From Hierarchy to Networks – and Back Again?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fylkesmannens Kommunebilde Evje Og Hornnes Kommune 2013

Fylkesmannens kommunebilde Evje og Hornnes kommune 2013 Innhold 1 Innledning 3 2 Planlegging og styring av kommunen 4 2.1 Demografi 4 2.2 Likestilling 5 2.3 Økonomi og økonomistyring 8 2.4 Bosetting og kvalifisering av flyktninger 12 3 Tjenesteyting og velferdsproduksjon 14 3.1 Barnehage 14 3.2 Tidlig innsats 18 3.3 Utdanning 19 3.4 Vergemål 25 3.5 Byggesak 26 3.6 Folkehelse og levekår 27 3.7 Barneverntjenesten 29 3.8 Helsesøster- og jordmortjeneste 32 3.9 Helsetjenester 33 3.10 Tjenester i sykehjem 35 3.11 Velferdsprofil 37 3.12 Arealplanlegging 39 3.13 Forurensning 40 3.14 Landbruk 41 Side: 2 - Fylkesmannen i Aust-Agder, kommunebilde 2013 Evje og Hornnes 1 Innledning Kommunebilde, som Fylkesmannen utarbeider for alle 15 kommuner i Aust-Agder, er et viktig element i styringsdialogen mellom kommunene og Fylkesmannen. Det gir ikke et fullstendig utfyllende bilde av kommunens virksomhet, men gjelder de felt der Fylkesmannen har oppdrag og dialog mot kommunene. Det er et dokument som peker på utfordringer og handlingsrom. Fylkesmannen er opptatt av at kommunene kan løse sine oppgaver best mulig og ha politisk og administrativt handlingsrom. Det er viktig at kommunene har et best mulig beslutningsgrunnlag for de valg de tar. Blant annet derfor er kommunebilde et viktig dokument. Kommunebilde er inndelt i tre 1. Innledning 2. Planlegging og styring av kommunen 3. Tjenesteyting og velferdsproduksjon Under hvert punkt har vi oppsummert Fylkesmannens vurdering av utfordringspunkter for kommunen. Dette er punkter vi anbefaler kommunen å legge til grunn i videre kommunalplanlegging. Kommunebilde er et godt utgangspunkt for å få et makrobilde av kommunen og bør brukes aktivt i kommunen – ikke minst av de folkevalgte. -

Søknad Solhom

Konsesjonssøknad Solhom - Arendal Spenningsoppgradering Søknad om konsesjon for ombygging fra 300 til 420 kV 1 Desember 2012 Forord Statnett SF legger med dette frem søknad om konsesjon, ekspropriasjonstillatelse og forhånds- tiltredelse for spenningsoppgradering (ombygging) av eksisterende 300 kV-ledning fra Arendal transformatorstasjon i Froland kommune til Solhom kraftstasjon i Kvinesdal kommune. Ledningen vil etter ombyggingen kunne drives med 420 kV spenning. Spenningsoppgraderingen og tilhørende anlegg vil berøre Froland, Birkenes og Evje og Hornnes kommuner i Aust-Agder og Åseral og Kvinesdal kommuner i Vest-Agder. Oppgraderingen av 300 kV- ledningen til 420 kV på strekningen Solhom – Arendal er en del av det større prosjektet ”Spennings- oppgraderinger i Vestre korridor” og skal legge til rett for sikker drift av nettet på Sørlandet, ny fornybar kraftproduksjon, fri utnyttelse av kapasiteten på nye og eksisterende mellomlandsforbindelser og fleksibilitet for fremtidig utvikling. Konsesjonssøknaden oversendes Norges vassdrags- og energidirektorat (NVE) til behandling. Høringsuttalelser sendes til: Norges vassdrags- og energidirektorat Postboks 5091, Majorstuen 0301 OSLO e-post: [email protected] Saksbehandler: Kristian Marcussen, tlf: 22 95 91 86 Spørsmål vedrørende søknad kan rettes til: Funksjon/stilling Navn Tlf. nr. Mobil e-post Delprosjektleder Tor Morten Sneve 23903015 40065033 [email protected] Grunneierkontakt Ole Øystein Lunde 23904121 99044815 [email protected] Relevante dokumenter og informasjon om prosjektet og Statnett finnes på Internettadressen: http://www.statnett.no/no/Prosjekter/Vestre-korridor/Solhom---Arendal/ Oslo, desember 2012 Håkon Borgen Konserndirektør Divisjon Nettutbygging 2 Sammendrag Statnett er i gang med å bygge neste generasjon sentralnett. Dette vil bedre forsyningssikkerheten og øke kapasiteten i nettet, slik at det legges til rette for mer klimavennlige løsninger og økt verdiskaping for brukerne av kraftnettet. -

Utdanningsplan for Leger I Spesialisering I Nyresykdommer Ved Sørlandet Sykehus

Utdanningsplan for leger i spesialisering i nyresykdommer ved Sørlandet Sykehus Om utdanningsvirksomheten Sørlandet sykehus er Agders største kompetansebedrift, med over 7000 ansatte fordelt på ulike lokasjoner. SSHF har ansvar for spesialisthelsetjenester innen fysisk og psykisk helse og avhengighetsbehandling. Sykehusene ligger i Arendal, Kristiansand og Flekkefjord. I tillegg har vi distriktspsykiatriske sentre og poliklinikker flere andre steder i Agder. I fjor var det over 550 000 pasientbehandlinger i Sørlandet sykehus. Om organisering av spesialiteten Nyremedisinsk virksomhet er organisert som seksjoner i medisinsk avdeling både i Arendal og Kristiansand. Ved begge avdelinger er det egen dialyseavdeling. Det behandles også mange nyrepasienter i Flekkefjord i den generelle indremedisinske avdelingen der som også har egen dialyseavdeling. Ved behov for nyremedisinsk kompetanse konsulteres nyrelegene i Kristiansand eller pasientene overflyttes dit. De nyremedisinske pasientene håndteres poliklinisk av nyremedisinerne i Kristiansand som også besøker dialysen i Flekkefjord 1 gang pr mnd. Generelle indremedisinske læringsmål i del 2 indremedisin dekkes alle tre steder, men de fleste læringsmålene i del 3 nyremedisin må dekkes i Arendal eller Kristiansand. LIS 3 i nyremedisin ved SSHF skal rotere i 6 mnd til Ullevål eller AHUS og 3 mnd til Rikshospitalet for å nå læringsmål i transplantasjonsmedisin. Om avdelingen/seksjonen i SSHF Medisinsk avdeling ligger under somatisk klinikk delt ved tre lokalisasjoner, Flekkefjord, Arendal og Kristiansand. Det er egne nyremedisinske seksjoner i Arendal og Kristiansand, mens i Flekkefjord ligger nyrepasientene i generell medisinsk avdeling ved innleggelse. Nyreseksjonen i Arendal har 6 senger som deles mellom hema/endo/nefro. Det er 3 overleger i nyremedisin som jobber ved avdelingen. Nyreseksjonen i Kristiansand har 4 senger. -

Geochronology of the Gloserheia Pegmatite, Froland, Southem Norway

Geochronology of the Gloserheia pegmatite, Froland, southem Norway HALFDAN BAADSGAARD, CATHERINE CHAPLIN & WILLIAM L. GRIFFIN Baadsgaard, H., Chaplin, C. & Griffin, W. L.: Geochronology of the Gloserheia pegmatite, Froland, southem Norway. Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, Vol. 64, pp. 111-119. Oslo 1984. ISSN 0029-196X. Relatively unaltered feldspars from the Gloserheia pegmatite yield an Rb-Sr isochron age of 1062± 11 Ma(M.S.W.D. = 90, Sr1 = 0.7023 ± 0.0002) and a Pb-Pb isochron age of 1085±28 Ma. The best age of pegmatite crystallization is given by a U-Pb concordia-discordia intersection at 1060�: Ma from euxenite samples. The radiometric ages limit the last major metamorphism in the area to > 1060 Ma, although mild later hydration has reset Rb-Sr mineral dates on muscovite and biotite to as low as -850 Ma. O, Sr and Pb isotope data indicate that the pegmatite magma was derived from a mantle source. Halfdan Baadsgaard, Dept. of Geology University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada. Catherine Chaplin, Dept. of Geology University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada. William L. Griffin, Mineralogisk-Geologisk Museum, Sarsgt. l, Oslo 5, Norway. Complex pegmatites containing unusual minerals phosed to upper amphibolite - intermediate-P are recognized to possess very suitable material granulite facies. Foliations in the country rocks for radiometric dating. Pegmatitic uraninite hav are sharply crosscut by the pegmatite, indicating ing concordant U-Th-Pb ages was used to 'geo that the pegmatite is post-tectonic with regard to logically' determine both the decay constant of the last major metamorphic episode in the area. 40K (to 40Ar) (Wetherill et al. -

Årsrapport 2019 Årsberetning

Respekt, faglig dyktighet, tilgjengelighet og engasjement Flekkefjord Kristiansand Arendal Årsrapport 201 20149 Sørlandet sykehus HF - trygghet når du trenger det mest Innholdsfortegnelse Årsberetning 3 Resultatregnskap 13 Balanse 14 Kontantstrømoppstilling 15 Noter 16 Revisors beretning 32 2 Sørlandet sykehus HF Årsrapport 2019 Årsberetning Dette er Sørlandet sykehus gevinstrealisering i prosjektene. Bedre kvalitet i Sørlandet sykehus HF (SSHF) eies av det regionale pasientbehandlingen skal sikres gjennom arbeid med helseforetaket Helse Sør-Øst RHF. SSHF leverer helhetlige pasientforløp gjennom alle tjenesteledd. spesialisthelsetjenester til i overkant av 300 000 Arbeidet skal være kunnskapsbasert, og inkludere mennesker i sykehusområdet. Agder er primært forpliktende samhandling basert på avtaler med opptaksområde. I tillegg har SSHF regionale og kommunehelsetjenesten. nasjonale funksjoner. Programmet startet 01.03.2019 og det er satt i gang en SSHFs lovpålagte oppgaver er pasientbehandling, rekke prosjekter som følges opp fra programkontoret. forskning, utdanning av helsepersonell samt opplæring av pasienter og pårørende. Ansvarsområdene omfatter Hovedmål somatikk, psykisk helsevern, tverrfaglig spesialisert SSHF skal gi befolkningen i Agder tilgang til spesialist- rusbehandling, spesialisert rehabilitering, prehospitale helsetjenester slik dette er fastsatt i lover og forskrifter. tjenester og pasientreiser. SSHF skal innrette sin virksomhet med sikte på å nå følgende hovedmål gitt av Helse Sør-Øst RHF i Oppdrag SSHF har somatiske sykehus i Arendal, Kristiansand og bestilling 2019: og Flekkefjord. Psykiatrisk sykehusavdeling er lokalisert i Arendal og Kristiansand. Distrikts- 1. Redusere unødvendig venting og variasjon i psykiatriske og barne- og ungdomspsykiatriske enheter kapasitetsutnyttelsen ligger i kommunene Kristiansand, Mandal, Kvinesdal, 2. Prioritere psykisk helsevern og tverrfaglig Farsund, Flekkefjord, Arendal, Lillesand, Grimstad og spesialisert rusbehandling Tvedestrand. Det er polikliniske og døgnbaserte enheter innen rusbehandling i begge 3. -

01 Agder Kommunesammenslåing

Veien til færre og større Agder-kommuner Her er oversikt over status på prosessene SIRDAL: Ønsker primært å stå alene. Er også involvert i VEST-AGDER rundt kommunesammenslåing i alle mulighetsstudiet «Langfjella» (Sirdal, Valle, Bykle, Vinje, og Bygland), men har satt det på vent. 180 877 innbyggere AUST-AGDER kommunene i Agder-fylkene. ÅSERAL: Kommunestyret vedtok 25. juni med 9 mot 8 stemmer å stå alene. Alternativene er 114 767 innbyggere «Midtre Agder» og «Indre Agder» (Åseral, Bygland, Evje og Hornnes) Saken skal opp 1838 BYKLE 933 ÅMLI: SIRDAL Kommunestyret takket igjen 3. september, og det skal holdes BYKLE: rådgivende folkeavstemning 14. september. Kommunestyret vedtok 25. juni å 18. juni ja til videre UTSNITT utrede «nullalternativet». De vil sonderinger med også utrede sammenslåing med Froland. Takket også ja KVINESDAL: til sonderinger med ÅSERAL 925 Valle og Bygland i «Setesdal»- Foreløpig uklar situasjon, sak framlegges for alternativet, og ønsker drøftinger Nissedal i Telemark. formannskapet 1. september. Opprinnelig om aktuelle samarbeidsområder med i «Lister 5» som har strandet, «Lister 3» med Vinje og Sirdal. vil muligens bli vurdert. Men ønsker også VEGÅRSHEI: GJERSTAD: RISØR: 5948 Sirdal med på laget. KVINESDAL VALLE 1251 Kommunestyret vedtok Ønsker å gå videre med Bystyret oppfordret 28. mai de 16. juni at de er best «Østregionen» (Gjerstad, fire kommunene i «Østregionen» VALLE: tjent med å stå alene, Vegårdshei, Tvedestrand å utrede sammenslåing. HÆGEBOSTAD: Formannskapet vedtok 24. juni å Kommunestyret sa 18. juni ja til å forhandle både men vil også vurdere og Risør). Vurderer også Arbeidet med Østre Agder går utrede «nullaltenativet», altså å stå «Østre Agder» og om Åmli bør være med, parallelt, og kommunestyret om «Midtre Agder» (Marnardal, Audnedal, alene. -

Sluttrapport Fra Forvaltningskontroll Landbruk Evje Og Hornnes Og Iveland

Landbruksavdelingen Sluttrapport fra kontroll av forvaltningen av utvalgte tilskuddsordninger i landbruket – 2016 Kontrollert Evje og Hornnes og Iveland Kontrollpersoner fra Hans Bach- enhet kommuner Fylkesmannen i Evensen og Rolf Aust- og Vest-Agder Inge Pettersen Kontrollomfang Dato for sluttrapport 01.12.2016 -Avløsning ved sykdom og fødsel mv. - Tilskudd til spesielle miljøtiltak i landbruket (SMIL). Kommune Kontaktperson Evje og Hornnes og Iveland kommune Inge Eftevand Rapportens innhold Rapporten er utarbeidet etter gjennomført forvaltningskontroll i Iveland og Evje og Hornnes kommune innen ordningene med avløsning ved sykdom og fødsel mv. og tilskudd til spesielle miljøtiltak i landbruket (SMIL). Rapporten er utarbeidet som 1 rapport til begge kommunene siden det er felles forvaltning på de aktuelle landbrukstilskuddene. Den beskriver eventuelle avvik og merknader som ble avdekket innen de kontrollerte områdene. Avvik er mangel på oppfyllelse av krav fastsatt i lov, forskrift og/eller rundskriv. Merknad er forhold som ikke er i strid med krav, men der Fylkesmannen finner grunn til å påpeke behov for forbedring. Bakgrunn for kontrollen Fylkesmannen har det regionale ansvar for å sikre at statlige midler brukes og forvaltes i samsvar med forutsetningene. Forvaltningskontrollen har hjemmelsgrunnlag i Økonomireglementet i staten (§ 15) og bakgrunn i fullmaktsbrev fra Landbruksdirektoratet for 2016. Ved å avdekke eventuelle avvik og brudd på regelverk og rutiner vil dette kunne hjelpe kommunen fram mot en sikrere, bedre og mer effektiv forvaltning av tilskuddsordningene. Gjennomføring og omfang Kontrollen ble gjennomført som en dokumentkontroll. Fylkesmannen gjennomgikk forhåndsvalgte saker som kommunene hadde oversendt. Dette gjaldt 3 saker om tilskudd til avløsning til sykdom og fødsel mv. og 4 saker tilknyttet SMIL ordningen. -

Lokale Energiutredninger for Kommunene I Østre Agder

Lokal energiutredning for Birkenes kommune 25/4-2012 Rolf Erlend Grundt, Agder Energi Nett Gunn Spikkeland Hansen, Rejlers Lokal energiutredning, målsetting • Forskrifter: – Forskrift om energiutredninger. (2002-12-16) – Endr. i forskrifter til energiloven. (2006-12-14) – Endr. i forskrift om energiutredninger. (2008-06- 02) • Øke kunnskapen om lokal energiforsyning, stasjonær energibruk og alternativer på dette området. • Dette for å få mer varierte energiløsninger i kommunen, og slik bidra til en samfunnsmessig rasjonell utvikling av energisystemene. • Oppdateres hvert annet år AEN ønsker også å få nytte av LEU • Oversikt over kjente utbyggingsplaner i kommunene på større tiltak til fritidsboliger, husholdninger, tjenesteyting, industri Oppdateres årlig – dette er 6. gang • Planer i kommunene der elektrisk forbruk til vann- eller romoppvarming skal erstattes av andre energibærere Gir det utslag på dimensjoneringen av nettet? Leveringspålitelighet 10 20 9 18 8 16 7 14 6 12 5 10 Birkenes 4 8 Aust-Agder 3 6 2 4 Antall perAntall rapporteringspunkt perTimer rapporteringspunkt 1 2 0 0 2007 2008 2009 2010 2007 2008 2009 2010 Gjennomsnittlig antall avbrudd Varighet på avbrudd Utførte tiltak siste to år Etablering av reserveforbindelser i Birkeland sentrum (Hauane - Valstrand). Skiftet utstyr i Birkeland TS for bedre overvåking av nettet. Kommende tiltak Fornye koblingsanlegg til Glassfiberen (3B) og etablere fjernstyring. Dette vil redusere utkoblingstid ved feil. Utføres september 2012, samarbeid med 3B. Agder Energi Nett søkte høsten 2011 om bygging av ny Vegusdal transformatorstasjon i Birkenes kommune. Gitt at konsesjon gis er stasjonen planlagt bygd imellom 2012 og 2014. Stasjonen vil blant annet legge til rette for småkraft og forbedre leveringspåliteligheten i deler av Iveland, Åmli, Froland, Birkenes og Evje- og Hornnes kommune. -

Sparebanken Sør Boligkreditt AS

Sparebanken Sør Boligkreditt AS Investor Presentation March 2016 Executive summary . The fifth largest savings bank in Norway with a strong market position in Southern Norway . High capitalization; Capital ratio of 15.5 % - Core Tier 1 ratio of 12.7 % at December 31th 2015 Sparebanken Sør . Rated A1 (stable outlook) by Moody’s . Strong asset quality – 65 per cent of loan book to retail customers . New rights issue of NOK 600 million in progress will strengthen capital ratio even further . 100 % owned and dedicated covered bond subsidiary of Sparebanken Sør . Cover pool consisting of 100 % prime Norwegian residential mortgages Sparebanken Sør . High quality cover pool reflected by the weighted average LTV of 55.3 % Boligkreditt . Covered bonds rated Aaa by Moody’s with 5 notches of “leeway” . Strong legal framework for covered bonds in Norway with LTV limit of 75 % for residential mortgages . Low interest rates, weak NOK and fiscal stimulus are counterbalancing economic slowdown stemming from the lower oil investments . Unemployment is expected to increase gradually but from a very low level and the unemployment Norwegian rate remains well below the European levels economy . The Norwegian government has a strong financial position with large budget surplus. The government pension fund, which accounts over 200% of the GDP, provides the government with substantial economic leeway . The Southern region is clearly less exposed to oil production than Western Norway Southern region . Registered unemployment in the Southern region remains below -

Municipality Accounts 2001-2005

Official Statistics of Norway D 369 Municipality Accounts 2001-2005 Statistisk sentralbyrå • Statistics Norway Oslo–Kongsvinger Official Statitics of Norway This series consists mainly of primary statistics, statistics from statistical accounting systems and results of special censuses and surveys. The series is intended to serve reference and documentation purposes. The presentation is basically in the form of tables, figures and necessary information about data, collection and processing methods, in addition to concepts and definitions. A short overview of the main results is also included The series also includes the publications Statistical Yearbook of Norway and Svalbard Statistics © Statistics Norway, Febryary 2007 Symbols in tables Symbol By use of material from this publication, Category not applicable . please give Statistics Norway as sorurce. Data not available .. Data not yet available ... ISBN 978-82-537-7145-8 Printed version Not for publication : ISBN 978-82-537-7146-5 Elektronic version Nil - ISSN Less than 0.5 of unit employed 0 Less than 0.05 of unitemployed 0,0 Topic Provisional or preliminary figure * Break in the homogeneity of a vertical 12.01.20 series — Break in the homogeneity of a horizontal series | Print: Statistics Norway Decimal punctuation mark , Official Statistics of Norway Municipality Accounts 2001-2005 Preface The main purpose of these statistics is to present key figures and the economic situation is in the municipalities and county municipalities of Norway. This publication is based on yearly municipal and county municipal accounts from 2001-2005, which are the first five years all municipals are represented in the KOSTRA (Municipality-State-Reporting) publication. All the statistics in this publication have been published earlier I in different connections. -

Petrology of the Grimstad Granite

NORSK GEOLOGISK TIDSSKRIFT 45 PETROLOGY OF THE GRIMSTAD GRANITE I. Pro�ress Report 1964 BY J. B. OLAV H. CHRISTIE, TORGEIR FALKUM, IVAR RAMBERG and THORESEN KARI (Mineralogisk-Geologisk Museum, Sars gate l, Oslo 5) Abstract. From chemical data and field observations it is concluded that the Precambrian Grimstad granite moved upwards in the crust by the action of chemical attack and buoyancy. Assimilation of overlying rocks led to the formation of different sub-types of the granite. The red, coarse-grained Grimstad microcline granite is situated in the Precambrian of the South Coast of Norway, 300 km southwest of Oslo. I. (1938, 1945), referring to the sharp granite contacfs OFTEDAL and the occurrence of some intrusion breccias near the borders, con sidered the Grimstad granite to be magmatic. J. W. BuG E (1940) A. G objected to Oftedal's suggestion that dark granite types inside the intrusive body represent earlier stages of crystalline differentiation, he maintained that the dark granite types were remnants of amphibolites assimilated by the granite. K. S. HEIER (1962, Fig. 2) gave diagrams of K, Rb, BafRb, and K/Rb of K-feldspars of a series of seven samples taken at the main road traversing the Grimstad granite. Heier's dia grams may be taken as a support of a magmatic viewpoint and an indication of concentric chemical structures in the granite body. For the present study nearly 300 samples of the Grimstad granite were collected, about 180 of them serve as the basis for a scheduled partial trend surface analysis (Fig. 1), and the following statements can be made from the data on hand at the end of 1964. -

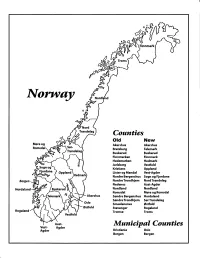

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \.