Ensuring a Future for the Past Long-Term Preservation Strategies for Digital Archaeological Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collecting and Preserving Digital Materials

COLLECTING AND PRESERVING DIGITAL MATERIALS A HOW-TO GUIDE FOR HISTORICAL SOCIETIES BY SOPHIE SHILLING CONTENTS Foreword Preface 1 Introduction 2 Digital material creation Born-digital materials Digitisation 3 Project planning Write a plan Create a workflow Policies and procedures Funding Getting everyone on-board 4 Select Bitstream preservation File formats Image resolution File naming conventions 5 Describe Metadata 6 Ingest Software Digital storage 7 Access and outreach Copyright Culturally sensitive content 8 Community 9 Glossary Bibliography i Foreword FOREWORD How the collection and research landscape has changed!! In 2000 the Federation of Australian Historical Societies commissioned Bronwyn Wilson to prepare a training guide for historical societies on the collection of cultural materials. Its purpose was to advise societies on the need to gather and collect contemporary material of diverse types for the benefit of future generations of researchers. The material that she discussed was essentially in hard copy format, but under the heading of ‘Electronic Media’ Bronwyn included a discussion of video tape, audio tape and the internet. Fast forward to 2018 and we inhabit a very different world because of the digital revolution. Today a very high proportion of the information generated in our technologically-driven society is created and distributed digitally, from emails to publications to images. Increasingly, collecting organisations are making their data available online, so that the modern researcher can achieve much by simply sitting at home on their computer and accessing information via services such as Trove and the increasing body of government and private material that is becoming available on the web. This creates both challenges and opportunities for historical societies. -

Module 8 Wiki Guide

Best Practices for Biomedical Research Data Management Harvard Medical School, The Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine Module 8 Wiki Guide Learning Objectives and Outcomes: 1. Emphasize characteristics of long-term data curation and preservation that build on and extend active data management ● It is the purview of permanent archiving and preservation to take over stewardship and ensure that the data do not become technologically obsolete and no longer permanently accessible. ○ The selection of a repository to ensure that certain technical processes are performed routinely and reliably to maintain data integrity ○ Determining the costs and steps necessary to address preservation issues such as technological obsolescence inhibiting data access ○ Consistent, citable access to data and associated contextual records ○ Ensuring that protected data stays protected through repository-governed access control ● Data Management ○ Refers to the handling, manipulation, and retention of data generated within the context of the scientific process ○ Use of this term has become more common as funding agencies require researchers to develop and implement structured plans as part of grant-funded project activities ● Digital Stewardship ○ Contributions to the longevity and usefulness of digital content by its caretakers that may occur within, but often outside of, a formal digital preservation program ○ Encompasses all activities related to the care and management of digital objects over time, and addresses all phases of the digital object lifecycle 2. Distinguish between preservation and curation ● Digital Curation ○ The combination of data curation and digital preservation ○ There tends to be a relatively strong orientation toward authenticity, trustworthiness, and long-term preservation ○ Maintaining and adding value to a trusted body of digital information for future and current use. -

International Preservation Issues Number Seven International Preservation Issues Number Seven

PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM THE 3-D’SOFPRESERVATION DISATERS, DISPLAYS, DIGITIZATION ACTES DU SYMPOSIUM INTERNATIONAL LA CONSERVATION EN TROIS DIMENSIONS CATASTROPHES, EXPOSITIONS, NUMÉRISATION Organisé par la Bibliothèque nationale de France avec la collaboration de l’IFLA Paris, 8-10 mars 2006 Ed. revised and updated by / Ed. revue et corrigée par Corine Koch, IFLA-PAC International Preservation Issues Number Seven International Preservation Issues Number Seven International Preservation Issues (IPI) is an IFLA-PAC (Preservation and Conservation) series that intends to complement PAC’s newsletter, International Preservation News (IPN) with reports on major preservation issues. IFLA-PAC Bibliothèque nationale de France Quai François-Mauriac 75706 Paris cedex 13 France Tél : + 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 70 Fax : + 33 (0) 1 53 79 59 80 e-mail: [email protected] IFLA-PAC Director e-mail: [email protected] Programme Officer ISBN-10 2-912 743-05-2 ISBN-13 978-2-912 743-05-3 ISSN 1562-305X Published 2006 by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) Core Activity on Preservation and Conservation (PAC). ∞ This publication is printed on permanent paper which meets the requirements of ISO standard: ISO 9706:1994 – Information and Documentation – Paper for Documents – Requirements for Permanence. © Copyright 2006 by IFLA-PAC. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transcribed in any form without permission of the publishers. Request for reproduction for non-commercial purposes, including -

Metadata Demystified: a Guide for Publishers

ISBN 1-880124-59-9 Metadata Demystified: A Guide for Publishers Table of Contents What Metadata Is 1 What Metadata Isn’t 3 XML 3 Identifiers 4 Why Metadata Is Important 6 What Metadata Means to the Publisher 6 What Metadata Means to the Reader 6 Book-Oriented Metadata Practices 8 ONIX 9 Journal-Oriented Metadata Practices 10 ONIX for Serials 10 JWP On the Exchange of Serials Subscription Information 10 CrossRef 11 The Open Archives Initiative 13 Conclusion 13 Where To Go From Here 13 Compendium of Cited Resources 14 About the Authors and Publishers 15 Published by: The Sheridan Press & NISO Press Contributing Editors: Pat Harris, Susan Parente, Kevin Pirkey, Greg Suprock, Mark Witkowski Authors: Amy Brand, Frank Daly, Barbara Meyers Copyright 2003, The Sheridan Press and NISO Press Printed July 2003 Metadata Demystified: A Guide for Publishers This guide presents an overview of evolving classified according to a variety of specific metadata conventions in publishing, as well as functions, such as technical metadata for related initiatives designed to standardize how technical processes, rights metadata for rights metadata is structured and disseminated resolution, and preservation metadata for online. Focusing on strategic rather than digital archiving, this guide focuses on technical considerations in the business of descriptive metadata, or metadata that publishing, this guide offers insight into how characterizes the content itself. book and journal publishers can streamline the various metadata-based operations at work Occurrences of metadata vary tremendously in their companies and leverage that metadata in richness; that is, how much or how little for added exposure through digital media such of the entity being described is actually as the Web. -

Analog, the Sequel: an Analysis of Current Film Archiving Practice and Hesitance to Embrace Digital Preservation by Suzanna Conrad

ANALOG, THE SEQUEL: AN ANALYSIS OF CURRENT FILM ARCHIVING PRACTICE AND HESITANCE TO EMBRACE DIGITAL PRESERVATION BY SUZANNA CONRAD ABSTRACT: Film archives preserve materials of significant cultural heritage. While current practice helps ensure 35mm film will last for at least one hundred years, digi- tal technology is creating new challenges for the traditional means of preservation. Digitally produced films can be preserved via film stock; however, digital ancillary materials and assets in many cases cannot be preserved using traditional analog means. Strategy and action for preserving this content needs to be addressed before further content is lost. To understand the current perspective of the film archives, especially in regards to the film industry’s marked hesitation to embrace digital preservation, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ paper “The Digital Dilemma: Strategic Issues in Archiving and Accessing Digital Motion Picture Materials” was closely evaluated. To supplement this analysis, an interview was conducted with the collections curator at the Academy Film Archive, who explained the archives’ current approach to curation and its hesitation to move to digital technologies for preservation. Introduction Moving images are a vital part of our cultural heritage. The music, film, and broadcasting industries, as well as academic and cultural institutions, have amassed a “legacy of primary source materials” of immense value. These sources make the last one hundred years understandable as an era of the “media of the modernity.”1 Motion pictures and films were established as vital archival records as early as the 1930s with the National Archives Act, which included motion pictures in the definition of “objects of archival interest.”2 As cultural artifacts, moving images deserve archival care and preservation.3 However, the art of preserving moving images and film can at times be daunting. -

2016 Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Cultural Heritage Materials

September 2016 Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Cultural Heritage Materials Creation of Raster Image Files i Document Information Title Editor Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Cultural Heritage Materials: Thomas Rieger Creation of Raster Image Files Document Type Technical Guidelines Publication Date September 2016 Source Documents Title Editors Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Cultural Heritage Materials: Don Williams and Michael Creation of Raster Image Master Files Stelmach http://www.digitizationguidelines.gov/guidelines/FADGI_Still_Image- Tech_Guidelines_2010-08-24.pdf Document Type Technical Guidelines Publication Date August 2010 Title Author s Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Archival Records for Electronic Steven Puglia, Jeffrey Reed, and Access: Creation of Production Master Files – Raster Images Erin Rhodes http://www.archives.gov/preservation/technical/guidelines.pdf U.S. National Archives and Records Administration Document Type Technical Guidelines Publication Date June 2004 This work is available for worldwide use and reuse under CC0 1.0 Universal. ii Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 7 SCOPE .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 THE FADGI STAR SYSTEM ....................................................................................................................... -

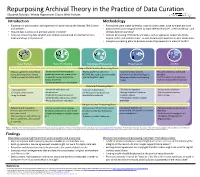

Repurposing Archival Theory in the Practice of Data Curation

Repurposing Archival Theory in the Practice of Data Curation Elizabeth Rolando| Wendy Hagenmaier |Susan Wells Parham Introduction Methodology • Expansion of data curation and digital archiving services at the Georgia Tech Library • Process the same digital collection, once by data curator, once by digital archivist and Archives. • Data curation processing informed by OAIS Reference Model1, ICPSR workflow2, and • How do data curation and archival science intersect? UK Data Archive workflow3 • How can comparing data curation and archival science lead to improvements in • Archival processing informed by concepts, such as appraisal, respect des fonds, local workflows and practices? original order, and archival value4, as well documented practices at peer institutions • Compare processing plans to discover areas of agreement and areas of conflict Data Transfer Data Processing Metadata Processing Preservation Access Unique Data Curation Processing Steps -Deposit agreement modeled on -Format transformation policies -Review and enhancement of -Varied retention periods, -Datasets treated as active and institutional repository license guided by reuse over preservation README file, used to accommodate determined by Board of Regents reusable -Funding model for sustainability -Create derivatives to promote diverse depositor needs Retention Schedule and funding -Datasets linked to publications access and re-use model -Bulk or individual file download -Correct erroneous or missing data Common Processing Steps -Data quarantine -Format identification -

Instructions and Dehinitions: FY2014

Instructions and Deinitions: FY2014 Table of Contents Introduction 2 Background 2 What’s New for the FY2014 Survey 2 FAQ 4 General Instructions 6 General Information 6 Section 1: Conservation Treatment 8 Section 2: Conservation Assessment, Digitization Preparation, Exhibit Preparation 9 Section 3: General Preservation Activities 10 Section 4: Reformatting and Digitization 10 Section 5: Digital Preservation and Digital Asset Management 13 Introduction Count what you do and show preservation counts! The Preservation Statistics Survey is an effort coordinated by the Preservation and Reformatting Section (PARS) of the American Library Association (ALA) and the Association of Library Collections and Technical Services (ALCTS). Any library or archives in the United States conducting preservation activities may complete this survey, which will be open from January 20, 2015 through February 27, 2015. The deadline has been extended to March 20, 2015. Questions focus on production-based preservation activities for /iscal year 2014, documenting your institution's conservation treatment, general preservation activities, preservation reformatting and digitization, and digital preservation and digital asset management activities. The goal of this survey is to document the state of preservation activities in this digital era via quantitative data that facilitates peer comparison and tracking changes in the preservation and conservation /ields over time. Background This survey is based on the Preservation Statistics survey program by the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) from 1984 to 2008. When the ARL Preservation Statistics program was discontinued in 2008, the Preservation and Reformatting Section of ALA / ALCTS, realizing the value of sharing preservation statistics, worked towards developing an improved and sustainable preservation statistics survey. -

The Concept of Appraisal and Archival Theory

328 American Archivist / Vol. 57 / Spring 1994 Research Article Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/57/2/328/2748653/aarc_57_2_pu548273j5j1p816.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 The Concept of Appraisal and Archival Theory LUCIANA DURANTI Abstract: In the last decade, appraisal has become one of the central topics of archival literature. However, the approach to appraisal issues has been primarily methodological and practical. This article discusses the theoretical implications of appraisal as attribution of value to archives, and it bases its argument on the nature of archival material as defined by traditional archival theory. About the author: Luciana Duranti is associate professor in the Master of Archival Studies Pro- gram, School of Library, Archival, and Information Studies, at the University of British Columbia. Before leaving Italy for Canada in 1987, she was professor-researcher in the Special School for Archivists and Librarians at the University of Rome. She obtained that position in 1982, after having held archival and teaching posts in the State Archives of Rome and its School, and in the National Research Council. She earned a doctorate in arts from the University of Rome (1973) and graduate degrees in archival science and diplomatics and paleography from the University of Rome (1975) and the School of the State Archives of Rome (1979) respectively. The Concept of Appraisal and Archival Theory 329 Appraisal is the process of establishing the preceded by an exploration of the concept value of documents made or received in the of appraisal in the context of archival the- course of the conduct of affairs, qualifying ory, but only by a continuous reiteration of that value, and determining its duration. -

Infusing Consumer Data Reuse Practices Into Curation and Preservation Activities

San Diego, CA, 11 August 2012 76th Annual Meeting of the Society of American Archivists Infusing Consumer Data Reuse Practices into Curation and Preservation Activities Ixchel M. Faniel, Ph. D. OCLC Research [email protected] This project is possible with funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The world’s libraries. Connected. Agenda DIPIR: A Project Overview Reuse Practices of Quantitative Social Scientists & Archaeologists Q&A The world’s libraries. Connected. An Overview: www.dipir.org The DIPIR Project The world’s libraries. Connected. Research Team Nancy McGovern ICPSR/MIT Elizabeth Ixchel Faniel Yakel OCLC University of Research Michigan (Co-PI) DIPIR (PI) Project William Fink Eric Kansa UM Museum Open of Zoology Context The world’s libraries. Connected. Research Motivation Our interest is in this overlap. Two Major Goals 1. Bridge gap between Data reuse data reuse and digital research curation research 2. Determine whether reuse and curation Disciplines Digital practices can be curating and curation generalized across reusing data research disciplines Faniel & Yakel (2011) The world’s libraries. Connected. Research Questions 1. What are the significant properties of data that facilitate reuse in the quantitative social science, archaeology, and ecology communities? 2. How can these significant properties be expressed as representation information to ensure the preservation of meaning and enable data reuse? The world’s libraries. Connected. Research Methodology Sep 2012 – Sep 2013 Phase 3: May 2011 – Apr 2013 Mapping Significant Phase 2: Properties as Collecting & Representation Analyzing User Information Data across the Oct 2010 – Jun 2011 Three Sites Phase 1: Project Start up The world’s libraries. -

Don't WARC Away: Preservation Metadata & Web Archives

Don't WARC Away: Preservation Metadata & Web Archives! Jefferson Bailey & Maria LaCalle, Internet Archive ALA 2015 | ALCTS PARS | June 27, 2015 @jefferson_bail | [email protected] Don't WARC Away: Preservation Metadata & Web Archives! Jefferson Bailey & Maria LaCalle, Internet Archive ALA 2015 | ALCTS PARS | June 27, 2015 @jefferson_bail | [email protected] •! We are a non-profit Digital Library & Archive founded in 1996 •! 20+PB unique data: 10PB web, ~8m text, 2m vid, 2m aud, 100K soft, etc •! We work in a former church and it’s awesome •! Developed: Heritrix, Wayback, warcprox, Umbra, NutchWax, ARC format •! Engineers, librarians/archivists, program staff •! https://archive.org/web •! Largest and oldest publicly available web archive in existence •! 485,000,000,000+ URLs (that’s billions) •! Like a billion websites, domain agnostic •! Content in 40+ Languages •! Periodic snapshot; 1b+ URLs per week •! https://archive-it.org/ •! Web archiving service used by 370+ institutions •! 3500+ collection, 10 billion+ URLs •! 49 states and 19 countries •! Libraries, archives, museums, governments, non-profits, etc. •! User groups, Annual Meeting, collaborative and educational projects What is a web archive? •! Web archiving is the process of collecting portions of web content, preserving the collections, and then providing access to the archives - for use and re use. •! A web archive is a collection of archived URLs grouped by theme, event, subject area, or web address. •! A web archive contains as much as possible from the original resources and documents the change over time. It recreates the experience a user would have had if they!had visited the live site on the day it was archived. -

Content Preservation and Digitization of Maps Housed in the KU Natural History Museum Division of Archaeology: an Analysis of Op

1 Content Preservation and Digitization of Maps Housed in the KU Natural History Museum Division of Archaeology: An Analysis of Opportunities and Obstacles By Ross Kerr A study presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Museum Studies The University of Kansas April 27 2017 *Address for correspondence: [email protected] *With special thanks to Dr. Sandra Olsen, Dr. Peter Welsh, and Mr. Steve Nowak for serving on my committee and overseeing my research. 2 Abstract The purpose of this research is to explain the obstacles museums face in preserving map collections, as well as the steps museums can take to overcome these obstacles. The research begins with a brief history of paper conservation of maps in museums and libraries, and digitization of maps. Next, there is an explanation of the theoretical framework/approach that is used in this project. Following that is a presentation of a SWOT analysis of the archaeological map collection held by the KU Biodiversity Institute & Natural History Museum. The first two components of the SWOT analysis, strengths and weaknesses, focus on advantages and shortcomings of the collection in its current state. The last two components, opportunities and threats, focus respectively on the benefits that can be expected from preserving the map collection, and the obstacles that may hinder process. Finally, the study outlines a procedure for preserving and digitizing the archaeological maps held by the KU Biodiversity Institute, in order to expand accessibility