Cuba and Venezuela

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rhetoric of Fidel Castro Brent C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 From the mountains to the podium: the rhetoric of Fidel Castro Brent C. Kice Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kice, Brent C., "From the mountains to the podium: the rhetoric of Fidel Castro" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1766. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. FROM THE MOUNTAINS TO THE PODIUM: THE RHETORIC OF FIDEL CASTRO A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by Brent C. Kice B.A., Loyola University New Orleans, 2002 M.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2004 December 2008 DEDICATION To my wife, Dori, for providing me strength during this arduous journey ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Andy King for all of his guidance, and especially his impeccable impersonations. I also wish to thank Stephanie Grey, Ruth Bowman, Renee Edwards, David Lindenfeld, and Mary Brody for their suggestions during this project. I am so thankful for the care and advice given to me by Loretta Pecchioni. -

Societies of the World 15: the Cuban Revolution, 1956-1971

Societies of the World 15 Societies of the World 15 The Cuban Revolution, 1956-1971: A Self-Debate Jorge I. Domínguez Office Hours: MW, 11:15-12:00 Fall term 2011 or by appointment MWF at 10, plus section WCFIA, 1737 Cambridge St. Course web site: Office #216, tel. 495-5982 http://isites.harvard.edu/k80129 email: [email protected] WEEK 1 W Aug 31 01.Introduction F Sep 2 Section in lecture hall: Why might revolutions occur? Jaime Suchlicki, Cuba: From Columbus to Castro and Beyond (Fifth edition; Potomac Books, Inc., 2002 [or Brassey’s Fifth Edition, also 2002]), pp. 87-133. ISBN 978-1-5-7488436-4. Louis A. Pérez, Jr., Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution (Third edition; Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. xii-xiv, 210-236. ISBN 978-0-1-9517912-5. WEEK 2 (Weekly sections with Teaching Fellows begin meeting this week, times to be arranged.) M Sep 5 HOLIDAY W Sep 7 02.The Unnecessary Revolution F Sep 9 03.Modernization and Revolution [Sourcebook] Cuban Economic Research Project, A Study on Cuba (University of Miami Press, 1965), pp. 409-411, 619-622 [Sourcebook] Jorge J. Domínguez, “Some Memories (Some Confidential)” (typescript, 1995), 9 pp. [Sourcebook] James O’Connor, The Origins of Socialism in Cuba (Cornell University Press, 1970), pp, 1-33, 37-54 1 Societies of the World 15 [Sourcebook] Edward Gonzalez, Cuba under Castro: The Limits of Charisma (Houghton Mifflin, 1974), pp. 13-110 [Online] Morris H. Morley, “The U.S. Imperial State in Cuba 1952-1958: Policy Making and Capitalist Interests, Journal of Latin American Studies 14, no. -

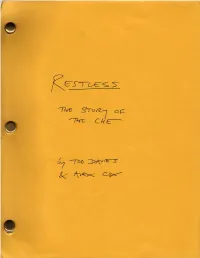

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

¡Patria O Muerte!: José Martí, Fidel Castro, and the Path to Cuban Communism

¡Patria o Muerte!: José Martí, Fidel Castro, and the Path to Cuban Communism A Thesis By: Brett Stokes Department: History To be defended: April 10, 2013 Primary Thesis Advisor: Robert Ferry, History Department Honors Council Representative: John Willis, History Outside Reader: Andy Baker, Political Science 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank all those who assisted me in the process of writing this thesis: Professor Robert Ferry, for taking the time to help me with my writing and offer me valuable criticism for the duration of my project. Professor John Willis, for assisting me in developing my topic and for showing me the fundamentals of undertaking such a project. My parents, Bruce and Sharon Stokes, for reading and critiquing my writing along the way. My friends and loved-ones, who have offered me their support and continued encouragement in completing my thesis. 2 Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 CHAPTER ONE: Martí and the Historical Roots of the Cuban Revolution, 1895-1952 12 CHAPTER TWO: Revolution, Falling Out, and Change in Course, 1952-1959 34 CHAPTER THREE: Consolidating a Martían Communism, 1959-1962 71 Concluding Remarks 88 Bibliography 91 3 Abstract What prompted Fidel Castro to choose a communist path for the Cuban Revolution? There is no way to know for sure what the cause of Castro’s decision to state the Marxist nature of the revolution was. However, we can know the factors that contributed to this ideological shift. This thesis will argue that the decision to radicalize the revolution and develop a relationship with the Cuban communists was the only logical choice available to Castro in order to fulfill Jose Marti’s, Cuba’s nationalist hero, vision of an independent Cuba. -

Review of Julia E. Sweig's Inside the Cuban Revolution

Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground. By Julia E. Sweig. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002. xx, 255 pp. List of illustrations, acknowledgments, abbre- viations, about the research, notes, bibliography, index. $29.95 cloth.) Cuban studies, like former Soviet studies, is a bipolar field. This is partly because the Castro regime is a zealous guardian of its revolutionary image as it plays into current politics. As a result, the Cuban government carefully screens the writings and political ide- ology of all scholars allowed access to official documents. Julia Sweig arrived in Havana in 1995 with the right credentials. Her book preface expresses gratitude to various Cuban government officials and friends comprising a who's who of activists against the U.S. embargo on Cuba during the last three decades. This work, a revision of the author's Ph.D. dissertation, ana- lyzes the struggle of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement (M-26-7) against the Fulgencio Batista dictatorship from November 1956 to July 1958. Sweig recounts how the M-26-7 urban underground, which provided the recruits, weapons, and funds for the guerrillas in the mountains, initially had a leading role in decision making, until Castro imposed absolute control over the movement. The "heart and soul" of this book is based on nearly one thousand his- toric documents from the Cuban Council of State Archives, previ- ously unavailable to scholars. Yet, the author admits that there is "still-classified" material that she was unable to examine, despite her repeated requests, especially the correspondence between Fidel Castro and former president Carlos Prio, and the Celia Sánchez collection. -

Research and Reference Service

LBJ Library, NSF, box 21, Country, Latin America, Cuba, Chronology > ? Research and Reference Service CHRONOLOGY OF CUBAN EVENTS, 1963 R-167-64 October 23, 1964 This is a research report, not a statement of Agency policy w . - . .- COPY LBJ UBRARY CHRONOLOGY OF CUBAN EVENTS, 1963 The following were selected as the more significant developments in Cuban affairs during 1963. January 1 The Soviet news agency Novosti established an office in Havana. In a speech on the fourth anniversary of the Revolution, Fidel Castro reiterated the D-t Cuban ~olicvthat holds UD the revolution as a model for the Hemisphere. "We ape examples for the brother peoples of Latin America.... If the workers and people of Latin America had weapons as our people do, we would see what would happen.... We have the great historic task of bringfng this revolution forward, of serving as an example for the revolutionaries of Latin America- and within the socialist camp, which is and always will be our family." 7 The first TU-114 (~eroflot)turboprop aircraft on the new Moscow-Havana schedule arrived in Havana. 8 The Castro Government, r;-k~;..~:L;cd 62 local medical insurance clinics, assigning them to the Ministry of Public Health and closed 38 others for "lack of adequatet1 facilities. 8 A top-level Soviet military mission departed after spending several days in Cuba. Prensa Latina reported that the mission inspected a number of Soviet installations and conferred with Russian military leaders sta- tioned on the island. 11 The Congress of Women of the Americas was inaugurated in Havana with approximately 500 participants from most Latin American countries and observers from ~o&unistbloc countries. -

Cultura E Revolução Em Cuba Nas Memórias Literárias De Dois Intelectuais Exilados, Carlos Franqui E Guillermo Cabrera Infante (1951-1968)

BARTHON FAVATTO SUZANO JÚNIOR ENTRE O DOCE E O AMARGO: cultura e revolução em Cuba nas memórias literárias de dois intelectuais exilados, Carlos Franqui e Guillermo Cabrera Infante (1951-1968). ASSIS 2012 BARTHON FAVATTO SUZANO JÚNIOR ENTRE O DOCE E O AMARGO: cultura e revolução em Cuba nas memórias literárias de dois intelectuais exilados, Carlos Franqui e Guillermo Cabrera Infante (1951-1968). Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para obtenção do título de Mestre em História (Área de Conhecimento: História e Sociedade.) Orientador: Prof. Dr. Carlos Alberto Sampaio Barbosa. ASSIS 2012 Catalogação da Publicação Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Biblioteca da F.C.L. – Assis – UNESP Favatto Júnior, Barthon F272e Entre o doce e o amargo: cultura e revolução em Cuba nas memórias literárias de dois intelectuais exilados, Carlos Franqui e Guillermo Cabrera Infante (1951-1968) / Barthon Favatto Suzano Júnior. Assis, 2012 197 f. Dissertação de Mestrado – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – Universidade Estadual Paulista. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Carlos Alberto Sampaio Barbosa 1. Cuba – História – Revolução, 1959. 2. Intelectuais e política. 3. Exílio. 4. Franqui, Carlos, 1921-2010. 5. Cabrera Infante, Guillermo, 1929-2005. I. Título. CDD 972.91064 AGRADECIMENTOS A realização de um trabalho desta envergadura não constitui tarefa fácil, tampouco é produto exclusivo do labor silencioso e solitário do pesquisador. Por detrás da capa que abre esta dissertação há inúmeros agentes históricos que imprimiram nas páginas que seguem suas importantes, peremptórias e indeléveis contribuições. Primeiramente, agradeço ao Prof. Dr. Carlos Alberto Sampaio Barbosa, amigo e orientador nesta, em passadas e em futuras jornadas, que como um maestro soube conduzir com rigor e sensibilidade intelectual esta sinfonia. -

A Strategic Flip-Flop in the Caribbean 63

Hoover Press : EPP 100 DP5 HPEP000100 23-02-00 rev1 page 62 62 William Ratliff and Roger Fontaine U.S. interference in Cuban affairs. In effect it gives him a veto over U.S. policy. Therefore the path of giving U.S. politicians a “way out” won’t in fact work because Castro will twist it to his interests. Better to just do it unilaterally on our own timetable. For the time being it appears U.S. policy will remain reactive—to Castro and to Cuban American pressure groups—irrespective of the interests of Americans and Cubans as a whole. Like parrots, all presi- dential hopefuls in the 2000 presidential elections propose varying ver- sions of the current failed policy. We have made much here of the negative role of the Cuba lobby, but we close by reiterating that their advocacy has not usually been different in kind from that of other pressure groups, simply much more effective. The buck falls on the politicians who cannot see the need for, or are afraid to support, a new policy for the post–cold war world. Notes 1. This presentation of the issues is based on but goes far beyond written testimony—“U.S. Cuban Policy—a New Strategy for the Future”— which the authors presented to the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Com- mittee on 24 May 1995. We have long advocated this change, beginning with William Ratliff, “The Big Cuba Myth,” San Jose Mercury News,15 December 1992, and William Ratliff and Roger Fontaine, “Foil Castro,” Washington Post, 30 June 1993. -

Fidel Castro and Revolutionary Masculinity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies Hispanic Studies 2012 Deconstructing an Icon: Fidel Castro and Revolutionary Masculinity Krissie Butler University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Butler, Krissie, "Deconstructing an Icon: Fidel Castro and Revolutionary Masculinity" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies. 10. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/hisp_etds/10 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of my work. -

Modernidad Y Vanguardia: Rutas De Intercambio Entre España Y Latinoamérica (1920-1970)

Modernidad y vanguardia: rutas de intercambio entre España y Latinoamérica (1920-1970) Modernidad y vanguardia: rutas de intercambio entre España y Latinoamérica (1920-1970) Edición coordinada por PAULA BARREIRO LÓPEZ y FABIOLA MARTÍNEZ RODRÍGUEZ Prólogo Un fenómeno imprevisto de nuestra era global, cuando parecía que se había clau- surado la capacidad del mito moderno para detonar y articular discursos sobre el tiempo, es la urgencia sentida desde posiciones múltiples y diversas de narrar de nuevo; de narrar situadamente la modernidad propia dentro de un nuevo mapa de relaciones. Si algo tenían en común las historiografías de la vanguardia en los países de Amé- rica Latina y España era que pendulaban entre la lógica centrípeta de la construcción nacional y la centrífuga de la dependencia respecto los focos internacionales, dentro de una estructura netamente colonial. Las pulsiones narrativas que pretendía convocar el congreso Encuentros transatlánticos: discursos vanguardistas en España y Latinoamé- rica —y que recoge el presente volumen— van a contrapelo de ambas lógicas. Mediante una pluralidad de casos de estudio, desvelan la inadecuación tanto del marco nacional, como de la polaridad centro-periferia a la hora de dar cuenta de la riqueza y la comple- jidad de los proyectos y procesos de vanguardia en nuestros contextos. El fin de esta convocatoria no era simplemente proponer un nuevo paradigma “distribuido” que sustituyera los modelos “radiales” de la modernidad; uno que fuera más acorde con los nuevos equilibrios de poder y los múltiples focos de la globalización. Tampoco se intentaba reivindicar por enésima vez un escenario iberoamericano cuyas gastadas retóricas, propias de los periodos más oscuros de nuestro pasado reciente, no hacían sino confirmar nuestra situación como provincia de la modernidad. -

O Desaparecimento Do Comandante Camilo Cienfuegos

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTÓRIA THAIS ROSALINA TURIAL BRITO ENTRE MEMÓRIAS, NARRATIVAS E ESQUECIMENTOS: O DESAPARECIMENTO DO COMANDANTE CAMILO CIENFUEGOS BRASÍLIA 2014 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTÓRIA ENTRE MEMÓRIAS, NARRATIVAS E ESQUECIMENTOS: O DESAPARECIMENTO DO COMANDANTE CAMILO CIENFUEGOS Monografia apresentada ao Departamento de História do Instituto de Ciências Humanas da Universidade de Brasília para a obtenção do grau de licenciado em História, sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. Jaime de Almeida. BRASÍLIA 2014 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTÓRIA ENTRE MEMÓRIAS, NARRATIVAS E ESQUECIMENTOS: O DESAPARECIMENTO DO COMANDANTE CAMILO CIENFUEGOS BANCA EXAMINADORA: ______________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Jaime de Almeida (Orientador) ______________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Francisco Fernando Monteoliva Doratioto ______________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Luiz Paulo Ferreira Nogueról ______________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Carlos Eduardo Vidigal (Suplente) Data da Defesa: 05 de dezembro de 2014 BRASÍLIA 2014 AGRADECIMENTOS Quero agradecer a todos aqueles que de alguma forma estiveram presentes no percurso desta pesquisa. Primeiramente, ao meu querido esposo Marcelo Brito pelo constante apoio aos meus mais ousados projetos acadêmicos. Ao orientador desta pesquisa e amigo, professor Jaime de Almeida, que me mostrou a beleza do que é ser um historiador. Com seu valor intelectual e a sua experiência investigativa me ajudou a levar este trabalho além do que foi pensado e com muita dedicação, acreditou neste projeto quando tudo indicava que seria um grande desafio. À professora Eleonora Zicari, que forneceu sugestões maravilhosas de referências bibliográficas que me permitiram construir meu arcabouço teórico-metodológico. Ao professor Giliard Prado, pela interlocução e apoio constante a esta pesquisa. -

Major American News Magazines and the Cuban Revolution| 1957--1971

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1972 Major American news magazines and the Cuban Revolution| 1957--1971 Joel Phillip Kleinman The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kleinman, Joel Phillip, "Major American news magazines and the Cuban Revolution| 1957--1971" (1972). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2900. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2900 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAJOR AMERICAN NEWS MAGAZINES AND THE CUBAN REVOLUTION; 1957-1971 By Joel P. Klelnman B.A., STATE UNIVERSITY OP NEW YORK AT BUFFALO, 1970 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1972 Approved by: JkùAAJtM. ) yéAWi/ Chairman, Board ^ Examiners Xy //( • Dea^rJ/Gradi^te^Schooj Date T77 UMI Number: EP36356 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT UMI EP36356 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012).