A Case-Study of the German Archaeologist Herbert Jankuhn (1905-1990)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Externsteine – Ähnliche Zuschreibungen in Der Öffent- Ein Denkmal Als Objekt Lichen Wahrnehmung Der Externsteine

„Kraftort“, „Kultplatz“, „Gestirnsheilig- tum“ – oftmals finden sich solche und Die Externsteine – ähnliche Zuschreibungen in der öffent- Ein Denkmal als Objekt lichen Wahrnehmung der Externsteine. wissenschaftlicher Forschung Vorstellungen von einem „vorchristli- und Projektionsfläche chen Kultort“ im Teutoburger Wald wur- den von Vertreterinnen und Vertretern völkischer Vorstellungen der völkischen Bewegung seit Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts popularisiert und Fachtagung im sind bis heute wirkmächtig. Ein Ziel der Lippischen Landesmuseum Detmold Fachtagung ist es, die Ursprünge, Funk- 6. und 7. März 2015 tionen und Rezeption der völkischen Mythenbildung an den Externsteinen zu beleuchten. In einem zweiten Tagungsschwerpunkt stellen Wissenschaftlerinnen und Wis- Teilnahmegebühr 10,00 Euro, senschaftler verschiedener Fachdiszipli- ermäßigt 8,00 Euro nen den aktuellen Forschungsstand zur Geschichte der Externsteine-Anlagen Die Teilnehmerzahl ist begrenzt, um den Mythen gegenüber. Damit wird Anmeldung bis zum 20.2.2015 wird eines der bedeutendsten Denkmäler gebeten. Westfalens erstmals interdisziplinär ge- Kontakt: würdigt. Lippisches Landesmuseum Detmold Im Rahmen der Tagung zeigt das Lip- Ameide 4 32756 Detmold pische Landesmuseum Karen Russos [email protected] Film „Externsteine“ (2012) und lädt zur anschließenden Diskussion mit der Tel. 05231/9925-19 Londoner Regisseurin ein. Die Tagung wird veranstaltet von: Mit freundlicher Unterstützung durch: Lippisches Landesmuseum Detmold Stiftung Standortsicherung Kreis Lippe Schutzgemeinschaft -

A Possible Ring Fort from the Late Viking Period in Helsingborg

A POSSIBLE RING FORT FROM THE LATE VIKING PERIOD IN HELSINGBORG Margareta This paper is based on the author's earlier archaeologi- cal excavations at St Clemens Church in Helsingborg en-Hallerdt Weidhag as well as an investigation in rg87 immediately to the north of the church. On this occasion part of a ditch from a supposed medieval ring fort, estimated to be about a7o m in diameter, was unexpectedly found. This discovery once again raised the question as to whether an early ring fort had existed here, as suggested by the place name. The probability of such is strengthened by the newly discovered ring forts in south-western Scania: Borgeby and Trelleborg. In terms of time these have been ranked with four circular fortresses in Denmark found much earlier, the dendrochronological dating of which is y8o/g8r. The discoveries of the Scanian ring forts have thrown new light on south Scandinavian history during the period AD yLgo —zogo. This paper can thus be regarded as a contribution to the debate. Key words: Viking Age, Trelleborg-type fortress, ri»g forts, Helsingborg, Scania, Denmark INTRODUCTION Helsingborg's location on the strait of Öresund (the Sound) and its special topography have undoubtedly been of decisive importance for the establishment of the town and its further development. Opinions as to the meaning of the place name have long been divided, but now the military aspect of the last element of the name has gained the up- per. hand. Nothing in the find material indicates that the town owed its growth to crafts, market or trade activity. -

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021 SAMPLE OF PROGRAM* Day 1: Friday, May 21, 2021 Arrival in Paris on your own Group Welcome Dinner in a restaurant Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 2: Saturday May 22, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris. Guided visit of the church of St Pierre de Montmartre, one of the oldest extant churches in Paris, and the Sacré Coeur Basilica with its mosaic of Christ in Glory. Lunch on your own in historic Montmartre After lunch, meet your tour bus for a guided visit of the St Denis Basilica to learn about the birth of Gothic architecture Return to the hotel at the end of the day. Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 3: Sunday, May 23, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and your 2 guides in front of your hotel for a day trip to Chartres. Guided tour of Notre Dame de Chartres Cathedral, a unique example of early gothic architecture, th and its 13 century Labyrinth Group Lunch in a restaurant Free time to explore the town of Chartres Return to Paris with your tour bus at the end of the day Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 4: Monday, May 24, 2021 Meet your 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris (transport pass provided) Guided visit of Notre Dame Cathedral (the exterior), an iconic masterpiece of Gothic architecture, ravaged by fire in April 2019. -

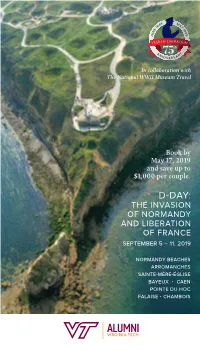

2019 Flagship Vatech Sept5.Indd

In collaboration with The National WWII Museum Travel Book by May 17, 2019 and save up to $1,000 per couple. D-DAY: THE INVASION OF NORMANDY AND LIBERATION OF FRANCE SEPTEMBER 5 – 11, 2019 NORMANDY BEACHES ARROMANCHES SAINTE-MÈRE-ÉGLISE BAYEUX • CAEN POINTE DU HOC FALAISE • CHAMBOIS NORMANDY CHANGES YOU FOREVER Dear Alumni and Friends, Nothing can match learning about the Normandy landings as you visit the ery places where these events unfolded and hear the stories of those who fought there. The story of D-Day and the Allied invasion of Normandy have been at the heart of The National WWII Museum’s mission since they opened their doors as The National D-Day Museum on June 6, 2000, the 56th Anniversary of D-Day. Since then, the Museum in New Orleans has expanded to cover the entire American experience in World War II. The foundation of this institution started with the telling of the American experience on D-Day, and the Normandy travel program is still held in special regard – and is considered to be the very best battlefield tour on the market. Drawing on the historical expertise and extensive archival collection, the Museum’s D-Day tour takes visitors back to June 6, 1944, through a memorable journey from Pegasus Bridge and Sainte-Mère-Église to Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc. Along the way, you’ll learn the timeless stories of those who sacrificed everything to pull-off the largest amphibious attack in history, and ultimately secured the freedom we enjoy today. Led by local battlefield guides who are experts in the field, this Normandy travel program offers an exclusive experience that incorporates pieces from the Museum’s oral history and artifact collections into presentations that truly bring history to life. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

The Significance of Dehumanization: Nazi Ideology and Its Psychological Consequences

Politics, Religion & Ideology ISSN: 2156-7689 (Print) 2156-7697 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ftmp21 The Significance of Dehumanization: Nazi Ideology and Its Psychological Consequences Johannes Steizinger To cite this article: Johannes Steizinger (2018): The Significance of Dehumanization: Nazi Ideology and Its Psychological Consequences, Politics, Religion & Ideology To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2018.1425144 © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 24 Jan 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ftmp21 POLITICS, RELIGION & IDEOLOGY, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2018.1425144 The Significance of Dehumanization: Nazi Ideology and Its Psychological Consequences Johannes Steizinger Department of Philosophy, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria ABSTRACT Several authors have recently questioned whether dehumanization is a psychological prerequisite of mass violence. This paper argues that the significance of dehumanization in the context of National Socialism can be understood only if its ideological dimension is taken into account. The author concentrates on Alfred Rosenberg’s racist doctrine and shows that Nazi ideology can be read as a political anthropology that grounds both the belief in the German privilege and the dehumanization of the Jews. This anthropological framework combines biological, cultural and metaphysical aspects. Therefore, it cannot be reduced to biologism. This new reading of Nazi ideology supports three general conclusions: First, the author reveals a complex strategy of dehumanization which is not considered in the current psychological debate. -

Paper Number: 2860 Claims on the Past: Cave Excavations by the SS Research and Teaching Community “Ahnenerbe” (1935–1945) Mattes, J.1

Paper Number: 2860 Claims on the Past: Cave Excavations by the SS Research and Teaching Community “Ahnenerbe” (1935–1945) Mattes, J.1 1 Department of History, University of Vienna, Universitätsring 1, 1010 Wien, Austria, [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Founded in 1935 by a group of fascistic scholars and politicians around Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, the “Ahnenerbe” proposed to research the cultural history of the Aryan race and to legitimate the SS ideology and Himmler’s personal interest in occultism scientifically. Originally organized as a private society affiliated to Himmler’s staff, the “Ahnenerbe” became one of the most powerful institutions in the Third Reich engaged with questions of archaeology, cultural heritage and politics. Its staff were SS members, consisting of scientific amateurs, occultists as well as established scholars who obtained the rank of an officer. Competing against the “Amt Rosenberg”, an official agency for cu ltural policy and surveillance in Nazi Germany, the research community “Ahnenerbe” had already become interested in caves and karst as excellent sites for fossil man investigations before 1937/38, when Himmler founded his own Department of Karst- and Cave Research within the “Ahnenerbe”. Extensive excavations in several German caves near Lonetal (G. Riek, R. Wetzel, O. Völzing), Mauern (R.R. Schmidt, A. Bohmer), Scharzfeld (K. Schwirtz) and Leutzdorf (J.R. Erl) were followed by research travels to caves in France, Spain, Ukraine and Iceland. After the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in 1939, the “Ahnenerbe” even planned the appropriation of all Moravian caves to prohibit the excavations of local prehistorians and archaeologists from the “Amt Rosenberg”, who had to switch for their excavations to Figure 1: Prehistorian and SS- caves in Thessaly (Greece). -

Heimskringla III.Pdf

SNORRI STURLUSON HEIMSKRINGLA VOLUME III The printing of this book is made possible by a gift to the University of Cambridge in memory of Dorothea Coke, Skjæret, 1951 Snorri SturluSon HE iMSKrinGlA V oluME iii MAG nÚS ÓlÁFSSon to MAGnÚS ErlinGSSon translated by AliSon FinlAY and AntHonY FAulKES ViKinG SoCiEtY For NORTHErn rESEArCH uniVErSitY CollEGE lonDon 2015 © VIKING SOCIETY 2015 ISBN: 978-0-903521-93-2 The cover illustration is of a scene from the Battle of Stamford Bridge in the Life of St Edward the Confessor in Cambridge University Library MS Ee.3.59 fol. 32v. Haraldr Sigurðarson is the central figure in a red tunic wielding a large battle-axe. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ vii Sources ............................................................................................. xi This Translation ............................................................................. xiv BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES ............................................ xvi HEIMSKRINGLA III ............................................................................ 1 Magnúss saga ins góða ..................................................................... 3 Haralds saga Sigurðarsonar ............................................................ 41 Óláfs saga kyrra ............................................................................ 123 Magnúss saga berfœtts .................................................................. 127 -

Instrumentalising the Past: the Germanic Myth in National Socialist Context

RJHI 1 (1) 2014 Instrumentalising the Past: The Germanic Myth in National Socialist Context Irina-Maria Manea * Abstract : In the search for an explanatory model for the present or even more, for a fundament for national identity, many old traditions were rediscovered and reutilized according to contemporary desires. In the case of Germany, a forever politically fragmented space, justifying unity was all the more important, especially beginning with the 19 th century when it had a real chance to establish itself as a state. Then, beyond nationalism and romanticism, at the dawn of the Third Reich, the myth of a unified, powerful, pure people with a tradition dating since time immemorial became almost a rule in an ideology that attempted to go back to the past and select those elements which could have ensured a historical basis for the regime. In this study, we will attempt to focus on two important aspects of this type of instrumentalisation. The focus of the discussion is mainly Tacitus’ Germania, a work which has been forever invoked in all sorts of contexts as a means to discover the ancient Germans and create a link to the modern ones, but in the same time the main beliefs in the realm of history and archaeology are underlined, so as to catch a better glimpse of how the regime has been instrumentalising and overinterpreting highly controversial facts. Keywords : Tacitus, Germania, myth, National Socialism, Germany, Kossinna, cultural-historical archaeology, ideology, totalitarianism, falsifying history During the twentieth century, Tacitus’ famous work Germania was massively instrumentalised by the Nazi regime, in order to strengthen nationalism and help Germany gain an aura of eternal glory. -

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

Rådhuspladsen Metro Cityring Project

KØBENHAVNS MUSEUM MUSEUM OF COPENHAGEN / ARCHAEOLOGICAL REPORT Rådhuspladsen Metro Cityring Project KBM 3827, Vestervold Kvarter, Københavns Sogn Sokkelund Herred, Københavns Amt Kulturstyrelsen j.nr.: 2010-7.24.02/KBM-0015 Ed Lyne & Hanna Dahlström Contributions by Camilla Haarby Hansen Metro Cityring - Rådhuspladsen KBM 3827, Excavation Report Museum of Copenhagen Vesterbrogade 59 1620 København V Telefon: +45 33 21 07 72 Fax: +45 33 25 07 72 E-mail: [email protected] www.copenhagen.dk Cover picture: The Rådhuspladsen excavation, with Area 4 (foreground) and Area 5 open. Taken from the fourth floor of Politikens Hus (with kind permission), July 13th 2012 © Museum of Copenhagen 2015 ii Museum of Copenhagen 2015 Metro Cityring - Rådhuspladsen KBM 3827, Excavation Report Contents Abstract v 1 Introduction 1 2 Administrative data 8 3 Topography and cultural historical background 13 4 Archaeological background 23 5 Objectives and aims 30 6 Methodology, documentation, organisation and procedures 41 7 Archaeological results 62 Phase 1 Early urban development – AD 1050-1250 65 Phase 2 Urban consolidation – AD 1250-1350 128 Phase 3 Urban consolidation and defence – AD 1350-1500 170 Phase 4 Expansion of defences and infrastructure – AD 1500-1600 185 Phase 5 Decommissioning of the medieval defences; and the mill by Vesterport – AD 1600- c. 1670 223 Phase 6 The final phase of fortifications – c. AD 1670- c.1860 273 Phase 7 The modern city – AD 1860- present day 291 8 Assessment of results and future research potential 303 9 Future site potential -

The Hostages of the Northmen: from the Viking Age to the Middle Ages

Part IV: Legal Rights It has previously been mentioned how hostages as rituals during peace processes – which in the sources may be described with an ambivalence, or ambiguity – and how people could be used as social capital in different conflicts. It is therefore important to understand how the persons who became hostages were vauled and how their new collective – the new household – responded to its new members and what was crucial for his or her status and participation in the new setting. All this may be related to the legal rights and special privileges, such as the right to wear coat of arms, weapons, or other status symbols. Personal rights could be regu- lated by agreements: oral, written, or even implied. Rights could also be related to the nature of the agreement itself, what kind of peace process the hostage occurred in and the type of hostage. But being a hostage also meant that a person was subjected to restric- tions on freedom and mobility. What did such situations meant for the hostage-taking party? What were their privileges and obli- gations? To answer these questions, a point of departure will be Kosto’s definition of hostages in continental and Mediterranean cultures around during the period 400–1400, when hostages were a form of security for the behaviour of other people. Hostages and law The hostage had its special role in legal contexts that could be related to the discussion in the introduction of the relationship between religion and law. The views on this subject are divided How to cite this book chapter: Olsson, S.