International Preservation Issues Number Seven International Preservation Issues Number Seven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

A/V Material Resources Webinars, Videos Connecting to Collections

A/V Material Resources Webinars, Videos Connecting to Collections – Caring for Audiovisual material https://www.connectingtocollections.org/av/ CCAHA – A Race Against Time: Preserving AV Media https://ccaha.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2018- 07/A%20Race%20Against%20Time%20Summary.pdf ALCTS – Moving Image Preservation 101 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rb77uztb_IU Leaflets / Quick Reference Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/preservation/care/record.html https://www.loc.gov/preservation/about/faqs/audio.html Video Format Id Guide Sarah Stauderman & Paul Messier https://cool.culturalheritage.org/videopreservation/vid_id/ Texas Commission on the Arts- Videotape Identification and Assessment Guide https://www.arts.texas.gov/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/video.pdf Film Care https://filmcare.org/ mini Disc http://www.minidisc.org/index.php In depth reference NEDCC - Fundamentals of AV Preservation Texbook https://www.nedcc.org/fundamentals-of-av-preservation-textbook/chapter1-care-and- handling-of-audiovisual-collections National Film and Sound Archive of Australia https://www.nfsa.gov.au/preservation/guide/handbook Washington State Film Preservation Manual https://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/collections/film-preservation-manual/ National Film Preservation Foundation – guide to film preservation https://www.filmpreservation.org/preservation-basics/the-film-preservation-guide http://www.folkstreams.net/vafp/guide.php The State of Recorded Sound Preservation in the United States http://www.clir.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/pub148.pdf -

Songs by Artist

Sunfly (All) Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Comic Relief) Vanessa Jenkins & Bryn West & Sir Tom Jones & 3OH!3 Robin Gibb Don't Trust Me SFKK033-10 (Barry) Islands In The Stream SF278-16 3OH!3 & Katy Perry £1 Fish Man Starstrukk SF286-11 One Pound Fish SF12476 Starstrukk SFKK038-10 10cc 3OH!3 & Kesha Dreadlock Holiday SF023-12 My First Kiss SFKK046-03 Dreadlock Holiday SFHT004-12 3SL I'm Mandy SF079-03 Take It Easy SF191-09 I'm Not In Love SF001-09 3T I'm Not In Love SFD701-6-05 Anything FLY032-07 Rubber Bullets SF071-01 Anything SF049-02 Things We Do For Love, The SFMW832-11 3T & Michael Jackson Wall Street Shuffle SFMW814-01 Why SF080-11 1910 Fruitgum Company 3T (Wvocal) Simon Says SF028-10 Anything FLY032-15 Simon Says SFG047-10 4 Non Blondes 1927 What's Up SF005-08 Compulsory Hero SFDU03-03 What's Up SFD901-3-14 Compulsory Hero SFHH02-05-10 What's Up SFHH02-09-15 If I Could SFDU09-11 What's Up SFHT006-04 That's When I Think Of You SFID009-04 411, The 1975, The Dumb SF221-12 Chocolate SF326-13 On My Knees SF219-04 City, The SF329-16 Teardrops SF225-06 Love Me SF358-13 5 Seconds Of Summer Robbers SF341-12 Amnesia SF342-12 Somebody Else SF367-13 Don't Stop SF340-17 Sound, The SF361-08 Girls Talk Boys SF366-16 TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME SF390-09 Good Girls SF345-07 UGH SF360-09 She Looks So Perfect SF338-05 2 Eivissa She's Kinda Hot SF355-04 Oh La La La SF114-10 Youngblood SF388-08 2 Unlimited 50 Cent No Limit FLY027-05 Candy Shop SF230-10 No Limit SF006-05 Candy Shop SFKK002-09 No Limit SFD901-3-11 In Da -

Analog, the Sequel: an Analysis of Current Film Archiving Practice and Hesitance to Embrace Digital Preservation by Suzanna Conrad

ANALOG, THE SEQUEL: AN ANALYSIS OF CURRENT FILM ARCHIVING PRACTICE AND HESITANCE TO EMBRACE DIGITAL PRESERVATION BY SUZANNA CONRAD ABSTRACT: Film archives preserve materials of significant cultural heritage. While current practice helps ensure 35mm film will last for at least one hundred years, digi- tal technology is creating new challenges for the traditional means of preservation. Digitally produced films can be preserved via film stock; however, digital ancillary materials and assets in many cases cannot be preserved using traditional analog means. Strategy and action for preserving this content needs to be addressed before further content is lost. To understand the current perspective of the film archives, especially in regards to the film industry’s marked hesitation to embrace digital preservation, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ paper “The Digital Dilemma: Strategic Issues in Archiving and Accessing Digital Motion Picture Materials” was closely evaluated. To supplement this analysis, an interview was conducted with the collections curator at the Academy Film Archive, who explained the archives’ current approach to curation and its hesitation to move to digital technologies for preservation. Introduction Moving images are a vital part of our cultural heritage. The music, film, and broadcasting industries, as well as academic and cultural institutions, have amassed a “legacy of primary source materials” of immense value. These sources make the last one hundred years understandable as an era of the “media of the modernity.”1 Motion pictures and films were established as vital archival records as early as the 1930s with the National Archives Act, which included motion pictures in the definition of “objects of archival interest.”2 As cultural artifacts, moving images deserve archival care and preservation.3 However, the art of preserving moving images and film can at times be daunting. -

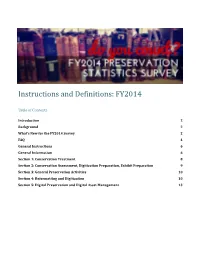

Instructions and Dehinitions: FY2014

Instructions and Deinitions: FY2014 Table of Contents Introduction 2 Background 2 What’s New for the FY2014 Survey 2 FAQ 4 General Instructions 6 General Information 6 Section 1: Conservation Treatment 8 Section 2: Conservation Assessment, Digitization Preparation, Exhibit Preparation 9 Section 3: General Preservation Activities 10 Section 4: Reformatting and Digitization 10 Section 5: Digital Preservation and Digital Asset Management 13 Introduction Count what you do and show preservation counts! The Preservation Statistics Survey is an effort coordinated by the Preservation and Reformatting Section (PARS) of the American Library Association (ALA) and the Association of Library Collections and Technical Services (ALCTS). Any library or archives in the United States conducting preservation activities may complete this survey, which will be open from January 20, 2015 through February 27, 2015. The deadline has been extended to March 20, 2015. Questions focus on production-based preservation activities for /iscal year 2014, documenting your institution's conservation treatment, general preservation activities, preservation reformatting and digitization, and digital preservation and digital asset management activities. The goal of this survey is to document the state of preservation activities in this digital era via quantitative data that facilitates peer comparison and tracking changes in the preservation and conservation /ields over time. Background This survey is based on the Preservation Statistics survey program by the Association of Research Libraries (ARL) from 1984 to 2008. When the ARL Preservation Statistics program was discontinued in 2008, the Preservation and Reformatting Section of ALA / ALCTS, realizing the value of sharing preservation statistics, worked towards developing an improved and sustainable preservation statistics survey. -

University of Arizona, Planning for the Sustainable Preservation of At-Risk

DIVISION OF PRESERVATION AND ACCESS Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the NEH Division of Preservation and Access application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/divisions/preservation for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Preservation and Access staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Planning for the Sustainable Preservation of At-Risk Film in the Center for Creative Photography Archives Institution: University of Arizona Project Director: Alexis Peregoy Grant Program: Sustaining Cultural Heritage Collections Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona Page 1 of 12 “Planning for the Sustainable Preservation of At-Risk Film in the CCP Archives” NARRATIVE INTRODUCTION Project overview. The Center for Creative Photography (CCP) at the University of Arizona (UA) seeks a $40,000 grant to plan for the sustainable preservation of at-risk film-based materials found within the archive collections. The film-based materials include cellulose nitrate and acetate negatives, slides, transparencies, and film reels from the late 19th century through the 20th century. -

Collections Care Paper, Photographs, Textiles & Books

guide to Collections Care Paper, Photographs, Textiles & Books PLUS, check out our Resource Section for more information on preservation and conservation. see pages 56-60. call: 1-800-448-6160 fax: 1-800-272-3412 web: Gaylord.com GayYlouro Trustedrd Source™ A CONTINUUM OF CARE Gaylord’s commitment to libraries and the care of their collec- tions dates back more than eighty years. In 1924, the company published Bookcraft, its first training manual for the repair of books in school and public libraries. Updated regularly, the publication has provided librarians with simple cost-effective techniques for the care of their collections. When the field of preservation expanded during the 1980s, Gaylord responded with a line of archival products. In 1992, it issued its first Archival Supplies Catalog, followed by its innova- tive series of Pathfinders. Written by conservators, these illustrated guides earned a reputation for reliable information on the care and storage of paper, photographs, textiles, and books. This Guide to Collections Care continues Gaylord’s commitment to providing its users with the reliable information they need to preserve their treasures. Conservators have updated the information from our original Pathfinders and combined all five booklets into this one easy guide. We have also added product references as a convenient resource tool. ©2010, Gaylord Bros., Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in USA Gaylord Bros. PO Box 4901 Syracuse, NY 13221-4901 Gaylord Bros. gratefully acknowledges the authors of this pamphlet: Nancy Carlson -

The Digital Dilemma 2 Perspectives from Independent Filmmakers, Documentarians and Nonprofi T Audiovisual Archives

Copyright ©2012 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. “Oscar,” “Academy Award,” and the Oscar statuette are registered trademarks, and the Oscar statuette the copyrighted property, of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The accuracy, completeness, and adequacy of the content herein are not guaranteed, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences expressly disclaims all warranties, including warranties of merchantability, fi tness for a particular purpose and non-infringement. Any legal information contained herein is not legal advice, and is not a substitute for advice of an attorney. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this document may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publisher. Published by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Inquiries should be addressed to: Science and Technology Council Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences 1313 Vine Street, Hollywood, CA 90028 (310) 247-3000 http://www.oscars.org Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Digital Dilemma 2 Perspectives from Independent Filmmakers, Documentarians and Nonprofi t Audiovisual Archives 1. Digital preservation – Case Studies. 2. Film Archives – Technological Innovations 3. Independent Filmmakers 4. Documentary Films 5. Audiovisual I. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Content Preservation and Digitization of Maps Housed in the KU Natural History Museum Division of Archaeology: an Analysis of Op

1 Content Preservation and Digitization of Maps Housed in the KU Natural History Museum Division of Archaeology: An Analysis of Opportunities and Obstacles By Ross Kerr A study presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Museum Studies The University of Kansas April 27 2017 *Address for correspondence: [email protected] *With special thanks to Dr. Sandra Olsen, Dr. Peter Welsh, and Mr. Steve Nowak for serving on my committee and overseeing my research. 2 Abstract The purpose of this research is to explain the obstacles museums face in preserving map collections, as well as the steps museums can take to overcome these obstacles. The research begins with a brief history of paper conservation of maps in museums and libraries, and digitization of maps. Next, there is an explanation of the theoretical framework/approach that is used in this project. Following that is a presentation of a SWOT analysis of the archaeological map collection held by the KU Biodiversity Institute & Natural History Museum. The first two components of the SWOT analysis, strengths and weaknesses, focus on advantages and shortcomings of the collection in its current state. The last two components, opportunities and threats, focus respectively on the benefits that can be expected from preserving the map collection, and the obstacles that may hinder process. Finally, the study outlines a procedure for preserving and digitizing the archaeological maps held by the KU Biodiversity Institute, in order to expand accessibility -

Jts2019 Collaborative Notes

Joint Technical Symposium (JTS) PRESERVE THE LEGACY | CELEBRATE THE FUTURE HILVERSUM, 3-5 OCTOBER 2019 ▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁▁ Image credit: Melanie Lemahieu, melanielemahieu.com, CC BY-SA JTS2019 COLLABORATIVE NOTES taken by Erwin Verbruggen, Joshua Ng, Rasa Bočytė, and Ross Garrett. JTS2019 was organized on behalf of the Coordinating Council of Audiovisual Archiving Associations (CCAAA) by AMIA, FIAF, FIAT/IFTA, and IASA. JTS2019 was held in conjunction with the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives (IASA) 50th Anniversary conference and hosted by the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3835666 About JTS The Joint Technical Symposium (JTS) is the international scientific and technical event hosted by the audiovisual archives associations that make up the CCAAA. Held every few years, this joint event brings together technical experts from around the world to share information and research about the preservation of original image and sound materials. The 2019 JTS was organized by AMIA, FIAF, FIAT/IFTA, and IASA on behalf of the CCAAA JTS 2019 was held October 3-5, 2019 in conjunction with the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives (IASA) conference and hosted by the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision in Hilversum, the Netherlands. About CCAAA The professional archivists that the CCAAA ultimately represents work in institutions such as archives, libraries and museums at national and local level, university teaching and research departments, and broadcast and production organisations. Jts2019.com https://www.ccaaa.org/pages/news-and-activities/joint-technical-symposium.html JTS2019 DOCUMENTATION JTS2019 Twitter archive as TAGSExplorer or TAGS Archive JTS2019 images on IASA’s Flickr Selected conference recordings on Sound and Vision’s Vimeo Slide decks on OSF Meetings Verbruggen, Erwin, Joshua Ng, Rasa Bočytė, and Ross Garrett. -

NORTHEAST HISTORIC FILM Jbn F7 1993 [, / / I I PO BOX 900, MAIN ST, BUCKSPORT, ME 04416-0900 1

LIBRARY OF COiiGRESS , NORTHEAST HISTORIC FILM JbN F7 1993 [, / / I I PO BOX 900, MAIN ST, BUCKSPORT, ME 04416-0900 1 Northeast Historic Film would like to bring to the National Film Preservation Board study on the current state of film preservation a statement concerning the significance, and the imperilled state, of the nontheatrical film record. This archives was established to care for regional films. It is an uphill, almost hopeless, battle. "Local history" and "amateur" weigh heavily in some circles as pejorative. Funding support for regional film preservation is virtually nonexistent. We believe that local and regional moving images record and interpret the real issues and real lives of the passing century. From these moving images and sound posterity will understand the era--its life and its art. James Agee wrote, "since intimate specification is even less dispensable to most good art than generalization, I believe that most of the best films, like most of the best of any other art, are and would always have to be developed locally, and primarily for local audiences." (The Nation. 24 Nov 1945). While Agee's is an extreme statement, we'll take the opportunity to stand up for these comers of the national film preservation picture: 1. There are few advocates when the production and exhibition canon is left behind. For example, so-called "our town pictures." often made by itinerant exhibitors, have next to no literature legitimizing the genre. Their valuable look into our nation's democratization of film language and technique, as well as community life, awaits discovery and preservation.