Chapter 39 – the Giant Stumbles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States District Court Southern District of Texas Houston Division

Case 4:10-md-02185 Document 113 Filed in TXSD on 02/14/11 Page 1 of 182 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION In re BP plc Securities Litigation No. 4:10-md-02185 Honorable Keith P. Ellison LEAD PLAINTIFFS NEW YORK AND OHIO’S CONSOLIDATED CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT FOR ALL PURCHASERS OF BP SECURITIES FROM JANUARY 16, 2007 THROUGH MAY 28, 2010 Case 4:10-md-02185 Document 113 Filed in TXSD on 02/14/11 Page 2 of 182 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................2 II. JURISDICTION AND VENUE ........................................................................................11 III. THE PARTIES ..................................................................................................................11 A. Plaintiffs .................................................................................................................11 B. Defendants .............................................................................................................12 C. Non-Party ...............................................................................................................17 IV. BACKGROUND ...............................................................................................................17 A. BP’s Relevant Operations ......................................................................................17 B. BP’s Process Safety Controls Were Deficient Prior to the Class Period ...............18 -

Superfund Sites Yield New Drugs/Tourist Attractions

Fact or Fiction? Jack W. Dini 1537 Desoto Way Livermore, CA 94550 E-mail: [email protected] Superfund Sites Yield New Drugs/Tourist Attractions In 1993, Travel and Leisure Magazine The 1.5-mile wide, 1,800-foot deep pit, fi ght migraines and cancer.4 ran an article on the Continental Divide. part of the nation’s largest Superfund site, In recent years, more than 40 small It was tough on Butte: “the ugliest spot in has been fi lling for the last 20 years with organisms have been discovered in the lake Montana - despite a spirited historic dis- a poisonous broth laced with heavy metals and these hold much potential for agricul- trict amid the rubble, the overall picture is and arsenic - a legacy of Butte’s copper ture and medicine. It’s even thought that desolate.” It called nearby Anaconda “a sad mining days. When mining offi cials aban- some of these organisms can be employed sack mining town dominated by a smelter doned the pit and stopped the pumps that to reclaim the lake and other similarly con- smokestack.”1 Today things are somewhat kept it dry, they opened the spigots to about taminated waters by neutralizing acidity different for these two sites. 3 million gallons of water per day. Today, and absorbing dissolved metals. the lake is about 850 feet deep and contains Andrea and Don Stierle and their col- Butte, Montana - Lake Berkeley more than 3 billion cubic feet of water.3 leagues have found a strain of the pitho- Edwin Dobb reports, “At one time Butte Lake Berkeley, also known as The myces fungi producing a compound that provided a third of the copper used in the Berkeley Pit, covers almost 700 acres of bonds to a receptor that causes migraines United States - all from a mining district the former open-pit copper mine. -

Analysis of Timber Depredations in Montana to 1900

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1967 Analysis of timber depredations in Montana to 1900 Edward Bernie Butcher The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Butcher, Edward Bernie, "Analysis of timber depredations in Montana to 1900" (1967). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4709. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4709 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / 7y AN ANALYSIS OF TIMBER DEPREDATIONS IN MONTANA TO 1900 by Edward Bernie Butcher B. S. Eastern Montana College, 1965 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1967 Approved by: (fhe&d j Chairman, Board of Examiners Deaf, Graduate School JU N 1 9 1967 Date UMI Number: EP40173 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP40173 Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Clark and Daly - a Personality Analysis

The topper King?: Clark and Daly - A Personality Analysis A Thesis Presented to the Department of History, Carroll College, In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors By Michael D. Walsh * \ March 1975 CORETTE LIBRARY CARROI I mi I cr.c 5962 00082 610 CARROLL COLLEGE LIBRARY HELENA, MONTANA 596QH SIGNATURE PAGE This thesis for honors recognition has been approved for the Department of History. 7 rf7ir ....... .................7 ' Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For assistance in my research I wish to thank the staff of the Montana Historical Society Library. I would like to thank my mother who typed this paper and my father who provided the copies. My thanks to Cynthia Rubel and Michael Shields who served as proof readers. I am also grateful to Reverend Eugene Peoples,Ph.D., and Dr. William Lang who read this thesis and offered help ful suggestions. Finally, my thanks to Reverend William Greytak,Ph.D, my director, for h1s criticism, guidance and encouragement which helped me to complete this work. CONTENTS Chapter 1. Their Contemporaries.................................... 1 Chapter 2. History’s Viewpoint ..................................... 13 Chapter 3. Correspondence and Personal Reflections . .................... ....... 24 Bibliography 32 CHAPTER 1 Their Contemporaries In 1809 the territory of Montana was admitted to the Union as the forty-first state, With this act Montana now had to concern herself with the elections of public officials and the selection of a location for the capital. For the next twelve years these political issues would provide the battleground for two men, fighting for supremacy in the state; two men having contributed considerably to the development of Montana (prior to 1889) would now subject her to twelve years of political corruption, William Andrew Clark, a migrant from Pennsylvania, craved the power which would be his if he were to become the senator from Montana. -

University of Montana Bulletin Bureau of Nines and Mintalluroy Series � No

UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA BULLETIN BUREAU OF NINES AND MINTALLUROY SERIES NO. 2 THE MONTANA STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND METALLURGY DIRECTORY MONTANA METAL AND COAL MINES STATE SCHOOL OF MINES BUTTE, MONTANA DECEMBER, 1919 STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND METALLURGY STAFF CLAPP, CHARLES H. Director and Geology PhD., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1910 ADAMI, ARTHUR E. Mining Engineer E. M., Montana State School of Mines, 1907 PULSIFER. H. B. - - - - - - - Metallurgy and Safety B. S., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1903; C.E., Armour Institute of Technology, 1915; M. S., University of Chicago, 1918. FOREWORD The purpose of this bulletin is to serve as a directory of all the metal and coal mining companies in the State of Montana. Although every effort possible by correspondence was made in the attempt to get information on every mining company in Montana, it is possible that some companies have been overlooked. However, it is believed that this bulletin contains the names of most of the operating com- panies of the State, together with some general information on each company, and that the bulletin will serve as a valuable reference book for those interested in the mining industry. This bulletin is supple- mentary to a report on the various mining districts of Montana which is now being prepared by the Geological Department of the State Bureau of Mines and Metallurgy. —4— DIRECTORY OF MONTANA OPERATING METAL MINES ALICE GOLD AND SILVER MINING CO. Butte. Location: Summit Valley Mining District, Silver Bow County. Officers: Pres., John D. Ryan; Secy-Treas., D. B. Hennessy, 42 Broadway, New York, N. -

In the Shadow of the Big Stack: Black Eagle

In The Shadow of the Big Stack: Black Eagle In The Shadow of the Big Stack: Black Eagle. Martin, 384, 456, & Mildred (Amy) Black Eagle History Book Committee. Lillegard, 30-31, 310, 441, 479-482, 484, 511, 567, 575 Mary Lou, 31 ACM See Anaconda Copper Mining Co. Richard (Dick) & Lynette, 31 ADAMS Roland, 30, 429 David, 55 Ruth, 31 Donald & Delores Benedetti, 55 William, 31 Dr., 234, 236 AMERICAN SMELTING & REFINING Prohibition Federal Agent, 459 COMPANY OF GREAT FALLS Karen, 55 [aka old Silver Smelter], 8 AFRICA ANACONDA COPPER MINING CO., 6-22 Emigrants from Orange Free State, 197 Anaconda Zinc Plant, 22 ALAIR Black Smith Shop, 568 Harry, 578 Bowling Alley, 33 ALBANAS Cadmium Plant, 11 Mr., 478 Change Houses, 9 ALBERTINI Church, 474 Cheryl, 421 Copper Commando, 412 Dick, 455 Electrolytic Copper Refinery, 9-10 ALBRIGHT Employees Club, 14, 42 Kay, 375-377 Furnace Refinery, 9-10 ALDEN Great Falls Reduction Dept., 7 Janell, 73 History of, 511 Jody, 73 Klepetico Boarding House, 12 Wayne & Jo Anne Corr, 73 Laboratory, 9 ALINE Leaching Division, 11 Clotilda (Tillie), 214 Little Church, 13, 474 Enrico, 25, 269 Roasting Furnaces, 11 Gertrude, 267, 269 Rolling Mills, 9-10 Henry, 214 Safety Dept., 12, 221 Henry & Annie, 269 Shops, 9 Henry V., 214, 489 Smelter Hill Residential Area, 12-13, 64 Joe, 197, 331, 408 Smelter Stack, 22, 582 Sam, 214 Strikes, 14 ALLISON Tramming System, 11-12 Tex, 500 Unions and Strikes, 22 ALLAN Wire & Cable Plant, 8+, 36 Ada, 91 Wire Mill, 8+, 22 George & Veda, 91 Zinc Plant, 9-11 Jim & Kay Sanders Aragon, 91 ANDERSON ALLEN Alden K. -

ACM Smelter Residential Soil Health Consultation

Health Consultation Exposure to Lead and Arsenic in Surface Soil, Black Eagle Community ANACONDA COPPER MINING COMPANY SMELTER AND REFINERY SITE GREAT FALLS, CASCADE COUNTY, MONTANA EPA FACILITY ID: MTD093291599 SEPTEMBER 15, 2016 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Division of Community Health Investigations Atlanta, Georgia 30333 Health Consultation: A Note of Explanation A health consultation is a verbal or written response from ATSDR or ATSDR’s Cooperative Agreement Partners to a specific request for information about health risks related to a specific site, a chemical release, or the presence of hazardous material. In order to prevent or mitigate exposures, a consultation may lead to specific actions, such as restricting use of or replacing water supplies; intensifying environmental sampling; restricting site access; or removing the contaminated material. In addition, consultations may recommend additional public health actions, such as conducting health surveillance activities to evaluate exposure or trends in adverse health outcomes; conducting biological indicators of exposure studies to assess exposure; and providing health education for health care providers and community members. This concludes the health consultation process for this site, unless additional information is obtained by ATSDR or ATSDR’s Cooperative Agreement Partner which, in the Agency’s opinion, indicates a need to revise or append the conclusions previously issued. You May Contact ATSDR Toll Free at 1-800-CDC-INFO or Visit our Home Page at: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov HEALTH CONSULTATION Exposure to Lead and Arsenic in Surface Soil, Black Eagle Community ANACONDA COPPER MINING COMPANY SMELTER AND REFINERY SITE GREAT FALLS, CASCADE COUNTY, MONTANA EPA FACILITY ID: MTD093291599 Prepared By: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Division of Community Health Investigations Western Branch Table of Contents 1. -

Health Consultation

Health Consultation Evaluation of Residential Soil Arsenic Action Level ANACONDA CO. SMELTER NPL SITE ANACONDA, DEER LODGE COUNTY, MONTANA EPA FACILITY ID: MTD093291656 OCTOBER 19, 2007 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Division of Health Assessment and Consultation Atlanta, Georgia 30333 Health Consultation: A Note of Explanation An ATSDR health consultation is a verbal or written response from ATSDR to a specific request for information about health risks related to a specific site, a chemical release, or the presence of hazardous material. In order to prevent or mitigate exposures, a consultation may lead to specific actions, such as restricting use of or replacing water supplies; intensifying environmental sampling; restricting site access; or removing the contaminated material. In addition, consultations may recommend additional public health actions, such as conducting health surveillance activities to evaluate exposure or trends in adverse health outcomes; conducting biological indicators of exposure studies to assess exposure; and providing health education for health care providers and community members. This concludes the health consultation process for this site, unless additional information is obtained by ATSDR which, in the Agency’s opinion, indicates a need to revise or append the conclusions previously issued. You May Contact ATSDR TOLL FREE at 1-800-CDC-INFO or Visit our Home Page at: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov HEALTH CONSULTATION Evaluation of Residential Soil Arsenic Action Level ANACONDA CO. SMELTER NPL SITE ANACONDA, DEER LODGE COUNTY, MONTANA EPA FACILITY ID: MTD093291656 Prepared By: US Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry Division of Health Assessment and Consultation Atlanta, Georgia 30333 Anaconda Co. -

Miners, Managers, and Machines : Industrial Accidents And

Miners, managers, and machines : industrial accidents and occupational disease in the Butte underground, 1880-1920 by Brian Lee Shovers A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Montana State University © Copyright by Brian Lee Shovers (1987) Abstract: Between 1880 and 1920 Butte, Montana achieved world-class mining status for its copper production. At the same time, thousands of men succumbed to industrial accidents and contracted occupational disease in the Butte underground, making Butte mining significantly more dangerous than other industrial occupations of that era. Three major factors affected working conditions and worker safety in Butte: new mining technologies, corporate management, and worker attitude. The introduction of new mining technologies and corporate mine ownership after 1900 combined to create a sometimes dangerous dynamic between the miner and the work place in Butte. While technological advances in hoisting, tramming, lighting and ventilation generally improved underground working conditions, other technological adaptations such as the machine drill, increased the hazard of respiratory disease. In the end, the operational efficiencies associated with the new technologies could not alleviate the difficult problems of managing and supervising a highly independent, transient, and often inexperienced work force. With the beginning of the twentieth century and the consolidation of most of the major Butte mines under the corporate entity of Amalgamated Copper Company (later the Anaconda Copper Mining Company), conflict between worker and management above ground increased. At issue were wages, conditions, and a corporate reluctance to accept responsibility for occupational hazards. The new atmosphere of mistrust between miners and their supervisors provoked a defiant attitude towards the work place by workers which increased the potential for industrial accidents. -

![Hamilton, a Legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An Historical Pageant- Drama of Hamilton, Mont.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4511/hamilton-a-legacy-for-the-bitterroot-valley-an-historical-pageant-drama-of-hamilton-mont-1044511.webp)

Hamilton, a Legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An Historical Pageant- Drama of Hamilton, Mont.]

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1959 Hamilton, a legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An historical pageant- drama of Hamilton, Mont.] Donald William Butler The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Butler, Donald William, "Hamilton, a legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An historical pageant-drama of Hamilton, Mont.]" (1959). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2505. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2505 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HAMILTON A LEGACY FOR THE BITTERROOT VALLEY by DONALD WILLIAM BUTLER B.A. Montana State University, 1949 Presented in partial f-ulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1959 Approved by; / t*-v« ^—— Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School AUG 1 7 1959 Date UMI Number: EP34131 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT UMI EP34131 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. -

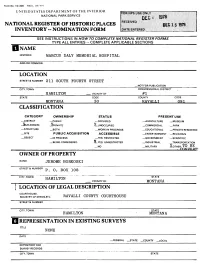

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE til NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN //OW 7~O COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC MARCUS DALY MEMORIAL HOSPITAL AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER 211 SOUTH FOURTH STREET —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT HAMILTON __.VICINITY OF #1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE MONTANA 30 RAVALLI 081 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _XuiLDING(S) _?PRIVATE X_UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY X.OTHER:TO BE OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME JEROME BORKOSKI STREETS, NUMBER p> Q> g^ ^ C.TY.TOWN HAMILTON STATE __ VICINITY OF MONTANA i LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. RAVALLI COUNTY COURTHOUSE STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE HAMILTON MONTANA REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS NONE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE _COUNTY __LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED X.UNALTERED X ORIGINAL SITE —RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Marcus Daly Hospital is one of the most impressive structures in the entire Bitterroot Valley. Construction on the structure, considered to b( the most fireproof possible, began in August, 1930. The design was pre pared by H. E. Kirkemo, architect, of Missoula, Montana. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: The Henge _________________________________________________ Other names/site number: N/A______________________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: N/A_________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 3600 La Joya Road__________________________________________ City or town: Roswell State: New Mexico County: Chaves Not For Publication: Vicinity: X ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register