Note Spain, Gibraltar and Territorial Waters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gibraltar's Constitutional Future

RESEARCH PAPER 02/37 Gibraltar’s Constitutional 22 MAY 2002 Future “Our aims remain to agree proposals covering all outstanding issues, including those of co-operation and sovereignty. The guiding principle of those proposals is to build a secure, stable and prosperous future for Gibraltar and a modern sustainable status consistent with British and Spanish membership of the European Union and NATO. The proposals will rest on four important pillars: safeguarding Gibraltar's way of life; measures of practical co-operation underpinned by economic assistance to secure normalisation of relations with Spain and the EU; extended self-government; and sovereignty”. Peter Hain, HC Deb, 31 January 2002, c.137WH. In July 2001 the British and Spanish Governments embarked on a new round of negotiations under the auspices of the Brussels Process to resolve the sovereignty dispute over Gibraltar. They aim to reach agreement on all unresolved issues by the summer of 2002. The results will be put to a referendum in Gibraltar. The Government of Gibraltar has objected to the process and has rejected any arrangement involving shared sovereignty between Britain and Spain. Gibraltar is pressing for the right of self-determination with regard to its constitutional future. The Brussels Process covers a wide range of topics for discussion. This paper looks primarily at the sovereignty debate. It also considers how the Gibraltar issue has been dealt with at the United Nations. Vaughne Miller INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS AND DEFENCE SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: List of 15 most recent RPs 02/22 Social Indicators 10.04.02 02/23 The Patents Act 1977 (Amendment) (No. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 18 March 2009

United Nations A/AC.109/2009/15 General Assembly Distr.: General 18 March 2009 Original: English Special Committee on the Situation with regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples Gibraltar Working paper prepared by the Secretariat Contents Page I. General ....................................................................... 3 II. Constitutional, legal and political issues ............................................ 3 III. Budget ....................................................................... 5 IV. Economic conditions ............................................................ 5 A. General................................................................... 5 B. Trade .................................................................... 6 C. Banking and financial services ............................................... 6 D. Transportation, communications and utilities .................................... 7 E. Tourism .................................................................. 8 V. Social conditions ............................................................... 8 A. Labour ................................................................... 8 B. Human rights .............................................................. 9 C. Social security and welfare .................................................. 9 D. Public health .............................................................. 9 E. Education ................................................................ -

Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708

international journal of military history and historiography 39 (2019) 7-33 IJMH brill.com/ijmh Britain, Austria, and the “Burden of War” in the Western Mediterranean, 1703–1708 Caleb Karges* Concordia University Irvine, California [email protected] Abstract The Austrian and British alliance in the Western Mediterranean from 1703 to 1708 is used as a case study in the problem of getting allies to cooperate at the strategic and operational levels of war. Differing grand strategies can lead to disagreements about strategic priorities and the value of possible operations. However, poor personal rela- tions can do more to wreck an alliance than differing opinions over strategy. While good personal relations can keep an alliance operating smoothly, it is often military necessity (and the threat of grand strategic failure) that forces important compro- mises. In the case of the Western Mediterranean, it was the urgent situation created by the Allied defeat at Almanza that forced the British and Austrians to create a work- able solution. Keywords War of the Spanish Succession – Coalition Warfare – Austria – Great Britain – Mediter- ranean – Spain – Strategy * Caleb Karges obtained his MLitt and PhD in Modern History from the University of St An- drews, United Kingdom in 2010 and 2015, respectively. His PhD thesis on the Anglo-Austrian alliance during the War of the Spanish Succession received the International Commission of Military History’s “André Corvisier Prize” in 2017. He is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Concordia University Irvine in Irvine, California, usa. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/24683302-03901002Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 04:24:08PM via free access <UN> 8 Karges 1 Introduction1 There were few wars in European history before 1789 as large as the War of the Spanish Succession. -

Innovation Edition

1 Issue 36 - Summer 2019 iMindingntouch Gibraltar’s Business INNOVATION EDITION INSIDE: Hungry Monkey - Is your workplace The GFSB From zero to home inspiring Gibtelecom screen hero innovation & Innovation creativity? Awards 2019 intouch | ISSUEwww.gfsb.gi 36 | SUMMER 2019 www.gibraltarlawyers.com ISOLAS Trusted Since 1892 Property • Family • Corporate & Commercial • Taxation • Litigation • Trusts Wills & Probate • Shipping • Private Client • Wealth management • Sports law & management For further information contact: [email protected] ISOLAS LLP Portland House Glacis Road PO Box 204 Gibraltar. Tel: +350 2000 1892 Celebrating 125 years of ISOLAS CONTENTS 3 05 MEET THE BOARD 06 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD 08 HUNGRY MONKEY - FROM ZERO TO HOME SCREEN HERO 12 WHAT’S THE BIG iDEA? 14 IS YOUR WORKPLACE INSPIRING INNOVATION & CREATIVITY? 12 16 NETWORKING, ONE OF THE MAIN REASONS PEOPLE JOIN THE GFSB WHAT’S THE BIG IDEA? 18 SAVE TIME AND MONEY WITH DESKTOPS AND MEETINGS BACKED BY GOOGLE CLOUD 20 NOMNOMS: THE NEW KID ON THE DELIVERY BLOCK 24 “IT’S NOT ALL ABOUT BITCOIN”: CRYPTOCURRENCY AND DISTRIBUTED LEDGER TECHNOLOGY 26 JOINT BREAKFAST CLUB WITH THE WOMEN IN BUSINESS 16 26 NETWORKING, ONE OF THE JOINT BREAKFAST CLUB WITH 28 GFSB ANNUAL GALA DINNER 2019 MAIN REASONS PEOPLE JOIN THE WOMEN IN BUSINESS THE GFSB 32 MEET THE GIBRALTAR BUSINESS WITH A TRICK UP ITS SLEEVE 34 SHIELDMAIDENS VIRTUAL ASSISTANTS - INDEFATIGABLE ASSISTANCE AND SUPPORT FOR ALL BUSINESSES 36 ROCK RADIO REFRESHES THE AIRWAVES OVER GIBRALTAR 38 WHEN WHAT YOU NEED, NEEDS TO HAPPEN RIGHT -

1892-1929 General

HEADING RELATED YEAR EVENT VOL PAGE ABOUKIR BAY Details of HM connections 1928/112 112 ABOUKIR BAY Action of 12th March Vol 1/112 112 ABUKLEA AND ABUKRU RM with Guards Camel Regiment Vol 1/73 73 ACCIDENTS Marine killed by falling on bayonet, Chatham, 1860 1911/141 141 RMB1 marker killed by Volunteer on Plumstead ACCIDENTS Common, 1861 191286, 107 85, 107 ACCIDENTS Flying, Captain RISK, RMLI 1913/91 91 ACCIDENTS Stokes Mortar Bomb Explosion, Deal, 1918 1918/98 98 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Death of Major Oldfield Vol 1/111 111 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Turkish Medal awarded to C/Sgt W Healey 1901/122 122 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Ball at Plymouth in 1804 to commemorate 1905/126 126 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Death of a Veteran 1907/83 83 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Correspondence 1928/119 119 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Correspondence 1929/177 177 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) 1930/336 336 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Syllabus for Examination, RMLI, 1893 Vol 1/193 193 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) of Auxiliary forces to be Captains with more than 3 years Vol 3/73 73 ACTON, MIDDLESEX Ex RM as Mayor, 1923 1923/178 178 ADEN HMS Effingham in 1927 1928/32 32 See also COMMANDANT GENERAL AND GENERAL ADJUTANT GENERAL OFFICER COMMANDING of the Channel Fleet, 1800 1905/87 87 ADJUTANT GENERAL Change of title from DAGRM to ACRM, 1914 1914/33 33 ADJUTANT GENERAL Appointment of Brigadier General Mercer, 1916 1916/77 77 ADJUTANTS "An Unbroken Line" - eight RMA Adjutants, 1914 1914/60, 61 60, 61 ADMIRAL'S REGIMENT First Colonels - Correspondence from Lt. -

On Rocks and Hard Places

On Rocks And Hard Places Transforming Borders and Identities in Pre-Brexit Gibraltar Fabian Berends 4069331 Utrecht University 2nd of August 2019 A thesis submitted to the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Conflict Studies and Human Rights Supervisor: Dr. Ralph W.F.G. Sprenkels Date of Submission: 2nd of August 2019 Program Trajectory: Research and Thesis Writing only (30 ECTS) Word Count: 28896 Cover Photo: The Gibraltar-Spain border from the Spanish side. Source: author. Declaration of Originality/Plagiarism Declaration MA Thesis in Conflict Studies & Human Rights Utrecht University (course module GKMV 16028) I hereby declare: • that the content of this submission is entirely my own work, except for quotations from published and unpublished sources. These are clearly indicated and acknowledged as such, with a reference to their sources provided in the thesis text, and a full reference provided in the bibliography; • that the sources of all paraphrased texts, pictures, maps, or other illustrations not resulting from my own experimentation, observation, or data collection have been correctly referenced in the thesis, and in the bibliography; • that this Master of Arts thesis in Conflict Studies & Human Rights does not contain material from unreferenced external sources (including the work of other students, academic personnel, or professional agencies); • that this thesis, in whole or in part, has never been submitted elsewhere for academic credit; • that I have read and understood Utrecht University’s definition of plagiarism, as stated on the University’s information website on “Fraud and Plagiarism”: “Plagiarism is the appropriation of another author’s works, thoughts, or ideas and the representation of such as one’s own work.” (Emphasis added.)1 Similarly, the University of Cambridge defines “plagiarism” as “ … submitting as one's own work, irrespective of intent to deceive, that which derives in part or in its entirety from the work of others without due acknowledgement. -

The Jewish Impact on the Social and Economic Manifestation of the Gibraltarian Identity

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship 2011 The Jewish impact on the social and economic manifestation of the Gibraltarian identity Andrea Hernandez Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation Hernandez, Andrea, "The Jewish impact on the social and economic manifestation of the Gibraltarian identity" (2011). WWU Graduate School Collection. 200. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/200 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Jewish Impact on the Social and Economic Manifestation of the Gibraltarian Identity. By Andrea Hernandez Accepted in Partial Completion Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Moheb A. Ghali, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Helfgott Dr. Mariz Dr. Jimerson The Jewish Impact on the Social and Economic Manifestation of the Gibraltarian Identity. By Andrea Hernandez Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Moheb A. Ghali, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Helfgott Dr. Mariz Dr. Jimerson MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non‐exclusive royalty‐free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. -

Why the U.S. Should Back British Sovereignty Over Gibraltar Luke Coffey

BACKGROUNDER No. 2879 | FEBRUARY 13, 2014 Self-Determination and National Security: Why the U.S. Should Back British Sovereignty over Gibraltar Luke Coffey Abstract The more than three-centuries-long dispute between Spain and Key Points the United Kingdom over the status of Gibraltar has been heating up again. The U.S. has interests at stake in the dispute: It benefits n Gibraltar’s history is important, from its close relationship with Gibraltar as a British Overseas Ter- and the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht ritory. The Anglo–American Special Relationship means that the is clear that Gibraltar is British today, but most important is U.S. enjoys access to British overseas military bases unlike any other the right of the Gibraltarians to country in the world. From America’s first overseas military inter- self-determination. vention in 1801 against the Barbary States to the most recent military n Since 1801, the U.S. has ben- overseas intervention in 2011 against Qadhafi’s regime in Libya, the efited from its relationship with U.S. has often relied on Gibraltar’s military facilities. An important Gibraltar as a British Overseas part of the Gibraltar dispute between the U.K. and Spain is the right Territory in a way that would not of self-determination of the Gibraltarians—a right on which America be possible with Gibraltar under was founded, and a right that Spain regularly ignores. Spain is an Spanish control. British control of important NATO ally, and home to several U.S. military installations, Gibraltar ensures virtually guar- but its behavior has a direct impact on the effectiveness of U.S. -

As Andalusia

THE SPANISH OF ANDALUSIA Perhaps no other dialect zone of Spain has received as much attention--from scholars and in the popular press--as Andalusia. The pronunciation of Andalusian Spanish is so unmistakable as to constitute the most widely-employed dialect stereotype in literature and popular culture. Historical linguists debate the reasons for the drastic differences between Andalusian and Castilian varieties, variously attributing the dialect differentiation to Arab/Mozarab influence, repopulation from northwestern Spain, and linguistic drift. Nearly all theories of the formation of Latin American Spanish stress the heavy Andalusian contribution, most noticeable in the phonetics of Caribbean and coastal (northwestern) South American dialects, but found in more attenuated fashion throughout the Americas. The distinctive Andalusian subculture, at once joyful and mournful, but always proud of its heritage, has done much to promote the notion of andalucismo within Spain. The most extreme position is that andaluz is a regional Ibero- Romance language, similar to Leonese, Aragonese, Galician, or Catalan. Objectively, there is little to recommend this stance, since for all intents and purposes Andalusian is a phonetic accent superimposed on a pan-Castilian grammatical base, with only the expected amount of regional lexical differences. There is not a single grammatical feature (e.g. verb cojugation, use of preposition, syntactic pattern) which separates Andalusian from Castilian. At the vernacular level, Andalusian Spanish contains most of the features of castellano vulgar. The full reality of Andalusian Spanish is, inevitably, much greater than the sum of its parts, and regardless of the indisputable genealogical ties between andaluz and castellano, Andalusian speech deserves study as one of the most striking forms of Peninsular Spanish expression. -

Multiculturalism in the Creation of a Gibraltarian Identity

canessa 6 13/07/2018 15:33 Page 102 Chapter Four ‘An Example to the World!’: Multiculturalism in the Creation of a Gibraltarian Identity Luis Martínez, Andrew Canessa and Giacomo Orsini Ethnicity is an essential concept to explain how national identities are articulated in the modern world. Although all countries are ethnically diverse, nation-formation often tends to structure around discourses of a core ethnic group and a hegemonic language.1 Nationalists invent a dominant – and usually essentialised – narrative of the nation, which often set aside the languages, ethnicities, and religious beliefs of minori- ties inhabiting the nation-state’s territory.2 In the last two centuries, many nation-building processes have excluded, removed or segregated ethnic groups from the national narrative and access to rights – even when they constituted the majority of the population as in Bolivia.3 On other occasions, the hosting state assimilated immigrants and ethnic minorities, as they adopted the core-group culture and way of life. This was the case of many immigrant groups in the USA, where, in the 1910s and 1920s, assimilation policies were implemented to acculturate minorities, ‘in attempting to win the immigrant to American ways’.4 In the 1960s, however, the model of a nation-state as being based on a single ethnic group gave way to a model that recognised cultural diver- sity within a national territory. The civil rights movements changed the politics of nation-formation, and many governments developed strate- gies to accommodate those secondary cultures in the nation-state. Multiculturalism is what many poly-ethnic communities – such as, for instance, Canada and Australia – used to redefine their national identi- ties through the recognition of internal cultural difference. -

An Ottoman Merchant in the Gibraltar Vice-Admiralty Court in the 1760S

WHEN PROOF IS NOT ENOUGH AN OTTOMAN MERCHANT IN THE GIBRALTAR VICE-ADMIRALTY COURT IN THE 1760S This article examines the litigation of an Ottoman merchant based in Algiers in the vice-admiralty court of Algiers in 1760. It examines the impor- tance of legal proofs for merchants traversing the Mediterranean world, and the ability of such merchants to record transactions and interactions along the way, as well as to subsequently call on witnesses from near and far. The case examined here sees documents compiled in Italian, Spanish, Arabic, and English, constructing a solid legal case, which was rejected by the British on the grounds of setting a precedent and privileging a «Moor» over a British subject. This then raises the question of the validity of proofs in different Mediterranean settings, with the Ottoman merchant’s diverse and thorough documentation rejected in Gibraltar when it would have been entirely ad- missible in another legal setting. Keywords: Commercial litigation, Algiers, Gibraltar, legal proofs. xIntroduction The study of merchants often centres on the disputes in which they found themselves; after all, problems generate paperwork. The early modern Mediterranean, a mix of different languages, cultures, polit- ies, and legal systems, generated plenty of legal disagreements between merchants from a variety of backgrounds. This article aims to explore what happened to an Ottoman subject based in Algiers when things went wrong for him in the Western Mediterranean, and who sought re- dress in the British vice-admiralty court of Gibraltar. It is an exceptional case in many ways, but indicative of a growing number of unsuccess- ful litigations of North African and Ottoman merchants in European courts, particularly in the second half of the eighteenth century. -

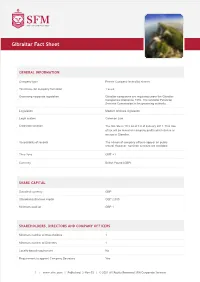

Gibraltar Fact Sheet

SFM CORPORATE FACT SHEET Gibraltar Fact Sheet GENERAL INFORMATION Company type Private Company limited by shares Timeframe for company formation 1 week Governing corporate legislation Gibraltar companies are regulated under the Gibraltar Companies Ordinance 1930. The Gibraltar Financial Services Commission is the governing authority. Legislation Modern offshore legislation Legal system Common Law Corporate taxation The tax rate is 10% as of 1st of January 2011. This rate of tax will be levied on company profits which derive or accrue in Gibraltar. Accessibility of records The names of company officers appear on public record. However, nominee services are available. Time zone GMT +1 Currency British Pound (GBP) SHARE CAPITAL Standard currency GBP Standard authorised capital GBP 2,000 Minimum paid up GBP 1 SHAREHOLDERS, DIRECTORS AND COMPANY OFFICERS Minimum number of Shareholders 1 Minimum number of Directors 1 Locally-based requirement No Requirement to appoint Company Secretary Yes 1 | www.sfm.com | Published: 2-Nov-15 | © 2021 All Rights Reserved SFM Corporate Services Gibraltar Fact Sheet SFM CORPORATE FACT SHEET ACCOUNTING REQUIREMENTS Requirement to prepare accounts Yes Requirement to appoint auditor Yes Requirement to file accounts Yes Accessibility of accounts None Requirement to file annual return Yes DOCUMENT REQUIREMENTS Certified copy of valid passport (or national identity card) Certified copy of 2 proofs of address (issued within the last 3 months) in English or translated into English One original professional reference One original bank reference Details of source of income CV INCORPORATION FEES Initial set-up and- first year EUR 2950 Per year from second year EUR 2100 GOOD TO KNOW In Gibraltar there is no capital gains tax, wealth tax, sales tax, Estate duty, or value added tax and Non-Resident companies can take advantage of a number of offshore regimes.