Adolph Lewisohn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German North Sea Ports' Absorption Into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914

From Unification to Integration: The German North Sea Ports' absorption into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914 Henning Kuhlmann Submitted for the award of Master of Philosophy in History Cardiff University 2016 Summary This thesis concentrates on the economic integration of three principal German North Sea ports – Emden, Bremen and Hamburg – into the Bismarckian nation- state. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Emden, Hamburg and Bremen handled a major share of the German Empire’s total overseas trade. However, at the time of the foundation of the Kaiserreich, the cities’ roles within the Empire and the new German nation-state were not yet fully defined. Initially, Hamburg and Bremen insisted upon their traditional role as independent city-states and remained outside the Empire’s customs union. Emden, meanwhile, had welcomed outright annexation by Prussia in 1866. After centuries of economic stagnation, the city had great difficulties competing with Hamburg and Bremen and was hoping for Prussian support. This thesis examines how it was possible to integrate these port cities on an economic and on an underlying level of civic mentalities and local identities. Existing studies have often overlooked the importance that Bismarck attributed to the cultural or indeed the ideological re-alignment of Hamburg and Bremen. Therefore, this study will look at the way the people of Hamburg and Bremen traditionally defined their (liberal) identity and the way this changed during the 1870s and 1880s. It will also investigate the role of the acquisition of colonies during the process of Hamburg and Bremen’s accession. In Hamburg in particular, the agreement to join the customs union had a significant impact on the merchants’ stance on colonialism. -

Analysis of Timber Depredations in Montana to 1900

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1967 Analysis of timber depredations in Montana to 1900 Edward Bernie Butcher The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Butcher, Edward Bernie, "Analysis of timber depredations in Montana to 1900" (1967). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4709. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4709 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / 7y AN ANALYSIS OF TIMBER DEPREDATIONS IN MONTANA TO 1900 by Edward Bernie Butcher B. S. Eastern Montana College, 1965 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1967 Approved by: (fhe&d j Chairman, Board of Examiners Deaf, Graduate School JU N 1 9 1967 Date UMI Number: EP40173 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP40173 Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Clark and Daly - a Personality Analysis

The topper King?: Clark and Daly - A Personality Analysis A Thesis Presented to the Department of History, Carroll College, In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors By Michael D. Walsh * \ March 1975 CORETTE LIBRARY CARROI I mi I cr.c 5962 00082 610 CARROLL COLLEGE LIBRARY HELENA, MONTANA 596QH SIGNATURE PAGE This thesis for honors recognition has been approved for the Department of History. 7 rf7ir ....... .................7 ' Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For assistance in my research I wish to thank the staff of the Montana Historical Society Library. I would like to thank my mother who typed this paper and my father who provided the copies. My thanks to Cynthia Rubel and Michael Shields who served as proof readers. I am also grateful to Reverend Eugene Peoples,Ph.D., and Dr. William Lang who read this thesis and offered help ful suggestions. Finally, my thanks to Reverend William Greytak,Ph.D, my director, for h1s criticism, guidance and encouragement which helped me to complete this work. CONTENTS Chapter 1. Their Contemporaries.................................... 1 Chapter 2. History’s Viewpoint ..................................... 13 Chapter 3. Correspondence and Personal Reflections . .................... ....... 24 Bibliography 32 CHAPTER 1 Their Contemporaries In 1809 the territory of Montana was admitted to the Union as the forty-first state, With this act Montana now had to concern herself with the elections of public officials and the selection of a location for the capital. For the next twelve years these political issues would provide the battleground for two men, fighting for supremacy in the state; two men having contributed considerably to the development of Montana (prior to 1889) would now subject her to twelve years of political corruption, William Andrew Clark, a migrant from Pennsylvania, craved the power which would be his if he were to become the senator from Montana. -

![Hamilton, a Legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An Historical Pageant- Drama of Hamilton, Mont.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4511/hamilton-a-legacy-for-the-bitterroot-valley-an-historical-pageant-drama-of-hamilton-mont-1044511.webp)

Hamilton, a Legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An Historical Pageant- Drama of Hamilton, Mont.]

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1959 Hamilton, a legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An historical pageant- drama of Hamilton, Mont.] Donald William Butler The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Butler, Donald William, "Hamilton, a legacy for the Bitterroot Valley. [An historical pageant-drama of Hamilton, Mont.]" (1959). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2505. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2505 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HAMILTON A LEGACY FOR THE BITTERROOT VALLEY by DONALD WILLIAM BUTLER B.A. Montana State University, 1949 Presented in partial f-ulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1959 Approved by; / t*-v« ^—— Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School AUG 1 7 1959 Date UMI Number: EP34131 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT UMI EP34131 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. -

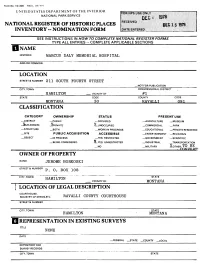

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE til NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN //OW 7~O COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC MARCUS DALY MEMORIAL HOSPITAL AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER 211 SOUTH FOURTH STREET —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT HAMILTON __.VICINITY OF #1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE MONTANA 30 RAVALLI 081 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _XuiLDING(S) _?PRIVATE X_UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY X.OTHER:TO BE OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME JEROME BORKOSKI STREETS, NUMBER p> Q> g^ ^ C.TY.TOWN HAMILTON STATE __ VICINITY OF MONTANA i LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. RAVALLI COUNTY COURTHOUSE STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE HAMILTON MONTANA REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS NONE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE _COUNTY __LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED X.UNALTERED X ORIGINAL SITE —RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Marcus Daly Hospital is one of the most impressive structures in the entire Bitterroot Valley. Construction on the structure, considered to b( the most fireproof possible, began in August, 1930. The design was pre pared by H. E. Kirkemo, architect, of Missoula, Montana. -

100Years the Antiquities Act 1906-2006 the National Historic Preservation Act 1966-2006 of Preservation

100years the antiquities act 1906-2006 the national historic preservation act 1966-2006 of preservation photographs by jack e. boucher and jet lowe PillarOF PRESERVATION celebrating four decades of the national historic preservation act “I was dismayed to learn from reading this report that almost half of the 12,000 structures list- ed in the Historic American Buildings Survey of the National Park Service have already been destroyed,” writes Lady Bird Johnson in the foreword to With Heritage So Rich, the call to arms pub- lished in tandem with the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. Urban renewal seemed unstoppable in the early ’60s. Pennsylvania Avenue, deemed dowdy by President Kennedy during his inaugural parade, was slated for a makeover by modernist architects. “The champions of modern architecture seldom missed an opportunity to ridicule the past,” historian Richard Longstreth wrote in these pages a few years ago, reassessing the era. “Buildings and cities created since the rise of industrial- ization were charged with having nearly ruined the planet. The legacy of one’s parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents was not only visually meaningless and degenerate, but socially and spiritually repres- sive as well.” Against this tide, a generation rose up, giving birth to a populist movement. Here, Common Ground salutes what was saved, and what was lost. Right: The National Archives, along Pennsylvania Avenue. 28 COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2006 COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2006 29 30 COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2006 FAR LEFT AND BELOW JET LOWE/NPS/HAER, JACK E. BOUCHER/NPS/HAER FAR The National Historic Preservation Act—embracing the full breadth of sites integral to the nation’s story—reflects a dynamic vision of the past and the ingredients that make it matter. -

Shipping Made in Hamburg

Shipping made in Hamburg The history of the Hapag-Lloyd AG THE HISTORY OF THE HAPAG-LLOYD AG Historical Context By the middle of the 19th Century the industrial revolution has caused the disap- pearance of many crafts in Europe, fewer and fewer workers are now required. In a first process of globalization transport links are developing at great speed. For the first time, railways are enabling even ordinary citizens to move their place of residen- ce, while the first steamships are being tested in overseas trades. A great wave of emigration to the United States is just starting. “Speak up! Why are you moving away?” asks the poet Ferdinand Freiligrath in the ballad “The emigrants” that became something of a hymn for a German national mo- vement. The answer is simple: Because they can no longer stand life at home. Until 1918, stress and political repression cause millions of Europeans, among them many Germans, especially, to make off for the New World to look for new opportunities, a new life. Germany is splintered into backward princedoms under absolute rule. Mass poverty prevails and the lower orders are emigrating in swarms. That suits the rulers only too well, since a ticket to America produces a solution to all social problems. Any troublemaker can be sent across the big pond. The residents of entire almshouses are collectively despatched on voyage. New York is soon complaining about hordes of German beggars. The dangers of emigration are just as unlimited as the hoped-for opportunities in the USA. Most of the emigrants are literally without any experience, have never left their place of birth, and before the paradise they dream of, comes a hell. -

Gemze De Lappe Career Highlights

DATE END (if avail) LOCATION SHOW/EVENT ROLE (if applicable) COMPANY NOTES 1922/02/28 Portsmouth, VA Born Gemze Mary de Lappe BORN Performed during the summer - would do ballets during intermission of productions of 1931/00/00 1939/00/00 Lewisohn Stadium, NY Michael Fokine Ballet dancer Michael Folkine recent Broadway shows. 1941/11/05 1941/11/11 New York La Vie Parisienne Ballet 44th St. New Opera Company 1943/11/15 1945/01/00 Chicago Oklahoma! Aggie National Tour with John Raitt Premiere at the old Metropolitan Opera House - Jerome Robbins choreographed Fancy Free, which was later developed into 1944/04/18 New York Fancy Free [Jerome Robbins] dancer Ballet Theatre On the Town 1945/01/08 St. Louis Oklahoma! Aggie 1945/01/29 1945/02/10 Milwaukee Oklahoma! Aggie 1945/03/05 Detroit Oklahoma! Aggie 1945/04/09 Pittsburgh Oklahoma! Aggie 1945/06/18 Philadelphia Oklahoma! Aggie National Tour 1946/01/22 Minneapolis Oklahoma! Ellen/Dream Laurey National Tour Ellen/Dream Laurey 1946/08/19 New York Oklahoma! (replacement) St. James 1947/04/30 London Oklahoma! Dream Laurey Theatre Royal Drury Lane with Howard Keel Melbourne, Victoria, Recreated 1949/02/19 Australia Oklahoma! Choreography Australia Premiere 1951/03/29 New York The King and I King Simon of Legree St. James 1951/10/01 Philadelphia Paint Your Wagon Yvonne Pre-Broadway Tryout 1951/10/08 Boston Paint Your Wagon Yvonne Pre-Broadway Tryout 1951/11/12 1952/07/19 New York Paint Your Wagon Yvonne Shubert The Donaldson Awards were a set of theatre awards established in 1944 by the drama critic Robert Francis in honor of W. -

Factbook201112.Pdf

New York Philharmonic Contents 2 2011–12 Season: The Big Picture Stats Alan Gilbert Conducts Artistic Partners Onstage Guests Principals, Center Stage 24 Learning Around the Globe For Kids and Teens Stand-Outs Lectures and Discussions Media Leonard Bernstein Scholar-in-Residence Online 20 The Players For Schools 22 Leadership 26 Premieres and Commissions Music Director 2011–12 Season Chairman Notable 21st Century President and Executive Director Notable 20th Century Notable 19th Century 28 The Legacy The Story Memorable Moments Former Music Directors and Advisors 32 Behind the Scenes Archives Volunteer Council nyphil.org The Philharmonic-Symphony Ticket Information Society of New York, Inc. Online: nyphil.org By phone: (212) 875 - 5656 Alan Gilbert, Music Director, In person: Avery Fisher Hall Box Office The partnership between the New York Philharmonic and The Yoko Nagae Ceschina Chair For group sales: (212) 875 - 5672 Credit Suisse — the Orchestra’s exclusive Global Sponsor Gary W. Parr, Chairman Accessibility Information: since 2007 — has led to inspiring performances both at Zarin Mehta, President (212) 875 - 5380 home and abroad through acclaimed tours across the and Executive Director United States, Europe, and Asia. In the 2011–12 season, Avery Fisher Hall Box Office Hours Credit Suisse’s dynamic support of the Orchestra’s Avery Fisher Hall Opens 10:00 a.m., Monday through programs helps to forge the Philharmonic’s central role in 10 Lincoln Center Plaza Saturday, noon on Sunday. the cultural life of New York, and to share Music Director New York, NY 10023 -6970 On performance evenings Alan Gilbert’s vision with the world. -

The Concerts at Lewisohn Stadium, 1922-1964

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2009 Music for the (American) People: The Concerts at Lewisohn Stadium, 1922-1964 Jonathan Stern The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2239 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MUSIC FOR THE (AMERICAN) PEOPLE: THE CONCERTS AT LEWISOHN STADIUM, 1922-1964 by JONATHAN STERN VOLUME I A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2009 ©2009 JONATHAN STERN All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Professor Ora Frishberg Saloman Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor David Olan Date Executive Officer Professor Stephen Blum Professor John Graziano Professor Bruce Saylor Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract MUSIC FOR THE (AMERICAN) PEOPLE: THE LEWISOHN STADIUM CONCERTS, 1922-1964 by Jonathan Stern Adviser: Professor John Graziano Not long after construction began for an athletic field at City College of New York, school officials conceived the idea of that same field serving as an outdoor concert hall during the summer months. The result, Lewisohn Stadium, named after its principal benefactor, Adolph Lewisohn, and modeled much along the lines of an ancient Roman coliseum, became that and much more. -

Genealogy of the Kobernuss Families of Alt-Gaarz Mecklenburg

Genealogy and Immigration History of the Kobernuss Families of Alt-Gaarz, Mecklenburg, Germany 1752-2010 The Hammonia Immigration ship of Carl and Sophie Kobernus November 14, 1873 “As you look toward the future, always remember the treasures of our Past. Every generation stands on the shoulders of the generation that came before. Jealously guard the values and principles of our heritage. They did not come easy.” -Ronald Reagan- Author: George Martin Kobernus, Colonel USAF (Ret.) Revision 7, Publish date: 1 January 2013 Destroy all previous versions Table of Contents DEDICATION ............................................................................................ 4 FORWARD ................................................................................................ 5 CHAPTER 1: Overview ............................................................................ 7 Synopsis ............................................................................................. 7 Background ........................................................................................ 7 A Short History And Geography Lesson ............................................. 7 Early Likely Ancestors ........................................................................ 9 Distribution Of Families In Germany ................................................... 9 Possible Origins Of The Names ....................................................... 10 CHAPTER 2: The Challenges of Family Research .............................. 12 Naming Customs ............................................................................. -

Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2020 Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star Caleb Taylor Boyd Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Boyd, Caleb Taylor, "Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star" (2020). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2169. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/2169 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Todd Decker, Chair Ben Duane Howard Pollack Alexander Stefaniak Gaylyn Studlar Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star by Caleb T. Boyd A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 St. Louis, Missouri © 2020, Caleb T. Boyd Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................