On Frank Stanford's "Battlefield"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CATALOG SEVENTEEN ALEXANDER RARE BOOKS – Literary Firsts & Poetry 234 Camp Street Barre, Vermont 05641 (802) 476-08

CATALOG SEVENTEEN ALEXANDER RARE BOOKS – Literary Firsts & Poetry 234 Camp Street Barre, Vermont 05641 (802) 476-0838 [email protected] AlexanderRareBooks.com All items are American or British hardcover first printings unless otherwise stated. All fully returnable for any reason within 14 days, and offered subject to prior sale. Shipping is free in the US; elsewhere at cost. VT residents please add 6% tax. Mastercard, Visa, PayPal, and checks accepted. Libraries billed according to need. 1) Aldington, Richard. IMAGES OF DESIRE. London: Elkin Mathews, 1919. First edition. 12mo, 38 pp. Red printed wrappers. Several pages not opened. Edges lightly creased, minor paper loss at corners, else about fine. Lovely copy of a fragile book. (6979) $100.00 2) Aldington, Richard. IMAGES - OLD AND NEW. Boston: Four Seas , 1916. First edition. 47 pp. Plain boards in green printed dust jacket. The poet's second book. Spine faded and with lightly chipped head and tail, else about fine. (6978) $75.00 3) Anderson, Maxwell. A STANFORD BOOK OF VERSE 1912-1916. n.p.: The English Club of Stanford University, 1916. First edition. 88 pp. Cloth-backed paper covered boards w/ paper spine label, t.e.g.; in printed dust jacket which repeats the design on the boards. With six poems by Maxwell Anderson among the contributions. An exceptional copy of Anderson's first appearance in book form; he finished his Stanford MA in 1914. End papers offset, else very fine in a faintly tone, chipped along the edges but at least very good and quite scarce dust jacket. (6953) $125.00 4) Ansen, Alan. -

The Light the Dead See by Frank Stanford

The Light The Dead See By Frank Stanford READ ONLINE If you are searching for the ebook by Frank Stanford The Light the Dead See in pdf format, in that case you come on to the loyal website. We presented complete variant of this book in ePub, PDF, DjVu, txt, doc forms. You may read The Light the Dead See online or load. As well, on our site you may reading the guides and other art eBooks online, or downloading their. We will to invite note what our website not store the eBook itself, but we provide ref to the site where you can downloading either reading online. So if have must to downloading by Frank Stanford pdf The Light the Dead See , in that case you come on to right site. We own The Light the Dead See txt, doc, DjVu, PDF, ePub forms. We will be glad if you come back to us more. Soulsavers "the light the dead see" featuring Soulsavers and Dave Gahan discuss their new album "The Light The Dead See," which is now available from Mute Records. [PDF] The Fierce And Beautiful World.pdf Frank stanford | academy of american poets Frank Stanford. 2015. This bed I thought was my past Is really a monk in a garden. He s dressed in white Holding a gourd of water Because I have forgotten Tangle Eye [PDF] The Top 10 Distinctions Between Entrepreneurs And Employees.pdf Frank stanford - wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Leon Stokesbury introduces The Light The Dead See by claiming that Stanford was, The Light The Dead See: Selected Poems of Frank Stanford [PDF] Second Treasury Of Kahlil Gibran.pdf Reviews for the light the dead see by soulsavers - Metacritic Music Reviews, The Light the Dead See by Soulsavers, The British duo worked with Depeche Mode's Dave Gahan on The Light the Dead See. -

Megan Kaminski November 9, 2019

Megan Kaminski November 9, 2019 Department of English 1445 Jayhawk Blvd., Room 3031 Lawrence, KS 66045 [email protected] EDUCATION M.A. Creative Writing, Department of English, University of California, Davis: June 2005. Thesis: Net of Dust *M.F.A. equivalent B.A. English Literature, University of Virginia: May 2001. EMPLOYMENT Associate Professor of Poetry Writing, Department of English, University of Kansas Fall 2018 Assistant Professor of Poetry Writing, Department of English, University of Kansas 2013-present Interim Director of Graduate Creative Writing Program, Department of English, University of Kansas 2014-2015 Creative Writing Lecturer and Academic Program Associate, English Department, University of Kansas 2010-2013 Lecturer, English Department, University of Kansas 2007-2010 Online Instructor, Writing Program, Johns Hopkins University, Center for Talented Youth 2005-2009 Instructor, English Department, Portland Community College 2006-2007 PUBLICATIONS Books, Authored Gentlewomen. Blacksburg, VA: Noemi Press, forthcoming 2020. Deep City. Blacksburg, VA: Noemi Press, 2015. Desiring Map. Atlanta: Coconut Books, 2012. Megan Kaminski, Curriculum Vitae 2 Chapbooks, Authored Withness. Providence: Dusie Press, 2019. Each Acre. Ontario: above/ground press, 2018. Providence. New York: Belladonna*, 2016. Wintering Prairie. Zürich: Dusie Press, 2014. Re-Print: Ontario: above/ground press, 2014. This Place. Zürich: Dusie Press, 2013. Gemology. Houston: Little Red Leaves Textile Series, 2012. Favored Daughter. Chicago: Dancing Girl Press, 2012. Collection. Zürich: Dusie Press, 2011. Carry Catastrophe. Tallahassee: Grey Book Press, 2010. Across Soft Ruins. New York: Scantily Clad Press, 2009. Chapbooks, Coauthored Seven to December (chapbook). w/Bonnie Roy. Grand Rapids: Horse Less Press, 2015. Sigil and Sigh (chapbook). w/Anne Yoder. Chicago: Dusie Press, 2015. -

FIELD, Issue 95, Fall 2016

HH HH FIELD CONTEMPORARY POETRY AND POETICS NUMBER 95 FALL 2016 OBERLIN COLLEGE PRESS EDITORS David Young David Walker ASSOCIATE Pamela Alexander EDITORS Kazim Ali DeSales Harrison Shane McCrae EDITOR-AT- Martha Collins LARGE MANAGING Marco Wilkinson EDITOR EDITORIAL Sarah Goldstone ASSISTANT Juliet Wayne DESIGN Steve Farkas www.oberlin.edu/ocpress Published twice yearly by Oberlin College. Poems should be submitted through the online submissions manager on our website. Subscription orders should be sent to FIELD, Oberlin College Press, 50 N. Professor St., Oberlin, OH 44074. Checks payable to Oberlin College Press: $16.00 a year / $28.00 for two years/ $40.00 for three years. Single issues $8.00 postpaid. Please add $4.00 per year for Canadian addresses and $9.00 for all other countries. Back issues $12.00 each. Contact us about availability. FIELD is also available for download from the Os&ls online bookstore at www.0s-ls.com/field. FIELD is indexed in Humanities International Complete. Copyright © 2016 by Oberlin College. ISSN: 0015-0657 CONTENTS 7 C.D. Wright: A Symposium Jenny Goodman 11 Tough and Tender: The Speaker as Mentor in "Falling Beasts" Laura Kasischke 19 Brighter Is Not Necessarily Better Pamela Alexander 23 Fire and Water Sharon Olds 28 On a First Reading of "Our Dust" Kazim All 32 On "Crescent" Stephen Burt 36 Consolations and Regrets * * * Max Ritvo 43 Uncle Needle 44 December 29 Mimi White 47 The ER James Haug 48 Wood Came Down the River 49 The Turkey Ideal Traci Brimhall 50 Kiinstlerroman Ralph Burns 51 One Afterlife -

The Inventory of the Franz Wright Collection #1709

The Inventory of the Franz Wright Collection #1709 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Wright, Franz #1709 March 3, 2006 Box 1 Folder 1 I. Correspondence. A. Personal. 1. Elizabeth Oehlkers Wright [second wife of FW]. a. Letters (ALS, TLS) to and from FW, 1987-2004; some undated. Folder 2 b. E-mail. Note: many printouts of these and other FW messages contain holograph notations; the messages also include many drafts of poems that FW wrote and sent to others to be read and evaluated. Some of these poems have FW’s holograph corrections. (i) Dec. 18, 1998 - Dec. 20, 2001 Folder 3 (ii) Jan. 4, 2002 - Nov. 23, 2005. Folder 4 2. Liberty Wright Kovacs [mother of FW]. a. Letters (ALS, TLS) from FW. (i) Mar. 1973 - Nov. 1984. Folder 5 (ii) Jan. 1985 - June 2004. Folder 6 b. Letters (ALS, TLS) from Liberty Kovacs to FW, Sep. 1989 - Feb. 2002. 2 Box 1 cont’d. Folder 7 c. E-mail, Oct. 13, 1999 - Nov. 26, 2005. Folder 8 3. Marshall Wright [brother of FW]. a. Letters from Marshall Wright. (i) ALS, n.d. (ii) ALS, n.d., postmarked July 12, 1997. b. Letters from FW. (i) ALS to “Marsh and Andy,” Mar. 4, 1972. (ii) TLS (card) to “Marsh and Andy,” postmarked Oct. 31, 1972. (iii) Holograph message, “from the journals of James Wright,” on 3 x 5” note card, Sep. 7, 1979. 4. Andy Wright [stepbrother of FW]. ALS from FW, Oct. 9, 1985. Folder 9 5. Annie Wright [Edith Ann Runk, stepmother of FW]. a. Letters to FW, 6 ALS and TLS, 1989-2002. -

The Arkansas Poetry Connection

The Arkansas Poetry Connection Lesson Plan by Bonnie Haynie 1998-99 Butler Fellow This lesson plan helps students make a connection between literature, history, geography, and culture through an exploration of the writings of selected Arkansas poets and the events, locations, and people that inspired them. th th Grades: 7 – 12 This plan may be modified for 5th and 6th grade students. Objective: Students will understand the contributions of poetry to Arkansas' culture as well as the impact of Arkansas' characteristics on their poetic voice. Arkansas Curriculum Frameworks: Arkansas History Student Learning Expectations: G.2.5.2 Understand the contributions of people of various racial, ethnic, and religious groups in Arkansas and the United States G.2.6.1 Examine the effects of the contributions of people from selected racial, ethnic, and religious groups to the cultural identify of Arkansas and the United States G.2.6.2 Describe how people from selected racial, ethnic, and religious groups attempt to maintain their cultural heritage while adapting to the culture of Arkansas and the United States TPS.4.AH.7-8.4 Identify the contributions of Arkansas’ territorial officials: * James Miller * Robert Crittenden * Henry Conway * James Conway * Ambrose Sevier * “The Family” W.7. AH.7-8.1 Describe the contributions of Arkansans in the early 1900s WWP.9.AH.7-8.12 Identify significant contributions made by Arkansans in the following fields: * art * business * culture * medicine * science TPS.4.AH.9-12.4 Discuss the historical importance of Arkansas’ territorial officials: * James Miller * Robert Crittenden * Henry Conway * James Conway * Ambrose Sevier * “The Family” W.7. -

Dave Gahan “Angels & Ghosts”: in Italia, Unica

Dave Gahan “Angels & Ghosts”: In Italia, unica data a Milano, il 4 novembre 2015 10/09/2015 Il 23 ottobre 2015 sarà pubblicato “Angels & Ghosts” il nuovo album di Dave Gahan & Soulsavers anticipato dal singolo “All of This and Nothing”, in uscita oggi, ed in radio da domani 11 settembre 2015 La band terrà sei concerti intimi ed esclusivi negli USA e in Europa. In Italia, unica data a Milano, il 4 novembre 2015 Il 23 ottobre Dave Gahan, inimitabile voce dei Depeche Mode nonché artista che ha raggiunto il traguardo del multiplatino, pubblicherà un nuovo album insieme ai Soulsavers. Questo secondo disco, nato dal loro sodalizio, si intitola “Angels & Ghosts” ed è il seguito dell’acclamato The Light the Dead See del 2012, pubblicato da Columbia Records che uscirà in contemporanea mondiale in CD, vinile ed in digitale il 23 ottobre 2015. Questo lavoro discografico assolutamente irresistibile conterrà nove brani inediti, tutti scritti da Dave Gahan & Soulsavers. Con il suo piglio deciso, “Angels & Ghosts” rappresenta un’evoluzione rispetto al loro primo album. Si preannuncia un mix di sonorità scure, elementi di matrice gospel e blues e quella nuda bellezza che è diventata il marchio di fabbrica delle canzoni di Dave e dei Soulsavers. Potente ed emozionante come mai prima d’ora, la voce di Gahan traina l’album verso un paesaggio sonoro dall’orchestrazione estremamente raffinata. Quella che ha portato alla realizzazione del disco è stata una vera e propria collaborazione transoceanica. Dave Gahan e Rich Machin si sono scambiati demo e idee dai propri studi, rispettivamente a Manhattan e nella campagna inglese, per poi incidere l’album con musicisti aggiuntivi in leggendarie sale di incisione di tutto il mondo, tra cui il Sunset Sound a Los Angeles ed Electric Lady a New York. -

LE MYTHE Patti Smith

MUSIQUE CROCODILES 07 THE DODOZ 14 LIZA MANILI 14 SINGTANK 15 THE BEACH BOYS 17 UP MELODY GARDOT 17 SAINT ETIENNE 18 DVD LA TAUPE 20 CHEVAL DE GUERRE 21 NUMÉRO 173 START JUIN 2012 UNE VIE MEILLEURE 22 THE DESCENDANTS 22 L’ACTUALITÉ MUSIQUE ET VIDÉO DE VOTRE SPÉCIALISTE CULTURE ILLEGAL TRAFFIC 24 JASON PRIESTLEY 30 PLeA mTyTthI e SMITH + HOT CHIP GARBAGE UNE PUBLICATION SLASH SOMMAIRE UP START SOCIÉTÉ ÉDITRICE : GROUPE EXPRESS-ROULARTA SA DE 47 150 040 EUROS SIÈGE SOCIAL : 29, RUE DE CHÂTEAUDUN, 75009 PARIS TEL. : 01.75.55.10.00 RCS 552 018 681 PARIS CONSEIL D’ADMINISTRATION : RIK DE NOLF (PRÉSIDENT), FRANCIS BALLE (VICE-PRÉSIDENT), PHILIPPE BIDALON, JEAN-ANTOINE BOUCHEZ, XAVIER BOUCKAERT, JAN STAELENS, MAXIME DE JENLIS, BARON HUGO VANDAMME, BRIGITTE GAUTHIER-DARCET, 10 MONIQUE CANTO-SPERBER PRÉSIDENT-DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL RIK DE NOLF DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAUX DÉLÉGUÉS : CORINNE PITAVY, CHRISTOPHE BARBIER DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION : CHRISTOPHE BARBIER RÉDACTION RÉDACTRICE EN CHEF FLORENCE RAJON frajon @lexpress.fr RÉDACTEURS 07 DAVID BOUSEUL, LAURENT DENNER, HERVÉ CRESPI, MAXIME GOGUET, HÉLÉNA MCDOUGLAS, MARC RIBEROLLES 12 CONCEPTION GRAPHIQUE DIDIER FITAN MANAGEMENT ÉDITEUR DÉLÉGUÉ TRISTAN THOMAS DIRECTRICE RÉGIE VALÉRIE SALOMON 13 20 PUBLICITÉ 30 TRISTAN THOMAS [email protected] FABRICATION MUSIQUE DVD PASCAL DELEPINE AVEC LAURENCE BIDEAU PRÉPRESSE 07 Hot Chip 20 La Taupe GROUPE EXPRESS-ROULARTA 07 Crocodiles 21 Cheval de guerre IMPRIMÉ EN BELGIQUE ROULARTA PRINTING 08 Patti Smith 22 Une vie meilleure COUVERTURE © TOUS DROITS RÉSERVÉS. 10 -

Nick Waterhouse

Het blad van/voor muziekliefhebbers 8 juni 2012 nr. 288 No Risk Disc: NICK WATERHOUSE www.platomania.nl • www.sounds-venlo.nl • www.kroese-online.nl • www.velvetmusic.nl • www.waterput.nl • www.de-drvkkery.nl adv_umg_plato mania_3fm_fc_©OCHEDA 16-05-12 14:03 Pagina 1 mANIA 288 VOOR DE ECHTE N RISK MUZIEKLIEFHEBBER! DISCNIET GOED GELD TERUG NICK WATERHOUSE Time’s All Gone (V2) Time’s All Gone is het sprankelende en soulvolle debuutalbum van Nick Waterhouse. Hij maakt r&b in de beste jaren vijftig traditie met hedendaagse WILL AND THE PEOPLE LION IN THE MORNING SUN 01 GOTYE SOMEBODY THAT I USED TO KNOW (FEATURING KIMBRA) OF MONSTERS AND MEN LITTLE TALKS 02 BEN HOWARD KEEP YOUR HEAD UP invloeden. Vette blazers (oudgediende Ira Raibon op YOUNG THE GIANT MY BODY 03 TRIGGERFINGER I FOLLOW RIVERS (LIVE@GIEL) baritonsax), koortjes (The Naturelles), analoge sound. THE ROOTS & CODY CHESTNUTT THE SEED (2.0) 04 EMELI SANDE NEXT TO ME (ACOUSTIC VERSION) GO BACK TO THE ZOO SMOKING ON THE BALCONY 05 JAMIE WOON NIGHT AIR De 25-jarige, uit Californië afkomstige zanger is het best TWO DOOR CINEMA CLUB UNDERCOVER MARTYN 06 LANA DEL REY VIDEO GAMES te scharen in het rijtje Sharon Jones, Mark Ronson, Amy SIA CLAP YOUR HANDS 07 EMMA LOUISE JUNGLE HUNGRY KIDS OF HUNGARY SCATTERED DIAMONDS 08 KEANE SILENCED BY THE NIGHT Winehouse en Stones Throw-labelgenoot Aloe Blacc. ALEX CLARE TOO CLOSE 09 AGNES OBEL JUST SO De sound ligt soms heerlijk dichtbij de iets rauwere CRYSTAL FIGHTERS PLAGE 10 FINK YESTERDAY WAS HARD ON ALL OF US WILLY MOON I WANNA BE YOUR MAN 11 THE KOOKS IS IT ME rockabilly, zowel door zijn stem als door de van tijd THE ASTEROIDS GALAXY TOUR HEART ATTACK 12 FLORENCE + THE MACHINE SHAKE IT OUT tot tijd scheurende gitaar van Waterhouse. -

Bronwen R. Tate

BRONWEN R. TATE #410–6038 Birney Ave. (503) 758-6264 (cell) Vancouver, BC [email protected] V6s 0L4 Canada www.bronwentate.com EDUCATION 2014 Ph.D., Stanford University, Comparative Literature 2006 M.F.A., Brown University Literary Arts: Poetry 2003 A.B. with Honors, Brown University, Comparative Literature: Literary Translation CURRENT POSITION Assistant Professor of Teaching, University of British Columbia, Creative Writing Program, July 2020– ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT Director of Writing, Marlboro College, 2019–2020 Assistant Professor of Creative Writing and Literature, Marlboro College, 2017–2020 Thinking Matters Fellow, Stanford Introductory Studies, Stanford University, 2014–2017 RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTERESTS Creative Writing, 20th Century North American Literature, Poetry and Poetics, The Ethics of Reading, Transnational Literary Studies, Literature and the Environment, Gender Studies PUBLICATIONS Poetry Book 2021 The Silk the Moths Ignore, 2019 Hillary Gravendyk Prize National Winner, I Inlandia Institute, forthcoming Spring 2021. * Finalist or semi-finalist for 8 previous awards, including University of Akron Poetry Prize 2019 Finalist, Cleveland State University Poetry Center’s First Book Poetry Competition 2019 Honorable Mention (Selected by Judge Brenda Hillman) Poetry Chapbooks 2019 Mitten: Scraps & Patterns (Dusie Press) 2016 Vesper Vigil (above/ground press) 2011 If a Thermometer (dancing girl press) 2010 The Loss Letters (Dusie Press) Tate 2 2009 Scaffolding: My Proust Vocabulary (Dusie Press) 2008 Like the Native Tongue -

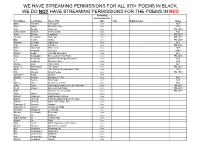

We Have Streaming Permissions for All 970+ Poems in Black. We Do Not Have Streaming Permissions for the Poems in Red

WE HAVE STREAMING PERMISSIONS FOR ALL 970+ POEMS IN BLACK. WE DO NOT HAVE STREAMING PERMISSIONS FOR THE POEMS IN RED. Streaming Permissions for First Name Last Name Poem Title 2021 Text Rightsholder Notes Mary Avidano City Lights yes ALP Ellen Bass Dead Butterfly yes ALP Amy Beeder Cabezon yes PM 2004 Cathy Smith Bowers Peace Lilies yes ALP John Brehm Layabout yes PM 2001 Joseph Campana First Job yes PM 2002 Billy Collins Today yes PM 2000 Barbara Crooker Sparklers yes ALP Carl Dennis Candles yes PM 2002 Karin Gottshall More Lies yes ALP Tami Haaland Little Girl yes ALP? Robert Hedin The Old Liberators yes ALP Tony Hoagland Requests for Toy Piano yes PM 2006 X.J. Kennedy Old Men Pitching Horseshoes yes ALP J.T. Ledbetter Elegy for Blue yes ALP Denise Low Two Gates yes ALP Joanie V. Mackowski The Larger yes PM 2003 Matt Mason The Story of Ferdinand the Bull yes ALP WS Merwin Good People yes PM 1999 Josephine Miles Desert yes Marilyn Nelson Daughters 1900 yes ALP D. Nurkse First Night yes ALP Alberto Rios We Are of a Tribe yes ALP Gary Soto Self-Inquiry Before the Job Interview yes PM 2001 Dean Young Elegy on Toy Piano yes PM 2003 Kabir Brother, I've seen some yes PM 2011 Chris Abani War Widow yes Robert Adamson Australasian Darters yes Zubair Ahmed I Eat Breakfast to Begin the Day yes Dilruba Ahmed Snake Oil, Snake Bite yes Francisco X Alarcon Jaguar yes Francisco X Alarcon Words are Birds yes Richard Aldington Le Maudit yes Meena Alexander Revenant yes Kazim Ali Explorer yes Agha Shahid Ali Prayer Rug yes Kazim Ali Rain yes Dick Allen -

University of Arizona Poetry Center L.R. Benes Rare Book Room Holdings Last Updated 01/13/2017

UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA POETRY CENTER L.R. BENES RARE BOOK ROOM HOLDINGS LAST UPDATED 01/13/2017 This computer-generated list is accurate to the best of our knowledge, but may contain some formatting issues and/or inaccuracies. Thank you for your understanding. AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER Seeds yet ever secret : poems and Abbey, Rita Deanin. images / Rita Deanin Abbey. Las Vegas, Nev. : Gan Or, 2013. Always hook a a gift horsey dead in the kisser : [an invocation] / text by Emily Abendroth illustrations by Houston, Texas : little red leaves, Abendroth, Emily, author. Jenna Peters-Golden. 2015. When I grow up I want to be a mighty tall order / by Emily Brooklyn, N.Y. : Belladonna* Abendroth, Emily, author. Abendroth. Collaborative, 2013. Exclosures : 1 - 8 / Emily Philadelphia, PA : Albion Books, Abendroth, Emily. Abendroth. 2012. Notwithstanding shoring, flummox [Houston, Tex] : little red leaves, Abendroth, Emily. / Emily Abendroth. c2012. Philosophies of the dusk : poems / by W. M. Aberg and Michael Tucson, Ariz. : Pima College Aberg, W. M. Knoll. 1984. Philosophies of the dusk : poems / by W. M. Aberg and Michael Tucson, Ariz. : Pima College Aberg, W. M. Knoll. 1984. A house on a hill (part 3) / by Tuscaloosa : Slash Pine Press, Abramowitz, Harold. Harold Abramowitz. 2010. Tenants of the House Poems 1951- Abse, Dannie. 56. London, Eng. Hutchinson 1957. New York : Center for the Homage to LeRoi Jones and other Humanities, the Graduate Center, early works / Kathy Acker; The City University of New Acker, Kathy, 1948-1997, author. Gabrielle Kappes, editor. York, 2015. Other ends pine / Patrick AD, David Feil, Rebecca Novak, Dawn [Houston, Tex.] : little red leaves, AD, Patrick.