Analysis of Timber Depredations in Montana to 1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clark and Daly - a Personality Analysis

The topper King?: Clark and Daly - A Personality Analysis A Thesis Presented to the Department of History, Carroll College, In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors By Michael D. Walsh * \ March 1975 CORETTE LIBRARY CARROI I mi I cr.c 5962 00082 610 CARROLL COLLEGE LIBRARY HELENA, MONTANA 596QH SIGNATURE PAGE This thesis for honors recognition has been approved for the Department of History. 7 rf7ir ....... .................7 ' Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For assistance in my research I wish to thank the staff of the Montana Historical Society Library. I would like to thank my mother who typed this paper and my father who provided the copies. My thanks to Cynthia Rubel and Michael Shields who served as proof readers. I am also grateful to Reverend Eugene Peoples,Ph.D., and Dr. William Lang who read this thesis and offered help ful suggestions. Finally, my thanks to Reverend William Greytak,Ph.D, my director, for h1s criticism, guidance and encouragement which helped me to complete this work. CONTENTS Chapter 1. Their Contemporaries.................................... 1 Chapter 2. History’s Viewpoint ..................................... 13 Chapter 3. Correspondence and Personal Reflections . .................... ....... 24 Bibliography 32 CHAPTER 1 Their Contemporaries In 1809 the territory of Montana was admitted to the Union as the forty-first state, With this act Montana now had to concern herself with the elections of public officials and the selection of a location for the capital. For the next twelve years these political issues would provide the battleground for two men, fighting for supremacy in the state; two men having contributed considerably to the development of Montana (prior to 1889) would now subject her to twelve years of political corruption, William Andrew Clark, a migrant from Pennsylvania, craved the power which would be his if he were to become the senator from Montana. -

Brief on Merits of Echols, Et

No. 02-1676 and consolidated cases IN THE Supreme Court o f the United States FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION, et al. Appellants vs. SENATOR MITCH MCCONNELL, et al. Appellees. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia Joint Brief on the Merits of Appellees Emily Echols and Barret Austin O’Brock, et al., Urging Affirmance of the Judgment that BCRA Section 318 is Unconstitutional JAMES BOPP, JR. JAY ALAN SEKULOW RICHARD E. COLESON Counsel of Record THOMAS J. MARZEN JAMES M. HENDERSON, SR. JAMES MADISON CENTER STUART J. ROTH FOR FREE SPEECH COLBY M. MAY BOPP, COLESON & BOSTROM JOEL H. THORNTON 1 South 6th Street WALTER M. WEBER Terre Haute, IN 47807-3510 AMERICANCENTER FOR LAW (812) 232-2434 & JUSTICE 201 Maryland Avenue NE Attorneys for Appellee Barrett Washington, DC 20002-5703 Austin O’Brock (202) 546-8890 Attorneys for Appellees Emily Echols, et al. APPELLEES’ COUNTER-STATEMENT OF QUESTION PRESENTED Prior to the effective date of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA), Pub. L. No. 107-155, 116 Stat. 81, minors had the right to contribute to the committees of political parties and to candidates for federal office, subject to the same limitations that also applied to persons who had attained their majority. Section 318 of BCRA completely prohibits donations to committees and to candidates by minors. In the view of these Appellees, all of whom are minors, the question presented is: Whether the three judge district court erred in its judgment that the absolute ban on donations by minors was unconstitutional? (i) PARTIES These Appellees incorporate by reference the listing of the parties set out in the Jurisdictional Statement of the FEC, et al., at II-IV. -

![Hamilton, a Legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An Historical Pageant- Drama of Hamilton, Mont.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4511/hamilton-a-legacy-for-the-bitterroot-valley-an-historical-pageant-drama-of-hamilton-mont-1044511.webp)

Hamilton, a Legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An Historical Pageant- Drama of Hamilton, Mont.]

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1959 Hamilton, a legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An historical pageant- drama of Hamilton, Mont.] Donald William Butler The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Butler, Donald William, "Hamilton, a legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An historical pageant-drama of Hamilton, Mont.]" (1959). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2505. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2505 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HAMILTON A LEGACY FOR THE BITTERROOT VALLEY by DONALD WILLIAM BUTLER B.A. Montana State University, 1949 Presented in partial f-ulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1959 Approved by; / t*-v« ^—— Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School AUG 1 7 1959 Date UMI Number: EP34131 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT UMI EP34131 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. -

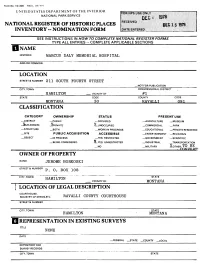

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE til NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN //OW 7~O COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC MARCUS DALY MEMORIAL HOSPITAL AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER 211 SOUTH FOURTH STREET —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT HAMILTON __.VICINITY OF #1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE MONTANA 30 RAVALLI 081 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _XuiLDING(S) _?PRIVATE X_UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY X.OTHER:TO BE OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME JEROME BORKOSKI STREETS, NUMBER p> Q> g^ ^ C.TY.TOWN HAMILTON STATE __ VICINITY OF MONTANA i LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. RAVALLI COUNTY COURTHOUSE STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE HAMILTON MONTANA REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS NONE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE _COUNTY __LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED X.UNALTERED X ORIGINAL SITE —RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Marcus Daly Hospital is one of the most impressive structures in the entire Bitterroot Valley. Construction on the structure, considered to b( the most fireproof possible, began in August, 1930. The design was pre pared by H. E. Kirkemo, architect, of Missoula, Montana. -

100Years the Antiquities Act 1906-2006 the National Historic Preservation Act 1966-2006 of Preservation

100years the antiquities act 1906-2006 the national historic preservation act 1966-2006 of preservation photographs by jack e. boucher and jet lowe PillarOF PRESERVATION celebrating four decades of the national historic preservation act “I was dismayed to learn from reading this report that almost half of the 12,000 structures list- ed in the Historic American Buildings Survey of the National Park Service have already been destroyed,” writes Lady Bird Johnson in the foreword to With Heritage So Rich, the call to arms pub- lished in tandem with the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. Urban renewal seemed unstoppable in the early ’60s. Pennsylvania Avenue, deemed dowdy by President Kennedy during his inaugural parade, was slated for a makeover by modernist architects. “The champions of modern architecture seldom missed an opportunity to ridicule the past,” historian Richard Longstreth wrote in these pages a few years ago, reassessing the era. “Buildings and cities created since the rise of industrial- ization were charged with having nearly ruined the planet. The legacy of one’s parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents was not only visually meaningless and degenerate, but socially and spiritually repres- sive as well.” Against this tide, a generation rose up, giving birth to a populist movement. Here, Common Ground salutes what was saved, and what was lost. Right: The National Archives, along Pennsylvania Avenue. 28 COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2006 COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2006 29 30 COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2006 FAR LEFT AND BELOW JET LOWE/NPS/HAER, JACK E. BOUCHER/NPS/HAER FAR The National Historic Preservation Act—embracing the full breadth of sites integral to the nation’s story—reflects a dynamic vision of the past and the ingredients that make it matter. -

S Involvement in Chilean to the Department of History in Candidacy for the Degree of Helena, Montana

CARROLL COLLEGE LAS POLITICAS DEL COBRE: A STUDY OF THE ANACONDA COMPANY’S INVOLVEMENT IN CHILEAN POLITICS 1969-1973 A THESIS SUBMITED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF HONORS GRADUATE BY REBECCA ELLIS HELENA, MONTANA MAY 2003 SIGNATURE PAGE This thesis for honors recognition has been approved for the Department of History Dr. Tomas Graman CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................................... iii CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................. 1 Goals of Study 2. THE PRE-ALLENDE YEARS IN AND OUT OF CHILE.....................5 An examination of political factors operating in Chile prior to the election of Salvador Allende The reaction of the United States Government to the election of Allende The political history of the Anaconda Company The history of the Anaconda Company’s operations in Chile 3. THE PREVENTIVE PERIOD.................................................................19 The Anaconda Company’s efforts to prevent, first the election of Allende and then the nationalization of copper, in conjunction with the United States government The Anaconda Company’s efforts in conjunction with other multinational corporations operating in Chile and facing the threat of nationalization The Company’s powers of influence over Chile as derived from the company’s internal structure 4. THE CONTROL PERIOD......................................................................32 Anaconda’s efforts to gain compensation -

Montana Freemason

Montana Freemason Feburary 2013 Volume 86 Number 1 Montana Freemason February 2013 Volume 86 Number 1 Th e Montana Freemason is an offi cial publication of the Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Montana. Unless otherwise noted,articles in this publication express only the private opinion or assertion of the writer, and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the Grand Lodge. Th e jurisdiction speaks only through the Grand Master and the Executive Board when attested to as offi cial, in writing, by the Grand Secretary. Th e Editorial staff invites contributions in the form of informative articles, reports, news and other timely Subscription - the Montana Freemason Magazine information (of about 350 to 1000 words in length) is provided to all members of the Grand Lodge that broadly relate to general Masonry. Submissions A.F.&A.M. of Montana. Please direct all articles and must be typed or preferably provided in MSWord correspondence to : format, and all photographs or images sent as a .JPG fi le. Only original or digital photographs or graphics Reid Gardiner, Editor that support the submission are accepted. Th e Montana Freemason Magazine PO Box 1158 All material is copyrighted and is the property of Helena, MT 59624-1158 the Grand Lodge of Montana and the authors. [email protected] (406) 442-7774 Deadline for next submission of articles for the next edition is March 30, 2013. Articles submitted should be typed, double spaced and spell checked. Articles are subject to editing and Peer Review. No compensation is permitted for any article or photographs, or other materials submitted for publication. -

Hon. Lee Mantle,, of Butte

ADS GIVEN THE TRIBUNE, LARGEST CIRCULATION ONE VEAR ------------- $2.00 IN THE TRIBUNE. IN ADVANCE. VOL. 28. NO. 12. DILLON, MONTANA, FRIDAY, MARCH 20, 1908. PRICE FIVE CENTS. HON. LEE MANTLE,, OF BUTTE. F, illlliipiiiiiliilp IIII It' : lf|f É p . WORKING ON THE IRON MOUNTAIN. STEAM LAUNDRY IN NEW HANDS. iS Ä -y Boosting for Increased ProsperityMessrs. Charles Birden and Otto Leach Butte-Argenta Company is Keeping Outlook Growing Brighter for Lease the Laundry from Steadily at It— Going Down 450 in the Beaverhead Valley J. F. Wikidal. Feet, then Crosscut. a Railroad Over Divide Into J. F. Wikidal, who has been owner Tony French was in Dillon from Ar- ...........J the Salmon Country. Will Begin Tomorrow. md proprietor of the Dillon Steam gerita the first of the week. He reports Laundry the past several years, on J that the Butte-Argenta Mining company Tuesday of this week closed a deal with I is carrying on work at the Iron Moun McCUTCHEON STILL INTERESTED EVERYONE WILL ATTEND MEETING Charles Birden and Otto Leach to lease tain mine steadily. The water-power his plant to these two gentlemen for a plant has been completed, the Pelton gear— probably longer. wheel installed and test shows that it develops 154 horsepower. Prominent Speakers and Well-posted Messrs. Birden and Leach will take Some Ranchers are Said to Ask Too The engine and boiler, which were men W ill be Here from charge of the laundry the first of next Much for Right of Way Thru formerly at the mouth of the tunnel at Other Parts. -

H. Doc. 108-222

FIFTY-FIFTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1897, TO MARCH 3, 1899 FIRST SESSION—March 15, 1897, to July 24, 1897 SECOND SESSION—December 6, 1897, to July 8, 1898 THIRD SESSION—December 5, 1898, to March 3, 1899 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1897, to March 10, 1897 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—GARRET A. HOBART, of New Jersey PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—WILLIAM P. FRYE, of Maine SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—WILLIAM R. COX, of North Carolina SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—RICHARD J. BRIGHT, of Indiana SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—THOMAS B. REED, 1 of Maine CLERK OF THE HOUSE—ALEXANDER MCDOWELL, 2 of Pennsylvania SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—BENJAMIN F. RUSSELL, of Missouri DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—WILLIAM J. GLENN, of New York POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—J. C. MCELROY ALABAMA Thomas C. McRae, Prescott CONNECTICUT William L. Terry, Little Rock SENATORS SENATORS Hugh A. Dinsmore, Fayetteville John T. Morgan, Selma Stephen Brundidge, Searcy Orville H. Platt, Meriden Edmund W. Pettus, Selma Joseph R. Hawley, Hartford REPRESENTATIVES CALIFORNIA REPRESENTATIVES George W. Taylor, Demopolis SENATORS E. Stevens Henry, Rockville Jesse F. Stallings, 3 Greenville Stephen M. White, Los Angeles Nehemiah D. Sperry, New Haven Henry D. Clayton, 4 Eufaula George C. Perkins, Oakland Charles A. Russell, Killingly 5 T. S. Plowman, Talladega REPRESENTATIVES Ebenezer J. Hill, Norwalk 6 William F. Aldrich, Aldrich John A. Barham, Santa Rosa Willis Brewer, Hayneville Marion De Vries, Stockton DELAWARE John H. Bankhead, Fayette Samuel G. Hilborn, Oakland SENATORS Milford W. Howard, Fort Payne James G. -

Proquest Dissertations

The institutionalization of the United States Senate, 1789-1996 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors White, David Richard Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 19:50:51 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289137 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reptoduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text direcUy f^ the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, cotored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print t}leedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white % photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. -

Spoils of Statehood: Montana Communities in Conflict, 1888-1894

Portland State University PDXScholar History Faculty Publications and Presentations History 1-1-1987 Spoils of statehood: Montana communities in conflict, 1888-1894 William L. Lang Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/hist_fac Part of the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Lang, W. L. (1987). Spoils of statehood: Montana communities in conflict, 1888-1894. Montana: The Magazine Of Western History, 37(4), 34-45. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. ::: Anacondans.asorintown::: $5::moreMontana's - - :: billsoffice- ... toughs. in. ... topermanenthisHelena's .. trooped another, pockets,.. ... .... tocapital.boys . withreadyI the.. .. were railroadreportsfor. ...... The useready . conclusive . on.. ofstation ......w asilling"spies" ... the . tocapital.. and ..........Montanagreet at cor- work &,.......tfthe S 6<., J t .. < * t-- , - -49 11 \ 1., 9 83 < . opOltS of Statehood .< tW by William L. Lang C g Even vvithHelena's saloons andbars closed, rumorshad A > > st^5 circulatedall day about what the oppositionhad done and \ < ' $ BThatthey had planned. Runners scurriedfrom one down- \\< JG'% -4 2 among the electorate. Sharp-eyed informants directed y4tw t";f' a policemento suspectedbribers; they nabbedone with $200 { / 4 rl ruptible voters. Wild stories circulated: One ^Tarned that \+ /; | AnacondaCompany Pinkertons were on their way to dis- Vy , rupt the election in Helena. By four o clock, one hundred , Central pulled in, but the "Pinkertons" turned out to be - a troopof Anacondalawyers. -

PARK HOTEL, Shelf and Heavy Hardwap I BUTCHERS

MONTANA MATTERS. THE BILLING S HEJLAUD. ROCKWELL & TOVEY, Livingston is to have new Catholic HILLINGS. MONTANA. MAY 10. 1884. c h u rc h . MANUFACTURERS AND DEAI.ERS IN The Smith River round-up will begin be QROCKERV THE BEPUBLIOAN CONVENTION. tween the 15th and 20th inst. The Maidcnites will celebrate the 4th of July. C. 8. Fell will deliver the oration Lee Mantle and CoL W. F. Bandera to HARNESS and SADDLES, A run took place on the Belknap bank go to Chicago. recently, but tliat institution proved equal to the emergency. SADDLERY HARDWARE, The Old "War Horae" Pawing in the Val The Concord Cattle company, of Custer ley and Rejoioing in his Strength. county intend increasing the number of their herd to 14,000. In the Husbandman Paris Gibson rake Montana, Texas, Clieyenne and California Saddles. The Republican Convention commenced A N T ) » 8 ' into Caldwell Edwards for alleged sneering work at Bozeman on Friday, the 2nd inst., at the "Campbell ’ Vermont sheep. assembling at Seieth <fc Kruggs’ Hall, at Team, Coach, Stage and Buggy Harness Always on Hand. noon. Col. Sanders, Chairman of the Cen The Dillon Tribune says that Rev. Hugh tral Committee called the meeting to order. Duncan, Grand Master of Montana Masons, B. F. W hite, of Beaverhead, wus elected is slowly recovering from injuries received Wliip-Sticks, Stage Lashes, Spanish Bits, Buggy Whips, Saddle Cloths, temporary chairman and McIntyre of Fort three months ago. Horse Blankets, Cartridge Belts, Stirrups, Horse and Mule Col Benton, secretary, and subsequently the The school at Maiden was closed recently lars, Fancy Bridles, Cinches, Quirts, I lace, Driving, election of both gentlemen to those posi on account of the prevalence of diphtheria.