Sino-Venezuelan Relations: Beyond Oil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agreements That Have Undermined Venezuelan Democracy Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxthe Chinaxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Deals Agreements That Have Undermined Venezuelan Democracy

THE CHINA DEALS Agreements that have undermined Venezuelan democracy xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxThe Chinaxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Deals Agreements that have undermined Venezuelan democracy August 2020 1 I Transparencia Venezuela THE CHINA DEALS Agreements that have undermined Venezuelan democracy Credits Transparencia Venezuela Mercedes De Freitas Executive management Editorial management Christi Rangel Research Coordinator Drafting of the document María Fernanda Sojo Editorial Coordinator María Alejandra Domínguez Design and layout With the collaboration of: Antonella Del Vecchio Javier Molina Jarmi Indriago Sonielys Rojas 2 I Transparencia Venezuela Introduction 4 1 Political and institutional context 7 1.1 Rules of exchange in the bilateral relations between 12 Venezuela and China 2 Cash flows from China to Venezuela 16 2.1 Cash flows through loans 17 2.1.1 China-Venezuela Joint Fund and Large 17 Volume Long Term Fund 2.1.2 Miscellaneous loans from China 21 2.2 Foreign Direct Investment 23 3 Experience of joint ventures and failed projects 26 3.1 Sinovensa, S.A. 26 3.2 Yutong Venezuela bus assembly plant 30 3.3 Failed projects 32 4 Governance gaps 37 5 Lessons from experience 40 5.1 Assessment of results, profits and losses 43 of parties involved 6 Policy recommendations 47 Annex 1 52 List of Venezuelan institutions and officials in charge of negotiations with China Table of Contents Table Annex 2 60 List of unavailable public information Annex 3 61 List of companies and agencies from China in Venezuela linked to the agreements since 1999 THE CHINA DEALS Agreements that have undermined Venezuelan democracy The People’s Republic of China was regarded by the Chávez and Maduro administrations as Venezuela’s great partner with common interests, co-signatory of more than 500 agreements in the past 20 years, and provider of multimillion-dollar loans that have brought about huge debts to the South American country. -

Annual Reportreport

(Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Stock Code: 691 20092009 AnnualAnnual ReportReport Annual Report 2009Annual Report 2009 Headquarter: Sunnsy Industrial Park, Gushan Town, Changqing District, Jinan, Shandong, China Hong Kong Office: Room 2609, 26/F, Tower 2, Lippo Centre, 89 Queensway, Admiralty, Hong Kong Contents DEFINITIONS 2 I COMPANY PROFILE 3 II CORPORATE INFORMATION 6 III FINANCIAL DATA SUMMARY 14 IV CHANGES IN SHARE CAPITAL AND SHAREHOLDINGS OF SUBSTANTIAL SHAREHOLDERS AND THE DIRECTORS 15 V BASIC INFORMATION ON DIRECTORS, SENIOR MANAGEMENT AND EMPLOYEES 22 VI REPORT ON CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 30 VII MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS 38 VIII REPORT OF THE DIRECTORS 51 IX SIGNIFICANT EVENTS 59 X INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT 61 XI FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 63 China Shanshui Cement Group Limited • Annual Report 2009 1 Definitions In this annual report, unless the context otherwise requires, the following words and expressions have the following meanings: “Company” or “Shanshui Cement” China Shanshui Cement Group Limited “Group” or “Shanshui Group” the Company and its subsidiaries “Reporting Period” 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2009 “Directors” Directors of the Company “Board” Board of Directors of the Company “Stock Exchange” The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited “Listing Rules of the Stock Exchange” the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on the Stock Exchange “SFO” Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap. 571) (as amended, supplemented or otherwise modified from time to time) “Hong Kong” Hong Kong Special -

China's Supply-Side Structural Reforms: Progress and Outlook

China’s supply-side structural reforms: Progress and outlook A report by The Economist Intelligence Unit www.eiu.com The world leader in global business intelligence The Economist Intelligence Unit (The EIU) is the research and analysis division of The Economist Group, the sister company to The Economist newspaper. Created in 1946, we have 70 years’ experience in helping businesses, financial firms and governments to understand how the world is changing and how that creates opportunities to be seized and risks to be managed. Given that many of the issues facing the world have an international (if not global) dimension, The EIU is ideally positioned to be commentator, interpreter and forecaster on the phenomenon of globalisation as it gathers pace and impact. EIU subscription services The world’s leading organisations rely on our subscription services for data, analysis and forecasts to keep them informed about what is happening around the world. We specialise in: • Country Analysis: Access to regular, detailed country-specific economic and political forecasts, as well as assessments of the business and regulatory environments in different markets. • Risk Analysis: Our risk services identify actual and potential threats around the world and help our clients understand the implications for their organisations. • Industry Analysis: Five year forecasts, analysis of key themes and news analysis for six key industries in 60 major economies. These forecasts are based on the latest data and in-depth analysis of industry trends. EIU Consulting EIU Consulting is a bespoke service designed to provide solutions specific to our customers’ needs. We specialise in these key sectors: • Consumer Markets: Providing data-driven solutions for consumer-facing industries, we and our management consulting firm, EIU Canback, help clients to enter new markets and be successful in current markets. -

The Rhetoric of Fidel Castro Brent C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 From the mountains to the podium: the rhetoric of Fidel Castro Brent C. Kice Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kice, Brent C., "From the mountains to the podium: the rhetoric of Fidel Castro" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1766. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. FROM THE MOUNTAINS TO THE PODIUM: THE RHETORIC OF FIDEL CASTRO A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by Brent C. Kice B.A., Loyola University New Orleans, 2002 M.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2004 December 2008 DEDICATION To my wife, Dori, for providing me strength during this arduous journey ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Andy King for all of his guidance, and especially his impeccable impersonations. I also wish to thank Stephanie Grey, Ruth Bowman, Renee Edwards, David Lindenfeld, and Mary Brody for their suggestions during this project. I am so thankful for the care and advice given to me by Loretta Pecchioni. -

The Program of CHINA MINING 2017

The Program of CHINA MINING 2017 Friday, Sept.22nd, 2017 PM Inaugural Meeting of China Mining International Productivity Cooperation Enterprises Alliance (Banquet Hall, 4th Fl, Crown Plaza Hotel, Tianjin Meijiang Center) Hosted by: China Mining Association Chair: Yu Qinghe, Vice President & Secretary-General , China Mining Association 15:30-16:00 Preliminary Meeting: • Discuss Proposal of “China Mining International Productivity Cooperation Enterprises Alliance” (Draft) • Discuss Regulations of “China Mining International Productivity Cooperation Enterprises Alliance” (Draft) • Discuss Candidate for President, Vice Presidents and Secretary-General of the first Council • Participants: Representatives of Founders and Members of the Alliance Inaugural Meeting: • Announce Approval Document of National Development and Reform Commission • Speech by Leader from MLR 16:00-17:00 • Speech by Leader from International Cooperation Center of National Development and Reform Commission • Speech by Founder Representative--China Minmetals • Address by New Elected President of the Council • Inauguration Ceremony(Leaders from MLR, NDRC, Departments of MLR, China Mining Association) 17:30-20:00 "Night of BOC" (No.6 Building, Tianjin Guest House) (Invitation ONLY) Mining Cooperation Communication Cocktail Party of CHINA MINING 2017(Hosted by China Mining Association)(Banquet Hall, 4th Fl, Crown Plaza Hotel, 17:30-21:00 Tianjin Meijiang Center) 1/9 Saturday, Sept.23rd, 2017 AM 08:30-09:00 Doors open to the delegates Opening Ceremony of CHINA MINING Congress and Expo 2017 (Rm. Conference Hall N7, 1st Fl.) Chair: The Hon. Cao Weixing, Deputy Minister, Ministry of Land and Resources, PRC 09:00-9:50 • The Hon. Jiang Daming, Minister of Land and Resources, PRC • The Hon. Wang Dongfeng, Mayor of Tianjin, PRC • H.E. -

Environmental Impacts of China Outward Foreign Direct Investment

GEORGE BUSH SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT AND PUBLIC SERVICE Environmental Impacts of China Outward Foreign Direct Investment Case Studies in Latin America, Mongolia, Myanmar, and Zambia Nour Al-Aameri, Lingxiao Fu, Nicole Garcia, Ryan Mak, Caitlin McGill, Amanda Reynolds, Lucas Vinze Advisor: Dr. Ren Mu Capstone Project for The Nature Conservancy 2012 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 2 Country Report .................................................................................................................................. 6 Part I: China Overview………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 Part 2: South America ........................................................................................................................... 29 Part 3: Mongolia……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….41 Part 4: Myanmar…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…50 Part 5: Zambia……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………68 Policy Recommendations ................................................................................................................ 85 Part I: Environmental Regulation and FDI Debate…………………………………………………..………………………….86 Part II: Case Study Comparisons of OFDI Environmental Legislation and Challenges…………………………87 Part III: NGO Literature Review…………………………………………………………………………………………………………90 Part IV: Recommendations……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….92 2 Executive Summary China’s -

The China Analyst 中国分析家 a Knowledge Tool by the Beijing Axis for Executives with a China Agenda March 2011

The China Analyst 中国分析家 A knowledge tool by The Beijing Axis for executives with a China agenda March 2011 Doing Business in a Fast Changing China Features China in 2030: Outlines of a Chinese Future 6 China’s Construction Industry: Strategic Options for Foreign Players 9 Gearing Up: Engaging China’s Globalising Machinery Industry 12 Clean Coal: China’s Coming Revolution 15 Regulars China Sourcing Strategy 26 China Capital: Inbound/Outbound FDI & Financial Markets 30 Strategy: China Shenhua 34 Regional Focus: China-Africa 39 Regional Focus: China-Australia 44 Regional Focus: China-Latin America 48 Regional Focus: China-Russia 52 The Westward Shift of Growth in China* Five Largest Provincial GDP, USD, Q3 2010 Five Fastest Growing Provincial GDP, % y-o-y, Q3 2010 Guangdong - USD 473.6 bn Tianjin - 17.9% Jiangsu - USD 440.7 bn Hainan - 17.6% Shandong - USD 424.3 bn Chongqing - 17.1% Zhejiang - USD 281.7 bn Shanxi - 15.7% Henan - USD 254.3 bn Ningxia - 15.5% Five Highest Provincial Five Fastest Growing Provincial Average Urban Wages, USD, Q3 20101 Average Urban Wages, % y-o-y, Q3 20102 Beijing - USD 6,845 Shanghai - USD 6,777 Tibet - USD 5,287 Tianjin - USD 5,021 Guangdong - USD 4,281 Hainan - 20.6% Ningxia - 19.6% Xinjiang - 19.4% Gansu - 16.7% Sichuan - 16.0% Five Highest Provincial Total Profits of Five Fastest Growing Provincial Total Profits Industrial Enterprises, USD, Jan-Nov 2010 of Industrial Enterprises, % y-o-y, Jan-Nov 2010 Shandong - USD 81.1 bn Shanxi - 124.6% Jiangsu - USD 71.1 bn -

The Independent Institute and Editor of Other Financial Institutions

VOLUME 19, NUMBER 4 wINTER 2010 Economic Troubles and the Growth of Government by Robert Higgs* he current recession to a head in late September 2008 proved to be the Tand, especially, the re- catalyst for an accelerated decline in real GDP and lated financial panic in the rise in the rate of unemployment. The so-called fall of 2008 have given rise credit crunch in the fall to an extraordinary surge in of 2008 prompted the the U.S. government’s size, Fed, the Treasury, and scope, and power. As I write, the Congress to take a the financial panic has subsided, but series of extraordinary the recession, already the longest actions in quick suc- since the 1930s, seems likely to con- cession. tinue for a long time. Even when it has In September 2008, passed, however, the government will the Federal Reserve Sys- certainly retain much tem (“the Fed”) took of the augmentation control of the insurance it has gained recently. giant American International Group Hence, this crisis will (AIG), and the Federal Housing Fi- prove to be the occasion nance Authority took over the huge for another episode of government-sponsored enterprises the ratchet effect in the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, secondary lending growth of government. institutions that held or insured more than half of According to the Na- the total value of U.S. residential mortgages. On tional Bureau of Eco- October 3, the president signed the Emergency nomic Research, the recession began early in Economic Stabilization Act, which, among other 2008, but the decline became severe only in the things, created the Troubled Assets Relief Program latter part of the year. -

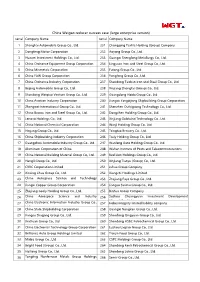

China Weigao Reducer Success Case (Large Enterprise Version) Serial Company Name Serial Company Name

China Weigao reducer success case (large enterprise version) serial Company Name serial Company Name 1 Shanghai Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 231 Chongqing Textile Holding (Group) Company 2 Dongfeng Motor Corporation 232 Aoyang Group Co., Ltd. 3 Huawei Investment Holdings Co., Ltd. 233 Guangxi Shenglong Metallurgy Co., Ltd. 4 China Ordnance Equipment Group Corporation 234 Lingyuan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 5 China Minmetals Corporation 235 Futong Group Co., Ltd. 6 China FAW Group Corporation 236 Yongfeng Group Co., Ltd. 7 China Ordnance Industry Corporation 237 Shandong Taishan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 8 Beijing Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 238 Xinjiang Zhongtai (Group) Co., Ltd. 9 Shandong Weiqiao Venture Group Co., Ltd. 239 Guangdong Haida Group Co., Ltd. 10 China Aviation Industry Corporation 240 Jiangsu Yangzijiang Shipbuilding Group Corporation 11 Zhengwei International Group Co., Ltd. 241 Shenzhen Oufeiguang Technology Co., Ltd. 12 China Baowu Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 242 Dongchen Holding Group Co., Ltd. 13 Lenovo Holdings Co., Ltd. 243 Xinjiang Goldwind Technology Co., Ltd. 14 China National Chemical Corporation 244 Wanji Holding Group Co., Ltd. 15 Hegang Group Co., Ltd. 245 Tsingtao Brewery Co., Ltd. 16 China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation 246 Tasly Holding Group Co., Ltd. 17 Guangzhou Automobile Industry Group Co., Ltd. 247 Wanfeng Auto Holding Group Co., Ltd. 18 Aluminum Corporation of China 248 Wuhan Institute of Posts and Telecommunications 19 China National Building Material Group Co., Ltd. 249 Red Lion Holdings Group Co., Ltd. 20 Hengli Group Co., Ltd. 250 Xinjiang Tianye (Group) Co., Ltd. 21 CRRC Corporation Limited 251 Juhua Group Company 22 Xinxing Jihua Group Co., Ltd. -

The Great Chilean Recovery: Assigning Responsibility for the Chilean Miracle(S)

ABSTRACT THE GREAT CHILEAN RECOVERY: ASSIGNING RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CHILEAN MIRACLE(S) September 11, 1973, a day etched in the memory of Chilean history, marked the abrupt end to the socialist government of Salvador Allende, via a military coup led by the General of the Army, Augusto Pinochet. Although condemned by many for what they consider the destruction of Chile’s democratic tradition, the administrative appointments made and decisions taken by Pinochet and his advisors established policies necessary for social changes and reversed economic downward trends, a phenomenon known as the “Chilean Miracle.” Pinochet, with the assistance of his economic advisors, known as the “Chicago Boys,” established Latin America's first neoliberal regime, emphasizing that a free-market, not the government, should regulate the economy. Examining the processes through which Pinochet formed his team of economic advisors, my research focuses on the transformations wrought by the Chicago Boys on the economic landscape of Chile. These changes have assured that twenty-four years after Pinochet’s rule, the Chilean economy remains a model for Latin American nations. In particular, this examination seeks to answer the following question: Who was responsible for the “Chilean Miracle”? William Ray Mask II May 2013 THE GREAT CHILEAN RECOVERY: ASSIGNING RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE CHILEAN MIRACLE(S) by William Ray Mask II A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the College of Social Sciences California State University, Fresno May 2013 APPROVED For the Department of History: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. -

A Strategic Flip-Flop in the Caribbean 63

Hoover Press : EPP 100 DP5 HPEP000100 23-02-00 rev1 page 62 62 William Ratliff and Roger Fontaine U.S. interference in Cuban affairs. In effect it gives him a veto over U.S. policy. Therefore the path of giving U.S. politicians a “way out” won’t in fact work because Castro will twist it to his interests. Better to just do it unilaterally on our own timetable. For the time being it appears U.S. policy will remain reactive—to Castro and to Cuban American pressure groups—irrespective of the interests of Americans and Cubans as a whole. Like parrots, all presi- dential hopefuls in the 2000 presidential elections propose varying ver- sions of the current failed policy. We have made much here of the negative role of the Cuba lobby, but we close by reiterating that their advocacy has not usually been different in kind from that of other pressure groups, simply much more effective. The buck falls on the politicians who cannot see the need for, or are afraid to support, a new policy for the post–cold war world. Notes 1. This presentation of the issues is based on but goes far beyond written testimony—“U.S. Cuban Policy—a New Strategy for the Future”— which the authors presented to the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Com- mittee on 24 May 1995. We have long advocated this change, beginning with William Ratliff, “The Big Cuba Myth,” San Jose Mercury News,15 December 1992, and William Ratliff and Roger Fontaine, “Foil Castro,” Washington Post, 30 June 1993. -

The Challenge of Bringing Innocence Work to Latin America

California Western School of Law CWSL Scholarly Commons Faculty Scholarship 2012 Redinocente: The Challenge of Bringing Innocence Work to Latin America Justin Brooks California Western School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/fs Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation 80 U. Cin. L. Rev. 1115 (2011-2012) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CWSL Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of CWSL Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REDINOCENTE: THE CHALLENGE OF BRINGING INNOCENCE WORK TO LATIN AMERICA Justin Brooks* t In 2008, I traveled to Oruro, Bolivia to train defense attorneys on DNA technology. I had done similar trainings in Chile, Paraguay, Mexico, and other countries in Latin America, but nowhere that felt quite so remote. The 143-mile bus trip from La Paz passed through dusty villages filled with mud huts and lacking basic infrastructure. The bus stopped many times, picking up Chola women wearing shawls and derby hats, and carrying their huge satchels of goods to sell and trade. It seemed unlikely that the technology I would be talking about would have much value in this remote outpost. My fears were confirmed when I talked to the lawyers I was training in Oruro. They lacked access to basic technology and there were certainly no DNA labs readily available to them. On the other hand, I became optimistic when I talked to the local judges.