Lumbee Indians of North Carolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocanahowan and Recently Discovered Linguistic

2 OCANAHOWAN AND RECENTLY DISCOVERED LINGUISTIC FRAGMENTS FROM SOUTHERN VIRGINIA, C. 1650 Philip Barbour Ridgefield, Connecticut Published in: Papers of the 7th Algonquian Conference (1975) Ocanahowan (or Ocanahonan and other spellings) was the name of an Indian town or village, region or tribe, which was first reported in Captain John Smith's True Relation in 1608 and vanished from the records after Smith mentioned it for the last time 1624, until it turned up again in a few handwritten lines in the back of a book. Briefly, these lines cover half a page of a small quarto, and have been ascribed to the period from about 1650 to perhaps the end of the century, on the basis of style of writing. The page in question is the blank verso of the last page in a copy of Robert Johnson's Nova Britannia, published in London in 1604, now in the possession of a distinguished bibliophile of Williamsburg, Virginia. When I first heard about it, I was in London doing research and brushing up on the English language, Easter-time 1974, and Bernard Quaritch, Ltd., got in touch with me about "some rather meaningless annotations" in a small volume they had for sale. Very briefly put, for I shall return to the matter in a few minutes, I saw that the notes were of the time of the Jamestown colony and that they contained a few Powhatan words. Now that the volume has a new owner, and I have his permission to xerox and talk about it, I can explain why it aroused my interest to such an extent. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Hclassification

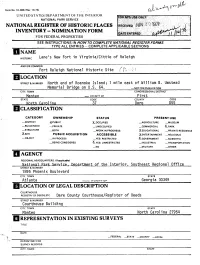

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) J, UN1TEDSTATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS___________ | NAME HISTORIC Lane's New Fort in Virginia/Cittie of Raleigh AND/OR COMMON ~ Fort Raleigh National Historic Site ( \\ ^f I____________ LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER North end of Roanoke Island; 1 mile east of William B. Umstead Memorial Bridge on U.S. 64. —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Manteo — VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE North Carolina 37 Dare 055 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT ^.PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL 2L.PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -^.EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE XsiTE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE JCENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS —YES. RESTRICTED X.GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) National Park Service. Department of the Interior, Southeast Regional Office STREET 8» NUMBER 1895 Phoenix Boulevard CITY. TOWN STATE Atlanta VICINITY OF Georgia 30349 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Dare County Courthouse/Register of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Courthouse Building CITY, TOWN STATE Manteo North Carolina 27954 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —XEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS JCALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The boundaries of Fort Raleigh National Historic Site include 159 acres. However, most of this acreage is either developed area, being managed as a natural area or the Elizabethan Gardens maintained by the Garden Club of North Carolina. -

Tar Heel Junior Historian

by Sandra Boyd* More than four hundred years ago, and children. Also aboard were two Indians, Europeans wanted to set up Manteo and Wanchese, who had gone to colonies in the New World. For England with Raleigh's previous expedition them, the New World meant the present- and were returning to their home. The pilot day continents of North was a Spaniard, Simon Fernando, and the and South America. What challenging times those must have been! Sir Walter Raleigh, an adventurous English gentleman, sent a group of men to explore the New World. A later expedition established a settlement on Roanoke Island, on the North Carolina coast. In 1586, after enduring winter hardships, lack of food, and disagreements with the Indians, survivors of this colony returned home to England with Sir Francis Drake. Then Raleigh decided to send a second group of colonists. On The baptism of Virginia Dare. April 26,1587, a small fleet set sail from England, hoping to establish governor of the new colony was John White. the first permanent English settlement in the Among the colonists were Governor White's New World. daughter, Eleanor, and her husband, This second group of colonists differed Ananias Dare. The voyage took longer than from the first because it included not only the usual six weeks, and the ships finally men but also women and children. It would anchored off Roanoke Island on July 22. be a permanent colony. The little fleet Once the colonists landed, they began consisted of the ship Lyon, a flyboat (a fast, repairing the houses already there and flat-bottomed boat capable of maneuvering started building new homes. -

Manteo Harbor Report

A CULTURAL RESOURCE EVALUATION OF SUBMERGED LANDS AFFECTED BY THE 400TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION Manteo, North Carolina Conducted By Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources Richard W. Lawrence, Head Leslie S. Bright Mark Wilde-Ramsing Report Prepared by Mark Wilde-Ramsing November, 1983 Abstract Field investigations of the submerged bottom lands at Manteo, North Carolina were carried out by the Underwater Archaeology Branch, Division of Archives and History, Department of Cultural Resources. The purpose of these investigations was to identify historically and/or archaeologically significant cultural materials lying within the area to be affected by construction of a bridge and canal system and berthing area proposed for the 400th Anniversary Celebration (1984 to 1987) on Roanoke Island. Initially, a systematic survey of the project area was performed using a proton precession magnetometer to isolate magnetic disturbances, any of which might be generated by cultural material. Following this, a diving and probing search was conducted on isolated magnetic targets to determine the source. With the exception of the remains of a sunken vessel, Underwater Site #0001ROS, all magnetic disturbances were attributed to cultural debris of recent origin (twentieth century) and were determined historically and archaeologically insignificant. Recommendations for the sunken vessel located on the south side of the proposed berthing area are (1) complete avoidance of the site during construction activities, or (2) further -

The Devil in Virginia: Fear in Colonial Jamestown, 1607-1622

The Devil in Virginia: Fear in Colonial Jamestown, 1607-1622 Matthew John Sparacio Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Crandall A. Shifflett, Chair A. Roger Ekirch Brett L. Shadle 16 March 2010 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Early Modern England; Colonial Virginia; Jamestown; Devil; Fear Copyright 2010, Matthew John Sparacio The Devil in Virginia: Fear in Colonial Jamestown, 1607-1622 Matthew John Sparacio ABSTRACT This study examines the role of emotions – specifically fear – in the development and early stages of settlement at Jamestown. More so than any other factor, the Protestant belief system transplanted by the first settlers to Virginia helps explain the hardships the English encountered in the New World, as well as influencing English perceptions of self and other. Out of this transplanted Protestantism emerged a discourse of fear that revolved around the agency of the Devil in the temporal world. Reformed beliefs of the Devil identified domestic English Catholics and English imperial rivals from Iberia as agents of the diabolical. These fears travelled to Virginia, where the English quickly ʻsatanizedʼ another group, the Virginia Algonquians, based upon misperceptions of native religious and cultural practices. I argue that English belief in the diabolic nature of the Native Americans played a significant role during the “starving time” winter of 1609-1610. In addition to the acknowledged agency of the Devil, Reformed belief recognized the existence of providential actions based upon continued adherence to the Englishʼs nationally perceived covenant with the Almighty. -

US History- Sweeney

©Java Stitch Creations, 2015 Part 1: The Roanoke Colony-Background Information What is now known as the lost Roanoke Colony, was actually the third English attempt at colonizing the eastern shores of the United States. Following through with his family's thirst for exploration, Queen Elizabeth I of England granted Sir Walter Raleigh a royal charter in 1584. This charter gave him seven years to establish a settlement, and allowed him the power to explore, colonize and rnle, in return for one-fifth of all the gold and silver mined in the new lands. Raleigh immediately hired navigators Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe to head an expedition to the intended destination of the Chesapeake Bay area. This area was sought due to it being far from the Spanish-dominated Florida colonies, and it had milder weather than the more northern regions. In July of that year, they landed on Roanoke Island. They explored the area, made contact with Native Americans, and then sailed back to England to prove their findings to Sir Walter Raleigh. Also sailing from Roanoke were two members oflocal tribes of Native Americans, Manteo (son of a Croatoan) and Wanchese (a Roanoke). Amadas' and Barlowe's positive report, and Native American assistance, earned the blessing of Sir Walter Raleigh to establish a colony. In 1585, a second expedition of seven ships of colonists and supplies, were sent to Roanoke. The settlement was somewhat successful, however, they had poor relations with the local Native Americans and repeatedly experienced food shortages. Only a year after arriving, most of the colonists left. -

Defining the Greater York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape

Defining the Greater York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape Prepared by: Scott M. Strickland Julia A. King Martha McCartney with contributions from: The Pamunkey Indian Tribe The Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe The Mattaponi Indian Tribe Prepared for: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay & Colonial National Historical Park The Chesapeake Conservancy Annapolis, Maryland The Pamunkey Indian Tribe Pamunkey Reservation, King William, Virginia The Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribe Adamstown, King William, Virginia The Mattaponi Indian Tribe Mattaponi Reservation, King William, Virginia St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland October 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As part of its management of the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail, the National Park Service (NPS) commissioned this project in an effort to identify and represent the York River Indigenous Cultural Landscape. The work was undertaken by St. Mary’s College of Maryland in close coordination with NPS. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept represents “the context of the American Indian peoples in the Chesapeake Bay and their interaction with the landscape.” Identifying ICLs is important for raising public awareness about the many tribal communities that have lived in the Chesapeake Bay region for thousands of years and continue to live in their ancestral homeland. ICLs are important for land conservation, public access to, and preservation of the Chesapeake Bay. The three tribes, including the state- and Federally-recognized Pamunkey and Upper Mattaponi tribes and the state-recognized Mattaponi tribe, who are today centered in their ancestral homeland in the Pamunkey and Mattaponi river watersheds, were engaged as part of this project. The Pamunkey and Upper Mattaponi tribes participated in meetings and driving tours. -

{PDF} Searching for Virginia Dare : on the Trail of the Lost Colony Of

SEARCHING FOR VIRGINIA DARE : ON THE TRAIL OF THE LOST COLONY OF ROANOKE ISLAND PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marjorie Hudson | 214 pages | 25 May 2013 | Press 53 | 9781935708872 | English | Winston-Salem, NC, United States Searching for Virginia Dare : On the Trail of the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island PDF Book In the English settled Jamestown, Virginia. While visiting the Outer Banks, vacationers with an appreciation of national history, or who simply love a good mystery, will find plenty of options for discovering more about Virginia Dare. Wyoming, Minnesota 3 contributions. There were no signs of a struggle or of the colonists leaving in haste. Tim marked it as to-read Dec 18, Enlarge cover. Early in the 20th century a visiting anthropologist identified a group of people called the Machapunga living on the mainland. The fact that it was placed beneath the portraits of three Confederate Generals did not help either! The mystery of what happened to the colonists remains to this day. Lawrence River. Learning More about Virginia Dare While visiting the Outer Banks, vacationers with an appreciation of national history, or who simply love a good mystery, will find plenty of options for discovering more about Virginia Dare. White desperately wanted to reach Croatoan, a mere 50 miles to the south—though he also mentions that the colonists originally intended to move 50 miles inland. The first settlement of soldiers sent to Roanoke Island returned home little more than a year later due to dwindling supplies, and deteriorating relations with the local Native Americans. The beer wall experience is completely customizable and unlike anything else in the Outer Banks! One rainy spring morning I visit the chief of the Roanoke-Hatteras tribe. -

Indian Peoples, Nations and Violence in the Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake

CERTAINE BOUNDES: INDIAN PEOPLES, NATIONS AND VIOLENCE IN THE SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY CHESAPEAKE By JESSICA TAYLOR A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Jessica Taylor To Mimi, you are worth so much ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my advisor, Juliana Barr, for her thoughtful and sincere support. I am so glad to have her in my life. My committee members Marty Hylton, Jon Sensbach, Elizabeth Dale, and Paul Ortiz each offered different paths to new thoughts and perspectives. My co-workers, students, and friends at the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program helped me gain the confidence to pursue new ideas and goals. I thank all of the wonderful people who have read drafts of chapters and talked ideas through with me including Jeffrey Flanagan, Matt Saionz, Johanna Mellis, Rebecca Lowe, David Shope, Roberta Taylor, Robert Taber, David Brown, Elyssa Hamm. Thank you to Eleanor Deumens for editing my footnotes and offering wonderful suggestions. I thank the Virginia Historical Society, the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, and the Mary and David Harrison Institute for American History, Literature, and Culture for their financial support of my research for this project. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................... -

Red Albion: Genocide and English Colonialism, 1622-1646

RED ALBION: GENOCIDE AND ENGLISH COLONIALISM, 1622-1646 by MATTHEW KRUER A THESIS Presented to the Department ofHistory and the Graduate School ofthe University of Oregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "Red Albion: Genocide and English Colonialism, 1622-1646," a thesis prepared by Matthew Kruer in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master ofArts degree in the Department ofHistory. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Dr. Jiitk M~dd~~, Chai~~i1the Examining Committee Date . Committee in Charge: Dr. Jack Maddex, Chair Dr. Matthew Dennis Dr. Jeffrey Ostler Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Matthew Ryan Kruer IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Matthew Kruer for the degree of Master ofArts in the Department of History to be taken June 2009 Title: RED ALBION: GENOCIDE AND ENGLISH COLONIALISM, 1622-1646 Approved: Dr. Jack Maddex This thesis examines the connection between colonialism and violence during the early years ofEnglish settlement in North America. I argue that colonization was inherently destructive because the English colonists envisioned a comprehensive transformation ofthe American landscape that required the elimination ofNative American societies. Two case studies demonstrate the dynamics ofthis process. During the Anglo-Powhatan Wars in Virginia, latent violence within English ideologies ofimperialism escalated cont1ict to levels ofextreme brutality, but the fracturing ofpower along the frontier limited Virginian war aims to expulsion ofthe Powhatan Indians and the creation ofa segregated society. During the Pequot War in New England, elements ofviolence in the Puritan worldview became exaggerated by the onset ofsocietal crisis during the Antinomian Controversy. -

Roberta Estes

Roberta Estes ect shows significantly less Native American ancestry than would be expected with 96% European or African Within genealogy circles, family stories of Native Y chromosomal DNA. The Melungeons, long held to be American1 heritage exist in many families whose Ameri- mixed European, African and Native show only one can ancestry is rooted in Colonial America and traverses ancestral family with Native DNA.4 Clearly more test- Appalachia. The task of finding these ancestors either ing would be advantageous in all of these projects. genealogically or using genetic genealogy is challenging. This phenomenon is not limited to these groups, and has With the advent of DNA testing, surname and other been reported by other researchers. For example, special interest projects, tools now exist to facilitate the Bolnick (2006) reports finding in 16 Native American tracing of patrilineal and matrilineal lines in present-day populations with northeast or southeast roots that 47% people, back to their origins in either Native Americans, of the families who believe themselves to be full-blooded Europeans, or Africans. This paper references and uses or no less than 75% Native with no paternal European data from several of these public projects, but particular- admixture, find themselves carrying European or ly the Melungeon, Lumbee, Waccamaw, North Carolina African Y chromosomes. Malhi et al. (2008) reported Roots and Lost Colony projects.2 that in 26 Native American populations, non-Native American Y chromosomes occurred at a frequency as The Lumbee have long claimed descent from the Lost high as 88% in the Canadian northeast, southwest of Colony via their oral history.3 The Lumbee DNA Proj- Hudson Bay.