Race and Essentialism in Gloria Steinem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critically Evaluate the Understanding of Gender As Discourse

Vol. 1, No. 2 International Education Studies Critically Evaluate the Understanding of Gender as Discourse Changxue Xue College of Foreign languages, Yanshan University Qinhuangdao 066004, China Tel: 86-335-805-8710 Email: [email protected] Abstract In this paper, the author explores the different views on gender and the nature of gender as discourse. Furthermore, the author argues that discursive psychology’s views on gender are convincing and explain more than other perspectives of gender. Keywords: Gender, Essentialism, Constructionism Since the 1950s, an increasing use of the term gender has been seen in the academic literature and the public discourse for distinguishing gender identity from biological sex. Money and Hampson (1955) defined the term gender as what a person says or does to reveal that he or she has the status of being boy or girl, man or woman (masculinity or femininity of a person). Gender is a complex issue, constituents of which encompass styles of dressing, patterns of moving as well as ways of talking rather than just being limited to biological sex. Over the years, the perception of the issue ‘gender’ has been changing and developing from essentialism to social constructionism. Essentialism suggests that gender is a biological sex, by contrast, social constructionism suggests that gender is constructed within a social and cultural discourse. Due to its complex nature, gender intrigues numerous debates over the extent to which gender is a biological construct or a social construct. Social constructionists employ discourse analysis as a method for research on gender identity. Discursive psychology is one of most important approaches within discourse analysis in the field of social psychology. -

Dalit Feminism: a Voice for the Voiceless in Aruna Gogulamanda's

SHANLAX s han lax International Journal of English # S I N C E 1 9 9 0 Dalit Feminism: A Voice for the Voiceless in Aruna Gogulamanda’s “A OPEN ACCESS Dalit Woman in the Land of Goddesses” P. Gopika Unni Manuscript ID: Post Graduation Department of English ENG-2020-08032269 Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, Kalady, Eranakulam, Kerala, India https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7604-2480 Volume: 8 Abstract Issue: 3 Dalit Feminism is feminism, which has great significance in the contemporary casteist society. It aims at equality, right, and justice for the lowest strata of the society, that is, Dalit Women. Aruna Month: June Gogulamanda’s “A Dalit Woman in the land of Goddesses” focuses on the double-edged sword of marginalization, which a Dalit woman has to suffer in the patriarchal casteist era, both as a Year: 2020 woman and also as a Dalit. She is a poet who articulates her voice for the voiceless section of the society, that is, the Dalit women, who are suppressed in the hands of male chauvinism. P-ISSN: 2320-2645 Keywords: Dalit, Dalit feminism, Double-edged sword, Marginalization, Patriarchal and Male chauvinism. E-ISSN: 2582-3531 Introduction Received: 17.02.2020 Aruna Gogulamanda is a Telugu- English Dalit Poet. She comes from Accepted: 19.05.2020 a middle – class agricultural family. She was a research scholar at the University of Hyderabad. She worked on “Dalit and Non-Dalit Women’s Published: 02.06.2020 Autobiographies.” She is one of the emerging Intellectual Dalit Feminist and Dalit womanist poets from Telangana. -

The Feminist Movement By: Emera Cooper What Is Feminism? and What Do Feminists Do?

The Feminist Movement By: Emera Cooper What is Feminism? And what do feminists do? Feminism is the advocacy of women's rights on the basis of the equality of the sexes. ★ Work to level the playing field between genders ★ Ensure that women and girls have the same opportunities in life available to boys and men ★ Gain overall respect for women’s experiences, identities, knowledge and strengths ★ Challenge the systemic inequalities women face on a daily basis History behind the Feminist Movement First wave feminism (property and voting rights): In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott hosted the Seneca Falls Convention where they proclaimed their Declaration of Sentiments. From that we have the famous quote, “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal”. They also demanded the right to vote. The women's suffrage movement had begun. With the exceptional work done by women during WWI, the 19th Amendment was passed granting women the right to vote. Women began to enter the workplace following The Great Depression. Women had active roles in the military during WWII. Following the Civil Rights movement, the Equal Pay Act was passed in 1963 to begin to address the unequal pay women in the workplace faced. Second wave feminism (equality and discrimination): In 1971, feminist Gloria Steinem joined Betty Friedan and Bella Abzug in founding the National Women’s Political Caucus. During this time many people had started referring to feminism as “women’s liberation.” In 1972 the Equal Rights Amendment was passed and women gained legal equality and discrimination of sex was banned. -

Celebrating Women's History Month

March 2021 - Celebrating Women’s History Month It all started with a single day in 1908 in New York City when thousands of women marched for better labor laws, conditions, and the right to vote. A year later on February 28, in a gathering organized by members of the Socialist Party, suffragists and socialists gathered again in Manhattan for what they called the first International Woman’s Day. The idea quickly spread worldwide from Germany to Russia. In 1911, 17 European countries formally honored the day as International Women’s day. By 1917 with strong influences and the beginnings of the Russian Revolution communist leader Vladimir Lenin made Women’s Day a soviet holiday. But due to its connections to socialism and the Soviet Union, the holiday wasn’t largely celebrated in the United States until 1975. That’s when the United Nations officially began sponsoring International Woman’s day. In 1978 Woman’s Day grew from a day to a week as the National Women’s History Alliance became frustrated with the lack of information about women’s history available to public school curriculums. Branching off of the initial celebration, they initiated the creation of Women’s History week. And by 1980 President Jimmy Carter declared in a presidential proclamation that March 8 was officially National Women’s History Week. As a result of its country wide recognition and continued growth in state schools, government, and organizations by 1986, 14 states had gone ahead and dubbed March Women’s History Month. A year later, this sparked congress to declare the holiday in perpetuity. -

Gender/Sex Diversity Beliefs: Heterogeneity, Links to Prejudice, and Diversity-Affirming Interventions by Zachary C

Gender/Sex Diversity Beliefs: Heterogeneity, Links to Prejudice, and Diversity-Affirming Interventions by Zachary C. Schudson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Psychology and Women’s Studies) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Sari van Anders, Co-Chair Professor Susan Gelman, Co-Chair Professor Anna Kirkland Associate Professor Sara McClelland Zach C. Schudson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-1300-5674 © Zach C. Schudson ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the many people who made this dissertation possible. First and foremost, thank you to Dr. Sari van Anders, my dissertation advisor and co-chair and my mentor. I have never met someone more committed to social justice through psychological research or to their students. Your expansive, nuanced thinking about gender and sexuality, your incredible, detailed feedback on everything I wrote, your lightning-quick, thoughtful responses whenever I needed anything, and your persistence in improving communication even when it was difficult all make me feel astoundingly lucky. Despite the many time and energy-intensive challenges you have faced over the last several years, you have done everything you can to facilitate my success as a scholar, all the while showing deep care for my well-being as a person. Thank you also to Dr. Susan Gelman, my dissertation co-chair, for your incredible support these last feW years. Your intellectual generosity is truly a gift; I feel smarter and more capable every time we speak. Thank you to Drs. Sara McClelland and Anna Kirkland, members of my dissertation committee and my teaching mentors. -

Play Guide for Gloria

Play Guide September 28-October 20, 2019 by Emily Mann directed by Risa Brainin 2019 and the recent past. This new work by Tony Award-winning playwright Emily Mann celebrates the life of one of the most important figures of America's feminist movement! Nearly half a century later, Ms. Steinem's fight for gender equality is still a battle yet to besimplifying won. IT 30 East Tenth Street Saint Paul, MN 55101 651-292-4323 Box Office 651-292-4320 Group Sales historytheatre.com Page 2 Emily Mann—Playwright Pages 3-4 Gloria Steinem Timeline Page 5-7 Equal Rights Amendment Page 8-11 Second Wave Feminism Page 12 National Women’s Conference Page 13 Phyllis Schlafly Pages 14-15 Milestones in U.S. Women’s History Page 16 Discussion Questions/Activities Page 17 Books by Gloria Steinem able of Content T Play Guide published by History Theatre c2019 Emily Mann (Playwright, Artistic Director/Resident Playwright) is in her 30th and final season as Artistic Director and Resident Playwright at the McCarter Theatre Center in Princeton, New Jersey. Her nearly 50 McCarter directing credits include acclaimed produc- tions by Shakespeare, Chekhov, Ibsen, and Williams and the world premieres of Christopher Durang’s Turning Off the Morning News and Miss Witherspoon; Ken Ludwig’s Murder on the Orient Express; Rachel Bonds’ Five Mile Lake; Danai Guri- ra’s The Convert; Sarah Treem’s The How and the Why; and Edward Albee’s Me, Myself & I. Broadway: A Streetcar Named Desire, Anna in the Tropics, Execution of Justice, Having Our Say. -

Feminism & Philosophy Vol.5 No.1

APA Newsletters Volume 05, Number 1 Fall 2005 NEWSLETTER ON FEMINISM AND PHILOSOPHY FROM THE EDITOR, SALLY J. SCHOLZ NEWS FROM THE COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN, ROSEMARIE TONG ARTICLES MARILYN FISCHER “Feminism and the Art of Interpretation: Or, Reading the First Wave to Think about the Second and Third Waves” JENNIFER PURVIS “A ‘Time’ for Change: Negotiating the Space of a Third Wave Political Moment” LAURIE CALHOUN “Feminism is a Humanism” LOUISE ANTONY “When is Philosophy Feminist?” ANN FERGUSON “Is Feminist Philosophy Still Philosophy?” OFELIA SCHUTTE “Feminist Ethics and Transnational Injustice: Two Methodological Suggestions” JEFFREY A. GAUTHIER “Feminism and Philosophy: Getting It and Getting It Right” SARA BEARDSWORTH “A French Feminism” © 2005 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN: 1067-9464 BOOK REVIEWS Robin Fiore and Hilde Lindemann Nelson: Recognition, Responsibility, and Rights: Feminist Ethics and Social Theory REVIEWED BY CHRISTINE M. KOGGEL Diana Tietjens Meyers: Being Yourself: Essays on Identity, Action, and Social Life REVIEWED BY CHERYL L. HUGHES Beth Kiyoko Jamieson: Real Choices: Feminism, Freedom, and the Limits of the Law REVIEWED BY ZAHRA MEGHANI Alan Soble: The Philosophy of Sex: Contemporary Readings REVIEWED BY KATHRYN J. NORLOCK Penny Florence: Sexed Universals in Contemporary Art REVIEWED BY TANYA M. LOUGHEAD CONTRIBUTORS ANNOUNCEMENTS APA NEWSLETTER ON Feminism and Philosophy Sally J. Scholz, Editor Fall 2005 Volume 05, Number 1 objective claims, Beardsworth demonstrates Kristeva’s ROM THE DITOR “maternal feminine” as “an experience that binds experience F E to experience” and refuses to be “turned into an abstraction.” Both reconfigure the ground of moral theory by highlighting the cultural bias or particularity encompassed in claims of Feminism, like philosophy, can be done in a variety of different objectivity or universality. -

Ma-Womens-Studies 79.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF MADRAS M.A .DEGREE COURSE IN WOMEN'S STUDIES CHOICE-BASED CREDIT SYSTEM DEPARTMENT OF WOMEN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF MADRAS REGULATIONS (With effect from the academic year 2016–17) 1. CONDITIONS FOR ADMISSION Any Bachelor (Under-graduate) Degree holder of the University of Madras or any other University or a qualification accepted by the Syndicate of this University as equivalent thereto. 2. DURATION OF THE COURSE The course of the Degree of Master of Arts in Women's Studies shall consist of four semesters over two academic years. Each semester will have a minimum of 90 working days and each day will have five working hours. Teaching is organized into a modular pattern of credit courses. Credit is normally related to the number of instructional hours a teacher teaches a particular subject. It is also related to the number of hours a student spends learning a subject or carrying out an activity. 3. EXAMINATION AND EVALUATION 3.1.Continuous Internal Assessment (CIA) • Sessional Test I will be conducted during the sixth week of each semester for the syllabus covered till then. • Sessional Test II will be conducted during the eleventh week of each semester for the syllabus covered between the seventh and eleventh week of that semester. • Sessional tests (of one to two hours duration) may employ one or more assessment tools such as assignments and seminars suitable to the subject. Students will be informed in advance about the nature of the assessment and shall have to compulsorily attend the two sessional tests, failing which they will not be allowed to appear for the End-semester examination. -

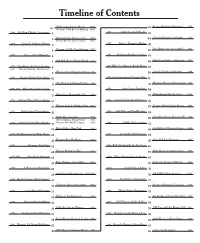

Timeline of Contents

Timeline of Contents Roots of Feminist Movement 1970 p.1 1866 Convention in Albany 1866 42 Women’s 1868 Boston Meeting 1868 1970 Artist Georgia O’Keeffe 1869 1869 Equal Rights Association 2 43 Gain for Women’s Job Rights 1971 3 Elizabeth Cady Stanton at 80 1895 44 Harriet Beecher Stowe, Author 1896 1972 Signs of Change in Media 1906 Susan B. Anthony Tribute 4 45 Equal Rights Amendment OK’d 1972 5 Women at Odds Over Suffrage 1907 46 1972 Shift From People to Politics 1908 Hopes of the Suffragette 6 47 High Court Rules on Abortion 1973 7 400,000 Cheer Suffrage March 1912 48 1973 Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs 1912 Clara Barton, Red Cross Founder 8 49 1913 Harriet Tubman, Abolitionist Schools’ Sex Bias Outlawed 1974 9 Women at the Suffrage Convention 1913 50 1975 First International Women’s Day 1914 Women Making Their Mark 10 51 Margaret Mead, Anthropologist 1978 11 The Woman Sufferage Parade 1915 52 1979 Artist Louise Nevelson 1916-1917 Margaret Sanger on Trial 12 54 Philanthropist Brooke Astor 1980 13 Obstacles to Nationwide Vote 1918 55 1981 Justice Sandra Day O’Connor 1919 Suffrage Wins in House, Senate 14 56 Cosmo’s Helen Gurley Brown 1982 15 Women Gain the Right to Vote 1920 57 1984 Sally Ride and Final Frontier 1921 Birth Control Clinic Opens 16 58 Geraldine Ferraro Runs for VP 1984 17 Nellie Bly, Journalist 1922 60 Annie Oakley, Sharpshooter 1926 NOW: 20 Years Later 1928 Amelia Earhart Over Atlantic 18 Victoria Woodhull’s Legacy 1927 1986 61 Helen Keller’s New York 1932 62 Job Rights in Pregnancy Case 1987 19 1987 Facing the Subtler -

In Memoriam Newspaper Clipping, Florida Times Union

~-----===~~--~~~--~==~--------~------- EDNA L. SAFFY 1935-2010 Human rights activist founded NOW chapters She was a long-time, changed to read, "All people are a member of the Duval County Edna Saffy created equal ..." . Democratic Executive Com was a rights very active supporter of Dr. Saffy, human rights ac mittee for 35 years. In 1991, activist, women's liberation. tivist, retired college professor during the campaign for the professor and founder of NOW chapters 1992 Democratic presidential and NOW By JESSIE-LYNNE KERR in Jacksonville and Gainesville, primary, she hosted Bill Clinton The Times-Union died at her Jacksonville home at her Southside home. Active chapter Sunday 1110rning after a year in Mideast peace groups and a founder. Edna L. Saffy was such a long battle with brain cancer. member of the American Arab She died leader in the women's rights Shewas75. Institute, she later made at least Sunday. movement that she told a re Funeral arrangements are five trips to the Clinton White porter in 19~5 that she wanted pending. House, including being invited BRUCE to see the wording of the In addition to her work for LIPSKY/The Declaration of Independence women's rights, Dr. Saffy was SAFFY continues on A-7 Times-Union .. withdrawn earlier, she had Saffy only failing grades on her Continued from A·l record and no one would let her enroll. She finally found a sympathetic professor who by the president to witness the gave her a second chance. She signing of the Mid-East Peace proved him right by earning Accord in 1993. -

Delayed Critique: on Being Feminist, Time and Time Again

Delayed Critique: On Being Feminist, Time and Time Again In “On Being in Time with Feminism,” Robyn Emma McKenna is a Ph.D. candidate in English and Wiegman (2004) supports my contention that history, Cultural Studies at McMaster University. She is the au- theory, and pedagogy are central to thinking through thor of “‘Freedom to Choose”: Neoliberalism, Femi- the problems internal to feminism when she asks: “… nism, and Childcare in Canada.” what learning will ever be final?” (165) Positioning fem- inism as neither “an antidote to [n]or an ethical stance Abstract toward otherness,” Wiegman argues that “feminism it- In this article, I argue for a systematic critique of trans- self is our most challenging other” (164). I want to take phobia in feminism, advocating for a reconciling of seriously this claim in order to consider how feminism trans and feminist politics in community, pedagogy, is a kind of political intimacy that binds a subject to the and criticism. I claim that this critique is both delayed desire for an “Other-wise” (Thobani 2007). The content and productive. Using the Michigan Womyn’s Music of this “otherwise” is as varied as the projects that femi- Festival as a cultural archive of gender essentialism, I nism is called on to justify. In this paper, I consider the consider how rereading and revising politics might be marginalization of trans-feminism across mainstream, what is “essential” to feminism. lesbian feminist, and academic feminisms. Part of my interest in this analysis is the influence of the temporal Résumé on the way in which certain kinds of feminism are given Dans cet article, je défends l’idée d’une critique systéma- primacy in the representation of feminism. -

Assistant Professor, Department of English, Periyar University, Salem-636011, Tamilnadu, India

Name : Dr.B.J.Geetha Designation : Assistant Professor Official Address : Assistant Professor, Department of English, Periyar University, Salem-636011, Tamilnadu, India. Mobile : 9791201942 Email : [email protected] Qualification : MA, MPhil, MSc, PhD. Total Teaching Experience : 14 years 6 months No of Books Published : Two 1. Enrich your English 2. Literary Quiz Training Programmes Attended : 1. Orientation Course at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi from 27/9/2010 to25/10/2010. 2. ni-msme- National Institute for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises- Faculty Development Programme in Entrepreneurship- Sponsored by the Department of Science & Technology, Govt of India at PRIMS Periyar University, Salem from 9/3/2011 to 20/3/2011. 3. UGC Sponsored National Workshop on Applications of Projective Assessment organised by the Dept of Psychology, Periyar University, Salem on 13 &14/10/2011. 4. Refresher Course in English at University of Madras, Chennai from 29/08/2013 to 18/09/2013. No of Publication : 28 No of International Journal Publication-10 1. Rescue Triangle in Tughlaq, Caligula and Macbeth- Rock Pebbles, A Peer - Reviewed International Literary Journal. Jan-June 2009 Vol–XIII NO.1 Page.97- 102. Author: B.J.Geetha. 2. Compassion and Advocacy for Non-Human Animals With Reference to Moby Dick – Voices - International Peer - Reviewed Journal Tone 6, 2010, Vol- VI.Page.98-106. Author: B.J.Geetha. 3. Lesbian and Post Modern Perspectives in the Select Novels of Jeanette Winterson-Labyrinth International Journal. Vol.2/No.2-April 2011.Page.114-120. Author: B.J.Geetha. 4. The Making of Modern World and its Anguish Reflected in Mahapatra’s Poetry- Rock Pebbles A Peer - Reviewed International Literary Journal Jan-June Vol.