Not Diamonds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Timber Depredations in Montana to 1900

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1967 Analysis of timber depredations in Montana to 1900 Edward Bernie Butcher The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Butcher, Edward Bernie, "Analysis of timber depredations in Montana to 1900" (1967). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4709. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4709 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / 7y AN ANALYSIS OF TIMBER DEPREDATIONS IN MONTANA TO 1900 by Edward Bernie Butcher B. S. Eastern Montana College, 1965 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1967 Approved by: (fhe&d j Chairman, Board of Examiners Deaf, Graduate School JU N 1 9 1967 Date UMI Number: EP40173 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP40173 Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Clark and Daly - a Personality Analysis

The topper King?: Clark and Daly - A Personality Analysis A Thesis Presented to the Department of History, Carroll College, In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors By Michael D. Walsh * \ March 1975 CORETTE LIBRARY CARROI I mi I cr.c 5962 00082 610 CARROLL COLLEGE LIBRARY HELENA, MONTANA 596QH SIGNATURE PAGE This thesis for honors recognition has been approved for the Department of History. 7 rf7ir ....... .................7 ' Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For assistance in my research I wish to thank the staff of the Montana Historical Society Library. I would like to thank my mother who typed this paper and my father who provided the copies. My thanks to Cynthia Rubel and Michael Shields who served as proof readers. I am also grateful to Reverend Eugene Peoples,Ph.D., and Dr. William Lang who read this thesis and offered help ful suggestions. Finally, my thanks to Reverend William Greytak,Ph.D, my director, for h1s criticism, guidance and encouragement which helped me to complete this work. CONTENTS Chapter 1. Their Contemporaries.................................... 1 Chapter 2. History’s Viewpoint ..................................... 13 Chapter 3. Correspondence and Personal Reflections . .................... ....... 24 Bibliography 32 CHAPTER 1 Their Contemporaries In 1809 the territory of Montana was admitted to the Union as the forty-first state, With this act Montana now had to concern herself with the elections of public officials and the selection of a location for the capital. For the next twelve years these political issues would provide the battleground for two men, fighting for supremacy in the state; two men having contributed considerably to the development of Montana (prior to 1889) would now subject her to twelve years of political corruption, William Andrew Clark, a migrant from Pennsylvania, craved the power which would be his if he were to become the senator from Montana. -

![Hamilton, a Legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An Historical Pageant- Drama of Hamilton, Mont.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4511/hamilton-a-legacy-for-the-bitterroot-valley-an-historical-pageant-drama-of-hamilton-mont-1044511.webp)

Hamilton, a Legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An Historical Pageant- Drama of Hamilton, Mont.]

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1959 Hamilton, a legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An historical pageant- drama of Hamilton, Mont.] Donald William Butler The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Butler, Donald William, "Hamilton, a legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An historical pageant-drama of Hamilton, Mont.]" (1959). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2505. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2505 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HAMILTON A LEGACY FOR THE BITTERROOT VALLEY by DONALD WILLIAM BUTLER B.A. Montana State University, 1949 Presented in partial f-ulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1959 Approved by; / t*-v« ^—— Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School AUG 1 7 1959 Date UMI Number: EP34131 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT UMI EP34131 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE til NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN //OW 7~O COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC MARCUS DALY MEMORIAL HOSPITAL AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER 211 SOUTH FOURTH STREET —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT HAMILTON __.VICINITY OF #1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE MONTANA 30 RAVALLI 081 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _XuiLDING(S) _?PRIVATE X_UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY X.OTHER:TO BE OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME JEROME BORKOSKI STREETS, NUMBER p> Q> g^ ^ C.TY.TOWN HAMILTON STATE __ VICINITY OF MONTANA i LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. RAVALLI COUNTY COURTHOUSE STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE HAMILTON MONTANA REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS NONE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE _COUNTY __LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED X.UNALTERED X ORIGINAL SITE —RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Marcus Daly Hospital is one of the most impressive structures in the entire Bitterroot Valley. Construction on the structure, considered to b( the most fireproof possible, began in August, 1930. The design was pre pared by H. E. Kirkemo, architect, of Missoula, Montana. -

100Years the Antiquities Act 1906-2006 the National Historic Preservation Act 1966-2006 of Preservation

100years the antiquities act 1906-2006 the national historic preservation act 1966-2006 of preservation photographs by jack e. boucher and jet lowe PillarOF PRESERVATION celebrating four decades of the national historic preservation act “I was dismayed to learn from reading this report that almost half of the 12,000 structures list- ed in the Historic American Buildings Survey of the National Park Service have already been destroyed,” writes Lady Bird Johnson in the foreword to With Heritage So Rich, the call to arms pub- lished in tandem with the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. Urban renewal seemed unstoppable in the early ’60s. Pennsylvania Avenue, deemed dowdy by President Kennedy during his inaugural parade, was slated for a makeover by modernist architects. “The champions of modern architecture seldom missed an opportunity to ridicule the past,” historian Richard Longstreth wrote in these pages a few years ago, reassessing the era. “Buildings and cities created since the rise of industrial- ization were charged with having nearly ruined the planet. The legacy of one’s parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents was not only visually meaningless and degenerate, but socially and spiritually repres- sive as well.” Against this tide, a generation rose up, giving birth to a populist movement. Here, Common Ground salutes what was saved, and what was lost. Right: The National Archives, along Pennsylvania Avenue. 28 COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2006 COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2006 29 30 COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2006 FAR LEFT AND BELOW JET LOWE/NPS/HAER, JACK E. BOUCHER/NPS/HAER FAR The National Historic Preservation Act—embracing the full breadth of sites integral to the nation’s story—reflects a dynamic vision of the past and the ingredients that make it matter. -

S Involvement in Chilean to the Department of History in Candidacy for the Degree of Helena, Montana

CARROLL COLLEGE LAS POLITICAS DEL COBRE: A STUDY OF THE ANACONDA COMPANY’S INVOLVEMENT IN CHILEAN POLITICS 1969-1973 A THESIS SUBMITED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF HONORS GRADUATE BY REBECCA ELLIS HELENA, MONTANA MAY 2003 SIGNATURE PAGE This thesis for honors recognition has been approved for the Department of History Dr. Tomas Graman CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................................... iii CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................. 1 Goals of Study 2. THE PRE-ALLENDE YEARS IN AND OUT OF CHILE.....................5 An examination of political factors operating in Chile prior to the election of Salvador Allende The reaction of the United States Government to the election of Allende The political history of the Anaconda Company The history of the Anaconda Company’s operations in Chile 3. THE PREVENTIVE PERIOD.................................................................19 The Anaconda Company’s efforts to prevent, first the election of Allende and then the nationalization of copper, in conjunction with the United States government The Anaconda Company’s efforts in conjunction with other multinational corporations operating in Chile and facing the threat of nationalization The Company’s powers of influence over Chile as derived from the company’s internal structure 4. THE CONTROL PERIOD......................................................................32 Anaconda’s efforts to gain compensation -

'Liberty'cargo Ship

‘LIBERTY’ CARGO SHIP FEATURE ARTICLE written by James Davies for KEY INFORMATION Country of Origin: United States of America Manufacturers: Alabama Dry Dock Co, Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards Inc, California Shipbuilding Corp, Delta Shipbuilding Co, J A Jones Construction Co (Brunswick), J A Jones Construction Co (Panama City), Kaiser Co, Marinship Corp, New England Shipbuilding Corp, North Carolina Shipbuilding Co, Oregon Shipbuilding Corp, Permanente Metals Co, St Johns River Shipbuilding Co, Southeastern Shipbuilding Corp, Todd Houston Shipbuilding Corp, Walsh-Kaiser Co. Major Variants: General cargo, tanker, collier, (modifications also boxed aircraft transport, tank transport, hospital ship, troopship). Role: Cargo transport, troop transport, hospital ship, repair ship. Operated by: United States of America, Great Britain, (small quantity also Norway, Belgium, Soviet Union, France, Greece, Netherlands and other nations). First Laid Down: 30th April 1941 Last Completed: 30th October 1945 Units: 2,711 ships laid down, 2,710 entered service. Released by WW2Ships.com USA OTHER SHIPS www.WW2Ships.com FEATURE ARTICLE 'Liberty' Cargo Ship © James Davies Contents CONTENTS ‘Liberty’ Cargo Ship ...............................................................................................................1 Key Information .......................................................................................................................1 Contents.....................................................................................................................................2 -

Marcus Daly, Orin Onibmgrant

e THE EKALAKA EAGLE WOMAN INFORMS);MONTANA'S FORST CAPTAIN OF INDUSTRY FORTUNE AWAITS PEN FOR LOVER SON OF MONTAN ORIN ONIBMGRANT LAD SEVEN MILLIONS ESTIMA SWEET- DALY, LOO'rEB BANK FOR WAS [MARCUS VALUE OF HERITAGE PHIL- HEART WHO INFORMED ON HALF CASTE. Hills IPPINE $ HIM FOR REWARD few days ago occurred the Bars and twenty-fifth anniversary of Then follows names of -placer Father Went to Islands as Soldier Of Tale of John D. Sykes, Who Was the death of Marcus Daly, workers and their production, such Montana Volunteers; Married mad Sad pros- Caught in the Sun River Country father of the copper mining in- as: "Last Chance, average Died There; Meantime 011 Struck Bar, a Short Time Ago, a Fugitive from dustry in Montana. He came to' pect, per pan 10 cents. Iowa on His Land. Justice. this country in his early youth, average pan, 3 cents. Sage Bruch alone, an Irish lad, and fought for 5 cents. Deep Bar, 1 to 3 cents," Press dispatches to the effect that pan Oregano Velasquez Carmichael, 18, "Arms and the man—" so be- his livelihood on the streets of New while "Short Bar" is credited with heir to a ;7,000,000 estate in Okla- gins an ancient classic. This is a York City. He died an empire having produced 10 cents per pan. homa, had been located in an inland tale of arms and the man, dice and builder, master of a great industry. boast was in its village in the Philippine islands, has the woman. The district's served to revive memories in the Ile was the direct cause of a dis- ditches for washing gold. -

Citizens United, Caperton, and the War of the Copper Kings Larry Howell Alexander Blewett I I School of Law at the University of Montana, [email protected]

Alexander Blewett III School of Law at the University of Montana The Scholarly Forum @ Montana Law Faculty Law Review Articles Faculty Publications 2012 Once Upon a Time in the West: Citizens United, Caperton, and the War of the Copper Kings Larry Howell Alexander Blewett I I School of Law at the University of Montana, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.umt.edu/faculty_lawreviews Part of the Election Law Commons Recommended Citation Larry Howell, Once Upon a Time in the West: Citizens United, Caperton, and the War of the Copper Kings , 73 Mont. L. Rev. 25 (2012), Available at: http://scholarship.law.umt.edu/faculty_lawreviews/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at The choS larly Forum @ Montana Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Law Review Articles by an authorized administrator of The choS larly Forum @ Montana Law. ARTICLES ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST: CITIZENS UNITED, CAPERTON, AND THE WAR OF THE COPPER KINGS Larry Howell* He is said to have bought legislaturesand judges as other men buy food and raiment. By his example he has so excused and so sweetened corruption that in Montana it no longer has an offensive smell. -Mark Twain' [T]he Copper Kings are a long time gone to their tombs. -District Judge Jeffrey Sherlock 2 I. INTRODUCTION Recognized by even its strong supporters as "one of the most divisive decisions" by the United States Supreme Court in years,3 Citizens United v. * Associate Professor, The University of Montana School of Law. -

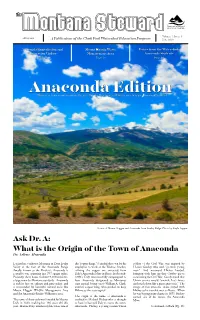

2019 Anaconda Edition

Volume 7, Issue 1 cfwep.org A Publication of the Clark Fork Watershed Education Program July, 2019 AnacondaAnaconda Remediation and Mount Haggin Waste Voices from the Watershed: Restoration Update Management Area Anaconda Students Page 5 Page 10 Page 12 AnacondaThis is part two in our watershed series. For the Headwaters Edition Edition see cfwep.org/montana-steward A view of Mount Haggin and Anaconda from Stucky Ridge. Photo by Kayla Lappin. Ask Dr. A: What is the Origin of the Town of Anaconda Dr. Arlene Alvarado Located in southwest Montana in Deer Lodge the “copper kings,” founded the town for his soldier of the Civil War, was inspired by Valley at the foot of the Anaconda Range employees to work at the Washoe Smelter, Horace Greeley, who said, “go west, young (locally known as the Pintler’s), Anaconda is refining the copper ore extracted from man.” And westward Hickey headed, a small town, spanning just 737 square miles. Daly’s Anaconda Mine in Butte. In the mid- bringing with him another Greeley quote Presently, she is home to about 9,100 residents, 1890’s, Daly unsuccessfully campaigned to concerning the Civil War. Greely stated that a large town by Montana standards. Anaconda have Anaconda designated as Montana’s Union armies would “encircle Lee’s forces is rich in history, culture and personality, and state capital, losing out to William A. Clark, and crush them like a giant anaconda.” The is surrounded by beautiful natural areas like another copper king, who pushed to keep image of this awesome snake stayed with Mount Haggin Wildlife Management Area Helena as the state capital. -

Classic American Currency

CLASSIC AMERICAN CURRENCY NEW-YORK WATER WORKS NOTE * 399 New-York Water Works eight shil- * 400 ling note. 3 5/8” x 2 1/8”. New York. Pennsylvania three pence note. 2 5/ FIRST PAUL REVERE PRINTING OF January 6, 1776. Attractive vi- 8”x 2 7/8” Pennsylvania. April 20, MASSACHUSETTS NOTES, USED TO PAY THE gnette of verso. This third and fi- 1781. A scare, late issue plate b PATRIOTS WHO SERVED AT BUNKER HILL nal Water Works issue of January printing. About Extremely Fine. 6, 1776 is highly popular among $300 - up * 398 collectors due to its attractive de- Colony of Massachusetts Bay note for ten shillings. 7” x 3 5/8”. sign and fine reserve vignette. This Massachusetts. May 25, 1775. This note, part of the first emis- item has been encapsulated and sion printed by iconic American patriot Paul Revere, bears the graded by PASS-CO. CU-61 signature of Henry Gardner, the Receiver General of Massachu- $400 - up setts. Following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Provincial Congress of MA authorized an emission of £25, 998 in “Sol- diers’ Notes” in order to raise an army. These notes, the first emission printed by Paul Revere, were paid to the men who soon found themselves facing British regulars at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Working night and day, Revere threw himself into this task, at time under the watchful eye of two member of congress. Moreover, the plate used for ten shilling notes in this emission was the backside of a recycled plate that had originally been used for Revere’s famous print of the Boston Massacre. -

MISSOULA DAY TRIPS National Bison Range Explore the Bitterroot

MISSOULA DAY TRIPS A short day trip out of Missoula can bring you to fly-fishing hot-spots, wildlife watching, small town charm and so much more. Natural hot springs hide in breathtaking forests, NATIONAL while bison roam one of the oldest wildlife refuges in the nation. You won’t need to travel BISON RANGE far, we’re surrounded. Find your next epic day trip out of Missoula here, or take a look at some of our favorites: National Bison Range • One of Montana’s best kept secrets sits 50 miles north of Missoula. • The National Bison Range, National Wildlife Refuge, is home to an impressive number of different species. See the iconic bison, as well as deer, elk, bighorn sheep and more all while taking in the stunning views of the Mission Mountain Range. • On your way back to Missoula, be sure to stop by the Garden of One Thousand Buddhas, a tranquil spot to take in the peace and calmness of the Western Rockies. • For a sweet treat, stop at Windmill Village Bakery along Highway 93 for some seriously scrumptious doughnuts. Explore the Bitterroot • The Bitterroot Valley is home to charming small communities and big, beautiful mountain views. Head south down US Highway 93 for some good ole fashioned Montana fun, stopping to explore the quaint communities along the way. • In Lolo, be sure to check out Travelers’ Rest State Park which is rich in history and Native American culture and a pivotal site of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Lolo Peak Brewing Co. serves up great food and craft beer nearby.