My Life on the Road / Gloria Steinem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Feminist Movement By: Emera Cooper What Is Feminism? and What Do Feminists Do?

The Feminist Movement By: Emera Cooper What is Feminism? And what do feminists do? Feminism is the advocacy of women's rights on the basis of the equality of the sexes. ★ Work to level the playing field between genders ★ Ensure that women and girls have the same opportunities in life available to boys and men ★ Gain overall respect for women’s experiences, identities, knowledge and strengths ★ Challenge the systemic inequalities women face on a daily basis History behind the Feminist Movement First wave feminism (property and voting rights): In 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott hosted the Seneca Falls Convention where they proclaimed their Declaration of Sentiments. From that we have the famous quote, “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal”. They also demanded the right to vote. The women's suffrage movement had begun. With the exceptional work done by women during WWI, the 19th Amendment was passed granting women the right to vote. Women began to enter the workplace following The Great Depression. Women had active roles in the military during WWII. Following the Civil Rights movement, the Equal Pay Act was passed in 1963 to begin to address the unequal pay women in the workplace faced. Second wave feminism (equality and discrimination): In 1971, feminist Gloria Steinem joined Betty Friedan and Bella Abzug in founding the National Women’s Political Caucus. During this time many people had started referring to feminism as “women’s liberation.” In 1972 the Equal Rights Amendment was passed and women gained legal equality and discrimination of sex was banned. -

Celebrating Women's History Month

March 2021 - Celebrating Women’s History Month It all started with a single day in 1908 in New York City when thousands of women marched for better labor laws, conditions, and the right to vote. A year later on February 28, in a gathering organized by members of the Socialist Party, suffragists and socialists gathered again in Manhattan for what they called the first International Woman’s Day. The idea quickly spread worldwide from Germany to Russia. In 1911, 17 European countries formally honored the day as International Women’s day. By 1917 with strong influences and the beginnings of the Russian Revolution communist leader Vladimir Lenin made Women’s Day a soviet holiday. But due to its connections to socialism and the Soviet Union, the holiday wasn’t largely celebrated in the United States until 1975. That’s when the United Nations officially began sponsoring International Woman’s day. In 1978 Woman’s Day grew from a day to a week as the National Women’s History Alliance became frustrated with the lack of information about women’s history available to public school curriculums. Branching off of the initial celebration, they initiated the creation of Women’s History week. And by 1980 President Jimmy Carter declared in a presidential proclamation that March 8 was officially National Women’s History Week. As a result of its country wide recognition and continued growth in state schools, government, and organizations by 1986, 14 states had gone ahead and dubbed March Women’s History Month. A year later, this sparked congress to declare the holiday in perpetuity. -

Play Guide for Gloria

Play Guide September 28-October 20, 2019 by Emily Mann directed by Risa Brainin 2019 and the recent past. This new work by Tony Award-winning playwright Emily Mann celebrates the life of one of the most important figures of America's feminist movement! Nearly half a century later, Ms. Steinem's fight for gender equality is still a battle yet to besimplifying won. IT 30 East Tenth Street Saint Paul, MN 55101 651-292-4323 Box Office 651-292-4320 Group Sales historytheatre.com Page 2 Emily Mann—Playwright Pages 3-4 Gloria Steinem Timeline Page 5-7 Equal Rights Amendment Page 8-11 Second Wave Feminism Page 12 National Women’s Conference Page 13 Phyllis Schlafly Pages 14-15 Milestones in U.S. Women’s History Page 16 Discussion Questions/Activities Page 17 Books by Gloria Steinem able of Content T Play Guide published by History Theatre c2019 Emily Mann (Playwright, Artistic Director/Resident Playwright) is in her 30th and final season as Artistic Director and Resident Playwright at the McCarter Theatre Center in Princeton, New Jersey. Her nearly 50 McCarter directing credits include acclaimed produc- tions by Shakespeare, Chekhov, Ibsen, and Williams and the world premieres of Christopher Durang’s Turning Off the Morning News and Miss Witherspoon; Ken Ludwig’s Murder on the Orient Express; Rachel Bonds’ Five Mile Lake; Danai Guri- ra’s The Convert; Sarah Treem’s The How and the Why; and Edward Albee’s Me, Myself & I. Broadway: A Streetcar Named Desire, Anna in the Tropics, Execution of Justice, Having Our Say. -

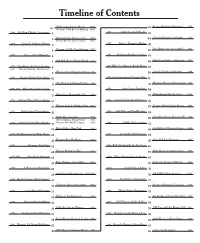

Timeline of Contents

Timeline of Contents Roots of Feminist Movement 1970 p.1 1866 Convention in Albany 1866 42 Women’s 1868 Boston Meeting 1868 1970 Artist Georgia O’Keeffe 1869 1869 Equal Rights Association 2 43 Gain for Women’s Job Rights 1971 3 Elizabeth Cady Stanton at 80 1895 44 Harriet Beecher Stowe, Author 1896 1972 Signs of Change in Media 1906 Susan B. Anthony Tribute 4 45 Equal Rights Amendment OK’d 1972 5 Women at Odds Over Suffrage 1907 46 1972 Shift From People to Politics 1908 Hopes of the Suffragette 6 47 High Court Rules on Abortion 1973 7 400,000 Cheer Suffrage March 1912 48 1973 Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs 1912 Clara Barton, Red Cross Founder 8 49 1913 Harriet Tubman, Abolitionist Schools’ Sex Bias Outlawed 1974 9 Women at the Suffrage Convention 1913 50 1975 First International Women’s Day 1914 Women Making Their Mark 10 51 Margaret Mead, Anthropologist 1978 11 The Woman Sufferage Parade 1915 52 1979 Artist Louise Nevelson 1916-1917 Margaret Sanger on Trial 12 54 Philanthropist Brooke Astor 1980 13 Obstacles to Nationwide Vote 1918 55 1981 Justice Sandra Day O’Connor 1919 Suffrage Wins in House, Senate 14 56 Cosmo’s Helen Gurley Brown 1982 15 Women Gain the Right to Vote 1920 57 1984 Sally Ride and Final Frontier 1921 Birth Control Clinic Opens 16 58 Geraldine Ferraro Runs for VP 1984 17 Nellie Bly, Journalist 1922 60 Annie Oakley, Sharpshooter 1926 NOW: 20 Years Later 1928 Amelia Earhart Over Atlantic 18 Victoria Woodhull’s Legacy 1927 1986 61 Helen Keller’s New York 1932 62 Job Rights in Pregnancy Case 1987 19 1987 Facing the Subtler -

In Memoriam Newspaper Clipping, Florida Times Union

~-----===~~--~~~--~==~--------~------- EDNA L. SAFFY 1935-2010 Human rights activist founded NOW chapters She was a long-time, changed to read, "All people are a member of the Duval County Edna Saffy created equal ..." . Democratic Executive Com was a rights very active supporter of Dr. Saffy, human rights ac mittee for 35 years. In 1991, activist, women's liberation. tivist, retired college professor during the campaign for the professor and founder of NOW chapters 1992 Democratic presidential and NOW By JESSIE-LYNNE KERR in Jacksonville and Gainesville, primary, she hosted Bill Clinton The Times-Union died at her Jacksonville home at her Southside home. Active chapter Sunday 1110rning after a year in Mideast peace groups and a founder. Edna L. Saffy was such a long battle with brain cancer. member of the American Arab She died leader in the women's rights Shewas75. Institute, she later made at least Sunday. movement that she told a re Funeral arrangements are five trips to the Clinton White porter in 19~5 that she wanted pending. House, including being invited BRUCE to see the wording of the In addition to her work for LIPSKY/The Declaration of Independence women's rights, Dr. Saffy was SAFFY continues on A-7 Times-Union .. withdrawn earlier, she had Saffy only failing grades on her Continued from A·l record and no one would let her enroll. She finally found a sympathetic professor who by the president to witness the gave her a second chance. She signing of the Mid-East Peace proved him right by earning Accord in 1993. -

Race and Essentialism in Gloria Steinem

Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2009 Race and Essentialism in Gloria Steinem Frank Rudy Cooper University of Nevada, Las Vegas -- William S. Boyd School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub Part of the Law and Gender Commons, Law and Philosophy Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Cooper, Frank Rudy, "Race and Essentialism in Gloria Steinem" (2009). Scholarly Works. 1123. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/1123 This Article is brought to you by the Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law, an institutional repository administered by the Wiener-Rogers Law Library at the William S. Boyd School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Race and Essentialism in Gloria Steinem Frank Rudy Cooper* I. INTRODUCTION A. The Story of My Discovery ofAngela Harris The book that I have referred to the most since law school is Katherine Bartlett and Roseanne Kennedys' anthology FEMINIST LEGAL THEORY. 1 The reason it holds that unique place on my bookshelf is that it contains the first copy I read of Angela Harris's essay Race and Essentialism in Feminist Legal Theory.2 My edition now has at least three layers of annotations. As I reread it today, I recall my first reading. I encountered the essay in my law school feminist theory class. Up to the point where we read Harris's article, I was probably a dominance feminist, having found Catherine MacKinnon's theory that women are a group bound together by patriarchal domination to be simpatico with my undergraduate training. -

Medea of Gaza Julian Gordon Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Theater Honors Papers Theater Department 2014 Medea of Gaza Julian Gordon Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/theathp Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gordon, Julian, "Medea of Gaza" (2014). Theater Honors Papers. 3. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/theathp/3 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Theater Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theater Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. GORDON !1 ! ! Medea of Gaza ! Julian Blake Gordon Spring 2014 MEDEA OF GAZA GORDON !1 GORDON !2 Research Summary A snapshot of Medea of Gaza as of March 7, 2014 ! Since the Summer of 2013, I’ve been working on a currently untitled play inspired by the Diane Arnson Svarlien translation of Euripides’ Medea. The origin of the idea was my Theater and Culture class with Nancy Hoffman, taken in the Spring of 2013. For our midterm, we were assigned to pick a play we had read and set it in a new location. It was the morning of my 21st birthday, a Friday, and the day I was heading home for Spring Break. My birthday falls on a Saturday this year, but tomorrow marks the anniversary, I’d say. I had to catch a train around 7:30am. The only midterm I hadn’t completed was the aforementioned Theater and Culture assignment. -

Sunday, March 20, 2016 – Palm Sunday “A Truly Open Table” Santina Poor Luke 22:14-23

Sunday, March 20, 2016 – Palm Sunday “A Truly Open Table” Santina Poor Luke 22:14-23 There are times in our lives when someone seems to know the perfect thing to say just when you need to hear it the most. Maybe they share words of wisdom with you following a confusing experience. Maybe they offer words of hope and love when you are feeling sad. Maybe what they are offering are words of forgiveness after you’ve made a mistake. Or maybe they offer words of welcome, inviting you into their space and into their lives, at a time when you feel most vulnerable and alone. Throughout Luke’s gospel we are witness to many stories of Jesus offering words of wisdom, love, forgiveness, and welcome. In our text this evening, we are witness to Jesus’s invitation to his friends to join him at the table for a meal that will change their lives. It is an invitation that continues to be extended to us today to be part of this life-changing meal that takes place at a table that has room for everyone. Today I’m reading Luke’s gospel, chapter 22, verses 14-23 – Hear what the Spirit is saying to the church: When the hour came, he took his place at the table, and the apostles with him. He said to them, “I have eagerly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer; for I tell you, I will not eat it until it is fulfilled in the kingdom of God.” Then he took a cup, and after giving thanks he said, “Take this and divide it among yourselves; for I tell you that from now on I will not drink of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes.” Then he took a loaf of bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body, which is given for you. -

Imagine, Inspire, Impact

ELIZABETHTOWN COLLEGE MOMENTUM IMAGINE, INSPIRE, IMPACT STUDENT REFLECTIVE ESSAYS AUGUST 2013 Few will have the greatness to bend history itself; but each of us can work to change a small portion of events, in the total of all those acts will be written the history of this generation. Robert Francis Kennedy (1925-1968) 1 Gaining Momentum Sitting in class freshman year our minds were tuned to function on a setting which would “prepare us for college,” but how do you actually prepare for something you have only read or heard about? There is no comparison to moving into a new setting; leaving everything you worked so hard over the course of twelve years to build such as relationships and routines just to start anew. It is especially hard to imagine such a place when you are one named a first generation college student. In this case, who do you go to for all the rigorous preparations needed just to be eligible to gain admittance? It is imperative to have mentors who can help guide you through the never-ending sea of paperwork, financials, and just the basic transformation of entering the next phase of your life. So in these hard-hitting situations, where does someone such as me turn? I felt absolutely lost and overwhelmed in the beginning; like I was entering the dark depths of the unknown. When it felt like I was stranded and left to fight this battle alone, my shining light came through; my new mentors and family, Momentum. It is hard to imagine going back to that place of fear, but also in that place it was impossible to imagine that all my life’s tribulations would lead me to where I am now. -

Infertility / Loss of Life at Embryo Stage

M. E. N. D. Mommies Enduring Neonatal Death Infertility/Loss of Life at Embryo Stage A new year has begun. Many of you might sadly sigh time, I think many people had already forgotten about our and say, "another year…," meaning another year has passed little one, who should have been 4 or 5 months old. I felt it without the joy and hope of a baby. Perhaps some of you was too late to really explain to anyone other than my were so sure 2014 was YOUR year, THE year. And now it's husband why I was in such a funk. He got it and was sad gone and 2015 is underway. along with me. However, I felt no one else would Though I cannot completely relate to infertility in the understand, because not only had it been a full year since the traditional sense of the word, I am considered to have miscarriage, I was only 10 weeks along when I lost the baby. secondary infertility since the last two of my three Byron and I saw our little one's beating heart and developing pregnancies ended early with a loss. I never had trouble body through sonogram images, but no one else did. Unless conceiving, just keeping my babies. Jonathan was stillborn one is educated on embryonic development, I'm sure most due to a cord accident at 29.5 weeks, and Baby Mitchell was assumed we lost "a blob." No, the last time we saw it alive, miscarried at 10 weeks, likely due to a partial molar it was a tiny person with a beating heart, a round head, a pregnancy (my own unofficial diagnosis). -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Fairy Tales

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Fairy Tales for Adults: Imagination, Literary Autonomy, and Modern Chinese Martial Arts Fiction, 1895-1945 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures by Lujing Ma Eisenman 2016 © Copyright by Lujing Ma Eisenman 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Fairy Tales for Adults: Imagination, Literary Autonomy, and Modern Chinese Martial Arts Fiction, 1895-1945 By Lujing Ma Eisenman Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Languages and Cultures University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Theodore D Huters, Chair This dissertation examines the emergence and development of modern Chinese martial arts fiction during the first half of the twentieth century and argues for the literary autonomy it manifested. It engages in the studies of modern Chinese literature and culture from three perspectives. First, approaching martial arts fiction as a literary subgenre, it partakes in the genre studies of martial arts fiction and through investigating major writers and their works explains how the genre was written, received, reflected, and innovated during the period in question. Second, positioning martial arts fiction as one of the most well received literary subgenre in the modern Chinese literary field, it discusses the “great divide” between “pure” and “popular” literatures and the question of how to evaluate popular literature in modern China. Through a series of textual analysis contextualized in the lineage of martial arts fiction, it offers insight into ii how the ideals of so-called “pure” and “popular” literatures were interwoven in the process of reviewing and re-creating the genre. -

Signatories to the Letter to Presidents Obama and Karzai in Support of Afghan Women’S Rights

Signatories to the Letter to Presidents Obama and Karzai in Support of Afghan Women’s Rights Madeleine K. Albright Sima Samar Meryl Streep Former U.S. Secretary of State Chairperson, Afghanistan Independent Actress and Human Rights (1997-2001) Human Rights Commission Activist Mary Akrami Samira Hamidi Sandra Day O’Connor Mahbouba Seraj Executive Director Afghanistan Country Director Retired U.S. Supreme Court Director Afghan Women Skills Afghan Women’s Network Justice (1981-2005) Organization for Research for Development Center Peace & Solidarity Yasmeen Hassan Nasima Omari Hangama Anwari Global Director Executive Director Hassina Sherjan Executive Director Equality Now Women’s Capacity Building Founder and CEO Women and Children Legal and Development Aid Afghanistan for Education Research Foundation Khaled Hosseini Organization Author Mina Sherzoy Judge Najla Ayubi Founder, Khaled Hosseini Yoko Ono Founder Country Director Foundation Artist and Human Rights World Organization for Mutual Open Society Afghanistan Activist Afghan Network Shinkai Karokhail Afifa Azim Parliamentarian Arezo Qanih Eleanor Smeal Director and Cofounder National Assembly of Program Director President Afghan Women’s Network Afghanistan Education Training Center for Feminist Majority Foundation Poor Women and Girls of Ruqia Azizi Zalmay Khalilzad Afghanistan Gloria Steinem Deputy Managing Director Former U.S. Permanent Feminist Journalist Organization of Human Representative to the United Zohra Rasekh Welfare Nations, Former U.S. Vice President Sir Patrick Stewart Ambassador to Iraq, Former Committee on the Elimination Actor and Human Rights Joan Baez U.S. Ambassador to of Discrimination Against Activist Artist and Human Rights Afghanistan Women Activist Sting Stephen King Humaira Rasuli Artist and Human Rights William S. Cohen Author Executive Director Activist Former U.S.