A Strategic Flip-Flop in the Caribbean 63

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuba After Castro Definitive Book by AEI Scholar Mark Falcoff Challenges Preconceptions

Media inquiries: Véronique Rodman 202.862.4871 ([email protected]) Orders: 800.343.4499 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: August 1, 2003 Cuba after Castro Definitive Book by AEI Scholar Mark Falcoff Challenges Preconceptions Since the collapse of the Soviet Union more than a decade ago, media attention on Cuba has focused on the controversy over lifting the U.S. trade embargo. Mark Falcoff’s new book, Cuba the Morning After: Confronting Castro’s Legacy (AEI Press, September 17, 2003) argues that this debate is largely irrelevant. The wreckage of Cuba after forty years of Castro’s rule is so profound that the country may never recover. According to Falcoff, lifting the U.S. embargo will be of negligible benefit to the country. Far more important are the formidable problems of Castro’s legacy: political repression, a failed economy, environmental degradation, and a permanently impoverished population with expecta- tions of free housing, free education, and free healthcare. Falcoff reminds us that Cuba’s economic downfall has been steep. In 1958, Cuba was in the top rank of most Latin American indices of development—urbanization, services, health, and literacy. Much of its prosperity was based on the favorable place reserved for its sugar harvest in the U.S. domestic market. Since then, the Cuban quota has been divided up among other countries, and sugar itself is no longer a particularly valuable commodity. Meanwhile, Cuba’s antiquated sugar industry is near collapse; last year Fidel Castro was forced to shut down almost half of the country’s mills. Today, like most Caribbean islands, Cuba survives on tourism and remittances from Cubans living abroad. -

The Rhetoric of Fidel Castro Brent C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 From the mountains to the podium: the rhetoric of Fidel Castro Brent C. Kice Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kice, Brent C., "From the mountains to the podium: the rhetoric of Fidel Castro" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1766. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. FROM THE MOUNTAINS TO THE PODIUM: THE RHETORIC OF FIDEL CASTRO A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by Brent C. Kice B.A., Loyola University New Orleans, 2002 M.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2004 December 2008 DEDICATION To my wife, Dori, for providing me strength during this arduous journey ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Andy King for all of his guidance, and especially his impeccable impersonations. I also wish to thank Stephanie Grey, Ruth Bowman, Renee Edwards, David Lindenfeld, and Mary Brody for their suggestions during this project. I am so thankful for the care and advice given to me by Loretta Pecchioni. -

Societies of the World 15: the Cuban Revolution, 1956-1971

Societies of the World 15 Societies of the World 15 The Cuban Revolution, 1956-1971: A Self-Debate Jorge I. Domínguez Office Hours: MW, 11:15-12:00 Fall term 2011 or by appointment MWF at 10, plus section WCFIA, 1737 Cambridge St. Course web site: Office #216, tel. 495-5982 http://isites.harvard.edu/k80129 email: [email protected] WEEK 1 W Aug 31 01.Introduction F Sep 2 Section in lecture hall: Why might revolutions occur? Jaime Suchlicki, Cuba: From Columbus to Castro and Beyond (Fifth edition; Potomac Books, Inc., 2002 [or Brassey’s Fifth Edition, also 2002]), pp. 87-133. ISBN 978-1-5-7488436-4. Louis A. Pérez, Jr., Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution (Third edition; Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. xii-xiv, 210-236. ISBN 978-0-1-9517912-5. WEEK 2 (Weekly sections with Teaching Fellows begin meeting this week, times to be arranged.) M Sep 5 HOLIDAY W Sep 7 02.The Unnecessary Revolution F Sep 9 03.Modernization and Revolution [Sourcebook] Cuban Economic Research Project, A Study on Cuba (University of Miami Press, 1965), pp. 409-411, 619-622 [Sourcebook] Jorge J. Domínguez, “Some Memories (Some Confidential)” (typescript, 1995), 9 pp. [Sourcebook] James O’Connor, The Origins of Socialism in Cuba (Cornell University Press, 1970), pp, 1-33, 37-54 1 Societies of the World 15 [Sourcebook] Edward Gonzalez, Cuba under Castro: The Limits of Charisma (Houghton Mifflin, 1974), pp. 13-110 [Online] Morris H. Morley, “The U.S. Imperial State in Cuba 1952-1958: Policy Making and Capitalist Interests, Journal of Latin American Studies 14, no. -

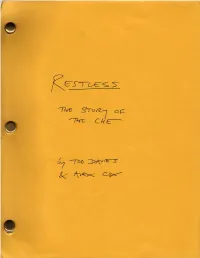

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Sino-Venezuelan Relations: Beyond Oil

Issues & Studies© 44, no. 3 (September 2008): 99-147. Sino-Venezuelan Relations: Beyond Oil JOSEPH Y. S. CHENG AND HUANGAO SHI Sino-Venezuelan relations have witnessed an unprecedented inti- macy since the beginning of Hugo Chávez's presidency in 1999. While scholars hold divergent views on the possible implications of the suddenly improved bilateral relationship, they have reached a basic consensus that oil has been the driving force. This article explores the underlying dy- namics of this relationship from the Chinese perspective. It argues that oil interest actually plays a rather limited role and will continue to remain an insignificant variable in Sino-Venezuelan ties in the foreseeable future. Despite the apparent closeness of the ties in recent years, the foundation forcontinued improvement in the future seems farfromsolid. Sino-Venezue- lan relations have caused serious concerns in the United States, which, for centuries, have seen Latin America as its sphere of influence. Although the neo-conservatives are worried about the deviant Chávez administration and a rising China, the chance of any direct U.S. intervention remains slim. Nevertheless, the China-U.S.-Venezuelan triangular relationship poses a JOSEPH Y. S. CHENG (鄭宇碩) is chair professor of political science and coordinator of the Contemporary China Research Project, City University of Hong Kong. He is the founding editor of the Hong Kong Journal of Social Sciences and The Journal of Comparative Asian Development. He has published widely on political development in China and Hong Kong, Chinese foreign policy, and local government in southern China. His e-mail address is <[email protected]>. -

Professor Alberto R. Coll Depaul University College of Law 25 East Jackson Boulevard Chicago, Illinois 60604

Professor Alberto R. Coll DePaul University College of Law 25 East Jackson Boulevard Chicago, Illinois 60604 [email protected] Office (312) 362-5663 Mobile (401) 474-0141 Professor of Law, DePaul University College of Law, Chicago (2005 - ) Director, European and Latin American Legal Studies Director, LLM International Law Program Director, Global Engagement Teaching and academic advisory responsibilities in the areas of public and private international law, international human rights, comparative law, international trade, U.S. Foreign Relations, and Latin America. Courses: Public International Law; International Protection of Human Rights; International Trade; Terrorism, the Constitution, and International Law; United States Foreign Relations Law; Comparative Law; European Human Rights Law; Human Rights in Latin America; Doing Business in Latin America; International Civil Litigation in United States Courts. Founder and director of De Paul – Universidad Pontificia Comillas (Madrid) Joint Degree program in International and European Business Law: De Paul students receive in three years’ time their JD and an LLM in International and European Business Law from Spain’s highest-ranked private law school and business school ranked #51 globally. Founder and director of highly successful study abroad and faculty-student exchange programs with the highest-ranked private law schools in Buenos Aires, Argentina and Madrid, Spain, and director of De Paul’s program in Costa Rica that engages law students in the workings of the Inter-American human rights system, including the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the Center for Justice and International Law. Working with the University of Havana Law School, established an annual, ABA- approved, week-long study program in Havana open to students from all U.S. -

The Independent Institute and Editor of Other Financial Institutions

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 4 wINTER 2010 Economic Troubles and the Growth of Government by Robert Higgs* he current recession to a head in late September 2008 proved to be the Tand, especially, the re- catalyst for an accelerated decline in real GDP and lated financial panic in the rise in the rate of unemployment. The so-called fall of 2008 have given rise credit crunch in the fall to an extraordinary surge in of 2008 prompted the the U.S. government’s size, Fed, the Treasury, and scope, and power. As I write, the Congress to take a the financial panic has subsided, but series of extraordinary the recession, already the longest actions in quick suc- since the 1930s, seems likely to con- cession. tinue for a long time. Even when it has In September 2008, passed, however, the government will the Federal Reserve Sys- certainly retain much tem (“the Fed”) took of the augmentation control of the insurance it has gained recently. giant American International Group Hence, this crisis will (AIG), and the Federal Housing Fi- prove to be the occasion nance Authority took over the huge for another episode of government-sponsored enterprises the ratchet effect in the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, secondary lending growth of government. institutions that held or insured more than half of According to the Na- the total value of U.S. residential mortgages. On tional Bureau of Eco- October 3, the president signed the Emergency nomic Research, the recession began early in Economic Stabilization Act, which, among other 2008, but the decline became severe only in the things, created the Troubled Assets Relief Program latter part of the year. -

¡Patria O Muerte!: José Martí, Fidel Castro, and the Path to Cuban Communism

¡Patria o Muerte!: José Martí, Fidel Castro, and the Path to Cuban Communism A Thesis By: Brett Stokes Department: History To be defended: April 10, 2013 Primary Thesis Advisor: Robert Ferry, History Department Honors Council Representative: John Willis, History Outside Reader: Andy Baker, Political Science 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank all those who assisted me in the process of writing this thesis: Professor Robert Ferry, for taking the time to help me with my writing and offer me valuable criticism for the duration of my project. Professor John Willis, for assisting me in developing my topic and for showing me the fundamentals of undertaking such a project. My parents, Bruce and Sharon Stokes, for reading and critiquing my writing along the way. My friends and loved-ones, who have offered me their support and continued encouragement in completing my thesis. 2 Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 CHAPTER ONE: Martí and the Historical Roots of the Cuban Revolution, 1895-1952 12 CHAPTER TWO: Revolution, Falling Out, and Change in Course, 1952-1959 34 CHAPTER THREE: Consolidating a Martían Communism, 1959-1962 71 Concluding Remarks 88 Bibliography 91 3 Abstract What prompted Fidel Castro to choose a communist path for the Cuban Revolution? There is no way to know for sure what the cause of Castro’s decision to state the Marxist nature of the revolution was. However, we can know the factors that contributed to this ideological shift. This thesis will argue that the decision to radicalize the revolution and develop a relationship with the Cuban communists was the only logical choice available to Castro in order to fulfill Jose Marti’s, Cuba’s nationalist hero, vision of an independent Cuba. -

The Great Chilean Recovery: Assigning Responsibility for the Chilean Miracle(S)

ABSTRACT THE GREAT CHILEAN RECOVERY: ASSIGNING RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CHILEAN MIRACLE(S) September 11, 1973, a day etched in the memory of Chilean history, marked the abrupt end to the socialist government of Salvador Allende, via a military coup led by the General of the Army, Augusto Pinochet. Although condemned by many for what they consider the destruction of Chile’s democratic tradition, the administrative appointments made and decisions taken by Pinochet and his advisors established policies necessary for social changes and reversed economic downward trends, a phenomenon known as the “Chilean Miracle.” Pinochet, with the assistance of his economic advisors, known as the “Chicago Boys,” established Latin America's first neoliberal regime, emphasizing that a free-market, not the government, should regulate the economy. Examining the processes through which Pinochet formed his team of economic advisors, my research focuses on the transformations wrought by the Chicago Boys on the economic landscape of Chile. These changes have assured that twenty-four years after Pinochet’s rule, the Chilean economy remains a model for Latin American nations. In particular, this examination seeks to answer the following question: Who was responsible for the “Chilean Miracle”? William Ray Mask II May 2013 THE GREAT CHILEAN RECOVERY: ASSIGNING RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CHILEAN MIRACLE(S) by William Ray Mask II A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the College of Social Sciences California State University, Fresno May 2013 APPROVED For the Department of History: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. -

Review of Julia E. Sweig's Inside the Cuban Revolution

Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground. By Julia E. Sweig. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002. xx, 255 pp. List of illustrations, acknowledgments, abbre- viations, about the research, notes, bibliography, index. $29.95 cloth.) Cuban studies, like former Soviet studies, is a bipolar field. This is partly because the Castro regime is a zealous guardian of its revolutionary image as it plays into current politics. As a result, the Cuban government carefully screens the writings and political ide- ology of all scholars allowed access to official documents. Julia Sweig arrived in Havana in 1995 with the right credentials. Her book preface expresses gratitude to various Cuban government officials and friends comprising a who's who of activists against the U.S. embargo on Cuba during the last three decades. This work, a revision of the author's Ph.D. dissertation, ana- lyzes the struggle of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement (M-26-7) against the Fulgencio Batista dictatorship from November 1956 to July 1958. Sweig recounts how the M-26-7 urban underground, which provided the recruits, weapons, and funds for the guerrillas in the mountains, initially had a leading role in decision making, until Castro imposed absolute control over the movement. The "heart and soul" of this book is based on nearly one thousand his- toric documents from the Cuban Council of State Archives, previ- ously unavailable to scholars. Yet, the author admits that there is "still-classified" material that she was unable to examine, despite her repeated requests, especially the correspondence between Fidel Castro and former president Carlos Prio, and the Celia Sánchez collection. -

University of Miami Cuban Heritage Collection Finding

University of Miami Cuban Heritage Collection Finding Aid - Tad Szulc Collection of Interview Transcripts (CHC0189) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.0 Printed: May 21, 2018 Language of description: English University of Miami Cuban Heritage Collection Roberto C. Goizueta Pavilion 1300 Memorial Drive Coral Gables FL United States 33146 Telephone: (305) 284-4900 Fax: (305) 284-4901 Email: [email protected] https://library.miami.edu/chc/ https://atom.library.miami.edu/index.php/chc0189 Tad Szulc Collection of Interview Transcripts Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Series descriptions .......................................................................................................................................... -

William Roseberry, Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Peasants and Capital: Dominica in the World Economy

Book Reviews -William Roseberry, Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Peasants and capital: Dominica in the world economy. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Johns Hopkins Studies in Atlantic History and Culture, 1988. xiv + 344 pp. -Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Robert A. Myers, Dominica. Oxford, Santa Barbara, Denver: Clio Press, World Bibliographic Series, volume 82. xxv + 190 pp. -Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Robert A. Myers, A resource guide to Dominica, 1493-1986. New Haven: Human Area Files, HRA Flex Books, Bibliography Series, 1987. 3 volumes. xxxv + 649. -Stephen D. Glazier, Colin G. Clarke, East Indians in a West Indian town: San Fernando, Trinidad, 1930-1970. London: Allen and Unwin, 1986 xiv + 193 pp. -Kevin A. Yelvington, M.G. Smith, Culture, race and class in the Commonwealth Caribbean. Foreword by Rex Nettleford. Mona: Department of Extra-Mural Studies, University of the West Indies, 1984. xiv + 163 pp. -Aart G. Broek, T.F. Smeulders, Papiamentu en onderwijs: veranderingen in beeld en betekenis van de volkstaal op Curacoa. (Utrecht Dissertation), 1987. 328 p. Privately published. -John Holm, Peter A. Roberts, West Indians and their language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988 vii + 215 pp. -Kean Gibson, Francis Byrne, Grammatical relations in a radical Creole: verb complementation in Saramaccan. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, Creole Language Library, vol. 3, 1987. xiv + 294 pp. -Peter L. Patrick, Pieter Muysken ,Substrata versus universals in Creole genesis. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, Creol Language Library - vol 1, 1986. 315 pp., Norval Smith (eds) -Jeffrey P. Williams, Glenn G. Gilbert, Pidgin and Creole languages: essays in memory of John E.