARF CUT For pitched trusses only – the sloping cut of upper portion of the bottom chord at the heel joint. BOTTOM CHORD The horizontal (and inclined, ie. scissor trusses) member defi ning the lower edge of a truss, carrying SLOPE (PITCH) The units of horizontal run, in one unit of ceiling loads where applicable. -

Download This Article

Common Threads Structural Issues in Historic Buildings By Craig M. Bennett, Jr., P.E. Charleston, South Carolina is blessed with historic structures. Eighteenth and nineteenth century houses, churches and civic buildings adorn every block. The city has ® interesting challenges for the structural engineer… the east coast’s largest earthquake, hurricanes, city-wide fires and poor soils have put buildings and their designers to the test. Because the primary structural materials found here, soil, masonry, timber and iron, are the same as those used everywhere over the last three centuries, struc- tural issues common to buildings in Charleston are found in historic buildings all over the nation. Buildings move due to consolidation of soils; masonry cracks; lime leaches out of mortar; timber creeps under stress and rots when faced with water intrusion and iron corrodes. The only threat not severe here is a regular freeze- thaw cycle. Copyright A look at a few of these historic structuresCopyright© and a comparison of their behavior with that of other buildings found around the southeast will show the similarities in the Pompion Hill Chapel, Huger, SC - 1763 issues the preservation engineer faces. Replacement of the failed trusses in 1751 - St. Michael’s had settled several inches and had been kind would have been appropriate from Episcopal Church, severely fractured. After 1989’s Hurri- a preservation standpoint, but exact cane Hugo, we had had to straighten the replacement timber members would Charleston, South Carolina top 50 feet, the timber spire. We were have, in time, failed under load like the Construction on the brick masonry for also aware that we had potential lateral original. -

Pevsner's Architectural Glossary

Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 1 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 2 Nikolaus and Lola Pevsner, Hampton Court, in the gardens by Wren's east front, probably c. Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 3 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Yale University Press New Haven and London Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 4 Temple Street, New Haven Bedford Square, London www.pevsner.co.uk www.lookingatbuildings.org.uk www.yalebooks.co.uk www.yalebooks.com for Published by Yale University Press Copyright © Yale University, Printed by T.J. International, Padstow Set in Monotype Plantin All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 5 CONTENTS GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 6 FOREWORD The first volumes of Nikolaus Pevsner’s Buildings of England series appeared in .The intention was to make available, county by county, a comprehensive guide to the notable architecture of every period from prehistory to the present day. Building types, details and other features that would not necessarily be familiar to the general reader were explained in a compact glossary, which in the first editions extended to some terms. -

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021 SAMPLE OF PROGRAM* Day 1: Friday, May 21, 2021 Arrival in Paris on your own Group Welcome Dinner in a restaurant Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 2: Saturday May 22, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris. Guided visit of the church of St Pierre de Montmartre, one of the oldest extant churches in Paris, and the Sacré Coeur Basilica with its mosaic of Christ in Glory. Lunch on your own in historic Montmartre After lunch, meet your tour bus for a guided visit of the St Denis Basilica to learn about the birth of Gothic architecture Return to the hotel at the end of the day. Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 3: Sunday, May 23, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and your 2 guides in front of your hotel for a day trip to Chartres. Guided tour of Notre Dame de Chartres Cathedral, a unique example of early gothic architecture, th and its 13 century Labyrinth Group Lunch in a restaurant Free time to explore the town of Chartres Return to Paris with your tour bus at the end of the day Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 4: Monday, May 24, 2021 Meet your 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris (transport pass provided) Guided visit of Notre Dame Cathedral (the exterior), an iconic masterpiece of Gothic architecture, ravaged by fire in April 2019. -

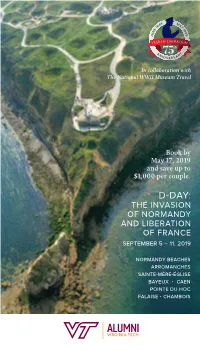

2019 Flagship Vatech Sept5.Indd

In collaboration with The National WWII Museum Travel Book by May 17, 2019 and save up to $1,000 per couple. D-DAY: THE INVASION OF NORMANDY AND LIBERATION OF FRANCE SEPTEMBER 5 – 11, 2019 NORMANDY BEACHES ARROMANCHES SAINTE-MÈRE-ÉGLISE BAYEUX • CAEN POINTE DU HOC FALAISE • CHAMBOIS NORMANDY CHANGES YOU FOREVER Dear Alumni and Friends, Nothing can match learning about the Normandy landings as you visit the ery places where these events unfolded and hear the stories of those who fought there. The story of D-Day and the Allied invasion of Normandy have been at the heart of The National WWII Museum’s mission since they opened their doors as The National D-Day Museum on June 6, 2000, the 56th Anniversary of D-Day. Since then, the Museum in New Orleans has expanded to cover the entire American experience in World War II. The foundation of this institution started with the telling of the American experience on D-Day, and the Normandy travel program is still held in special regard – and is considered to be the very best battlefield tour on the market. Drawing on the historical expertise and extensive archival collection, the Museum’s D-Day tour takes visitors back to June 6, 1944, through a memorable journey from Pegasus Bridge and Sainte-Mère-Église to Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc. Along the way, you’ll learn the timeless stories of those who sacrificed everything to pull-off the largest amphibious attack in history, and ultimately secured the freedom we enjoy today. Led by local battlefield guides who are experts in the field, this Normandy travel program offers an exclusive experience that incorporates pieces from the Museum’s oral history and artifact collections into presentations that truly bring history to life. -

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

Put the Pedal to the Metal CONTINUING EDUCATION

2 EDUCATIONAL-ADVERTISEMENT Photo courtesy of Alucobond/Connor Group/Daniel Lunghi Photography CONTINUING EDUCATION CONTINUING Put the Pedal to the Metal CONTINUING EDUCATION Metal roofing and wall systems’ longevity, recyclability, 1 AIA LU/HSW and compatibility with retrofits and rooftop solar Learning Objectives After reading this article, you should be able to: technology present an impressive sustainable scorecard 1. Define the primary advantages that metal and metal roofs offer in delivering a long- Sponsored by Metal Construction Association lasting, energy-efficient building enclosure. 2. Identify the predominant aspects of metal one of the three little pigs built a account of their sustainable attributes. “Many roofing systems that make them highly house out of metal, but it would have metal products in the construction industry compatible with rooftop solar technologies N been a good way to keep away the big, are manufactured with recycled materials,” he and life-cycle benefits. bad wolf. explains. Notably, “it’s an excellent reuse or 3. List key integrated building systems and Sturdy, strong, and sustainable metal walls repurposing of materials that might previously strategies for maximizing energy and and roof panels are known for their durable have ended up in a landfill.” performance savings with metal roofing and green features. Metal is almost unbeatable One-hundred percent recyclable, metal retrofits. among building materials for its recyclable walls and roofs can also be manufactured 4. Discuss case studies illustrating the sustainability of metal roofing and wall properties, and metal walls and roofs contrib- with 40 percent recycled steel. This figure is systems. ute to reduced energy consumption, as their especially impressive in light of the estimated well-known cool roofing properties reflect heat 11 million tons of asphalt shingles that end To receive AIA credit, you are required to read energy and absorb less heat, keeping buildings up in landfills. -

Geometric Proportioning Strategies in Gothic Architectural Design Robert Bork*

$UFKLWHFWXUDO Bork, R 2014 Dynamic Unfolding and the Conventions of Procedure: Geometric +LVWRULHV Proportioning Strategies in Gothic Architectural Design. Architectural Histories, 2(1): 14, pp. 1-20, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/ah.bq RESEARCH ARTICLE Dynamic Unfolding and the Conventions of Procedure: Geometric Proportioning Strategies in Gothic Architectural Design Robert Bork* This essay explores the proportioning strategies used by Gothic architects. It argues that Gothic design practice involved conventions of procedure, governing the dynamic unfolding of successive geometrical steps. Because this procedure proves difficult to capture in words, and because it produces forms with a qualitatively different kind of architectural order than the more familiar conventions of classical design, which govern the proportions of the final building rather than the logic of the steps used in creating it, Gothic design practice has been widely misunderstood since the Renaissance. Although some authors in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries attempted to sympathetically explain Gothic geometry, much of this work has been dismissed as unreliable, especially in the influential work of Konrad Hecht. This essay seeks to put the study of Gothic proportion onto a new and firmer foundation, by using computer-aided design software to analyze the geometry of carefully measured buildings and original design drawings. Examples under consideration include the parish church towers of Ulm and Freiburg, and the cross sections of the cathedrals of Reims, Prague, and Clermont-Ferrand, and of the Cistercian church at Altenberg. Introduction of historic monuments to be studied with new rigor. It is Discussion of proportion has a curiously vexed status in finally becoming possible, therefore, to speak with reason- the literature on Gothic architecture. -

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

2018 | 2 Éric Bournazel, Mutations

2018 | 2 Éric Bournazel, Mutations. Recueil d’articles d’histoire du Mittelalter – Moyen Âge (500– droit, Paris (Éditions Panthéon-Assas) 2017, 530 p., 1 ill., 1500) ISBN 979-10-90429-96-3, EUR 35,00. DOI: 10.11588/frrec.2018.2.48295 rezensiert von | compte rendu rédigé par Patrick Demouy, Reims Seite | page 1 Le titre de ce recueil fait référence au grand livre qu’Éric Bournazel a publié avec Jean-Pierre Poly en 1980, »La mutation féodale (Xe–XIIe siècles)«. Traduit en espagnol, italien et anglais, il est devenu un classique réédité et a alimenté les débats historiographiques. Ceux-ci ne sont pas relancés. Éric Bournazel, qui s’est affirmé comme un spécialiste des premiers Capétiens et de la féodalité, nous offre un florilège d’histoire institutionnelle et juridique, sans s’interdire des réflexions anthropologiques et des excursions loin du domaine qui est a priori le sien, signe d’une curiosité toujours en éveil. On en jugera par les titres des cinq sections regroupant 29 articles: »Les cercles du pouvoir«; »Jus et Ars«; »Imaginaires«,»idées«, idéologies«; »Le gouvernement des femmes«; »Échappées sportives«. Le fil conducteur de la première partie est le processus de récupération de la féodalité par la royauté. Au cours du XIIe siècle se développe une royauté suzeraine qui domine les hommes parce qu’elle domine les fiefs. D’où le concept de mouvance, ce rapport immuable entre les terres qui entraîne la chaîne des hommages. Suger utilise le terme de fief pour définir les principautés et les intégrer dans une pyramide au sommet de laquelle se trouve le roi, ou plutôt la Couronne, une abstraction distincte de la personne physique et mortelle du souverain, un concept qui a pris forme pendant l’absence de Louis VII, parti à la croisade (1147–1149). -

Hie Est Wadard: Vassal of Odo of Bayeux Or Miles and Frater of St Augustine's, Canterbury?'

Reading Medieval Studies XL (20 14) Hie est Wadard: Vassal of Odo of Bayeux or Miles and Frater of St Augustine's, Canterbury?' Stephen D. White Emory University On the Bayeux Embroidery, the miles identified as Wadard by the accompanying inscription (W 46: Hie est Wadarcf) has long been known as a 'vassal' of William l's uterine brother, Odo of Bayeux (or de Conteville), who was Bishop of Bayeux from 104911050 until his death in 1097; earl of Kent from e. 1067 until hi s exile in 1088; and prior to his imprisonment in 1082, the greatest and most powerful landholder after the king.' Wadard appears just after Duke William's invading army has landed at Pevensey (W 43) and four of his milites have hurried to Hastings to seize food (W 44-5: Et hie milites festinaverunt hestinga lit eibum raperentur).' On horseback, clad in a hauberk and armed with a shield and spear, Wadard supervises as animals are brought to be slaughtered by an axe-wielding figure (W 45) and then cooked (W 46). Writing in 1821, Charles Stoddard was unable to identify Wadard, because written accounts of the conquest never mention him .4 Nevertheless, he cited his image, along with those of two other men called Turold (W 11) and Vital (W 55), as evidence that the hanging must have dated from 'the time of the Conquest', when its designer and audience could still have known of men as obscure as Wadard and the other two obviously were.' In 1833, Wadard was first identified authoritatively as Odo's 'sub-tenant' by Henry Ellis in A General introduction to Domesday Book, though as far back as 1821 Thomas Amyot had I am deeply indebted to Kate Gilbert fo r her work in researching and editing this article and to Elizabeth Carson Pastan for her helpful suggestions and criticisms. -

Jan Lewandoski Restoration and Traditional Building 92 Old Pasture Rd

Jan Lewandoski Restoration and Traditional Building 92 Old Pasture Rd. Greensboro Bend , Vermont 05842 802-533-2561; 802-274-4318 [email protected] May 7, 2020 The Granville Town Hall, Granville Vermont A Preservation Trust of Vermont Technical Assistance Survey The Granville Town Hall is a tall 2-story, white, clapboarded structure located on the west side of Rt. 100 at the center of Town. It was first built as a church in 1871. It is currently attached to the Town Offices, which are located in the Town’s 1857 schoolhouse. The Town Hall probably started life sitting on a stone foundation on the ground. At a later date the church was lifted and had the current first floor added beneath it. The doorway appears to be of the original period of the church (1871), and to have been relocated to the new lower story. The original tower may have been only the first square section, but at some later date the second square and spire were likely added. I base this observation on fact that the second square section of the tower, and the spire, don’t start within the first section as is usually done (telescoping), but just sit on top of it. The architectural style is vernacular Greek Revival. Characteristic of this are the wide pilasters, closed pediment, and wide double frieze. There is an interesting projection, reflecting the position of the tower or a porch for the doorway, on the middle of the front wall. This is seen occasionally on Vermont churches. The Town Hall is of timber frame construction, spruce and hemlock, and measures about 36 x 48 in plan.